Commissioned By

- Lawyers for the Moria 6

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

In the late hours of 8 September 2020, large fires broke out at the migrant camp of Moria, located on the frontier island of Lesvos, Greece. The fires smouldered over several days, displacing thousands of people and reducing the epicentre of the EU’s carceral archipelago to ashes. The overcrowded camp, first established in 2013, was host to more than 13,000 people at the time, and was notorious for its precarious and unsafe living conditions—conditions manufactured and maintained for years by Greek and EU policies.

Only a few days after the fire, and before the local Fire Service had concluded their investigation, police arrested six young asylum seekers, five of them minors, accusing them of starting the fire. They later became known as the ‘Moria 6’. On the same day that the Moria 6 were arrested, the Greek Minister of Migration and Asylum publicly declared that ‘the arsonists of Moria have been detained [and] the safety of everyone is guaranteed’. The speed of his announcement following the arrests raised serious questions as to whether the trials that followed would be conducted fairly.

Indeed, two subsequent trials that resulted in conviction, one for the two recognised as minors, and the other for the remaining four, were strongly criticised for failing to offer fair proceedings to the accused and described as a ‘parody of justice’. Five of the Moria 6 were convicted on the testimony of a single witness, reportedly the leader of a rival ethnic community in the camp. Greek authorities failed to even bring him to court to stand as a witness.

FA/Forensis were commissioned by the lawyers representing the Moria 6 to map how the fire developed on 8 September 2020 and to interrogate the testimony of the key witness, in advance of the appeal trial of the accused group of four scheduled for March 2023. We sourced and examined hundreds of videos, images, testimonies, and official reports, and conducted a detailed spatio-temporal reconstruction of the spread of the fire through the camp. Our analysis reveals significant inconsistencies in the testimony of the key witness and casts further doubt on the evidence upon which the judgment of the young asylum seekers was based.

Update

08.03.2023

08.03.2023

Dimitra Andritsou, researcher-in-charge, travelled to Lesvos to appear as a witness in the appeal trial of 4 of the Moria 6, scheduled to take place in Mytilene on 6 March 2023. After an initial delay of two days, the appeal hearing was postponed until 4 March 2024 by the Lesvos court. The 4 will likely remain incarcerated for another year, despite no credible evidence, & procedural errors.

Read more about the proceedings and their implication in this post by Legal Center Lesvos.

Update

08.03.2024

08.03.2024

The appeal hearing of 4 of the Moria 6 took place between 6-8 March 2024, after a delay of one year. The hearing followed the trial on first degree that took place behind closed doors in 2021 and was widely characterised as ‘parody of justice’.

Structural racism dominated the appeal trial, eroding the alienable right to a fair trial.

The defence team invited FA/Forensis to contribute to the trial in an expert capacity. Our investigative video and report could have contributed significantly to the understanding of how the fire spread – however, the presiding judge and prosecutor rejected both the video and the report as “irrelevant to the case”. Additionally, Dimitra Andritsou, researcher-in-charge of the investigation who was called to testify as expert witness, was met with disparaging, dismissive, and obstructive treatment by the presiding judge and prosecutor. Constant interruptions and provocative questions distracted from the crucial function of the trial: to present critical evidence so that the court could draw accurate conclusions about the event in question.

The appeal hearing resulted in the conviction of one of the four defendants, confirming what was known all along: that the inhumane management of the camp by Greece and the EU required a scapegoat, for a disaster that was designed to happen.

On a more positive development, the three other defendants scheduled to appear before court had their prior conviction cancelled and have been released on conditions after three and a half years imprisonment, after the court accepted the objection brought forward by the defence lawyers regarding the fact that they were minors as the time of the fire, and assessed that they were convicted in error by an incompetent court at first instance.

Read more about the trial in this press release by Legal Centre Lesvos.

Read coverage of the proceedings in Greek and in English as monitored by Moria Trial Watch, an joint initiative between OmniaTV and Solomon with the support of Rosa Luxemburg Foundation–Office in Greece.

