In Partnership With

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

Background

Since 2013, mounting evidence has pointed to serious human rights violations committed against civilians by the Egyptian military. during its campaign against ISIS-affiliated militants in the North Sinai region. These violations include extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial detention.

The Sinai Foundation for Human Rights (SFHR) obtained testimonies from two members of a local militia allied with the Egyptian military in its war against ISIS, revealing the existence of mass graves in two separate locations in North Sinai.

According to their accounts, the Egyptian military used these sites to bury the bodies of detainees held in unofficial detention facilities between 2016–2019. They described how groups of blindfolded, handcuffed, detainees were taken out, executed in field operations, and buried in these locations.

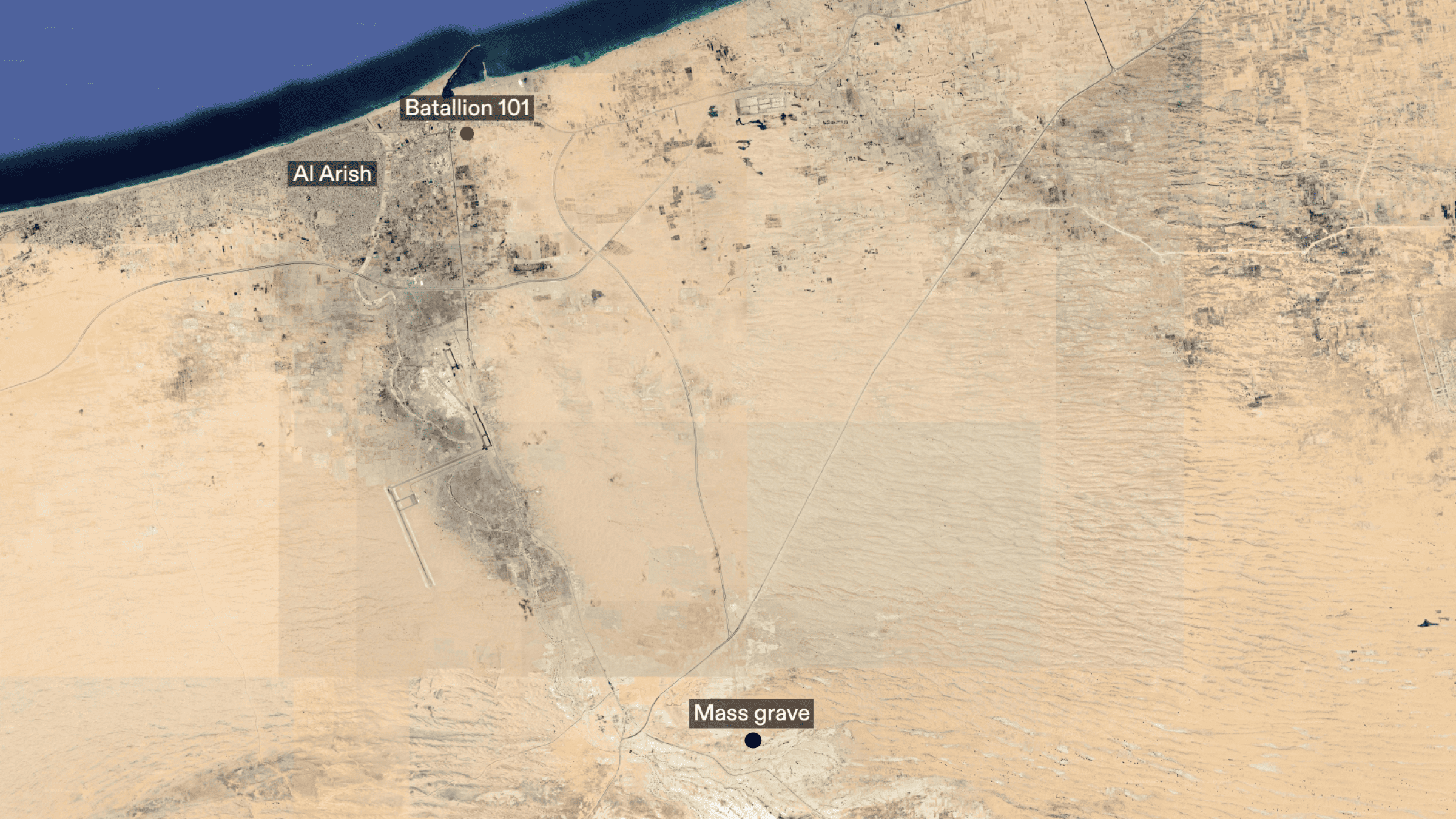

SFHR’s team located one of these mass graves approximately 20km from a site known as Battalion 101. Battalion 101, in the city of Al-Arish, was the central command headquarters for Egyptian military operations against ISIS in the region and an unofficial detention site used by the same military. SFHR has collected dozens of testimonies from former detainees who endured severe torture at Battalion 101. Many of them reported that detainees were taken away under the pretence of being released, only to never return home.

SFHR conducted two site visits to the mass grave site and its surroundings. During these visits, they documented the presence of numerous human remains and collected evidence to support further investigation.

SFHR’s full report is available here.

The Mass Grave Site

Forensic Architecture (FA) conducted research into the identified mass grave site to establish a timeline of its use and investigate potential patterns of military presence.

