Throughout history, orangutans have inhabited the threshold between humankind and nature. In the Malay language, the name means ‘people [orang] of the forest [hutan]’).

In the eighteenth century, the supposed proximity between man and orangutan was predicated on their mere physical resemblance to humans. Today, neurological, genetic, social, and linguistic similarities are at the frontiers of debates regarding the future of laws and rights pertaining to the great apes.

Are apes objects or subjects of law? Should the killing of orangutans be considered as murder?

In October 2016, expanding upon our original project on Ecocide for an exhibition at the Istanbul Design Biennale, three ‘limit conditions’ are explored into relation with one another: the threshold of the human species; the threshold of the forest; and the threshold of the law. What can we accept as a ‘human being’? How does this question interact with shifting environmental thresholds, and the political limits of territory and sovereignty?

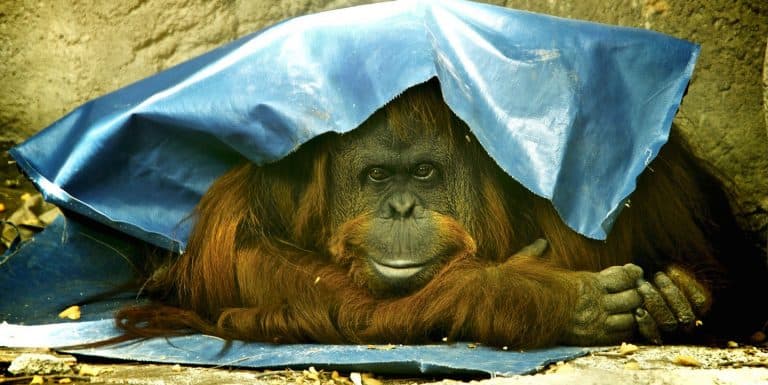

Sandra

In 2014, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, a 30-year-old German-born orangutan won a legal status that approximated ‘human rights’.

The following year, the orangutan, Sandra, was formally declared a ‘non-human person’ by an Argentine court, following legal proceedings brought by the Association of Professional Lawyers for Animal Rights (AFADA).

