Date of Incident

Location

Publication Date

Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

- Cloud Studies at Tensta Konsthall

- Cloud Studies at the Whitworth

- Slow Boil

- Cloud Studies at UTS Gallery

- Forensic Justice

- Error: The Art of Imperfection

- Are We Human?

- Clouds⇄Forests

- Forensic Architecture: Hacia una Estética Investigativa

- Forensic Architecture: Towards an Investigative Aesthetics

- Ape Law at Istanbul Design Biennial 2016

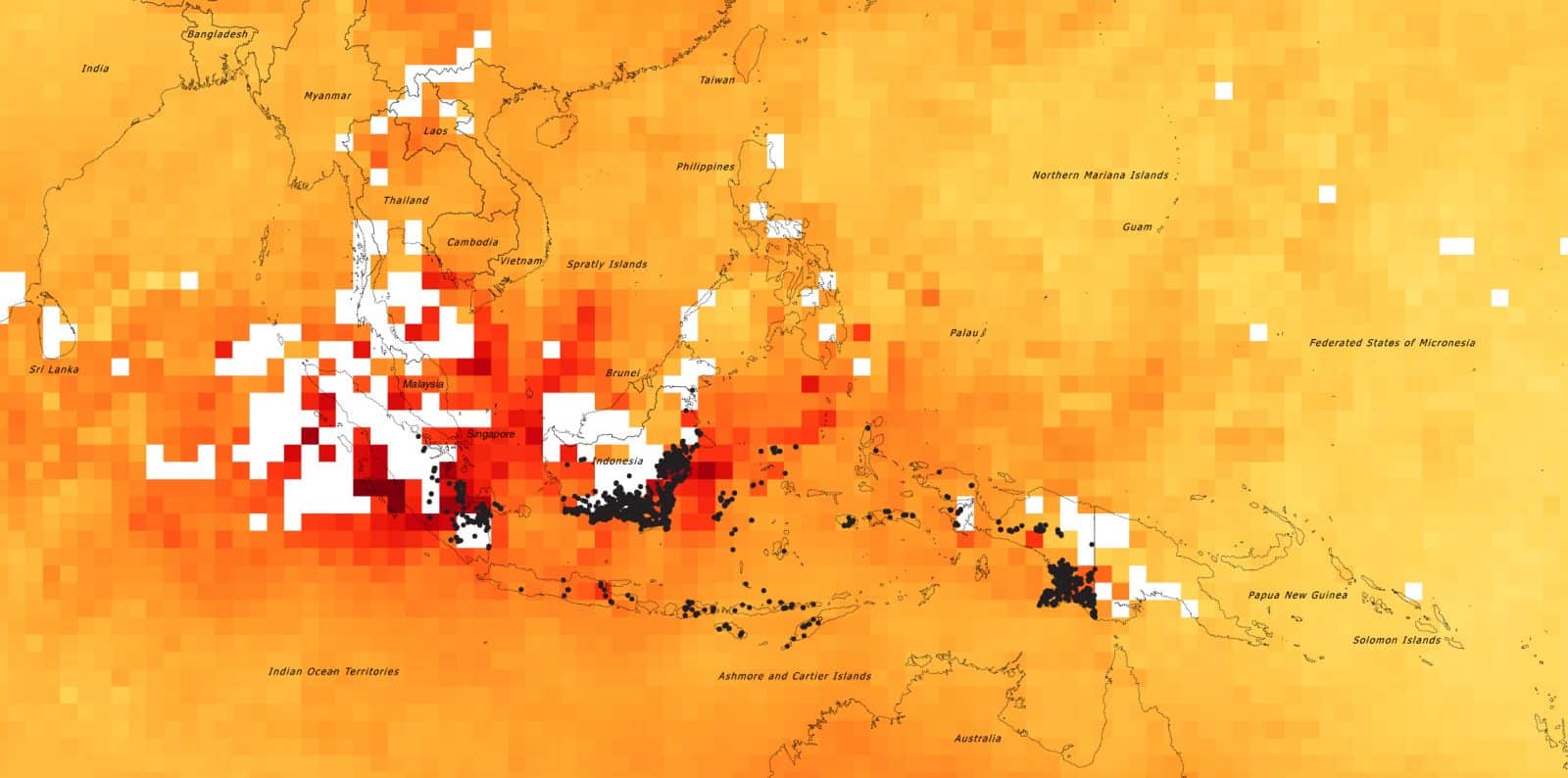

In 2015, fires in the Indonesian territories of Kalimantan and Sumatra consumed over twenty-one thousand square kilometres of forest and peat lands. A cloud formed that contained more carbon, methane, ammonium and cyanide than the entire annual emissions of the German, British or Japanese industry.

As the acrid cloud drifted north and westwards, it engulfed a zone that extended from Indonesia across Malaysia and Singapore to southern Thailand and Vietnam. Scientists estimate that this resulted in more than a hundred thousand premature deaths, and that the fires might push the world beyond 2ºC of global warming, into the realm of potential and unpredictable calamities, faster than expected.

Human rights lawyer Baltasar Garzón, through his organisation, Fundación Internacional Baltasar Garzón (FIBGAR), commissioned Forensic Architecture (FA) to gather evidence regarding the causes and consequences of the fires, toward the aim of an international trial.

We understood the vast ‘carbon cloud’ as a harbinger of a new international crime of ecocide—one that will only become more relevant in the years to come.

“Ecocide is the extensive damage to, destruction of or loss of ecosystem(s) of a given territory, whether by human agency or by other causes, to such an extent that peaceful enjoyment by the inhabitants of that territory has been or will be severely diminished.”