Methodology

Methodology

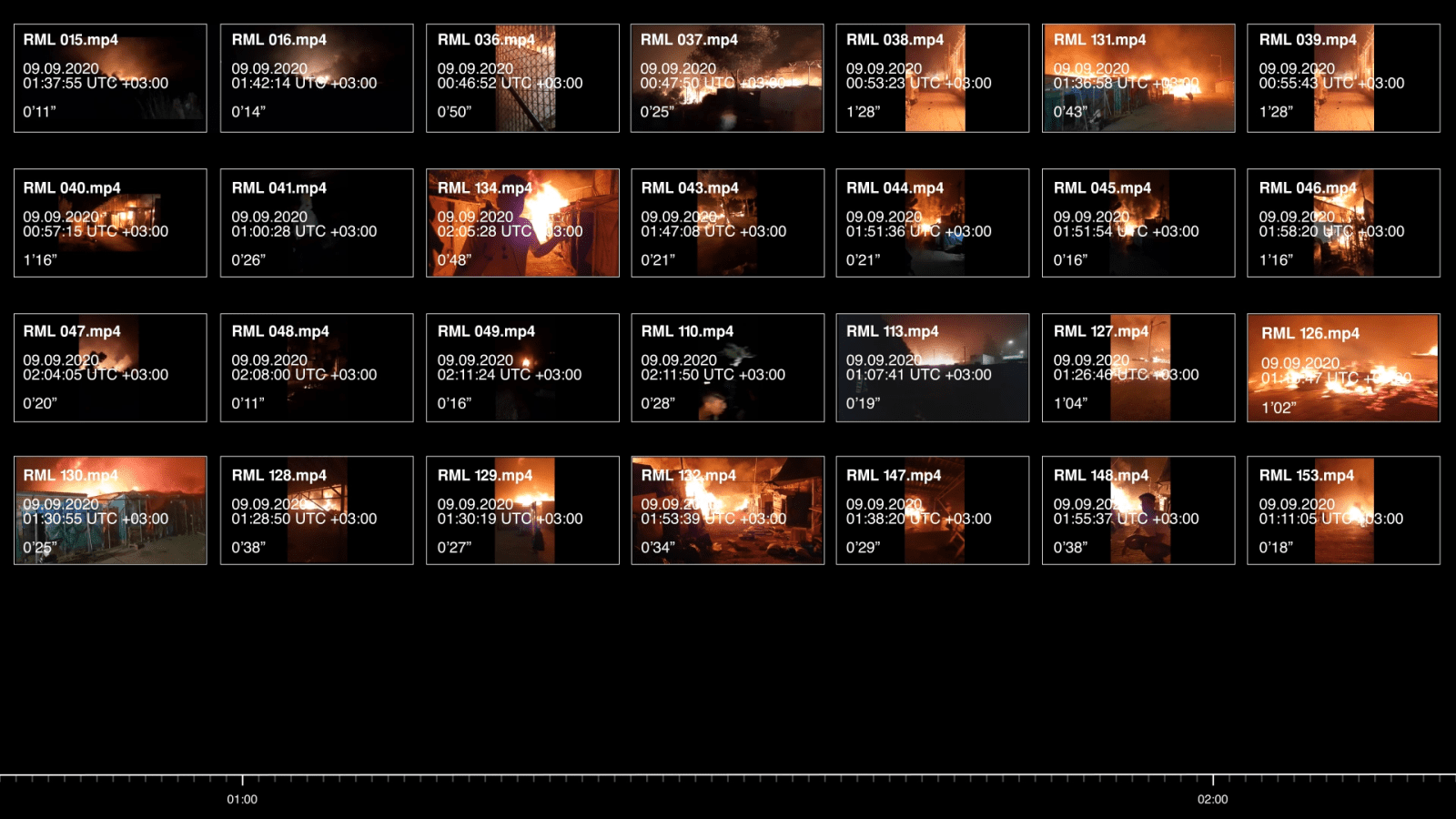

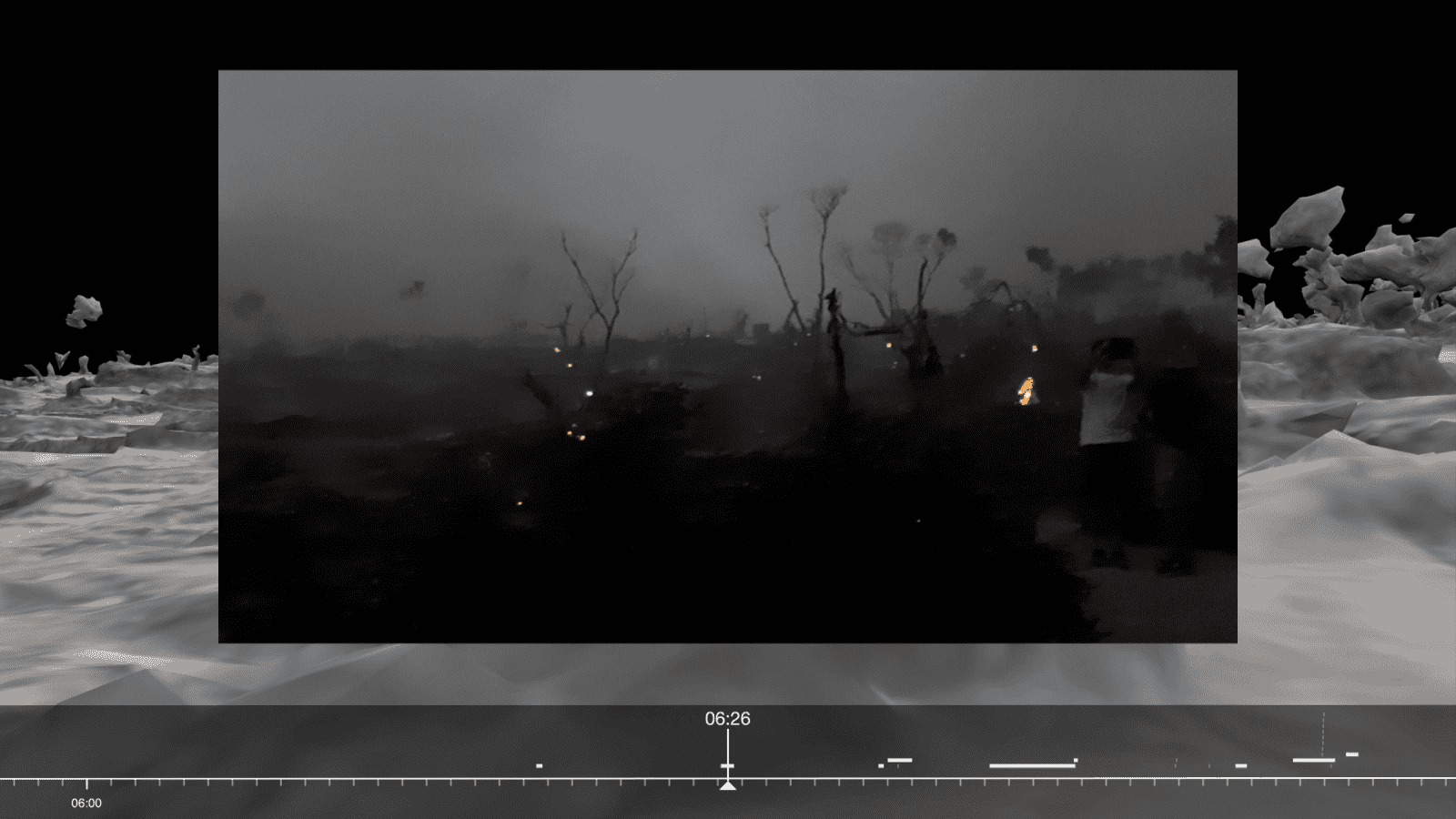

Α large part of the audiovisual material that was analysed consisted of footage shot by young migrants, students of ReFOCUS Media Labs, an organisation training refugees on Lesvos in filmmaking and reporting. We extracted the times encoded in the metadata of that footage, and cross-referenced that data with additional open-source imagery to create a video timeline of the night.

