Commissioned By

Additional Funding

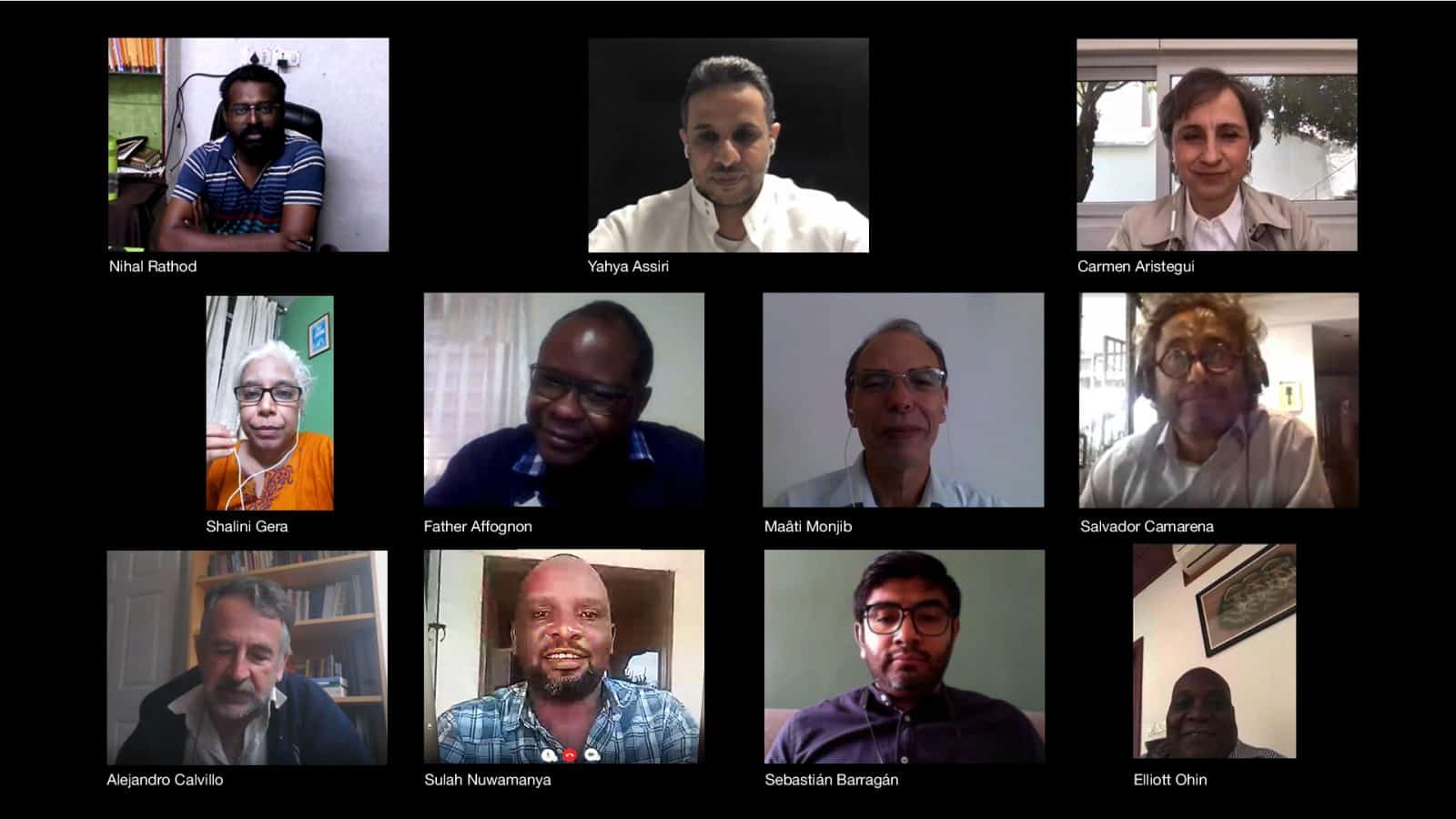

Collaborators

In March 2020, with the rise of COVID-19, Israeli cyber-weapons manufacturer NSO Group launched a contact-tracing technology named ‘Fleming’. Two months later, a database belonging to NSO’s Fleming program was found unprotected online. It contained more than five hundred thousand datapoints for more than thirty thousand distinct mobile phones. NSO Group denied there was a security breach. Forensic Architecture received and analysed a sample of the exposed database, which suggested that the data was based on ‘real’ personal data belonging to unsuspecting civilians, putting their private information in risk.

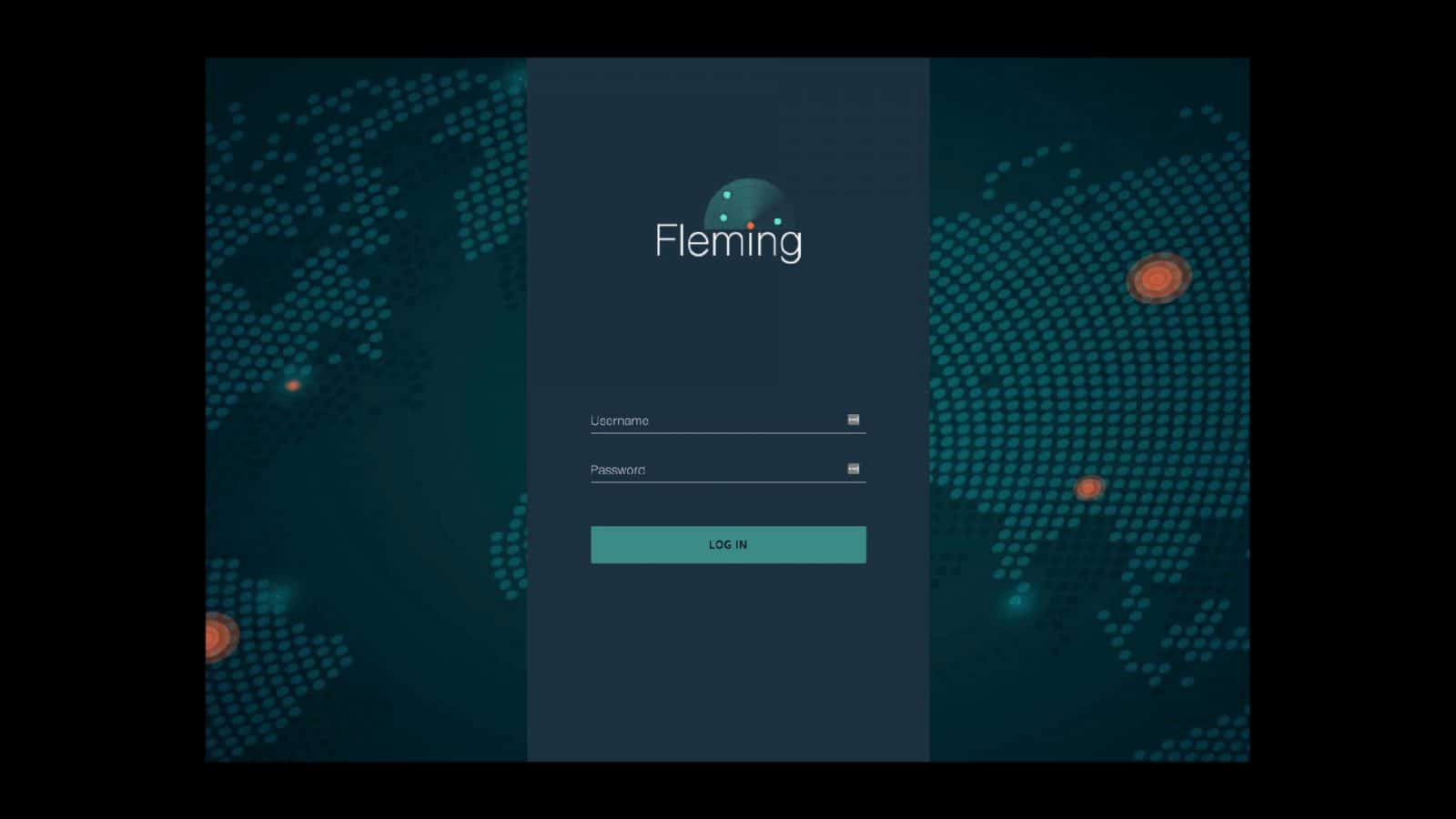

‘Fleming’: COVID-19 Tracing Software

On 17 March 2020, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Israeli cyberweapons manufacturer NSO Group launched a contact-tracing software named Fleming. NSO claims that Fleming is designed to track the location and movement of mobile phones without collecting personal data.