– Polly Higgins’ proposal for the Rome Statute

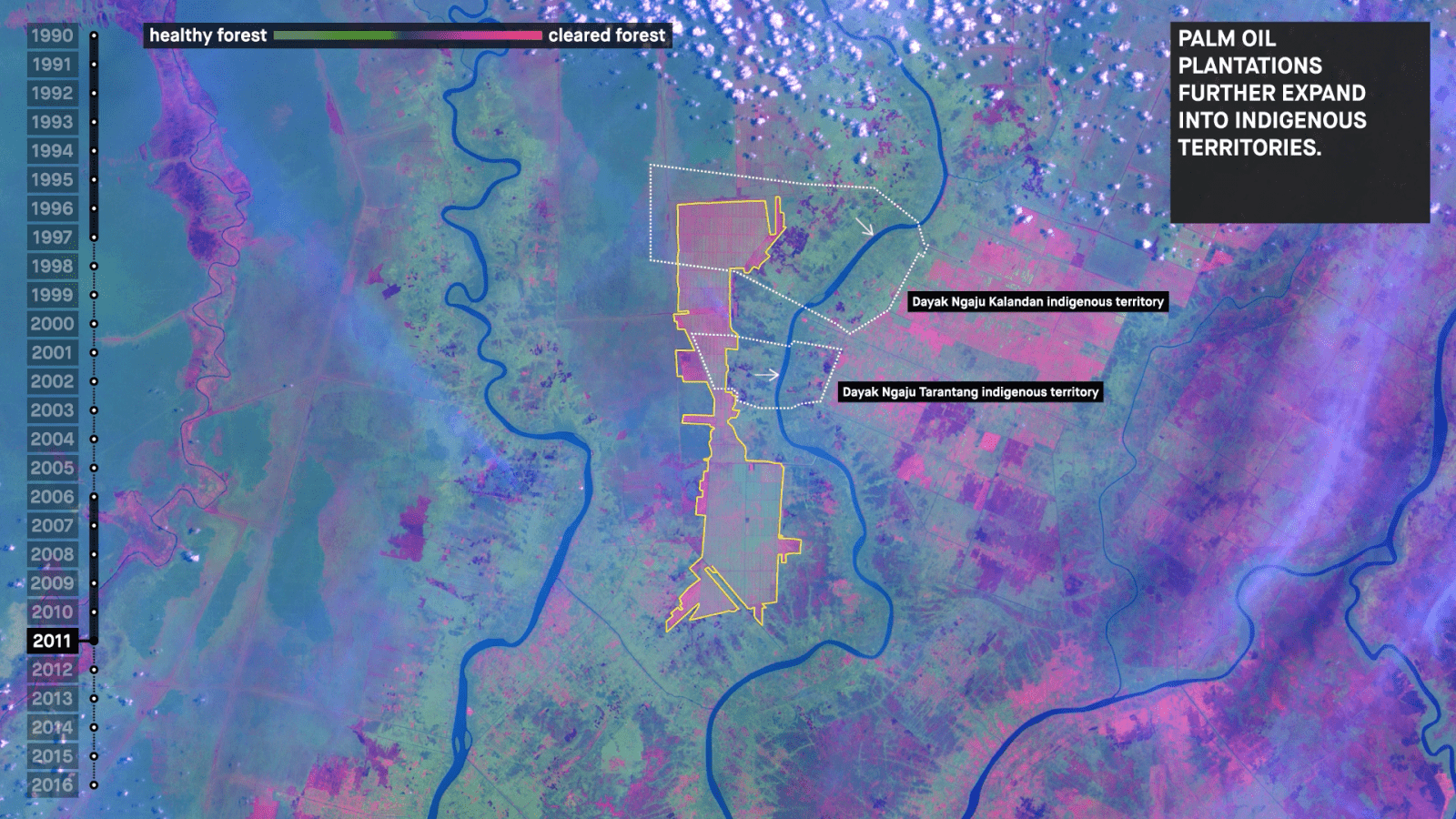

Some of the roots of the 2015 fires can be traced back to repressive policies of the Indonesian government in the second half of the twentieth century, when local and international companies collaborated with the Indonesian armed forces to appropriate vast tracts of land from indigenous populations, and then employed those same populations in exploitative conditions.

The fires took place mainly in dried peat lands, made up of thousand-year-old decomposed organic matter. In their undisturbed state, peat lands are fire-resistant, but decades of canal digging by large agri-business operators, draining and drying the peat to prepare it for the monoculture plantation of palm oil, left it highly flammable. Peat can smoulder underground for weeks, and that smouldering heat can ‘creep’ many kilometres from the original source of the fire.

