This investigation marks the launch of the Febrayer Network / Forensic Architecture (FFA) Investigative Lab, collaboratively established to employ Forensic Architecture’s methodologies and techniques for monitoring and documenting human rights violations in pursuit of accountability in the Arab world.

This investigation is also part of a broader project examining the 4 August 2020 explosion in the port of Beirut, its causes and aftermath. See also:

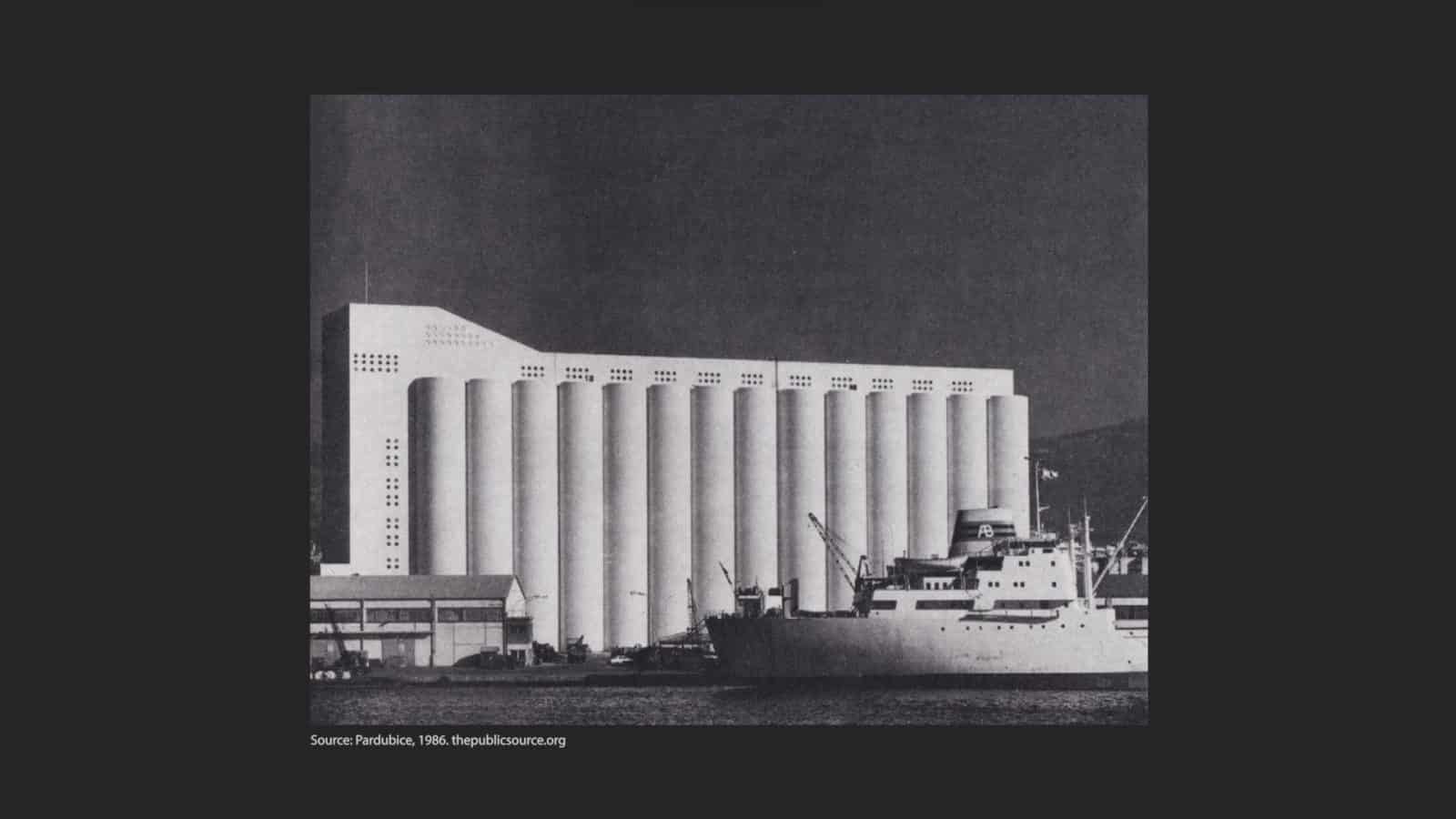

Since the 1970s, the Beirut grain silos have marked the seam between the city and the sea. Ships from the Soviet Union and later Russia and Ukraine loaded with barley, corn, and wheat docked regularly in the port to unload these vital food staples. Forty-two concrete cylinders with a capacity to store up to 120,000 tons of grain, enough to make bread for up to 1.7 million people, guaranteed Lebanon’s food security.

The Beirut port explosion on 4 August 2020 ripped through the city, destroying 70,000 homes and much of the port area and leaving over 300,000 people homeless. Caused by the detonation of vast quantities of ammonium nitrate improperly stored in a warehouse by the port, the blast sent powerful shockwaves through the city. The silos, located just 75 metres from the epicentre of the explosion, became a site of ruin.