Promoted by former Defense Minister Naftali Bennett, NSO has since demonstrated Fleming to a dozen health ministries—including the U.S. health authorities—as part of a marketing push aimed at western governments.

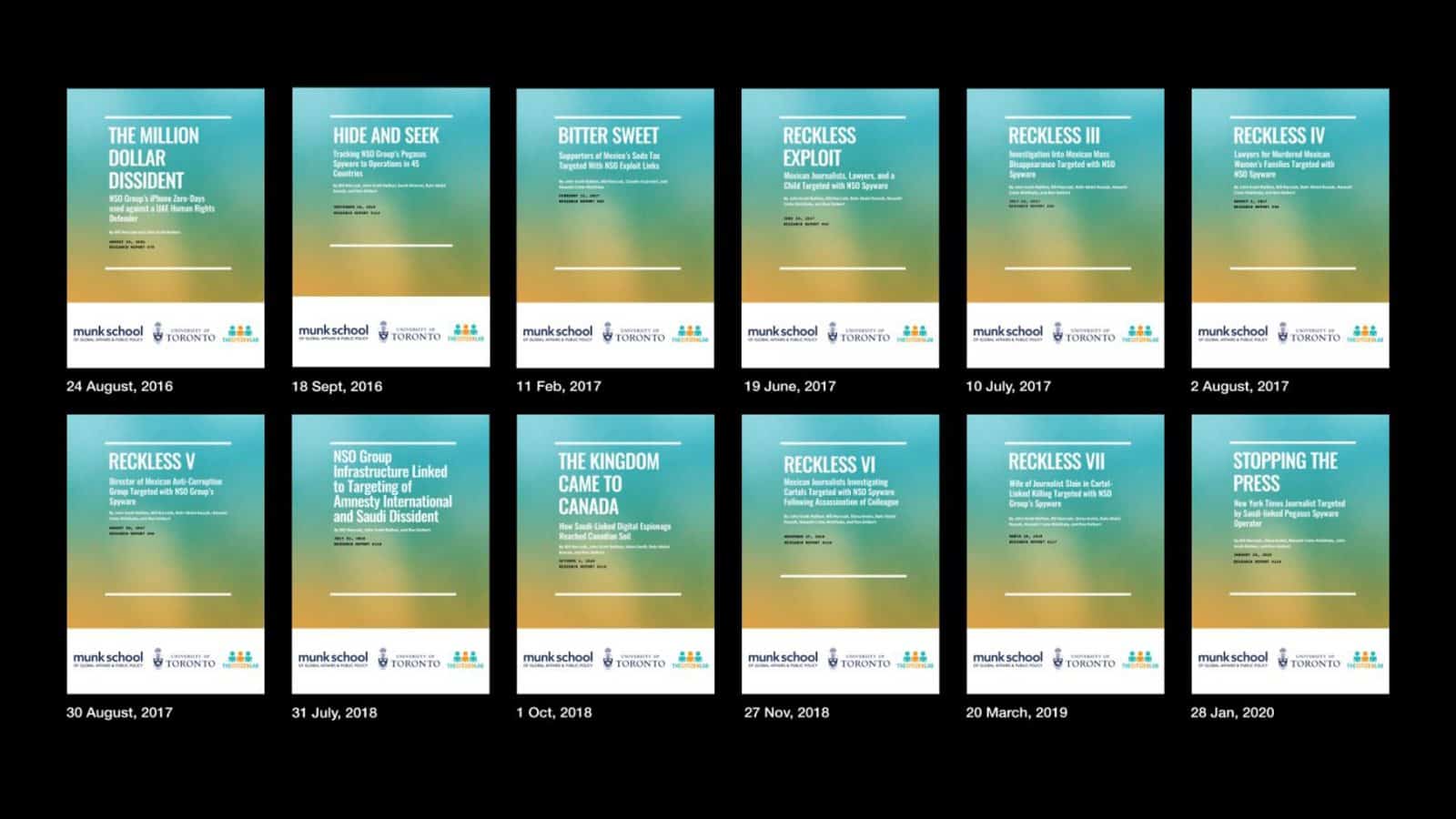

NSO is better known for ‘Pegasus’—a malware sold to governments to enable the remote infection and surveillance of private smartphones. In order to sell and operate Pegasus, NSO needs Israel’s Ministry of Defense to provide a security export license.

First discovered in 2016, Pegasus has reportedly been used to surveil and intimidate prominent human rights defenders, opposition figures, religious leaders, dissidents, and journalists—several of whom are our close collaborators—in at least 45 countries across the globe.

Reports:

- The Great iPwn: Journalists Hacked with Suspected NSO Group iMessage ‘Zero-Click’ Exploit

- Nothing Sacred: Religious and Secular Voices for Reform in Togo Targeted with NSO Spyware.

- The Kingdom Came to Canada: How Saudi-Linked Digital Espionage Reached Canadian Soil

- NSO Group Infrastructure Linked to Targeting of Amnesty International and Saudi Dissident

- Reckless Exploit: Mexican Journalists, Lawyers, and a Child Targeted with NSO Spyware.

As a company whose software is designed to violate a person’s privacy, NSO’s involvement in COVID-19 tracing with health ministries, and the possibility that it may have access to our private health data raised serious ethical, political, and data-security concerns.

Unprotected Database

On 7 May, 2020, a private cybersecurity researcher, Bob Diachenko, discovered an unprotected database belonging to NSO.

Forensic Architecture received a sample of the exposed database.

The data we received contained more than five hundred thousand datapoints for more than thirty thousand distinct mobile phones during a period of six weeks, from 10 March to 13 April 2020.

A ‘datapoint’ provides information about the different time intervals at which an individual target was spotted at a certain location. Some of these datapoints are marked with start and end times, or a ‘last seen’ stamp.

Leaving a database with genuine location data unprotected is a serious violation of the applicable data protection laws. That a surveillance company with access to personal data could have overseen this breach is all the more concerning.

Denying that this was a security oversight, Oren Ganz, a director at NSO, stated:

‘The Fleming demo is not based on real and genuine data. [….] The demo is rather an illustration of public obfuscated data. It does not contain any personal identifying information of any sort.’

NSO also denied acquiring the location data from a data broker.

The statements made by NSO are unclear and appear to be contradictory. ‘Real data’ is data derived from the actual location and movement of real people and underlying users. ‘Obfuscated data’ is ‘real data’ that has gone through a process where spatial and temporal locations are changed to impede the re-identification of individuals, or to reconstruct personally identifying information.

After informing NSO of the unprotected database, Diachenko later claimed that it contained ’dummy data’—a term which refers to simulated, computer-generated data used for testing or demonstration.

Breach of Privacy?

The sample of the exposed database we received has over 149,000 data points. Given the high stakes related to the possible violation of personal information attached to the type of data left open, we sought to establish whether NSO’s statements are truthful. We investigated the nature of the data: whether it was based on ‘real’ personal data belonging to many unsuspecting civilians and, if so, whether it was properly obfuscated in a way protecting private identities, or if it was ‘dummy’ data.

When presenting our analysis below, we went to great lengths to anonymize the data using pixelation, removing background maps to signal locations, and limiting the presentation of datapoints per individual in the dataset to prevent their possible re-identification—a standard of protection that NSO failed to meet by leaving this database exposed.

