Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

- Forensic Architecture: Witnesses

- Shaping Space – Architectural Models Revealed

- Forensic Architecture: True to Scale

- Forensic Architecture: Design as Investigation

- Signal or Noise - The Photographic II

- République Géniale

- Counter Investigations

- Forensic Architecture: Hacia una Estética Investigativa

- The Other Architect

- Forensic Architecture: Towards an Investigative Aesthetics

- Burden of Proof

- Forensic Architecture at Venice Architecture Biennale 2016

- The Urban-Data Complex at Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture 2015

- La Fin Des Cartes

- The Other Architect

- Social Glitch

- Forensis

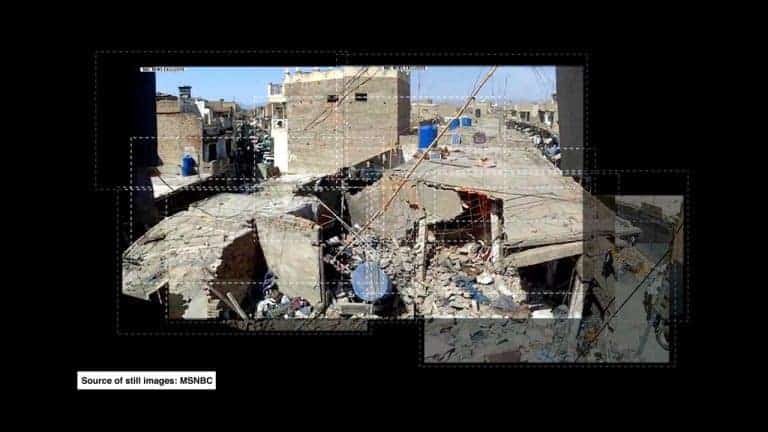

Footage of the aftermath of drone strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) rarely makes it out of the region. In the case of a March 2012 strike in Miranshah, North Waziristan, however, it did: a video of the scene of the strike was physically smuggled through military cordons before it reached employees of US news network MSNBC. The network aired footage from the scene of the strike on 22 June 2012.

The video, likely recorded on a mobile phone, was composed of two sequences that documented different parts of a ruined building.

The first sequence was shot from a window opening on the third floor of the building; out of the window, the damaged roof of a lower building is visible, located in a dense market street and surrounded by what appear to be residential and commercial buildings.