Since the explosion, these ruins have loomed large in the city’s skyline as a constant reminder of the devastation that followed the blast. For some, the ruins of the silos also evoke the persistent lack of accountability for the tragedy, and are a potential source of valuable evidence.

‘The material function of what remains of the concrete building has become a sharp symbol in the conscience and memory of the families of the victims, and the Lebanese population at large. It is a witness to a crime whose perpetrators have not yet been revealed.’

—Statement by the Solidarity Campaign to Protect the Silent Witness, Legal Agenda, 5 August 2022

On 7 July 2022, almost two years after the blast, a fire broke out at the base of the silos. After six days, the Lebanese Armed Forces extinguished the fire, setting off a rapid cooling of the structure. This pattern of intermittent heating and cooling would continue over the next month, until what had remained of the north part of the silos collapsed.

In late July, a first section of the northernmost block of silos collapsed. A few days later, on the two-year anniversary of the explosion, an additional section of the block followed suit.

To understand how the gradual destruction of a ruin – the destruction of destruction – happened behind state cordons in the nearly two-year period since the explosion, Febrayer and Forensic Architecture have threaded together previously unseen drone footage from two days after the explosion, open source videos, images, and published research to reconstruct the site of the silos and present a unified account of the state’s mismanagement of this important site of material evidence and memory.

We have made the model available as an open source asset here.

Methodology

Methodology

Photogrammetry

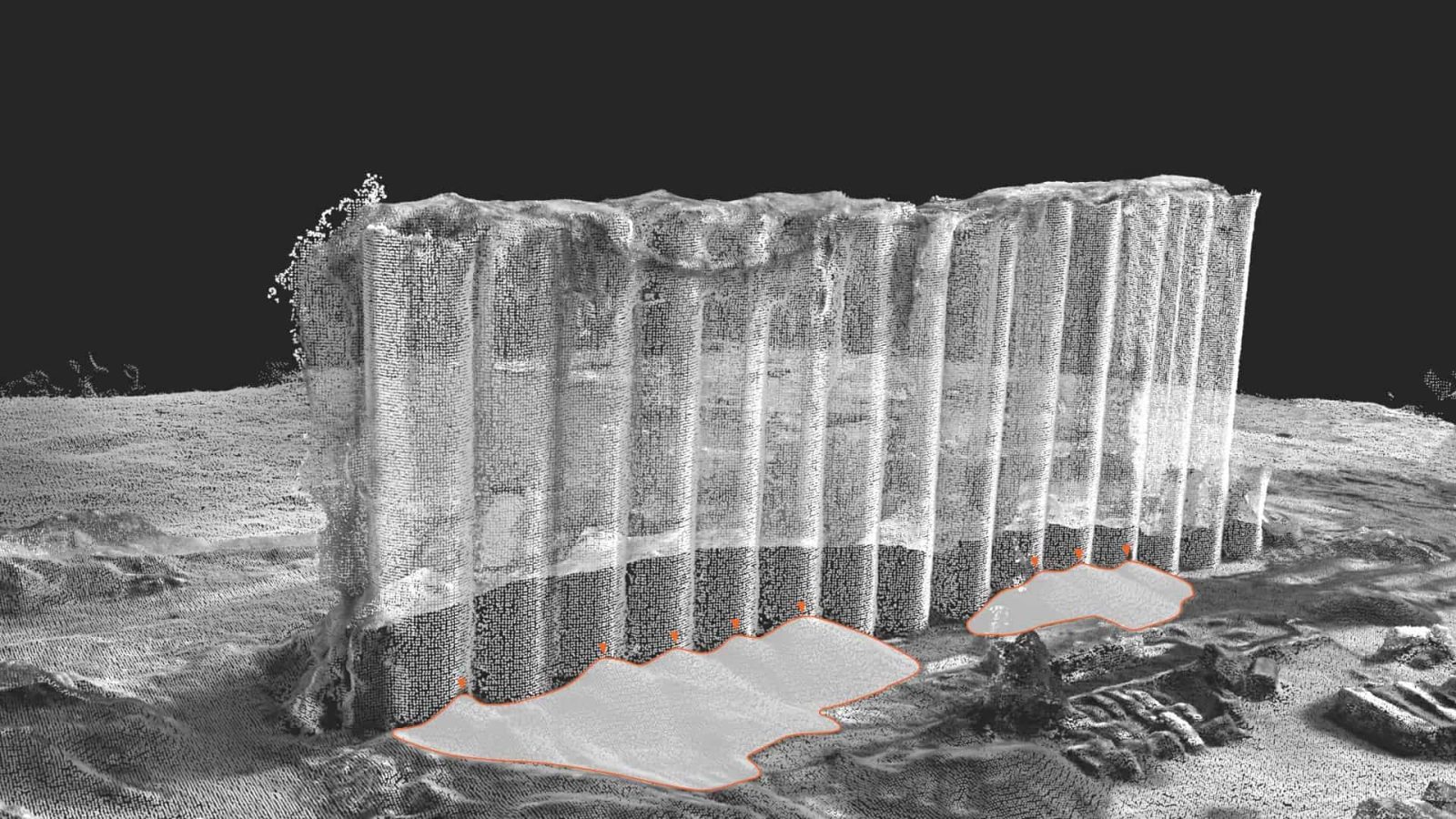

We reconstructed an accurately measurable model of the aftermath of the 4 August explosion, using drone footage taken on 6 August 2020, two days after the explosion, and photogrammetry of the Beirut port silos and their surroundings, within which a range of open source videos, images and scientific studies could be located.