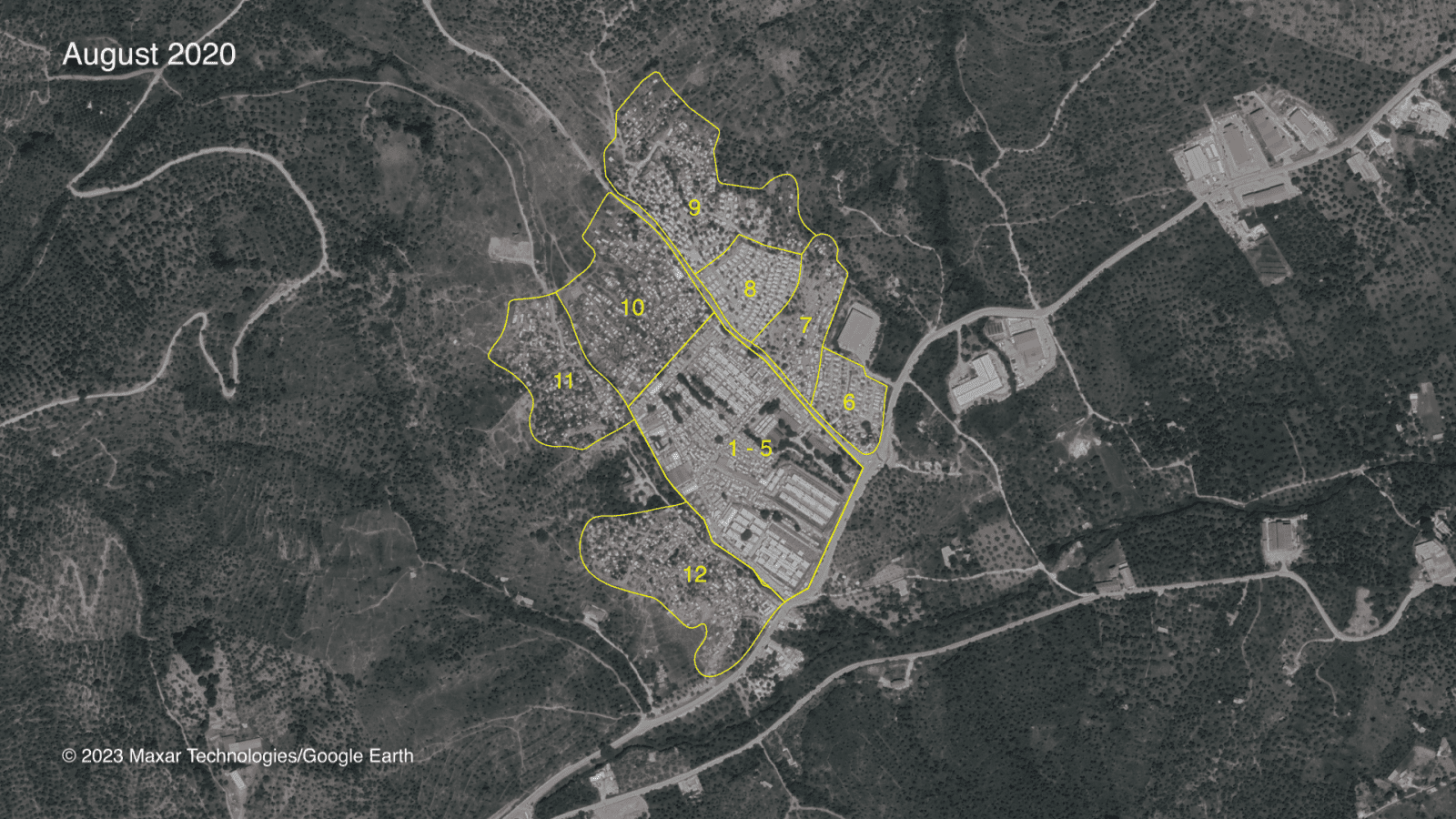

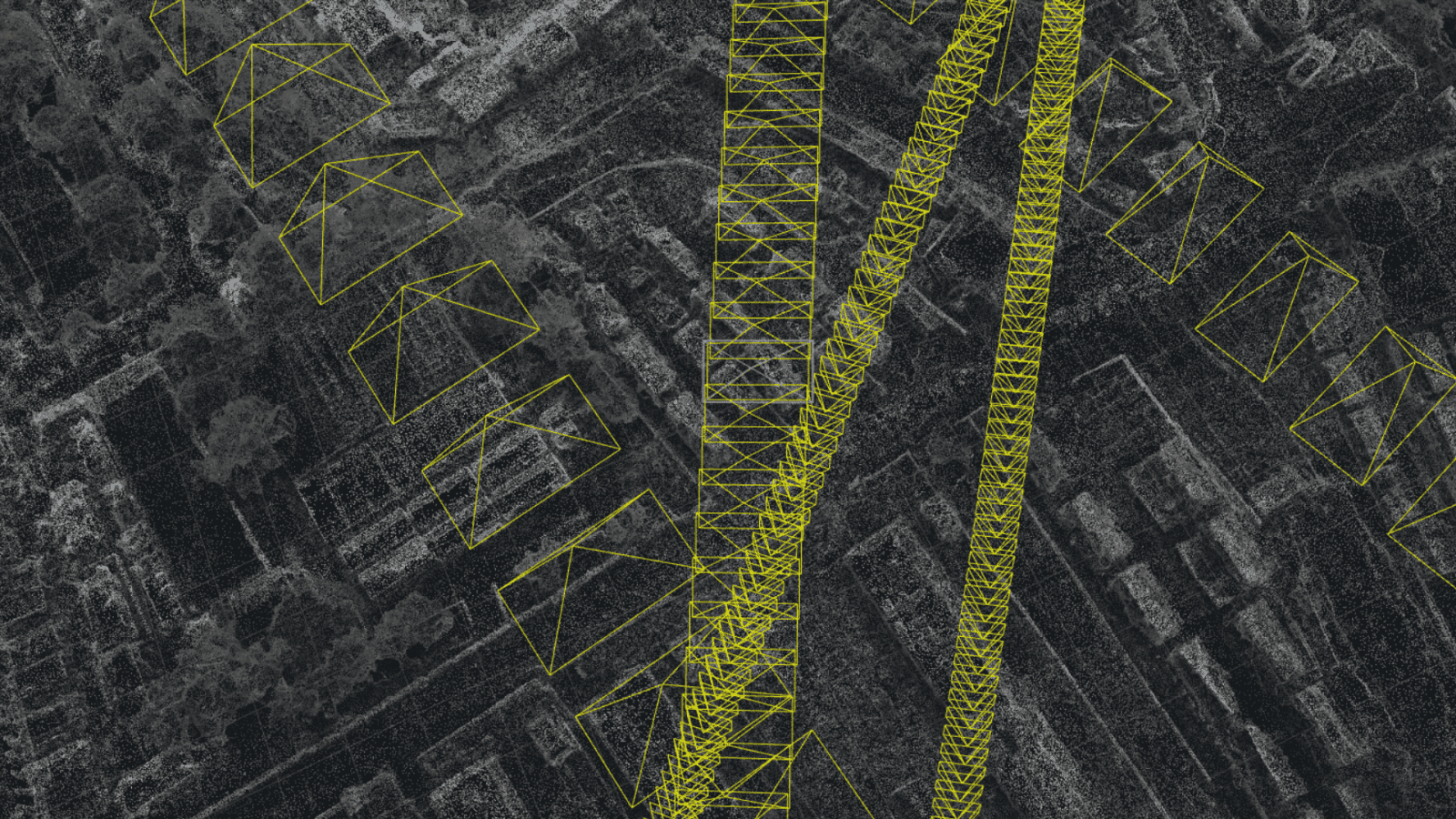

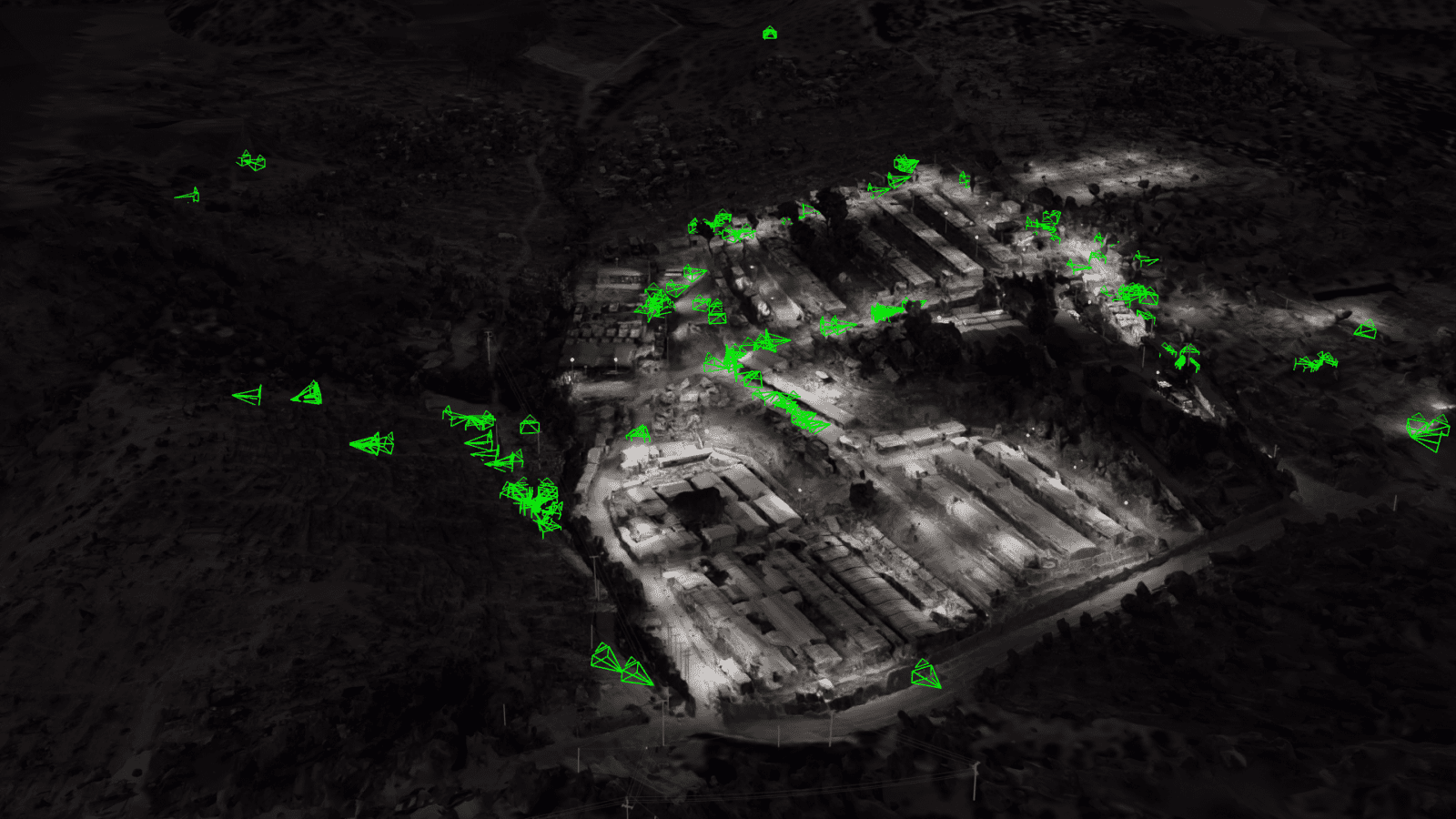

To locate the material in space, we obtained high-resolution drone footage that captured the camp both in early 2020, at the peak of its expansion, and in October 2020, one month after its destruction. Using photogrammetry, we converted the drone footage into navigable 3D models, which represented the state of the camp before and after the fire.