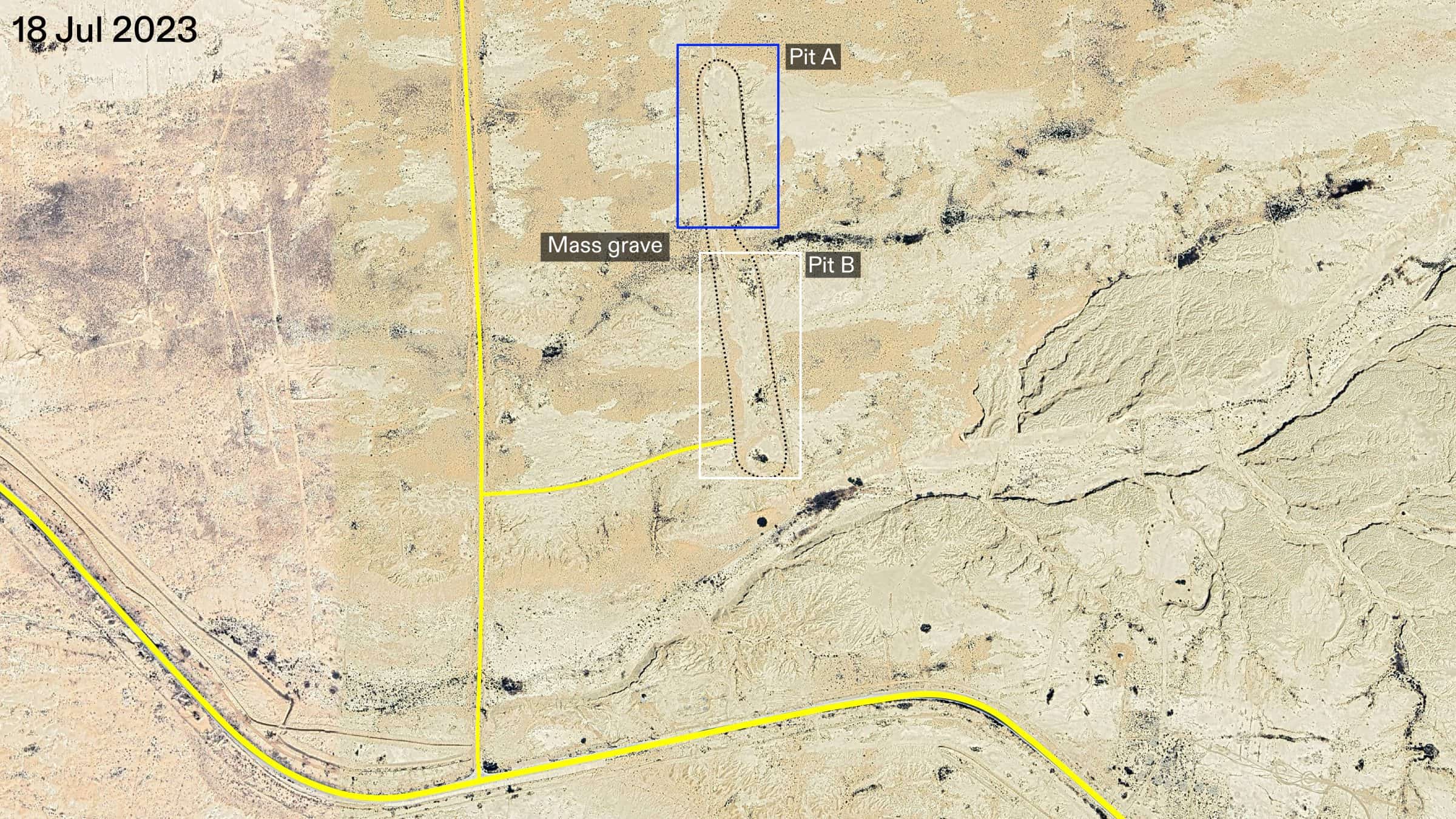

The mass grave site identified by SFHR is approximately 20km south of Al-Arish, and less than 1km from the Abu Aweigila–Al-Arish highway. It consists of two large, connected pits: Pit A and B.

During site visits in December 2023 and January 2024, SFHR researchers recorded media evidence confirming the presence of bodies in Pit A, and observed the presence of human remains in Pit B.

Findings

We analysed high-resolution satellite imagery of the mass grave site and its surrounding areas. By comparing imagery over time, we identified indicators of military presence, such as outposts, vehicles, tire tracks, and ground disturbances.