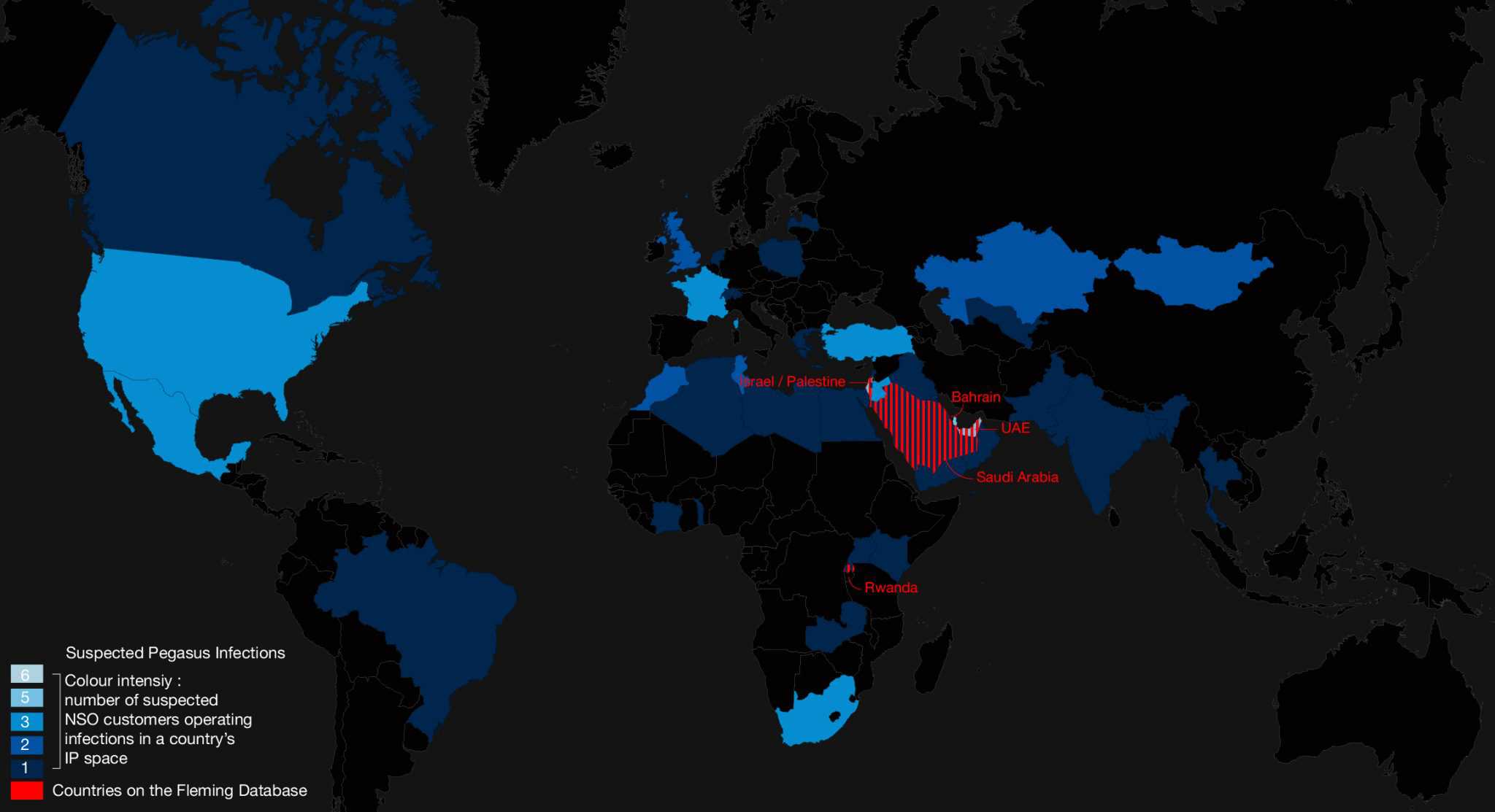

We first looked at the general geographic distribution of the datapoints. Importantly, the exposed data included location information from Rwanda, Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain—all countries in which NSO’s Pegasus spyware was reportedly used.

The dataset we analysed contains space and time coordinates of the electronic devices of almost 32,000 supposed ‘targets’—the term used by NSO to refer to people whose movements were tracked.