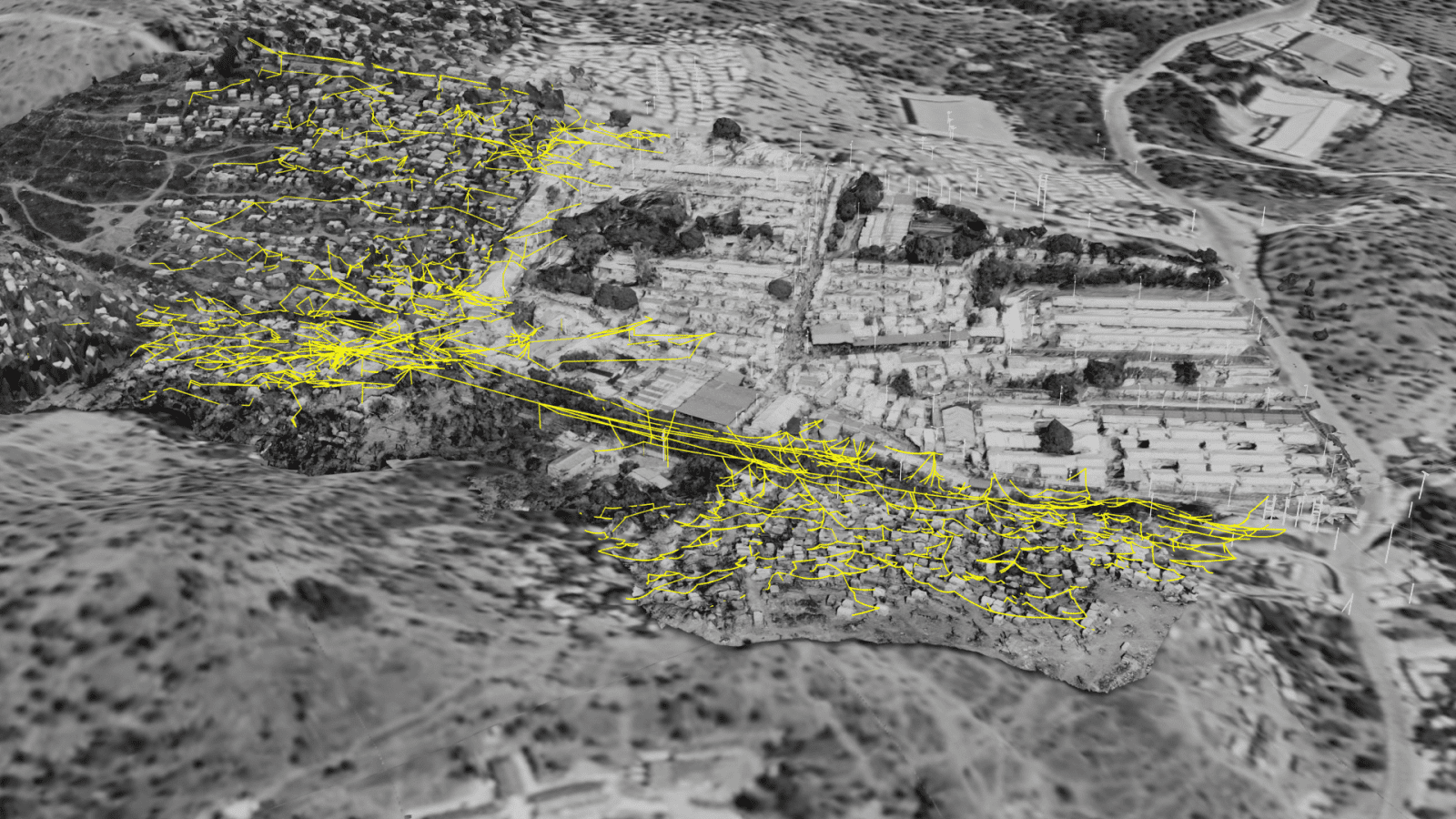

Drone and ground-level footage allowed us to precisely model significant elements, such as the main electrical infrastructure, and parts of the complex grid of ad-hoc electrical wiring in the overspill camp—a network of wires, plugs, sockets, and flimsy connections built by migrants themselves, to compensate for the camp’s inadequate electricity supply.

Understanding this infrastructure also allowed us to accurately simulate the lighting conditions the night of the fire. Together with environmental features such as the terrain’s topography, this infrastructure functioned as a series of visual markers allowing us to accurately locate multiple images and videos within our 3D model, and to determine the relations between them.