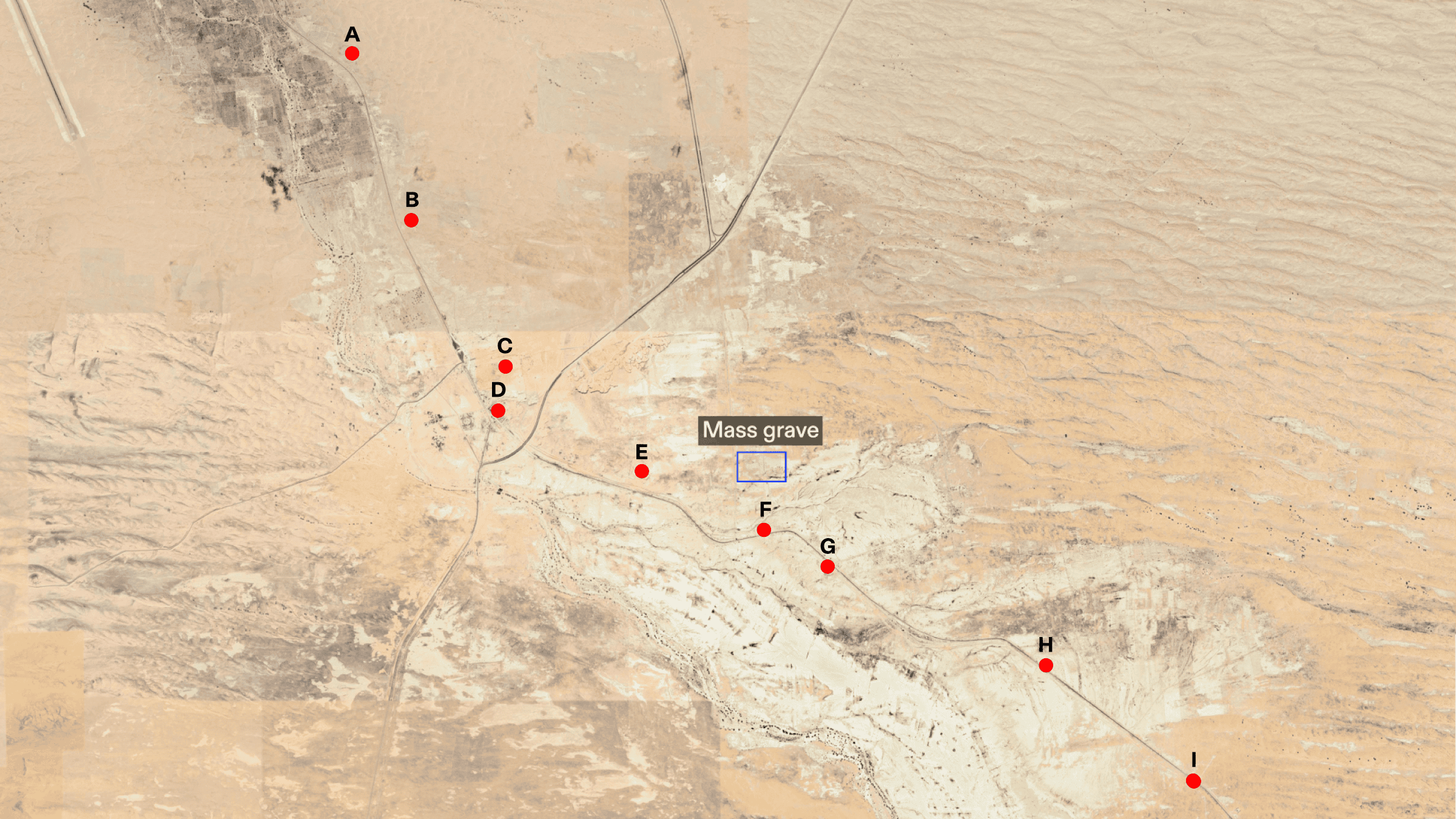

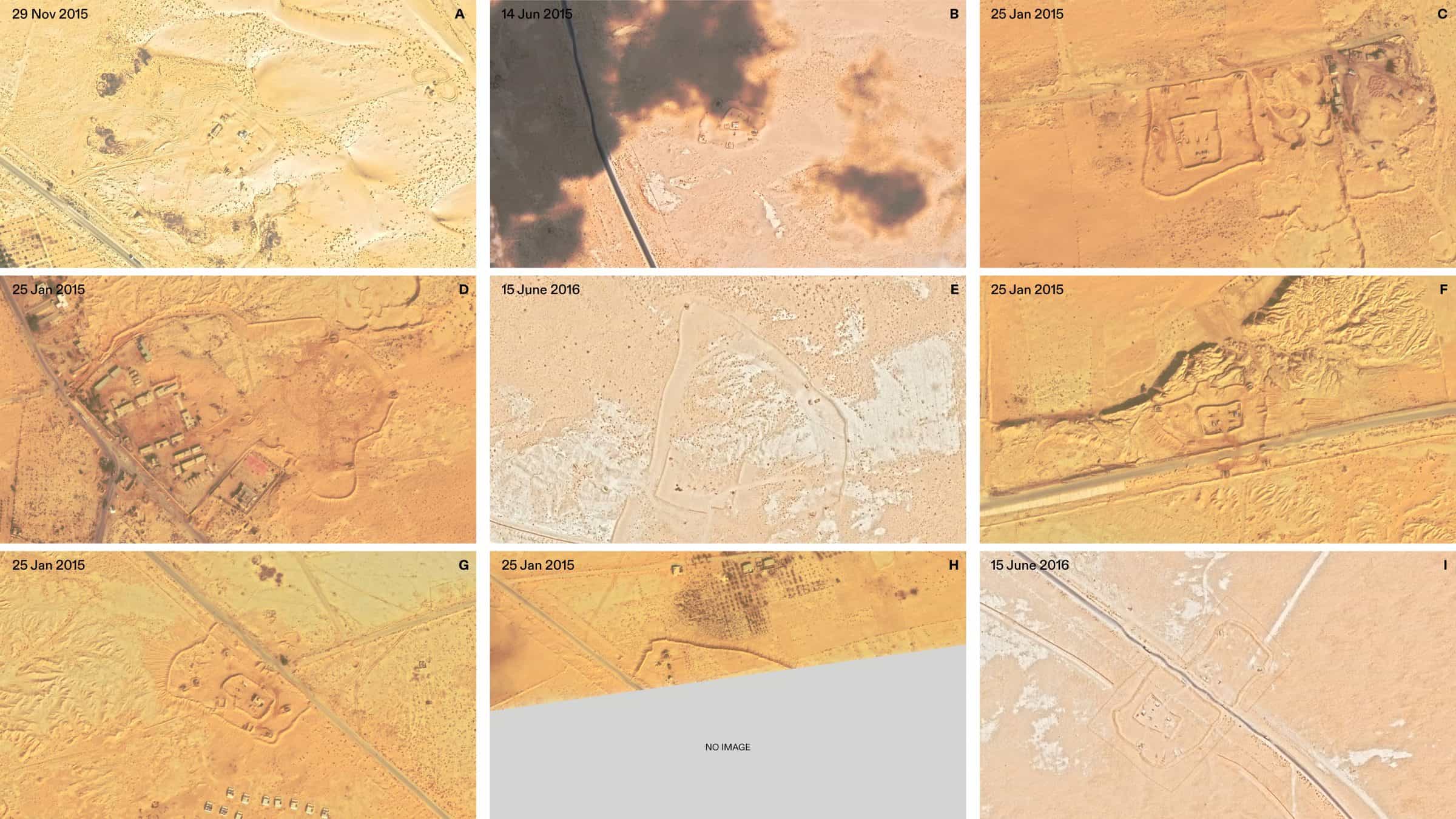

Satellite imagery analysis indicates significant militarisation in the vicinity of the mass grave between 2013–2016 (see p. 7 of our report). Within an 8km radius of the site, nine military outposts were identified along the Abu Aweigila–Al-Arish highway, the closest located less than 1km from the mass grave. These outposts form an integrated network connected by sand trenches and other earthworks; a practice commonly used to conceal movement and facilitate military operations. Satellite imagery also reveals sand barriers along the road east of the mass grave, typically employed to control vehicle movement and block road access.

In addition, satellite imagery from 2013–2020 shows widespread destruction of buildings, including civilian infrastructure, indicative of forced civilian displacement in the region (see p. 12 of our report).

Between 2010–2023, we documented several periods of ground activity in and around both pits. Prior to 2015, the activity at the site was minimal. The most significant activity, marked