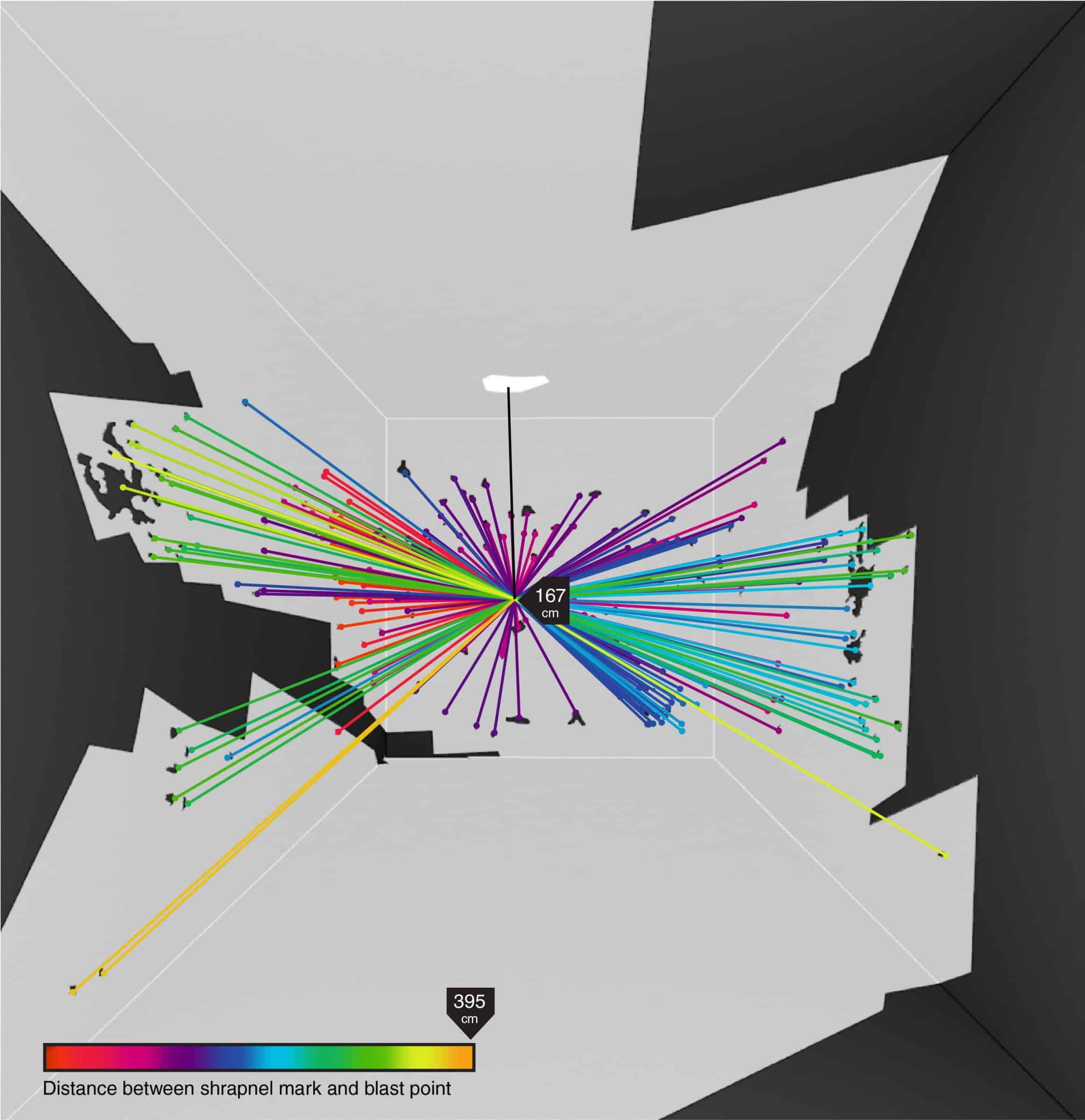

The second sequence showed the interior of a room inside the damaged building. A hole in the ceiling marked the point of entry for the missile. The walls were scarred by hundreds of blast marks, caused by shrapnel from the missile’s fragmentation sleeve.

Each fragment hit the wall at a different angle. Using the information inscribed in those impact marks, Forensic Architecture (FA) deduced the precise location within the room at which the missile had detonated.

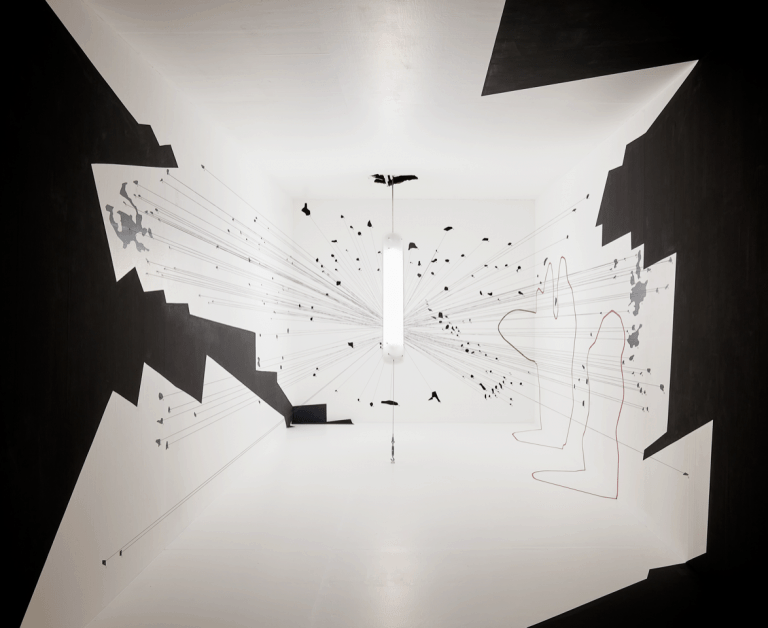

The blast occurred in midair, confirming the munition was a delay-fuse missile, likely a ‘Romeo’ Hellfire II AGM-114R. In two areas, the walls contained no scarring. If there had been people in the room when the missile exploded, their bodies would have absorbed the fragments and stopped them from reaching the wall.

In this way, the wall functioned as a photographic film, and the figure of the blast’s victims was recorded on the wall, similar to the way in which a photographic negative is exposed to light. Through a process of ‘double photography’—the video stills of the room were, in effect, photographs of a photograph—the human bodies destroyed by the drone strike were made present.

Methodology

Methodology

The video’s first sequence tells about the videographer; its second tells us something of the people killed by the strike.

Theorist Ariella Azoulay urges us to study the circumstances by which images are produced, broadcast, viewed, and acted upon, and to follow the set of relations that the photograph establishes between the photographer and the spaces and subjects photographed. In this case, such relations also extended to the people who carried the footage out of the area, those who broadcast it, those looking at it, and those, like us, modelling and helping to decode it.

Cameras record on both sides of the lens: the objects, people, and spaces they capture, and the position and movement of the invisible photographer. Blurs, for example, are important in revealing things about the photographer. Rushed and erratic camera movements might indicate the risk involved in taking some images. A blur is thus the way the photographer registers within an image. Looking at blurry images is like looking at a scene through a semi-transparent glass in which the image of the photographer is superimposed over the thing being photographed.

Similarly, the concrete window opening captured in the video’s first sequence may have recorded the videographer’s sense of a danger perceived to come from outside. It might be that the videographer feared being seen filming by locals, or by drones overhead. Drones sometimes strike the same spot twice, a process known as ‘double tap’.