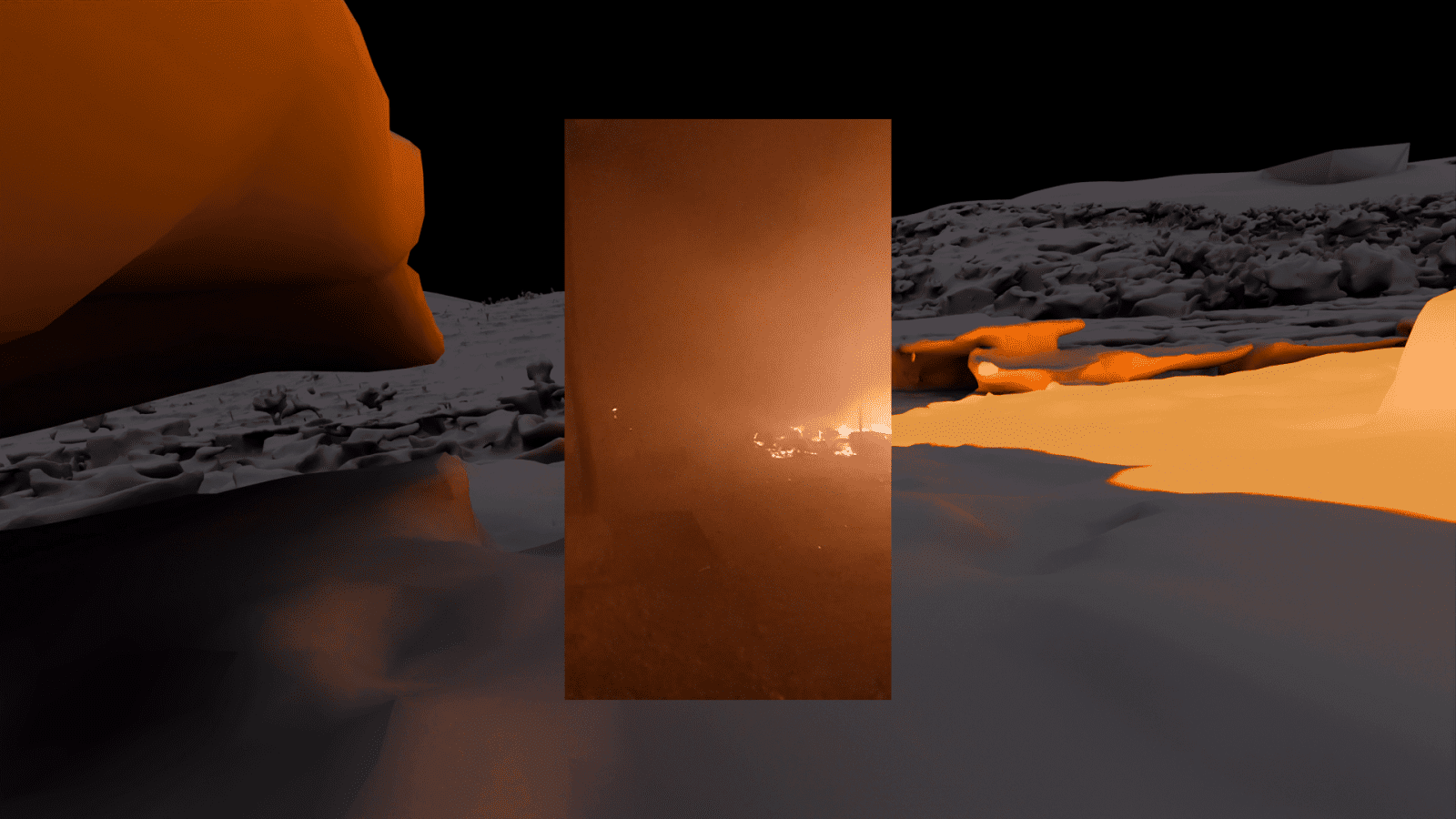

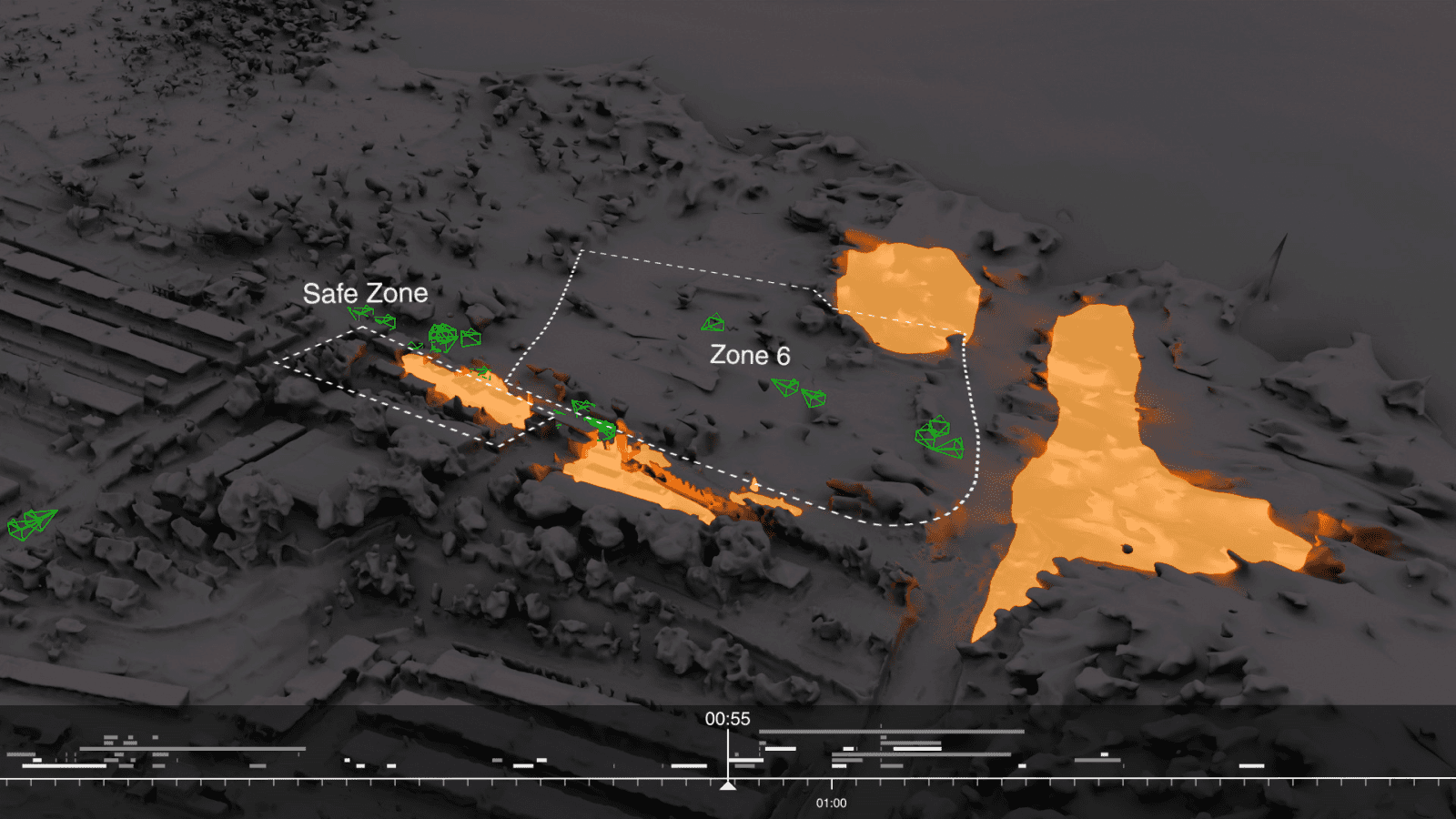

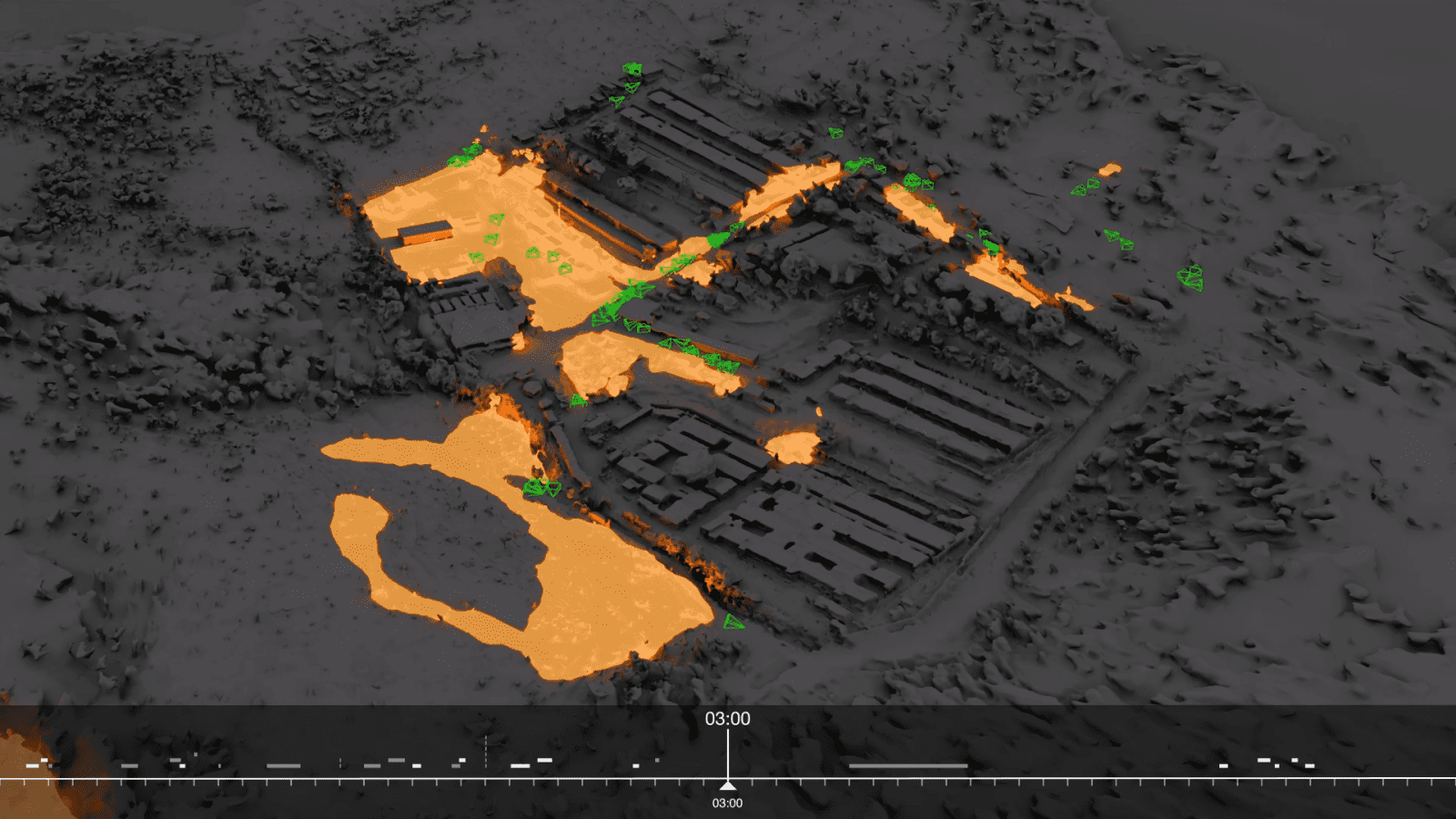

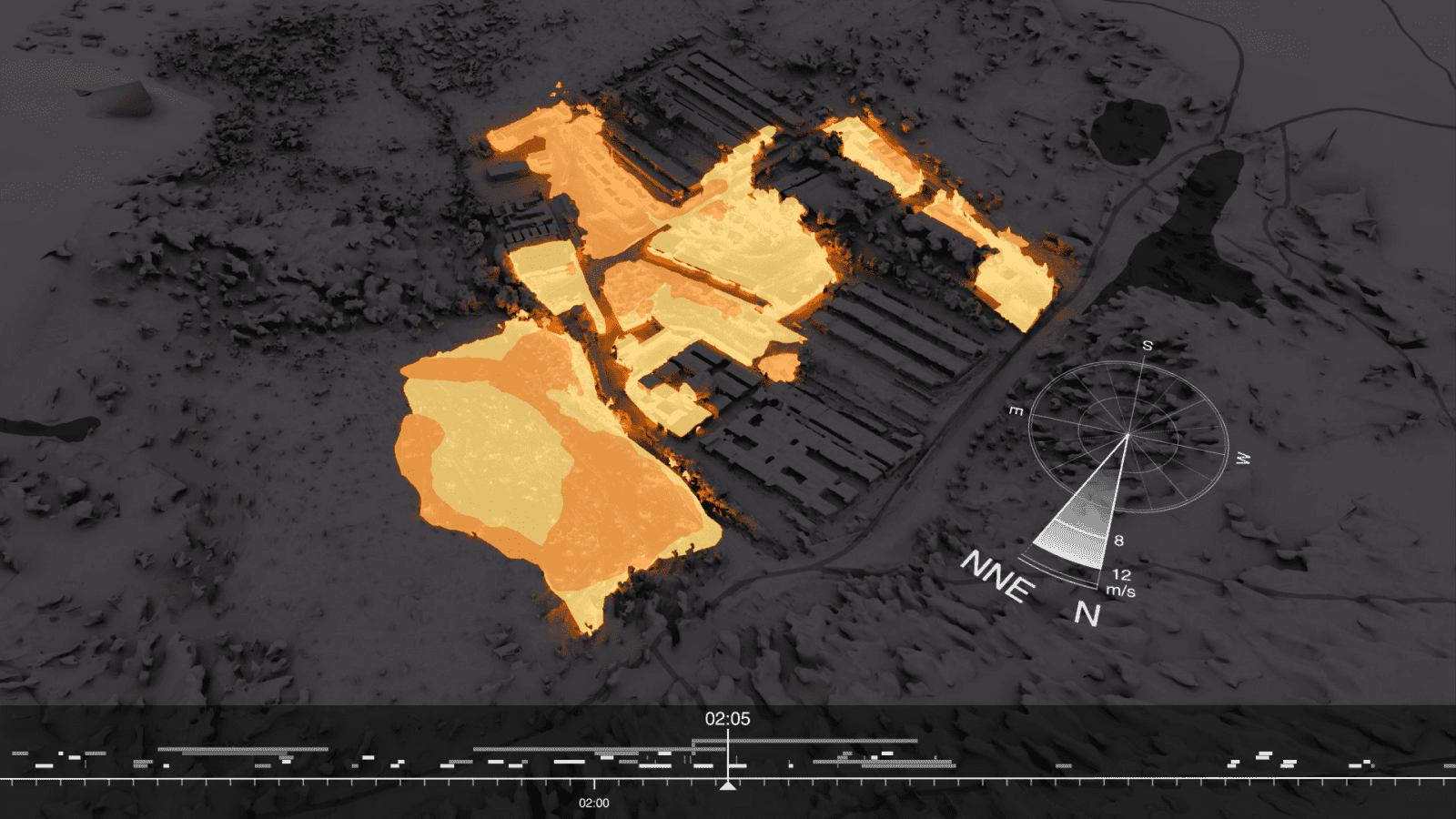

Once all sourced videos were accurately timed and positioned within the 3D model, we marked in orange the areas that we could see burning in the available video evidence.