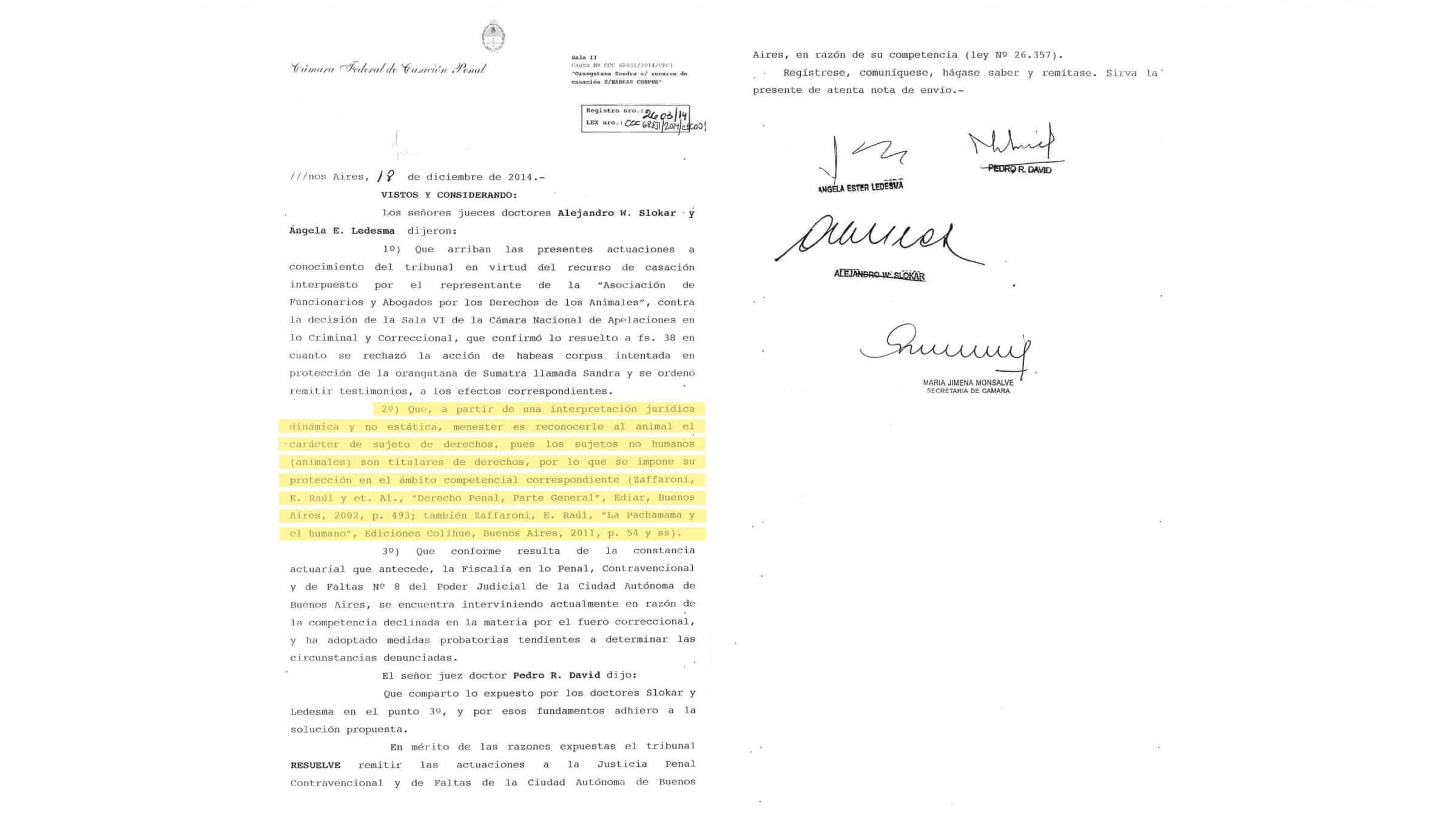

The organisation had applied for a ‘habeas corpus’ writ, on Sandra’s behalf. Habeas corpus, a right originating in seventeenth century England, demands a person’s release unless lawful grounds are shown for their detention. In the second half of the twentieth century, habeas corpus became associated with demands to produce the bodies of the many people ‘disappeared’ in South America’s dirty wars, and the West’s ‘war on terror’.

Trial

The Sandra Trial involved, on all sides, expert witnesses on animal and primates cognition from Argentina and elsewhere. Three positions aroused. The city (which owns the Zoo) considered Sandra as an object and regarded her as its property.

The petitioners have adopted an abolitionist perspective and asked for her to be considered a subject of law, demanding her immediate release. The compromise position saw it as a matter of welfare, seeking not rights but the improvement her conditions of life and her relocation into an ape sanctuary. The threshold between humans and animals was determined not only scientifically and juridically, but rather politically and culturally.

AFADA’s habeas corpus argument on Sandra’s behalf described the ‘unjustified confinement of an animal with proved cognitive capacity’. The court ultimately agreed, ruling that Sandra was a sentient being, with thoughts and feelings, and that she had been wrongfully deprived of her freedom at Buenos Aires zoo.

In the eyes of the law, Sandra became subject, rather than object.

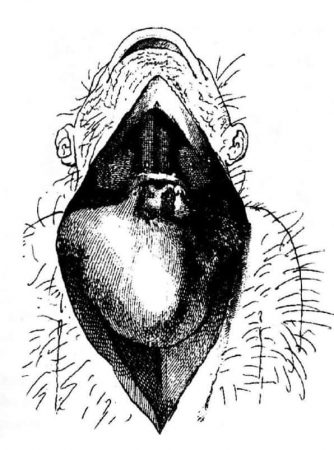

Vocal Culture

In 1777, the Dutch anatomist Petrus Camper dissected an orangutan corpse, searching the answer to a mystery: was the orangutan a kind of human, or was it an animal? From the perspective of eighteenth century medical science, the answer lay in the voice—thought to be the dwelling place of language.

