Date of Incident

Publication Date

Commissioned By

- Michael Sfard Law Office

- B’Tselem

Additional Funding

Collaborators

- SITU Research

- Michael Sfard Law Office

- B’Tselem

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

On 17 April 2009, near the village of Bil’in, Bassem Abu Rahma was shot and killed by a tear-gas canister fired across the fence of the barrier wall that surrounds the West Bank. Abu Rahma was attending a protest, and was unarmed.

The protest occurred at a location that had been declared a ‘closed military zone’ by Israeli authorities four years earlier. Since then, non-violent activists were routinely arrested and imprisoned in the area.

In the context of such encounters, official instructions allow soldiers to use only ‘non-lethal means’, such as tear gas and rubber-coated bullets, unless their lives are in danger. But while tear gas is considered a ‘non-lethal’ munition, when the aluminum gas canister hits a human body directly, the impact can be fatal. Soldiers are only supposed to shoot these munitions upward, at a trajectory of 60 degrees, above a crowd.

Following Abu Rahma’s death, the military denied responsibility, claiming that soldiers did not fire the canister directly at the victim. Authorities suggested he might have been struck as a result of an unfortunate deflection, and closed the investigation.

However, the killing was recorded by three cameras, from different angles. Forensic Architecture (FA) was commissioned to reconstruct the event by the Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem, and human rights lawyer Michael Sfard, acting for Abu Rahma’s parents.

One of the three people filming that day was David Reeb, an Israeli artist and activist who was standing next to Abu Rahma when he was shot. Reeb’s footage showed a group of Israeli soldiers on the opposite side of the separation barrier. A few seconds later in his footage, a single still frame captured a faint and blurry streak: the projectile moving horizontally in mid-flight. Three frames later, the canister strikes Abu Rahma, who is heard calling out in pain.

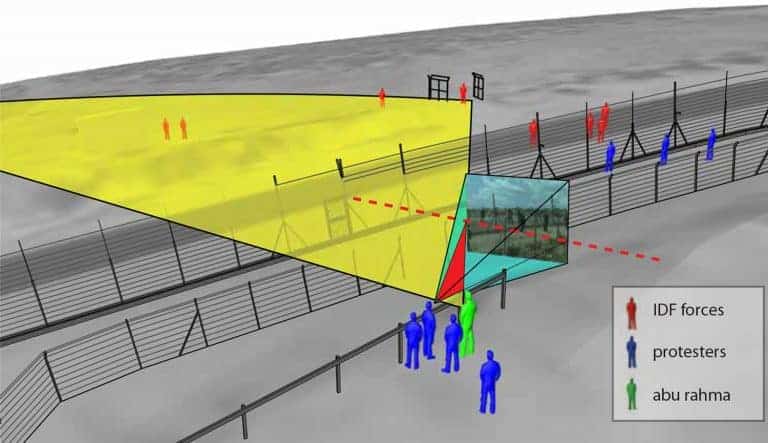

We located the videos and the participants in a 3D model and demonstrated that the lethal strike was fired with the intention to kill or maim.

Update

03.04.2014

03.04.2014

A ‘counter-expert report’ was produced by the Israeli Defence Forces, signed by a ‘Lieutenant Colonel Naftali XXXXX’—his surname was crossed out.

The anonymous Lieutenant Colonel was presented as the ‘Senior Deciphering Officer of the IDF Intelligence Corps’. His report claimed that the streak we identified in the video ‘has not directly hit Abu Rahma’, and provided drawings that attempted to explain his determination.

Update

25.07.2014

25.07.2014

We submitted our formal response to the IDF report. We argued that it was impossible to analyze the movement of a projectile in space based on 2D images only. Photographs and video stills need to be located within 3D models to determine relations between elements which are otherwise flattened on the 2D surface of the image.

We provided a set of models that reconstructed the scene in 3D, and located the projectile in space. Our models showed that the projectile had to have passed only a few centimetres from the lens of the camera to be captured as a streak.

Lieutenant Colonel ‘XXXXX’ was forced to agree that the canister was fired directly, but subsequently claimed that the military police do not know who the soldiers seen in our video analysis are, and that they have not as a result been able to interview them.

Update

16.09.2018

16.09.2018

The Israeli High Court ruled that while the Military Police and Judge Advocate General (an internal military investigator) did act negligently, including in losing their case file of the investigation. The implication is that no individuals should face charges, or be considered responsible for the death of Abu Rahma.

Methodology

Methodology

Understanding that it was impossible to analyse the movement of a projectile in space based on 2D images alone, we located photographs and video stills within 3D models. This allowed us to determine relations between characters, objects, points of origin, and trajectories that would otherwise have been flattened on the 2D surface of the image.

For the first time in Forensic Architecture’s history, we produced a set of models that constructed the scene in three dimensions and located the fatal projectile in space. One such model demonstrated that the projectile had to have passed only a few centimetres from the lens of the camera to be captured as a ‘streak’ across a single frame.

A panoramic collage of still frames from another camera helped to further reconstruct the sequence of events.