Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Collaborators

- ODHAG – Oficina de Derechos Huamanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala (Raul Najera and Ana Carolina)

- Guatemala Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG)

- CALDH – Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos

- SITU Research

Methodologies

Forums

Between 1960 and 1996, Guatemala was consumed by conflict between an increasingly militarised state and a widespread rural insurgency. The state’s counterinsurgency efforts peaked from the late 1970s, as security forces pursued the guerrillas into the country’s highlands.

According to a 1999 report by Guatemala’s Historical Clarification Commission (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico; CEH), a UN-backed body established toward the end of the conflict, more than 200,000 people were killed or disappeared during more than three decades of violence. The CEH attributed 97% of the human rights violations it documented to state security forces.

Forensic Architecture (FA) was commissioned by a Guatemalan NGO, the Centro para la Acción Legal en Derechos Humanos (CALDH), to support their efforts to gather evidence for the trial of the country’s former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt, whose brief military regime ran from March 1982 to August 1983, and senior members of his security apparatus.

Montt would ultimately be convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity.

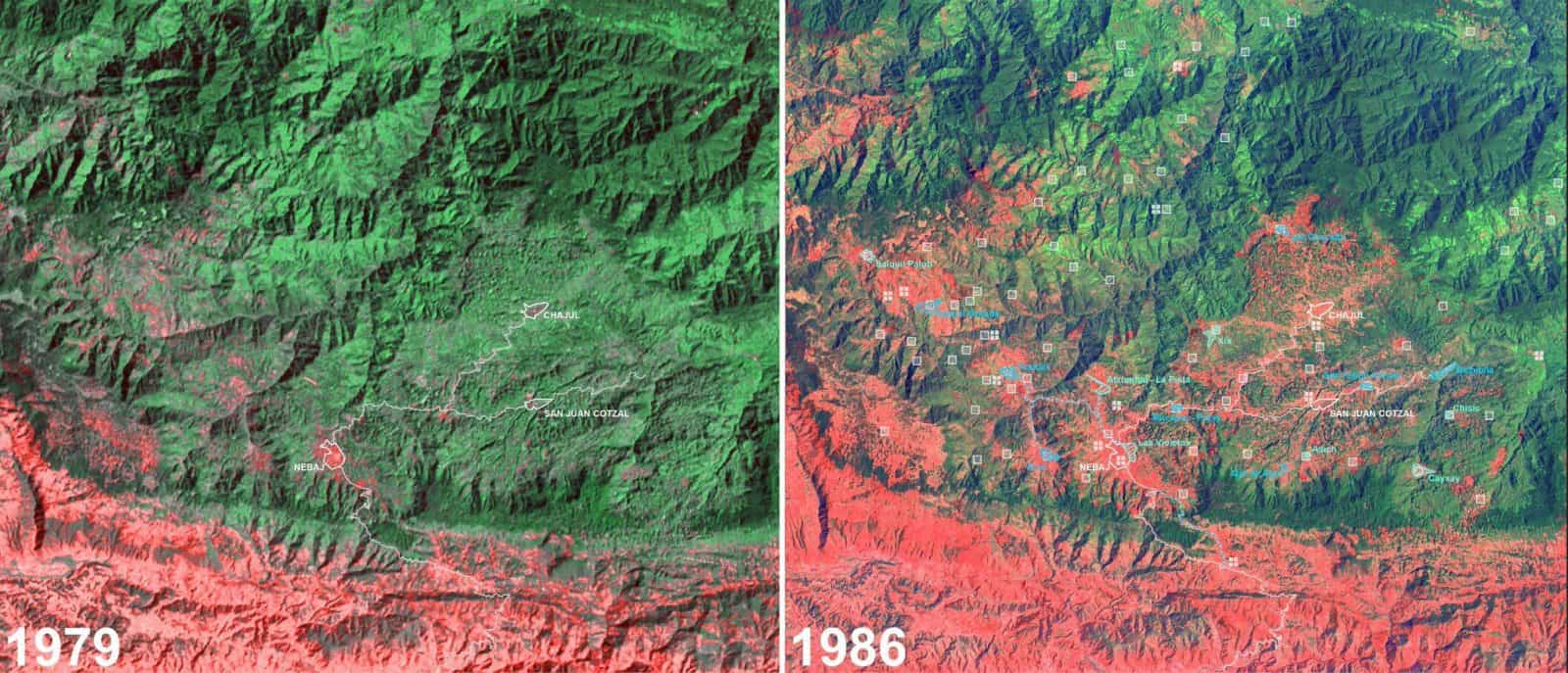

The trial, held at Guatemala’s National Court between 2012 and 2013, examined crimes perpetrated against the Ixil people, a Mayan community indigenous to the highlands of Guatemala, around the cities of Santa Maria Nebaj, San Gaspar Cotzál, and San Juan Chajul, in the region of El Quiché. The area became known as the Ixil Triangle.