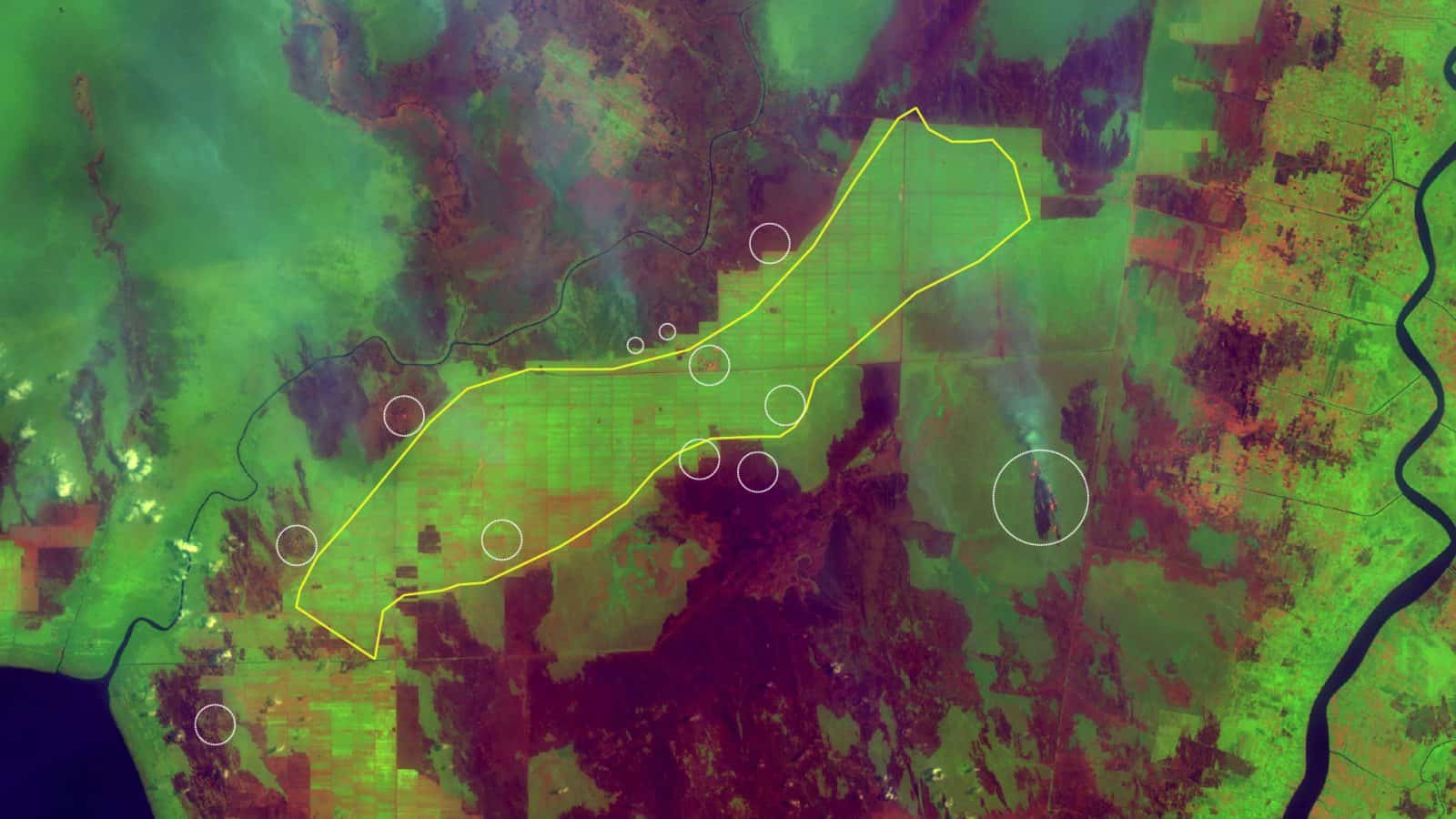

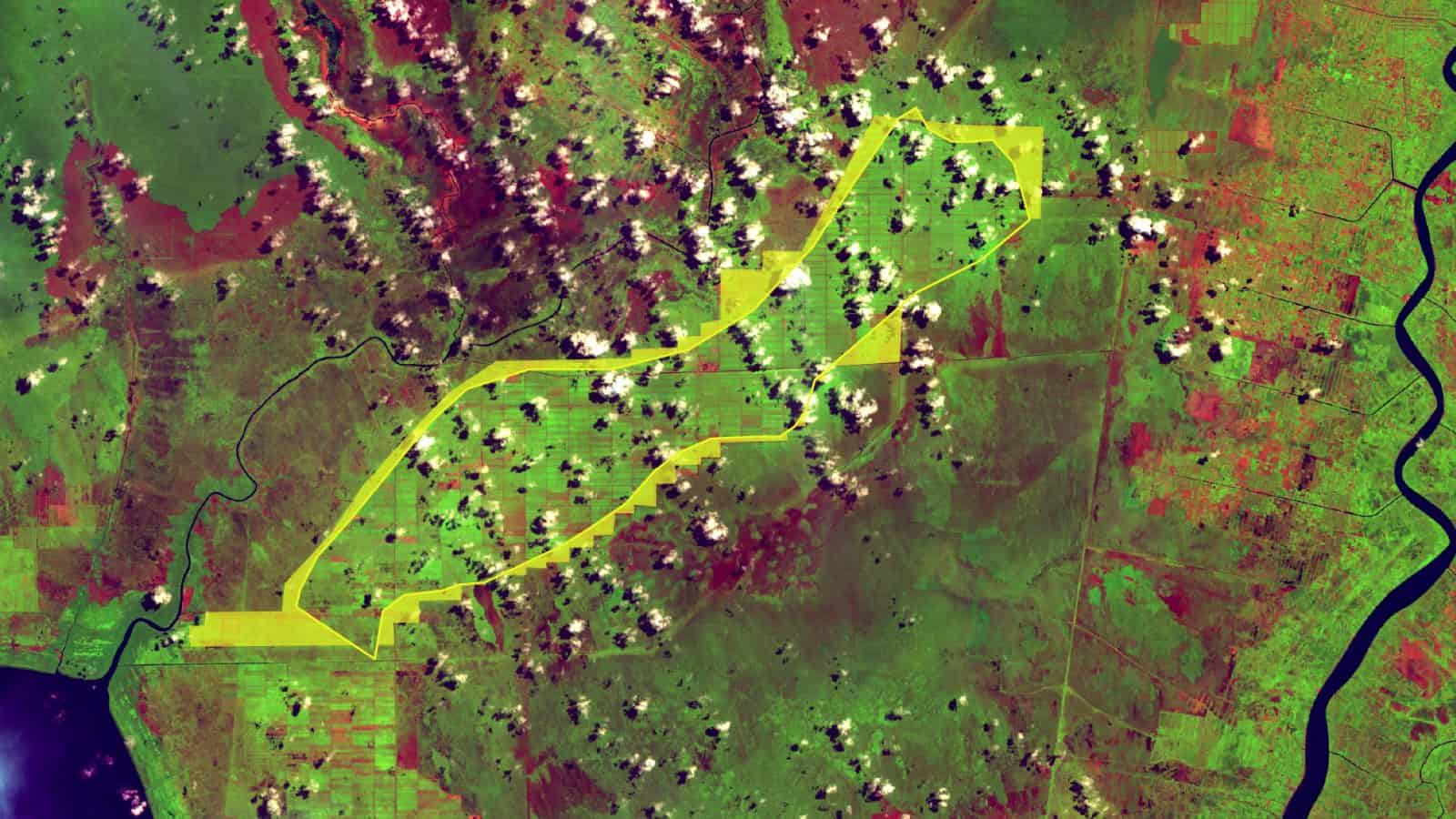

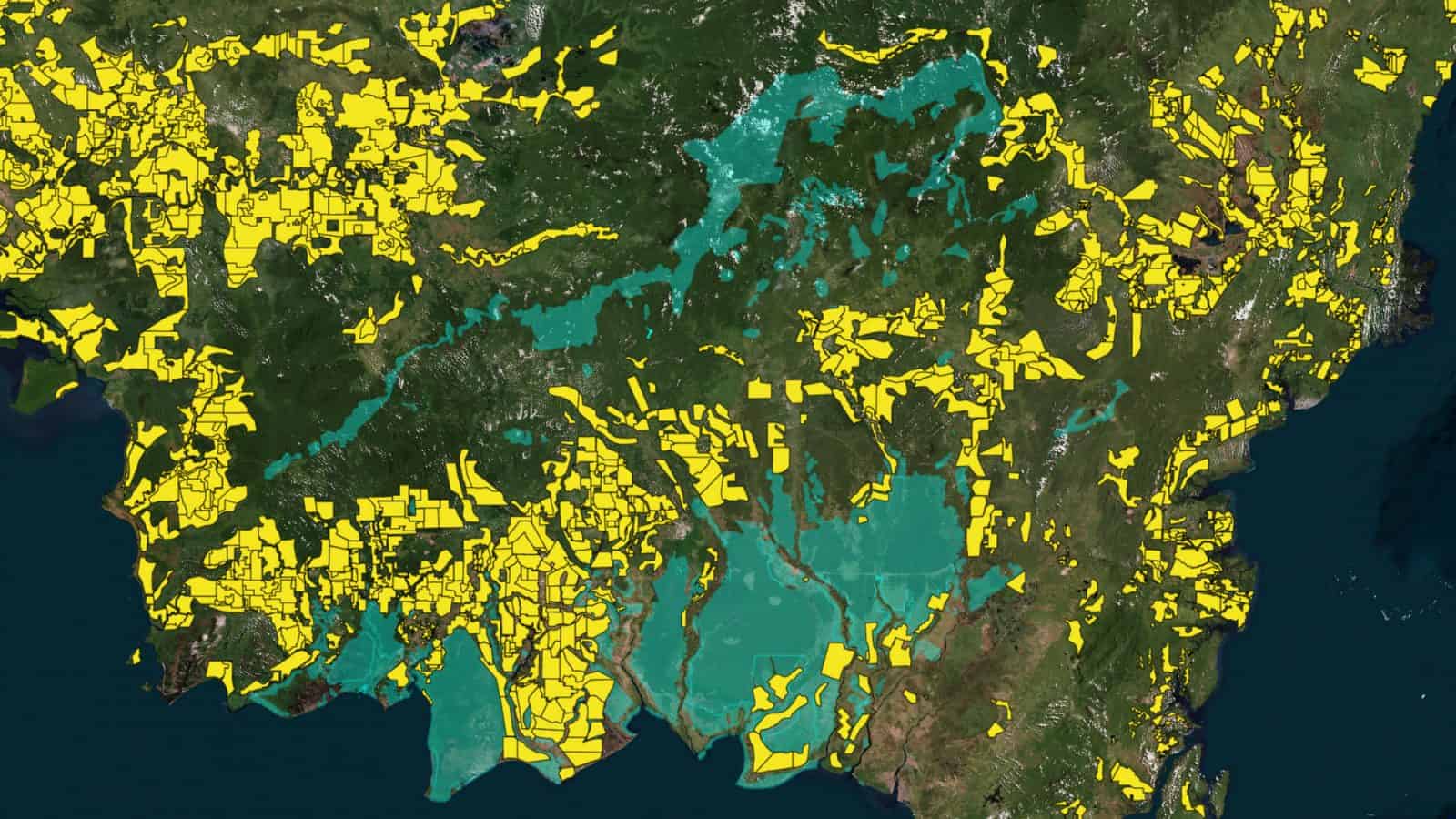

The sources of fires in 2015, began from both within and outside the plantations, some crossing the concession borders. As a result, the cleared land was not confined within the boundaries if the concession site. In the case of a concession belonging to the Best Agro Group, the boundary of the plantation had expanded by %30 into the national forests, within less than a year from the 2015 burnings (marked in yellow).

The borders of many of the palm oil concessions in Kalimantan are shared with the border of mauritoriums, inhabited by various forms of life. As the borders are further pushed and pulled with the intentional use of fires, the livelihood of many of such species will be endangered. On of the key casualties of the Indonesian fires is the Orang-utan which translates as the man of the forests.

On June 24th, 3023, Greenpeace and Friends of National Parks Foundation (FNPF) discovered this orang-utan skull buried near the borders of two palm oil plantations (run by subsidiaries of Eagle High/BW Group and Bumitama Agri Group) near Tanjung Putting National Park in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.

That these remains of an orang-utan were found in a shallow grave suggests an attempt to hide its killing. It is thus the strongest testimony that the perpetrators have themselves understood it to be a crime. The GIS reader (held by the hand of another humanoid) locates the grave in absolute terms in relation to the planet. This image suggests a different conception of the universal: rather than seek for apes to be protected by individual form of (almost) human rights we could ask for the extension of a certain kind of collective, environmental “orang-utan rights” to humans and with it a certain “becoming humanoid” of humanity.