Plotting the Data in Time and Space

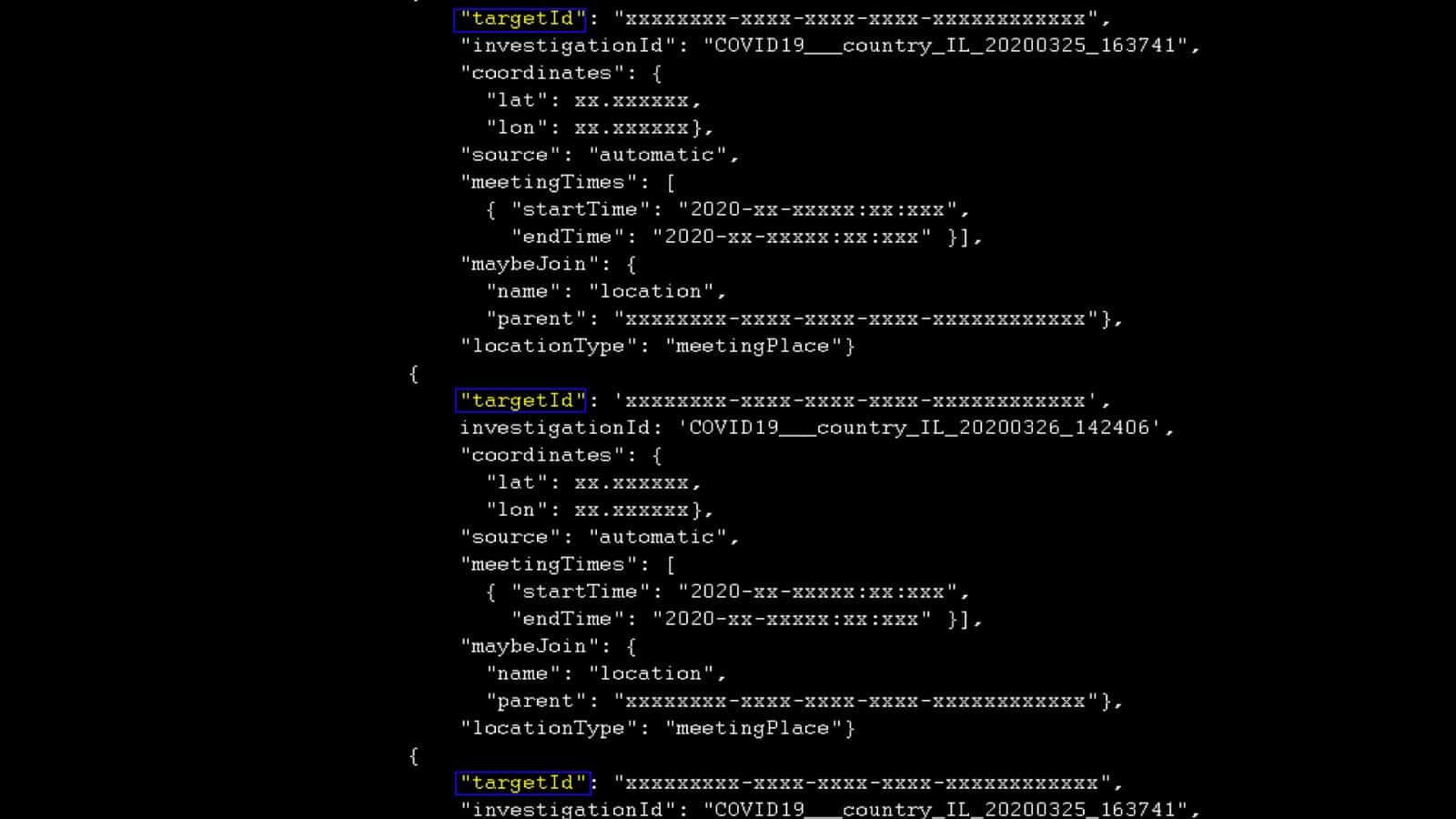

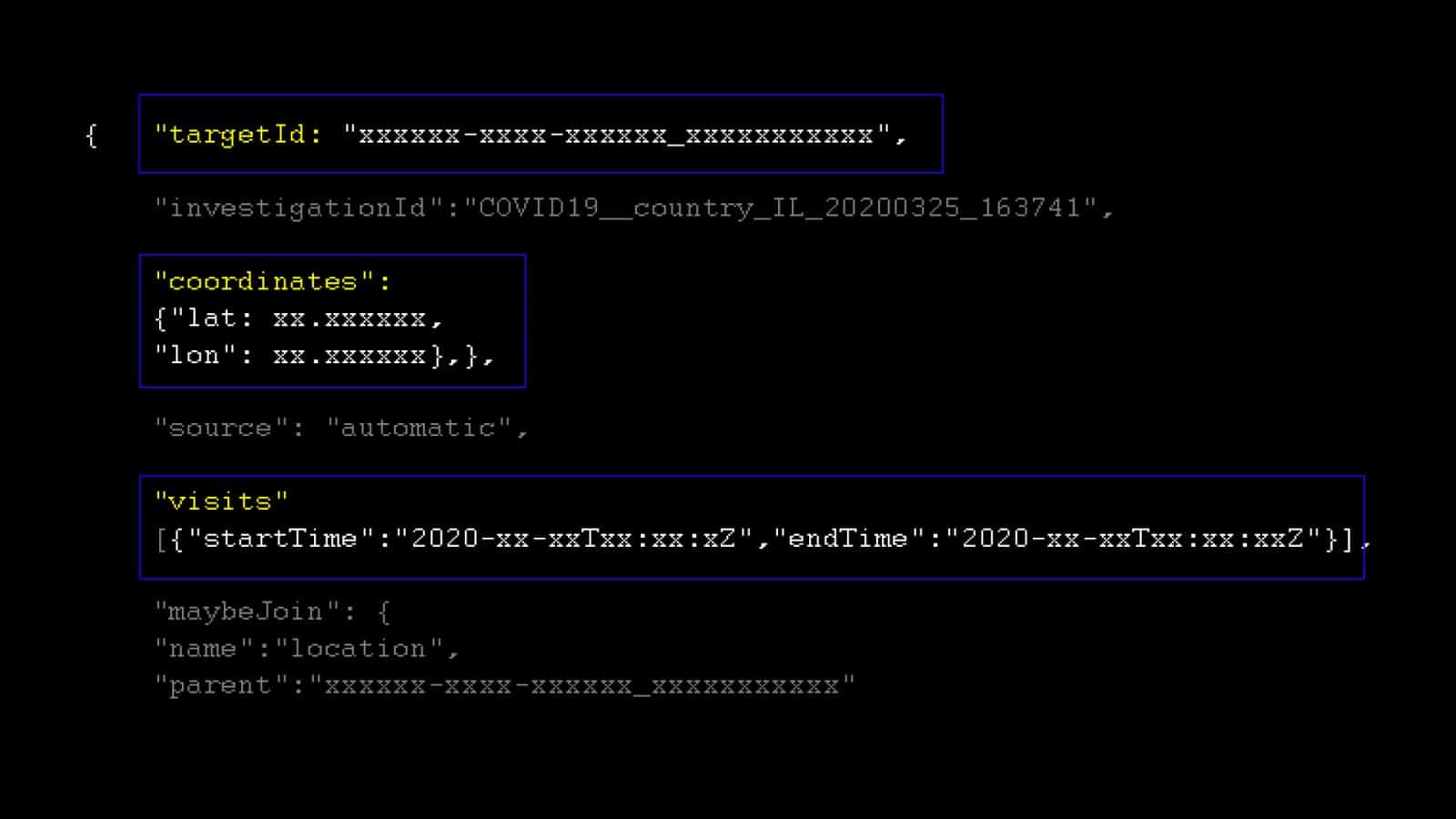

Each line of data or ‘target ID’ included geographical coordinates and time attributes.

We plotted the data in our open-source software TimeMap, which can make visible patterns and rhythms in space and time. We examined these patterns to assess whether they were synthetically generated, or whether they could represent data belonging to ‘real’ users.