By the late 1970s, Ixil villages were seen by the state as the base of an insurgency, and their inhabitants accused of harbouring ‘infiltrating communist cells’. The country’s high mountain areas had given the Ixil a measure of functional autonomy: they were not citizens of the state, and did not participate in the national economy. But this autonomy came to be perceived as a threat to national sovereignty, and the military violence of the late 1970s and 1980s can be understood as less a counterinsurgency campaign, and rather an attempt to ‘domesticate’ the region, and to bring the Ixil into the fold of the state.

Around eighty percent of Ixil villages were razed, and fields and forests were torched. Survivors were forcibly resettled in ‘model villages’, and educated in modern agricultural techniques and monocrop cultivation.

In the case of the violence perpetrated against the Ixil Maya, crimes against humanity and genocide could be understood in relation to transformations of the area’s urban and natural environments. We traced the intersections between military operations, population displacement and relocation, and transformations in the urban, agricultural, and forest areas of the Ixil Triangle during the most violent period of the conflict (1979-1984), with particular attention to the years of the Montt dictatorship (1982-1983). We analysed and subsequently presented that information through a series of time-based cartographies.

Update

10.05.2013

10.05.2013

The trial of Montt and other senior members of his security apparatus concluded at the National Court of Guatemala. Montt was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity.

After Montt’s conviction was overturned in 2013, our research was presented as part of a legal process pursued in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, where the Ixil community had taken its demands for justice.