The Spread of Fire

The first video to capture fire in the immediate vicinity of the camp, specifically in the area bordering Zone 6, was shot at the latest at 11:36pm from the neighbouring town of Moria.

By sixteen minutes past midnight, the fire in Zone 6 had expanded within the camp, near and into an area known as the ‘Safe Zone’, a separate, fenced-off section of the camp where unaccompanied minors resided.

Footage shot at around 1:00am shows that the fire had by this time grown significantly and spread within a densely built area at the centre of the camp composed of makeshift wooden structures and plastic tarpaulin covers.

Strong winds, blowing at an average of 8 metres per second and with gusts up to 12, caused the fire to spread rapidly across the flammable and tightly packed structures.

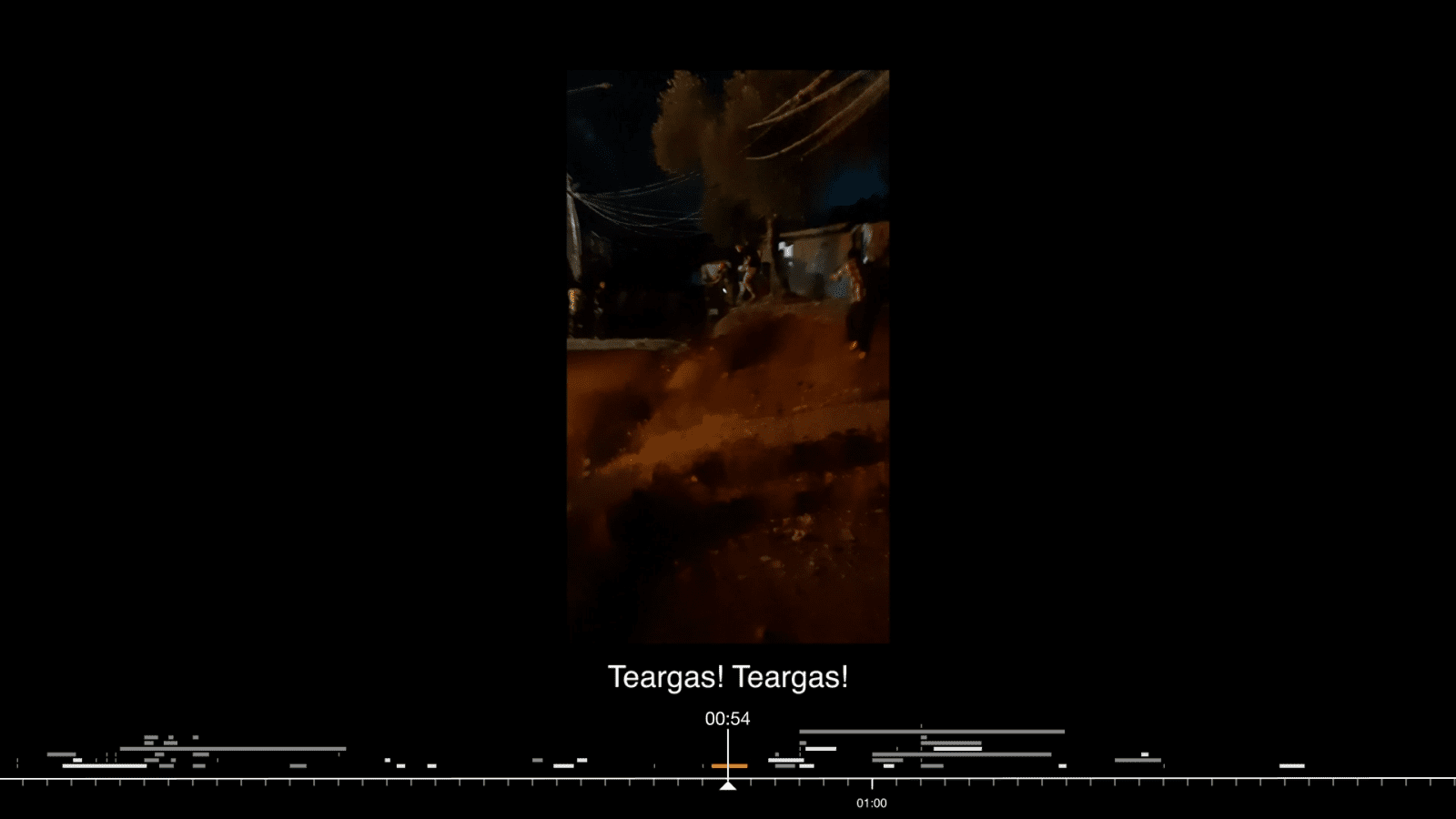

As flames progressively engulfed different parts of the camp, people began trying to flee. Instead of offering assistance, they attacked the fleeing and protesting crowd with tear gas, compounding the already suffocating quality of the atmosphere with additional toxic chemicals.

By 3:00am, most of the camp was ablaze, and more and more people were trying to reach a place of safety. Altercations were reported between migrants and locals in the neighbouring village of Moria, with residents attempting to prevent the fleeing migrants from passing through. Police also set up roadblocks along the road leading to the town of Mytilene to prevent migrants from being able to reach it.

The fires smouldered until the early hours of 9 September, when documentation became more sporadic as most people had fled the area.

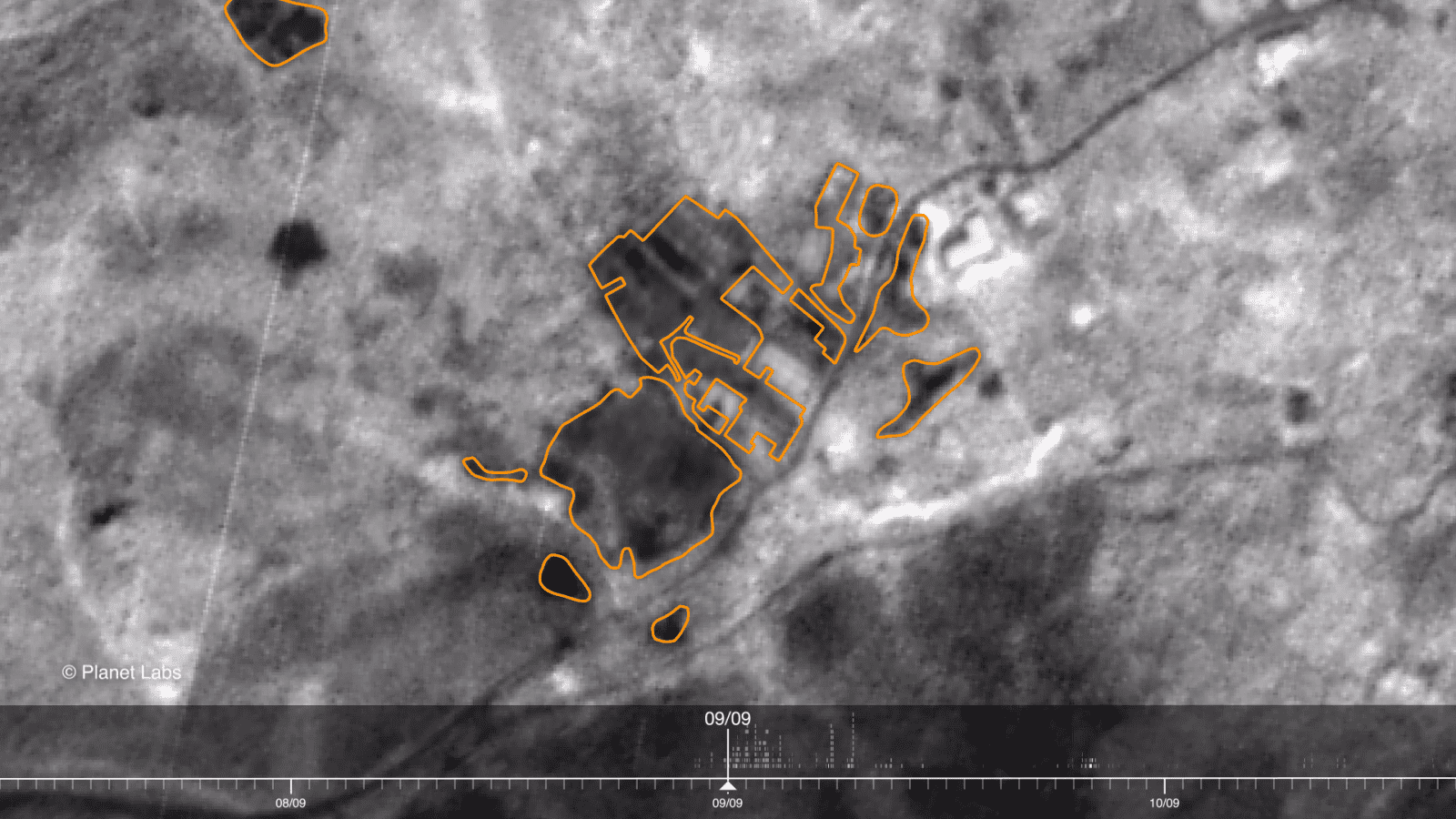

We used remote sensing techniques to track the full extent of the fire damage to the areas that burned that night. The location and extent of the burn ‘scars’ corroborate our mapping of the fire outbreaks and spread as recorded in the footage we sourced. Referencing our diagram of the fire’s movement within the camp, we interrogated the key witness’s statement, on the basis of which the young asylum seekers had been convicted.