Update

22.10.2016

22.10.2016

Throughout history, orang-utans have inhabited the threshold between humankind and nature. In the Malay language, the name means ‘people [orang] of the forest [hutan]’).

In the eighteenth century, the supposed proximity between man and orang-utan was predicated on their mere physical resemblance to humans. Today, neurological, genetic, social, and linguistic similarities are at the frontiers of debates regarding the future of laws and rights pertaining to the great apes.

Are apes objects or subjects of law? Should the killing of orang-utans be considered as murder?

In October 2016, expanding upon our original project on Ecocide for an exhibition at the Istanbul Design Biennale, three ‘limit conditions’ are explored into relation with one another: the threshold of the human species; the threshold of the forest; and the threshold of the law. What can we accept as a ‘human being’? How does this question interact with shifting environmental thresholds, and the political limits of territory and sovereignty?

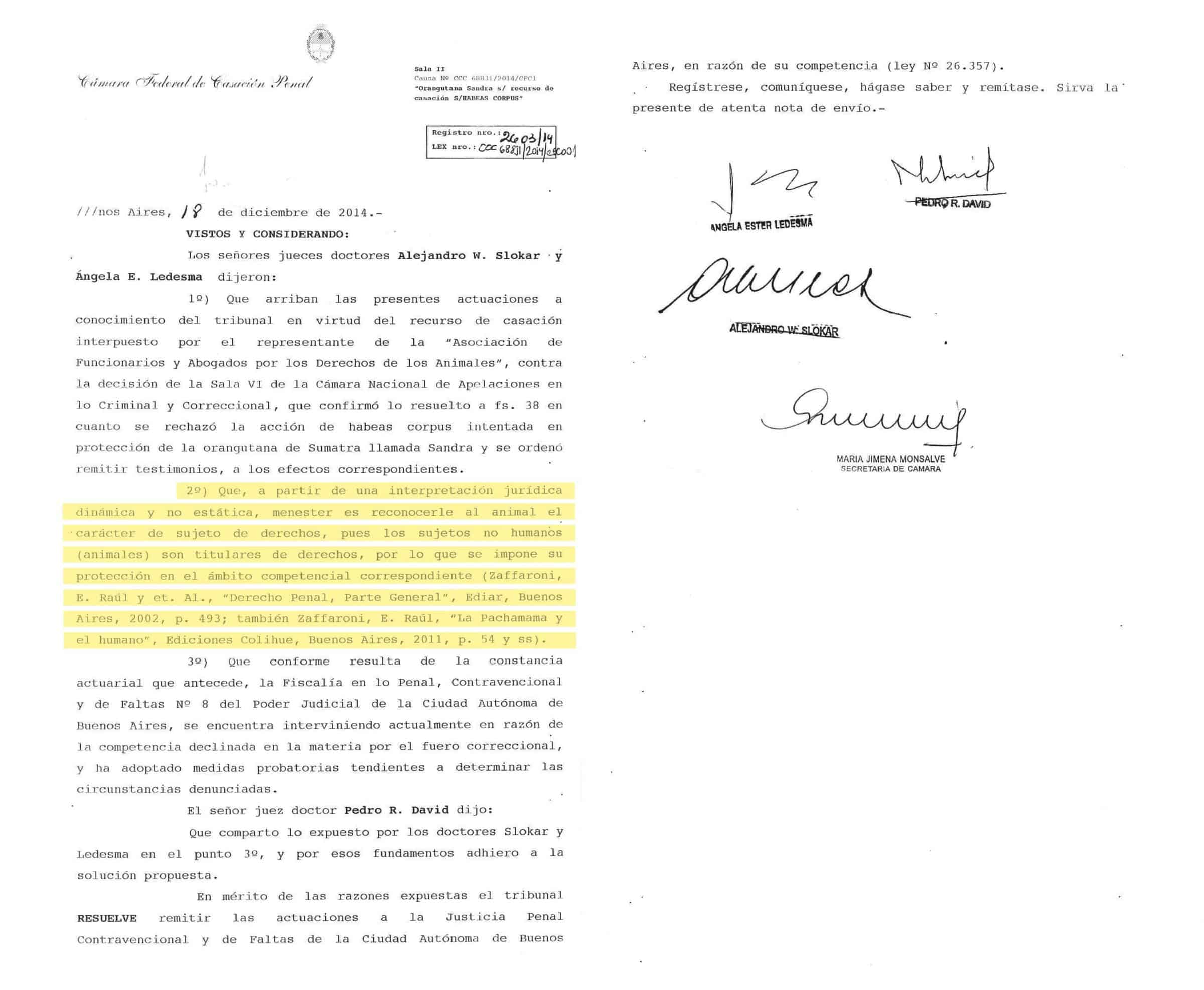

In 2014, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, a 30-year-old German-born orang-utan won a legal status that approximated ‘human rights’.

The following year, the orang-utan, Sandra, was formally declared a ‘non-human person’ by an Argentine court, following legal proceedings brought by the Association of Professional Lawyers for Animal Rights (AFADA).

The organisation had applied for a ‘habeas corpus’ writ, on Sandra’s behalf. Habeas corpus, a right originating in seventeenth century England, demands a person’s release unless lawful grounds are shown for their detention. In the second half of the twentieth century, habeas corpus became associated with demands to produce the bodies of the many people ‘disappeared’ in South America’s dirty wars, and the West’s ‘war on terror’.

AFADA’s habeas corpus argument on Sandra’s behalf described the ‘unjustified confinement of an animal with proved cognitive capacity’. The court ultimately agreed, ruling that Sandra was a sentient being, with thoughts and feelings, and that she had been wrongfully deprived of her freedom at Buenos Aires zoo.

In the eyes of the law, Sandra became subject, rather than object.