Update

01.11.2015

01.11.2015

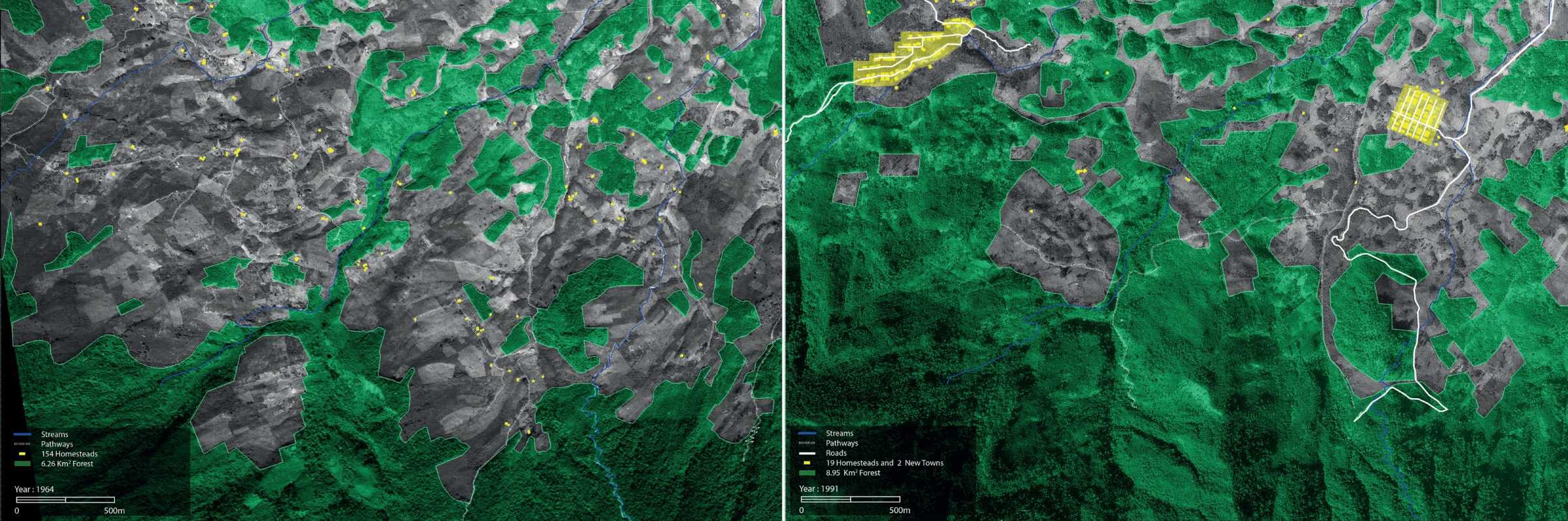

In 2015, ODHAG, a Guatemalan NGO, engaged us to expand our investigation. The CEH had published a detailed report on massacres in three municipalities in the Ixil Triangle: San Juan Cotzal, San Maria Nebaj, and Chajul. ODHAG provided us with the GPS location of the destroyed homesteads in the villages of Xolcuay and Pexla, and using this information, we mapped and presented the layout and structure of these two villages.

We corroborated this information with newly declassified archival aerial images from the US Keyhole-9 satellite, from 1964 and 1991. We mapped the forest areas (represented in green, below) and the location of homesteads and new towns (in yellow). Our analysis showed that many of the homesteads visible in 1964 had been destroyed and removed by 1991, along with with large chunks of forest.

Update

11.06.2024

11.06.2024

In June 2024, Professor Eyal Weizman and Dr Paulo Tavares were called as expert witnesses to present their report The Scorched Earth: Environmental Violence in the Ixil Territory as part of the trial of former general Benedicto Lucas García.

Methodology

Methodology

Our research was based on three periods of fieldwork in Guatemala, undertaken in December 2011, November 2012, and March 2013.

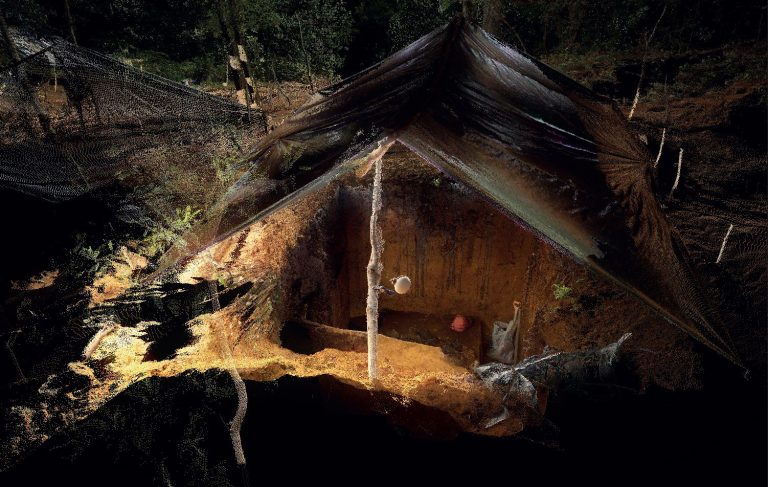

Because the buildings of the Ixil were constructed of wood and adobe, once they were destroyed, their organic remains were quickly consumed by the cloud forest. To identify building remains we learned to follow the plants: fruit trees such as avocado, papaya, or peach signalled the possible former presence of house and village sites. Building foundations had been made of stone, but more than thirty years of overgrowth made it necessary to first probe the ground with sticks to find their harder surfaces, then clear the shrubs with a machete to measure the extent of the ruin.

We examined aerial images from 1964, 1978 and 1991, collected from Guatemala’s Instituto Geografico Nacional, and from declassified material from the US Keyhole-9 satellite. We used various methodologies to interpret those and other images, particularly the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a technique that assesses photosynthetic activity in plants to identify changes in land cover over time.

We showed that the transformation of environmental and territorial organisation in the Ixil Triangle was an important medium of military violence.

Through massacres, forest and crop destruction, population displacement and transfer, closure of common lands, and psychological warfare, state security forces not only tightened their control over the rural population, but disrupted on the political-natural connections between those communities and their land, in such a manner as to undercut the basis of the existence of the Ixil Maya as a distinctive culture.