Examination of Key Witness Testimony

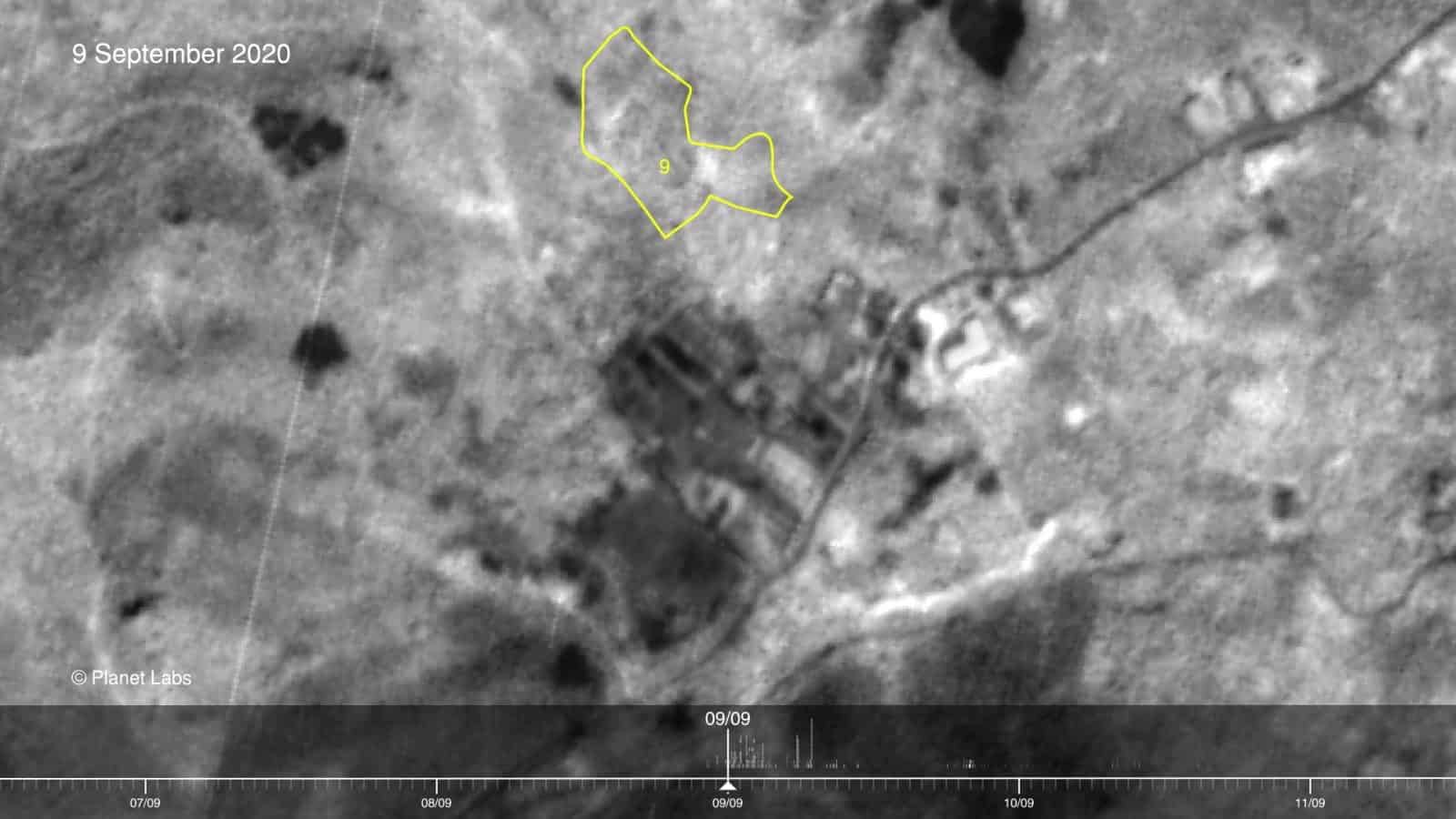

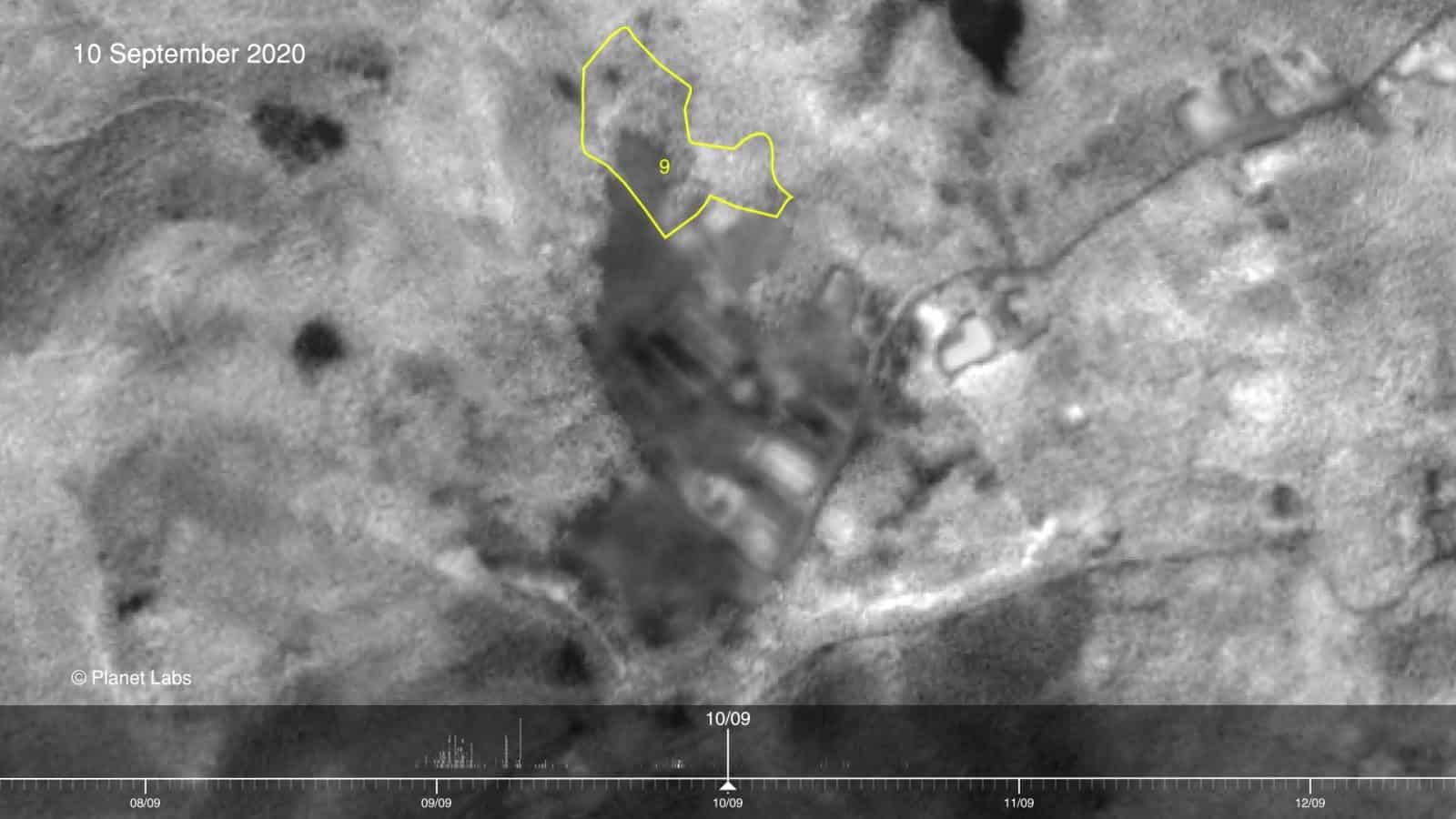

According to his statement, on the night of 8 September the key witness was outside his tent in Zone 12 when he saw a large fire burning through the area of the ‘Dutch’—a reference to the nationality of the aid workers in that part of the camp—which is identified as Zone 9. Analysis of satellite imagery shows, however, that contrary to this claim, Zone 9 did not catch fire that night.