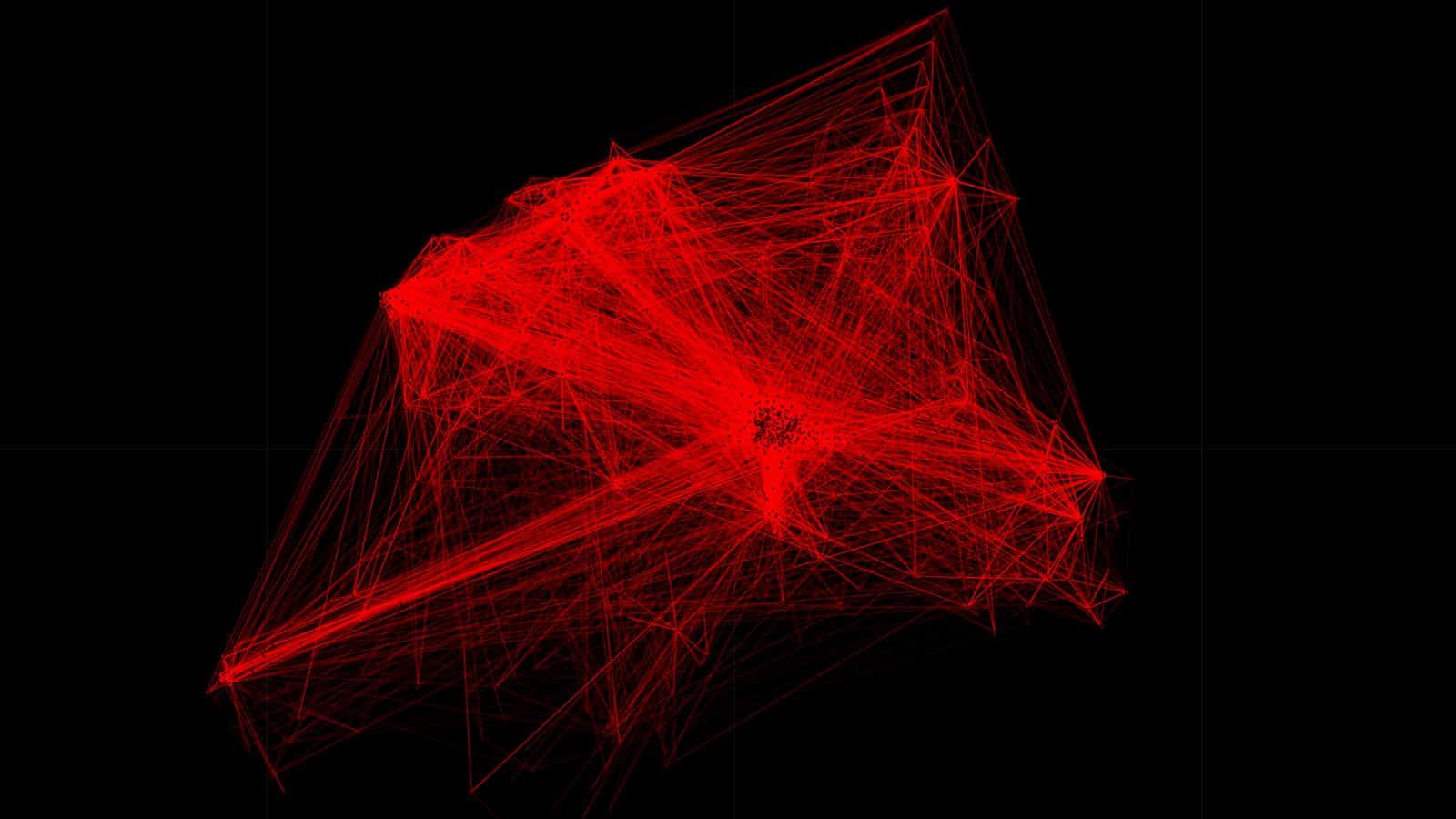

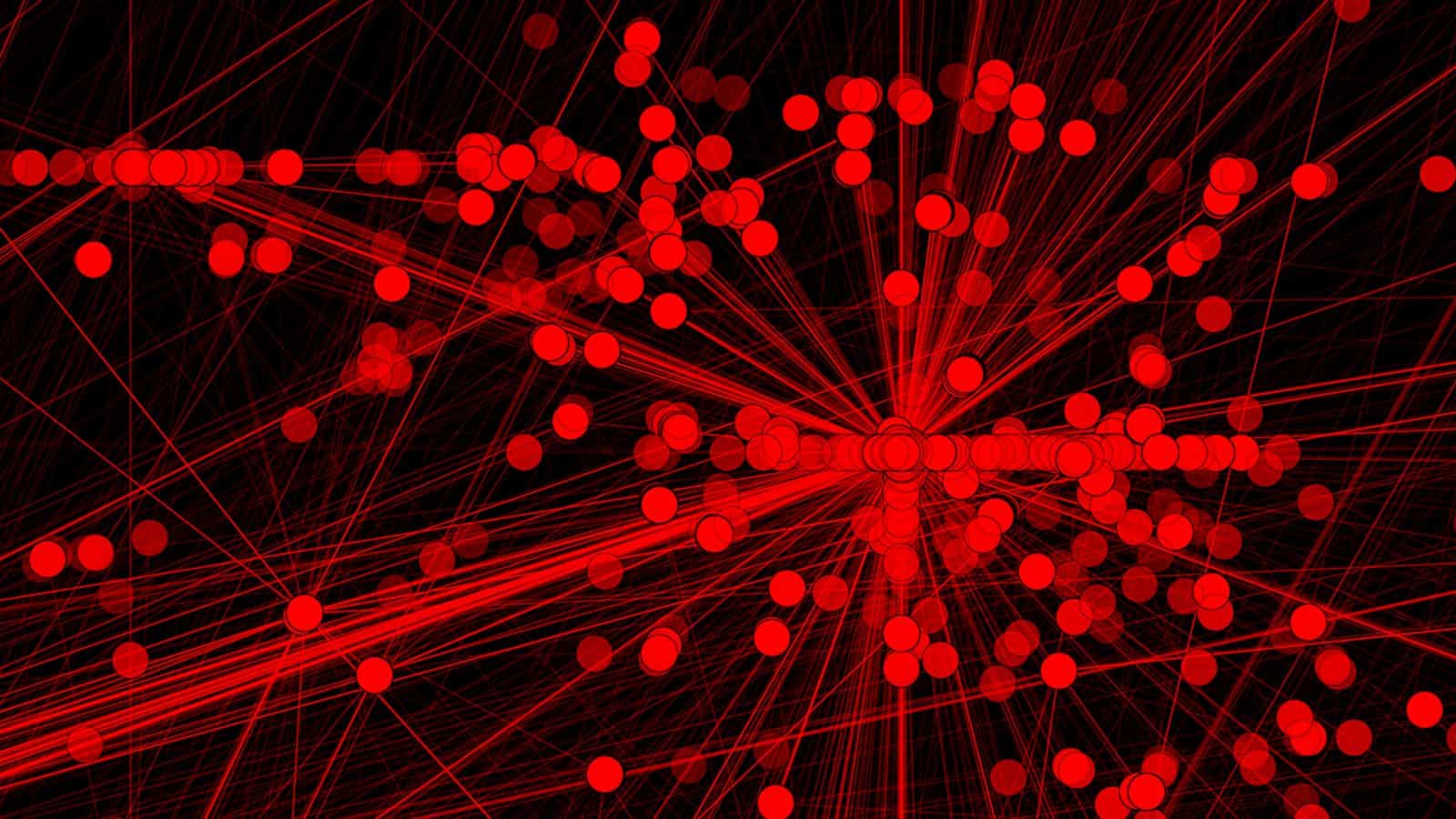

This is the entire dataset we received, with the map removed to preserve the anonymity of these individuals. The diagrams below show the amount and density of location points and movement trajectories.

As seen in the visualization below, within their individual countries, the sample of locations we received were largely concentrated in major cities and urban areas. The data here is pixelated to preserve anonymity, with the brighter spots indicating a greater concentration of points.

We measured the distance between points in time and space for individual ‘targets’, to examine the timeline of their movements.

In this graph, circles represent distinct locations. Red lines represent the reasonable movement through space and time of individual ‘targets’ where the distance traveled is plausible within the indicated time—while white lines represent less plausible movements, as compared to more common urban patterns.

The ‘target’ timelines and the movements reflected in the visualisation followed the urban patterns of movement that one would expect to see in real data, given common urban patterns of circulation and use, while the less common patterns are limited.

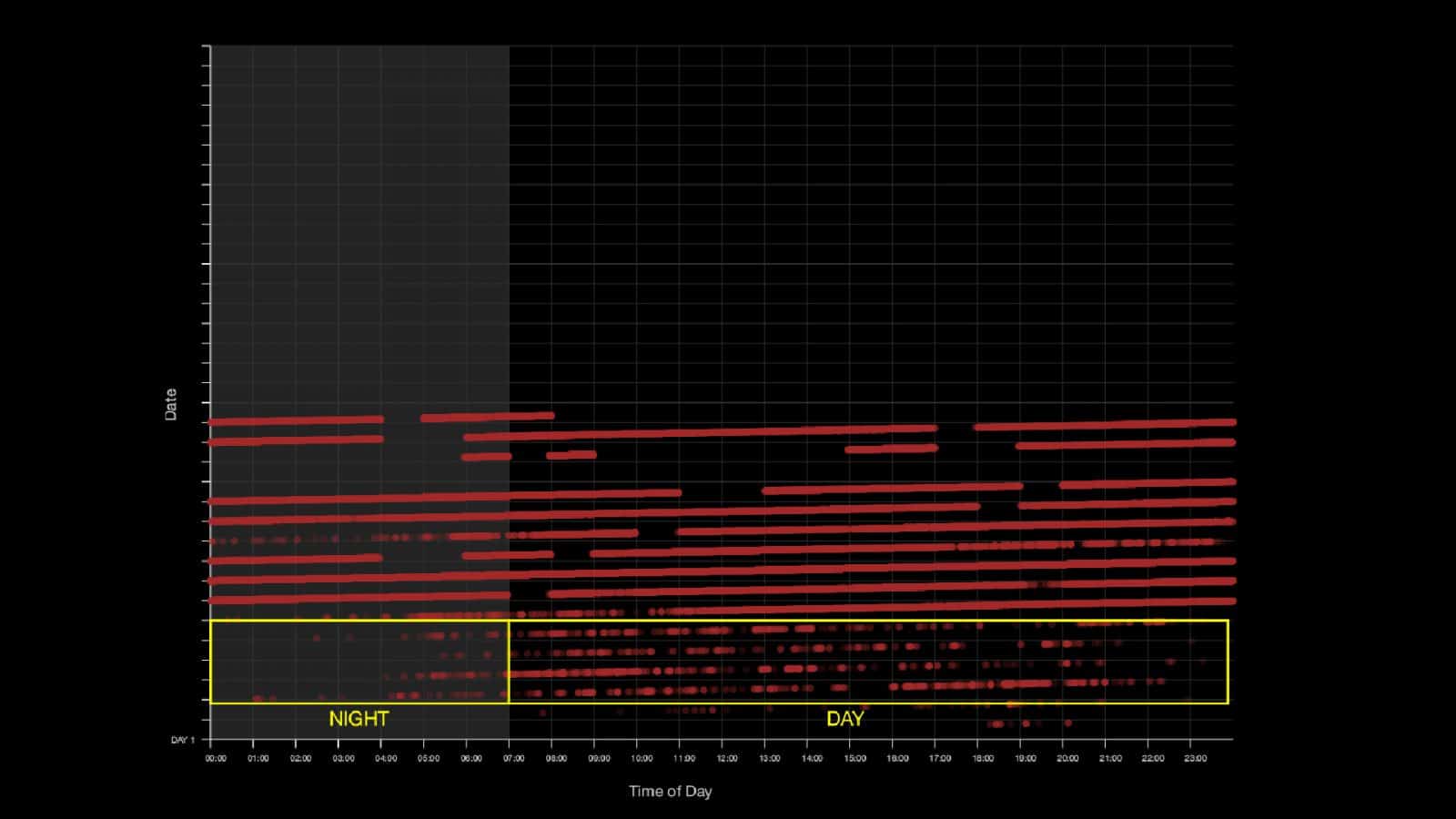

We further plotted the points according to time-of-day, using the timestamp in every datapoint to determine whether the patterns seen could be consistent with real mobile phone data.