by multiple tracks directly within the pits, took place between January 2015–June 2017. The timing of this activity coincides with the 2015–2017 peak of armed clashes in Sinai and a broader escalation of the conflict (see p. 14 of our report).

We analysed the size of tire tracks documented in and around the site (see p. 28 of our report). We observed that the tracks are consistent in size with those produced by a Humvee M1151, Cougar 6×6 MRAP, Toyota Hilux, or Toyota Land Cruiser—all military vehicles known to have been deployed during the conflict.

Using images collected by SFHR researchers during their visits, we digitally reconstructed Pit A in 3D and mapped the locations of bodies visible in the media captured on site (see p. 33 of our report).

Our analysis shows that human remains were buried in shallow earth and widely dispersed across Pit A. We identified at least 36 skulls, indicating that at least this number of individuals were buried in Pit A. However, SFHR reports suggest that the actual number of bodies may be significantly higher, with numerous remains unaccounted for in both pits.

While bone displacement can be caused by environmental forces over time, the widespread distribution of remains across the site suggests that the burials occurred at multiple points in time, rather than as part of a single event.

Conclusion

The periodic presence of tire tracks, as well as the evident militarisation of the area around the mass grave site, suggests that repeated visits to the site occurred between 2015–2023, likely by military or military-affiliated vehicles.

The emergence of a constellation of military outposts and the clearing of civilian infrastructure beginning in 2013 indicate tight control over the area by the Egyptian military. This control, coupled with the imposition of strict military curfews starting in 2014, makes it unlikely that any non-military actors could have accessed the site regularly, let alone bury bodies, without being observed or challenged.

Taken together, the above documentation suggests that the Egyptian military is not only aware of the presence of human remains on the site but is likely responsible for the presence of those remains.