After dissecting the ape’s throat, Camper proclaimed that since the orangutan’s larynx was physiologically unable to produce anything resembling human vocal speech, the orangutan could never be human. The threshold between man and animal, previously a blurry frontier, had become clear, and rigid.

The Threshold of the Human

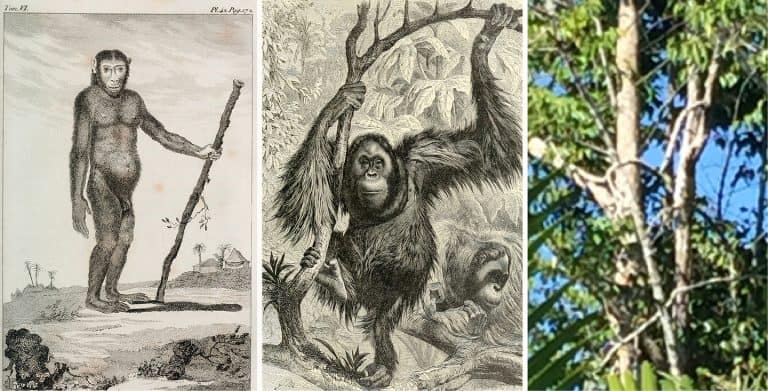

When European travellers, scientists, theologians and traders first encountered great apes, they perceived them to be “intermediate animals” inhabiting (as Donna Haraway explained in “Primate Vision”) the murky border between animals and humans, nature and culture.

In a long footnote to this book Jean Jacques Rousseau turns his attention to the orangutan. Rousseau’s orangutans perform all the things 17th and 18th centuries scholars believed apes to perform, enjoying fire, cooking and burying their dead. The humanity of orangutans was crucially manifested in architecture of the nests they build in the forest. Rousseau thought that the ape shared with humans the capacity to learn, improve and perfect itself, the first slip in a slippery slope towards civilization. But he conceived of the threshold of the human to be elastic: once you can “become human” you could also “become animal” and then slide back across the border again.

Buffon’s orangutan is human-like, standing upright against the backdrop of deforested land. The stick he is holding in his hand has still some live leaves on it. It is a branch recently cut from a tree, the ape has just left the forest and entered the agrarian domain of the fields, that is the area of law and economy. This image supports the 18th century conception that the orangutan is part of the human specie. This opened up a series of ethical issues? If the orangutan is human is the human specie stratified? Could this be used as a justification of slavery?

In the end of the 18th century, scientific research has “dehumanized” the orangutan. In this 19th century depiction, one detail significantly changed: the orangutan still holds a branch in its hand, it is of similar diameter to the one in the previous image. However, this branch is still connected to a tree, the orangutan is back from the field to the forest, it is part of nature—an animal.

Scientists consider these treetops structures to be not only the result of instinctive behaviour (like bird nests or a termite hills) but as transferable “cultural artefact” with variations across different communities. The architecture of this nest demonstrates an important synthesis confirmed by architecture: the branches (of a similar thickness to the previous two) are tools, but they are still connected to the tree. The ape has fractured, bent and tied them together to form the basic structure of a nest.

The Architecture of the Nest

Orangutans build nests in the treetops every evening and abandon them every morning. They shift daily from architecture to archeology. After a few days they can be distinguished by their brown foliage. Primatologists seek to spot them in order to estimate population sizes, or number of apes lost.

Orangutan Skull

That these remains of an orangutan were found in a shallow grave suggests an attempt to hide its killing. It is thus the strongest testimony that the perpetrators have themselves understood it to be a crime. The GIS reader (held by the hand of another humanoid) locates the grave in absolute terms in relation to the planet. Closing the exhibition, this image thus suggests a different conception of the universal: rather than seek for apes to be protected by individual form of (almost) human rights we could ask for the extension of a certain kind of collective, environmental orangutan rights’ to humans and with it a certain “becoming humanoid” of humanity.