In some cases, we see that the points follow day/night patterns, wherein the datapoints are more common during the day, reflecting common commute patterns of individual devices.

We also identified apparent spatial irregularities within the mapping of the data. The patterns and other phenomena we detected in the plotted data are common examples of ‘errors’ in spatial data that are typically indicative of real location data in an urban environment.

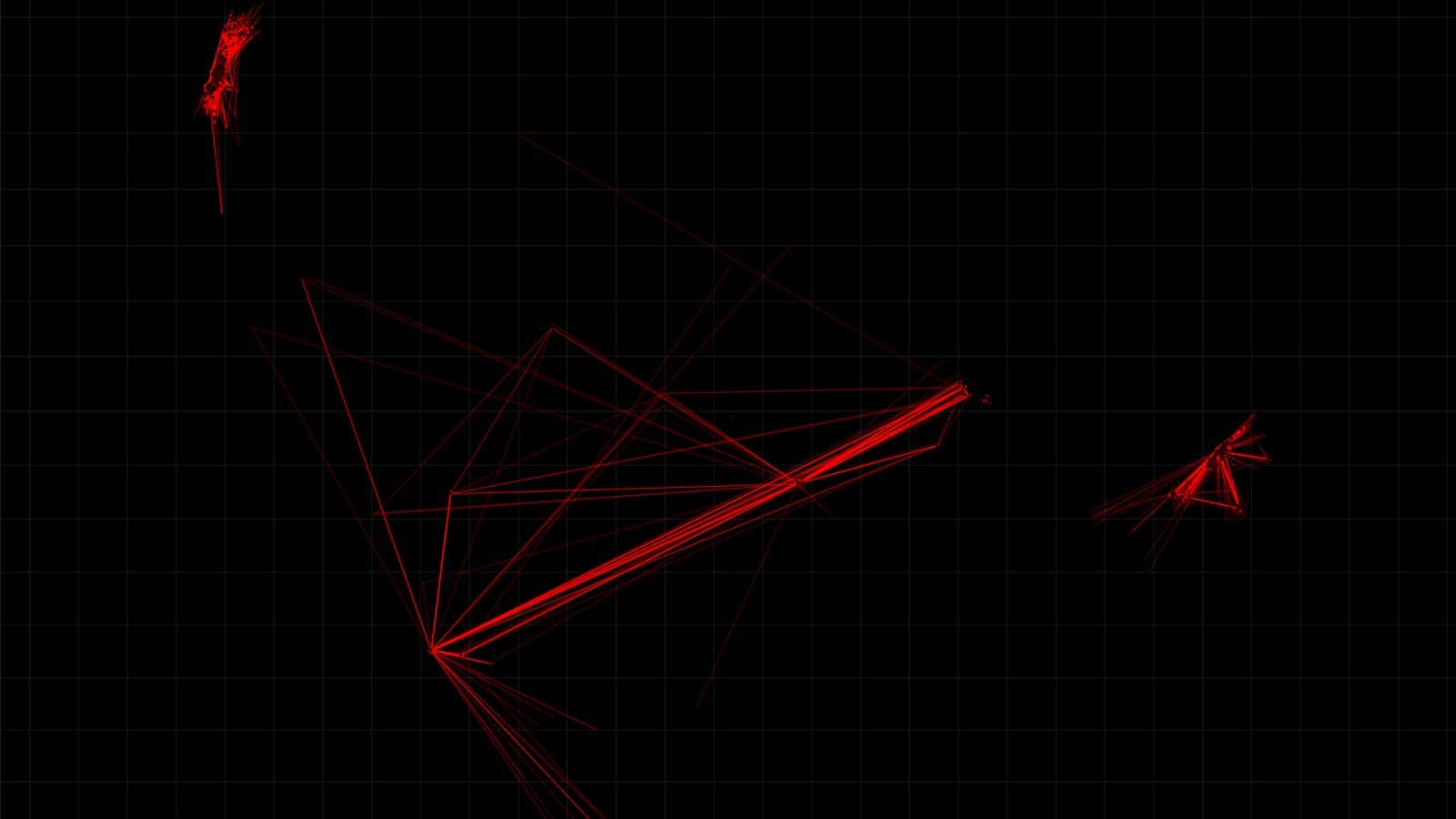

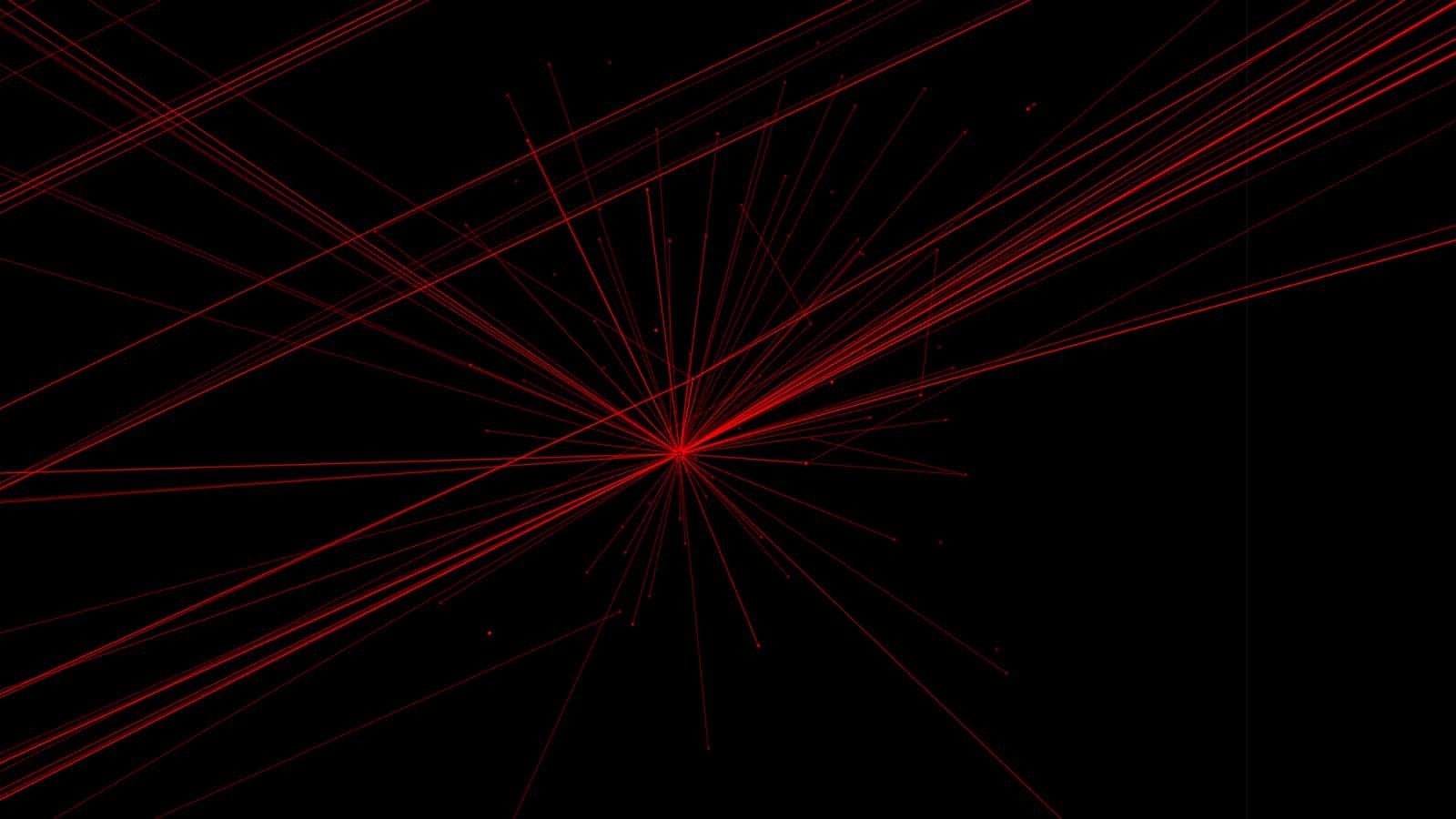

Once plotted, multiple ‘target’ movements revealed such patterns, including these ‘star-like’ patterns in Saudi Arabia and Rwanda as seen in the diagram below. Star-like patterns and lines can be indicative of errors such as spatial ‘drift’ caused by the GPS trying to obtain an accurate fix on a position, or by other forms of cell tower-based triangulation, resulting in inaccurate location points.