Methodology

Methodology

Archives and mapping

The report includes GIS mapping of data compiled from the database of environmental advocacy NGOs in Indonesia. For example detailed maps of sources of fire throughout the year of 2015, legal land classifications in Central Kalimantan in 2015, coordinates and shapes of all oil plantation blocks in 2005 and 2015, and their legal status, as well as details of two court reports were gathered from WALHI Central Kalimantan (The Indonesian Forum for Environment).

Details of Orangutan casualties, including drone footage of ape graves, x-ray documents and GPS coordinates of ape graves were collected from Indonesia’s Centre for Orangutan Protection (COP). Satellite documentation was gathered from the Landsat archives of NASA Earth Observatory.

Fieldwork

The investigation relies upon information gathered during two periods of field work in Indonesia, undertaken in June 2016 and January 2017. During those periods, sites severely affected by the 2015 fires were mapped and studied, using data from local collaborators and remote sensing.

These studies were undertaken with the support of Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI), the largest and oldest environmental advocacy NGO in Indonesia, as well as the COP.

Remote sensing analysis

The report uses two methodologies to interpret the satellite images. First technique is named Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR) and uses near-infrared (NIR) and shortwave-infrared (SWIR) wavelengths to highlight burn areas in a landscape and estimate fire severity. The Second technique deployed in the report is named Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and assess the levels of photosynthetic activity of plants and allows the identification of changes in land cover over time.

Our analysis used satellite images from the NASA Landsat from Aug 1997, Aug 2005 and Aug 2015 which bracketed the period of the most extreme manifestation of land appropriation and environmental violence in the region. The resolution of these images – a pixel is 30 and 60 meters square respectively – is not sharp enough to capture individual houses or even villages, but sufficient to record territorial scale burnings and vegetation change.