3D modelling and image analysis

We collected and examined images and videos taken and posted online by witnesses to the protracted fire. An image from 13 July 2022 allowed us to determine the growth of the fire, fuelled by fermented grains at the base of the silos, to reach approximately 250 square metres.

Shortly after the fire was detected by the residents of Beirut, the state responded with an attempt to extinguish the blaze and cool down the structure on 16 July 2022, six days after the fire started. Building on these open source images and videos, we tracked the state’s response. The fire ignited again on 21 July , and was again cooled down through the intervention of the Lebanese Armed Forces. Fire engineers at Kindling Safety, a non-profit dedicated to fire safety, explained that this process of heating and rapid cooling could have also contributed to the collapse of the structure on 31 July.

The collapse of the northern part of the silos unfolded in three stages, over 31 July, 4 August, and 23 August 2022. To understand why the state failed to prevent the fire from the very outset, we examined the interventions at and around the site over the course of the two years prior.

Satellite imagery clearly shows that the site had been consistently worked upon behind the cordons put in place by state authorities.

A comparison between our models of the silos on 5 August 2020 and 3 February 2021 reveals that, while the authorities removed a significant quantity of the spilled grain located at the base of the silos, they failed to remove all of it.

These topographic maps, generated from the models, consist of contour lines corresponding to 1 metre each. We used them as an analytical tool to estimate the volume of the remaining grain, arriving at a total of approximately 10,000 tonnes of grain.

In an interview, the engineer monitoring the structure reveals that these fires started igniting as early as December 2020, only a few months after the explosion. Our model from 3 January 2021 shows piles of grains amassed at the base of the silos.

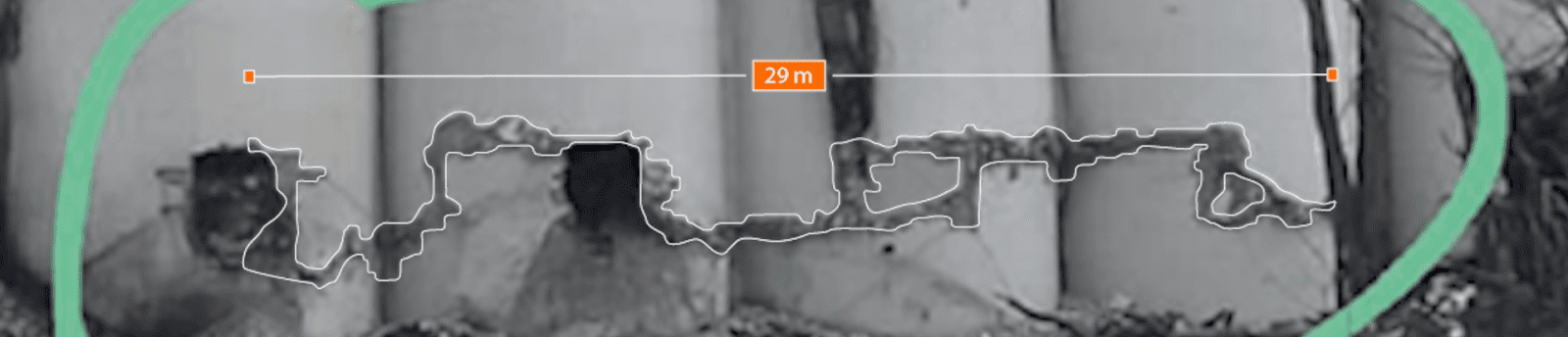

To empty the grains, a series of holes were drilled into the base of the silos. We mapped the shape of the holes, using existing photographic documentation. Our analysis showed that the holes drilled did not adhere to expert specifications that recommended significantly smaller circular holes. We can also see cracks spreading from the irregular openings’ sharp corners, gradually moving along the concrete structure’s lines of least resistance. After the second collapse on 4 August 2020, the cracks appear to expand around the openings, spreading to adjacent columns where holes were not even drilled.

We studied the changes in the structure of the silos over two years. Our analysis reveals that in April 2021, the tilt of the south silos stabilised, while the tilt of the north silos increased rapidly in the direction of the crater. This severe tilt was recorded shortly after the drilling of the holes at the base of the silos, calling into question the degree of damage caused by the large holes on the structure. By March 2022, a year later, the speed at which the tilt was worsening decreased. But it is the rapid changes in temperatures from the July 2022 fire that ultimately brought about the collapse.