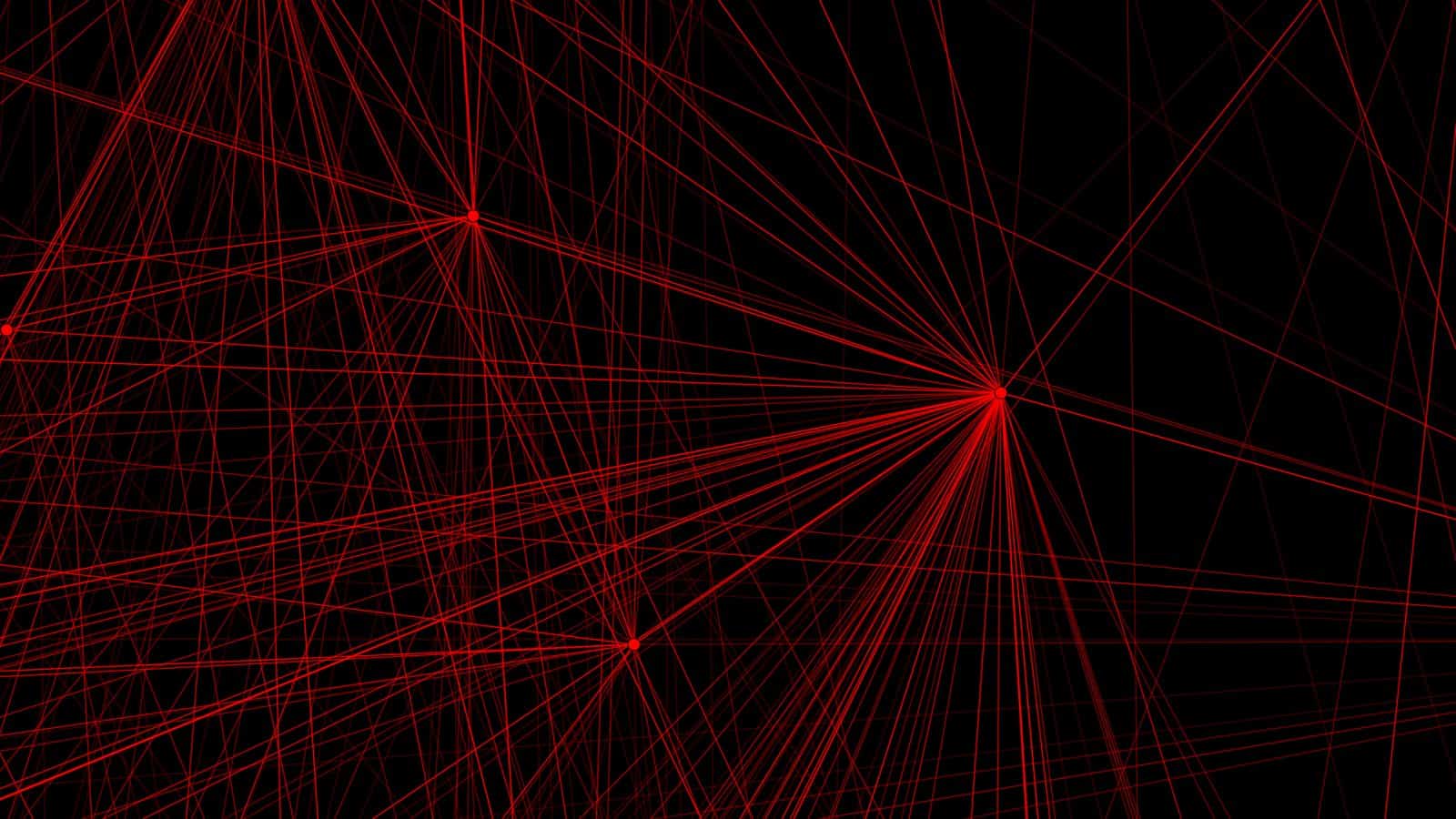

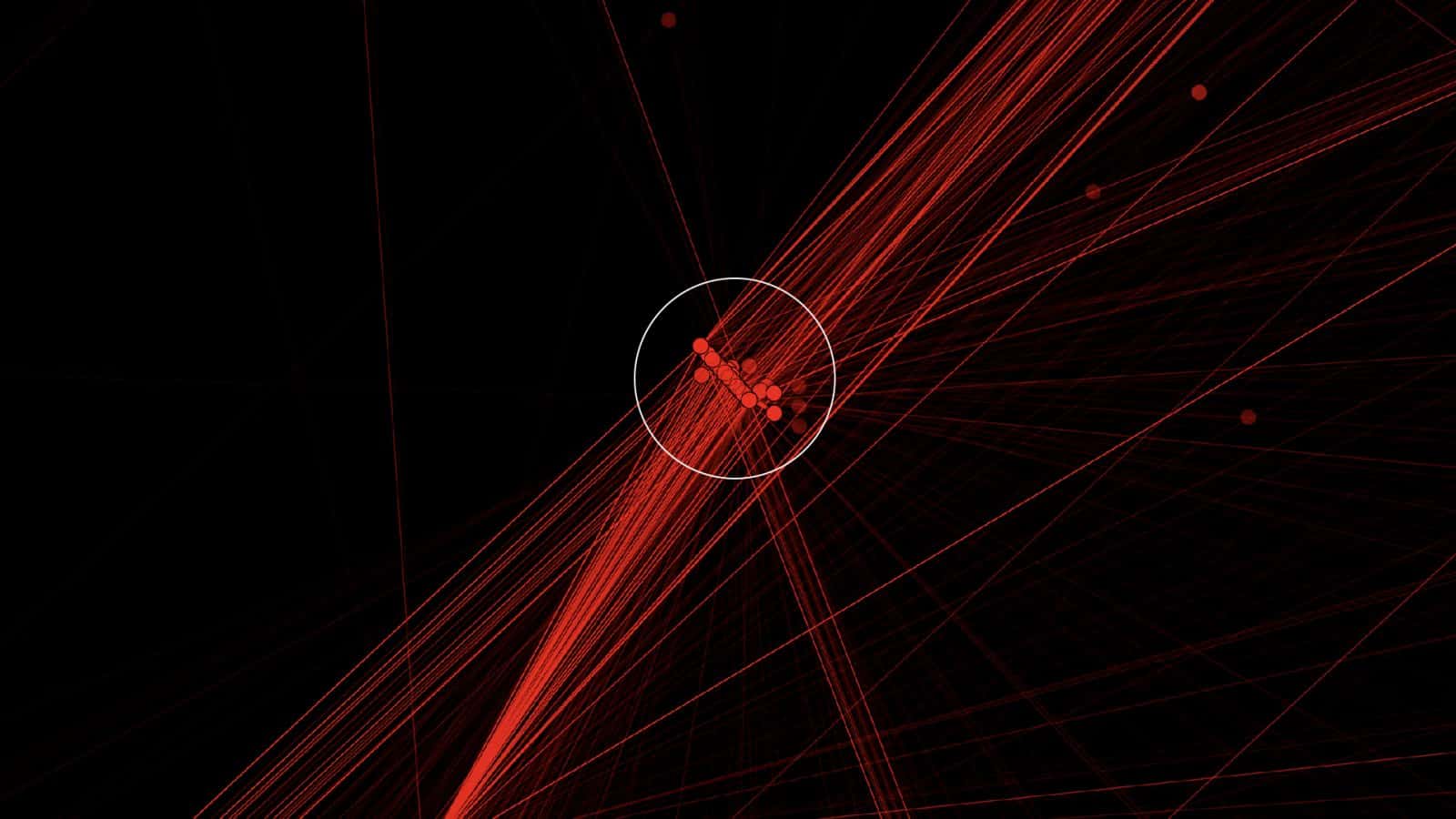

We also detected these straight lines in Israel/Palestine:

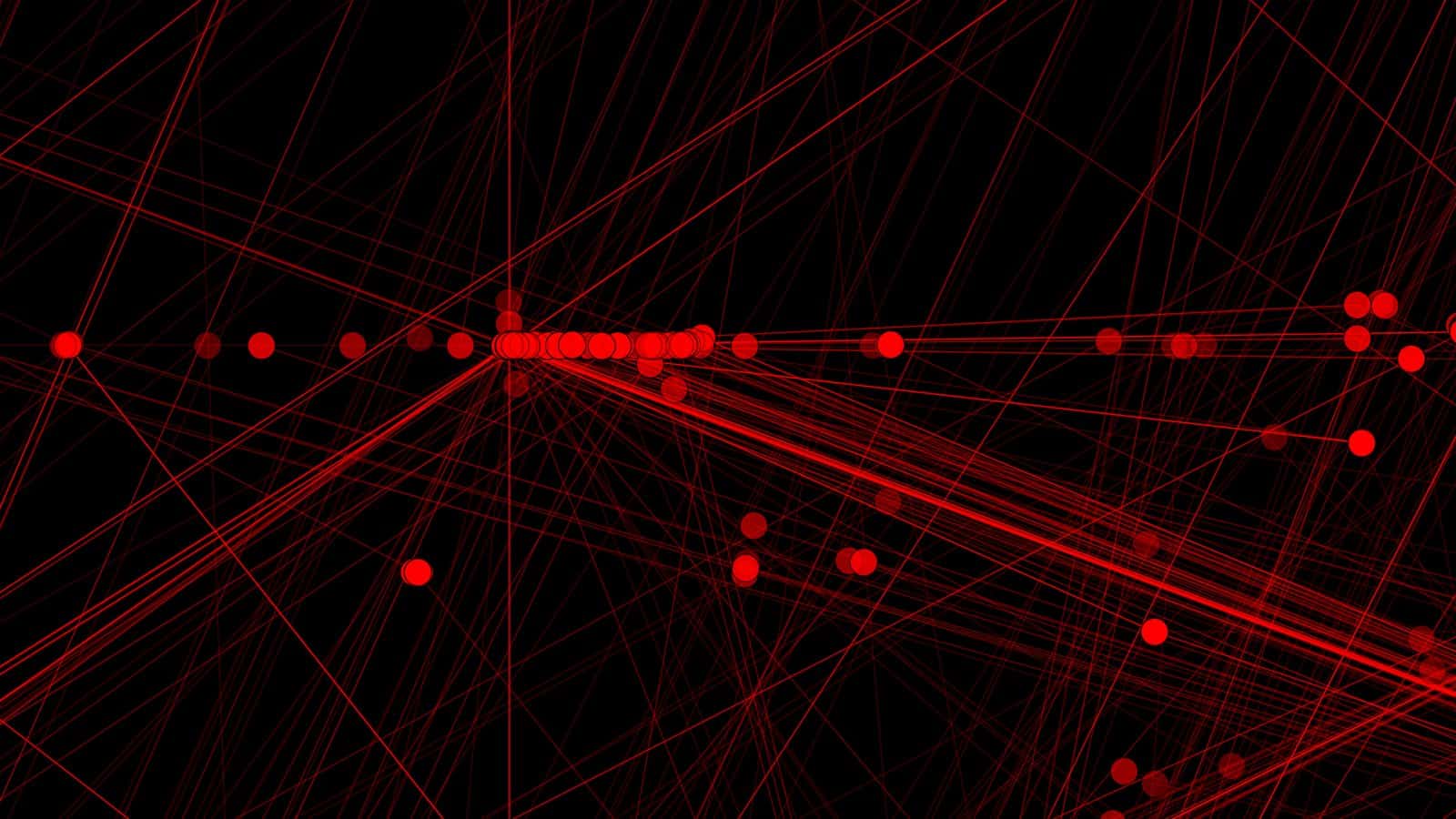

And these plots in the United Arab Emirates:

Such straight lines in data points are common spatial anomalies in built-up urban areas. Studies show that they are indicative of the difficulties of obtaining an accurate signal or location point when the view of the sky is more obstructed, resulting in limited line-of-sight for satellites.

‘Likely real data’

We shared these graphs and similar analysis for the complete dataset with mobile network security expert Gary Miller, and John Scott-Railton, Senior Researcher at the cybersecurity research group Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs.

Both experts separately confirmed that the geographical patterns and the temporal rhythms we identified, including the apparent outliers, are closely consistent with real mobile phone data. They also explained that such a quantity of data points would be extremely difficult to simulate, and also a ‘highly irregular’ practice given industry norms.

The spatial ‘irregularities’ in our sample—a common signature of real mobile location tracks—further support our assessment that this is real data. Therefore, the dataset is most likely not ‘dummy’ nor computer generated data, but rather reflects the movement of actual individuals, possibly acquired from telecommunications carriers or a third-party source.

NSO claims that ‘obfuscated’ user data does not pose privacy risks. However, studies show that even without individual names, the numbers or IP addresses of the mobile devices, with enough space and time coordinates exposed—as in the case of the database we examined—the identity of a person could be uniquely identified and their movements reconstructed.

As Miller explained:

‘…that is a breach of privacy, even if it is anonymized data. Because ultimately you can find out who that person is. Out of a big group of people you can find out who that person is just by looking at their movement patterns.’

This poses privacy risks according to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union—under whose jurisdiction NSO’s exposed database falls. GDPR guidelines identify personal data as any information relating to an identifiable natural person—or data subject—including a name, an identification number, or location data.

Privacy Concerns in a Pandemic

If indeed this is likely real data, then NSO Group has violated the privacy of more than thirty thousand unsuspecting individuals in Rwanda, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates by failing to appropriately protect their private data.

This is troubling because, as a surveillance company with advanced cyber-weapons software, NSO likely has access to private details from infected user devices, beyond simply location data.

While the breach of the Fleming dataset appears in itself to be a violation of private information, this exposure raises a number of other questions which we have passed on to NSO Group:

What are the origins of this mobile phone data?

As a cyber-weapons company based in Israel, how could NSO Group receive access to mobile data from Saudi Arabia with which Israel has no diplomatic relations?

If NSO did have access to this mobile phone data from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and Rwanda could this relate to the reported use of its cyber-weapon software Pegasus in these countries?

As an Israeli company, why might NSO use mobile data from these countries to demonstrate the efficacy of its software to European and North American clients?

And finally, does NSO Group—whose cyber-weapons software Pegasus can access private data from infected user devices—protect the private data to which it may have access in an appropriate manner?

Update

30.12.2020

30.12.2020

Techcrunch report