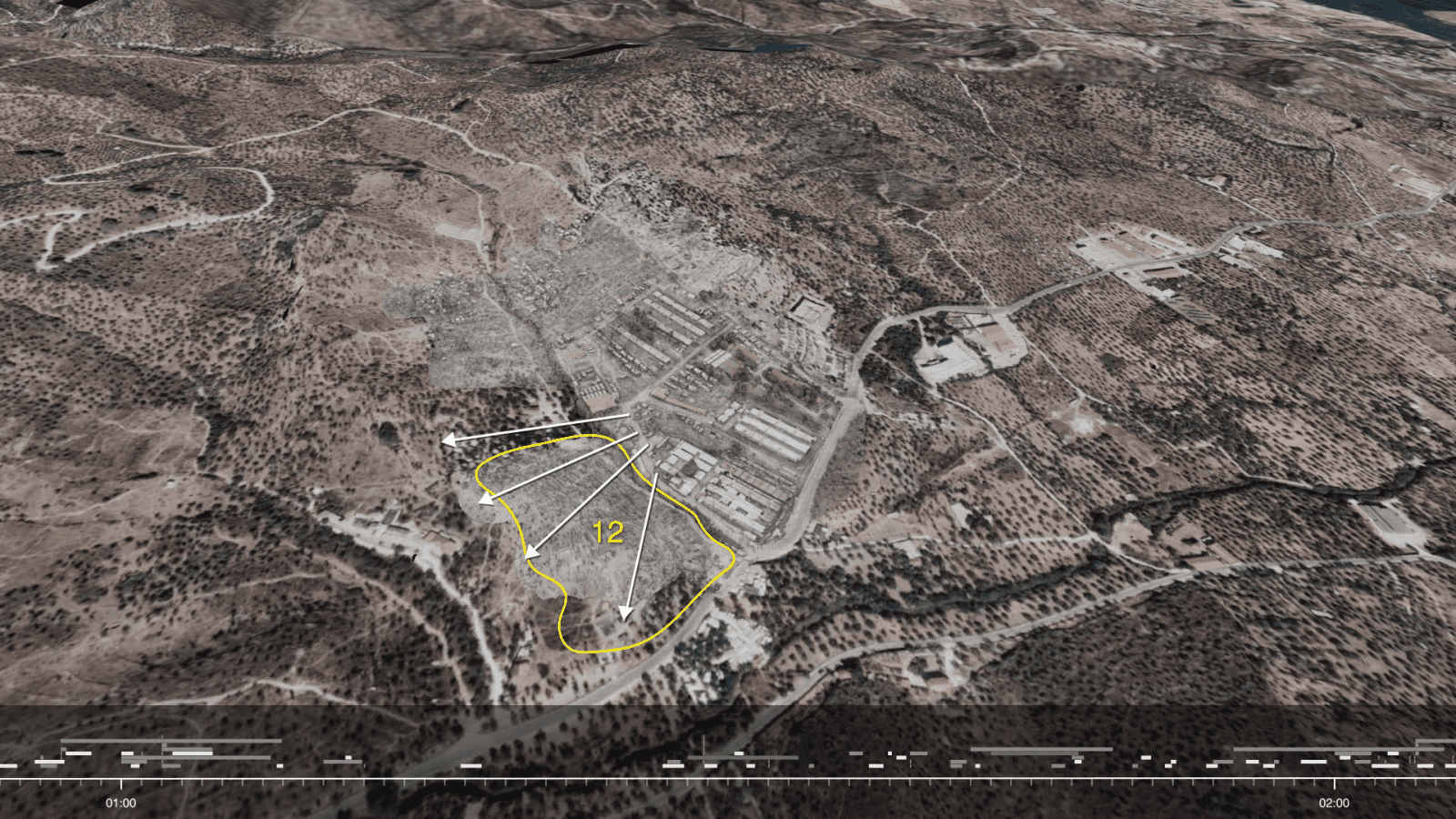

A few minutes after supposedly seeing Zone 9 on fire, the witness remembers noticing smoke and flames near his tent, and then ‘everywhere in Zone 12’, without mentioning the large fires that had already reduced most of the rest of the camp to ashes. We photomatched images taken from various locations in Zone 12 that night, demonstrating that it would have been impossible for the witness to miss the high flames burning through the centre of the camp long before Zone 12 caught fire.

The witness’ testimony is also contradicted by the official autopsy report of the local Fire Service, stating that Zone 12 was burned by fires spreading from the centre of the camp, due to the strong prevailing winds. Our analysis of the progression of the fire in that part of the camp, and further consultation with fire experts, corroborates the report, mapping a pattern of fire spread that is consistent with the wind direction that night, rather than arson.

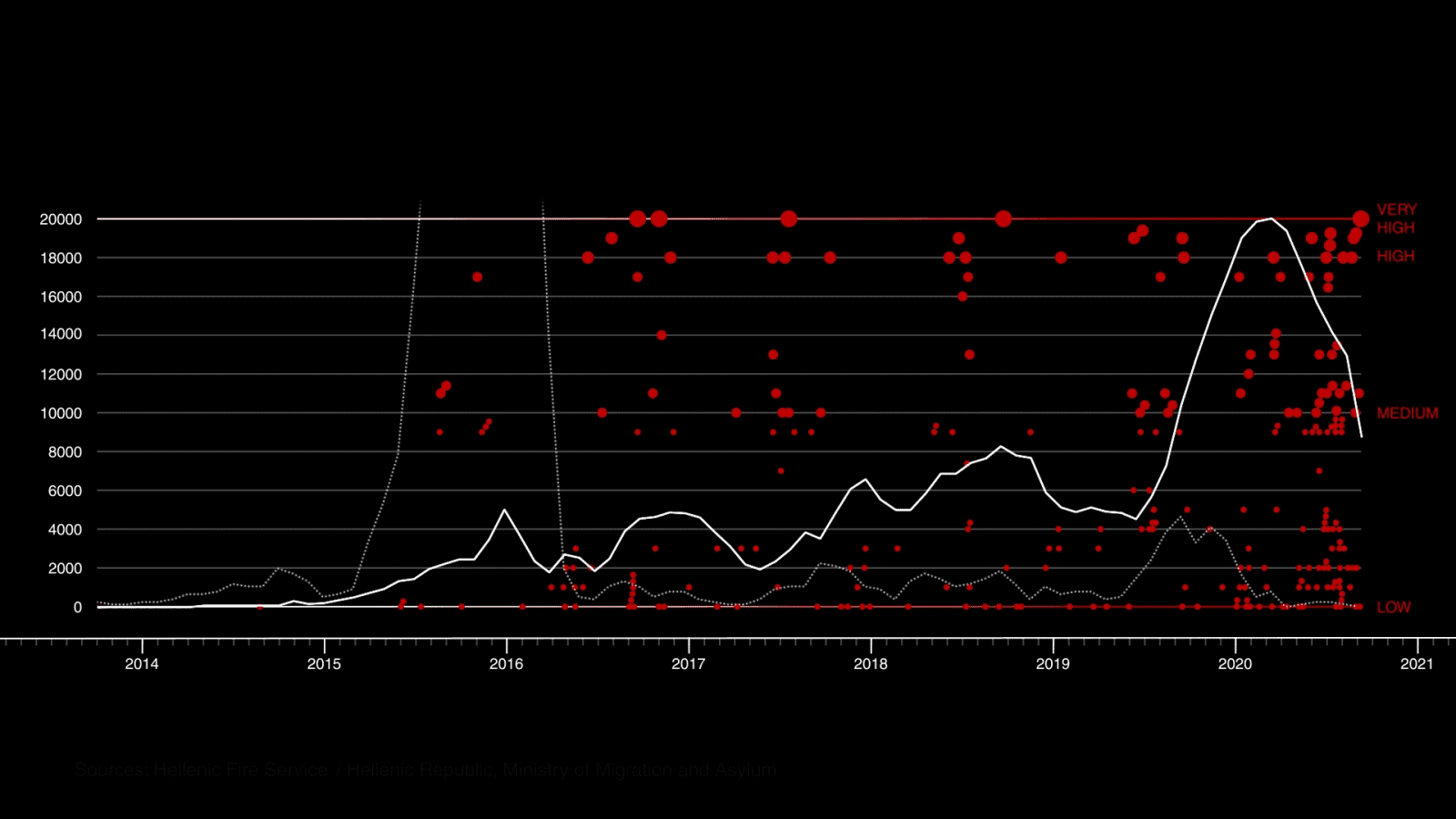

247 Fires

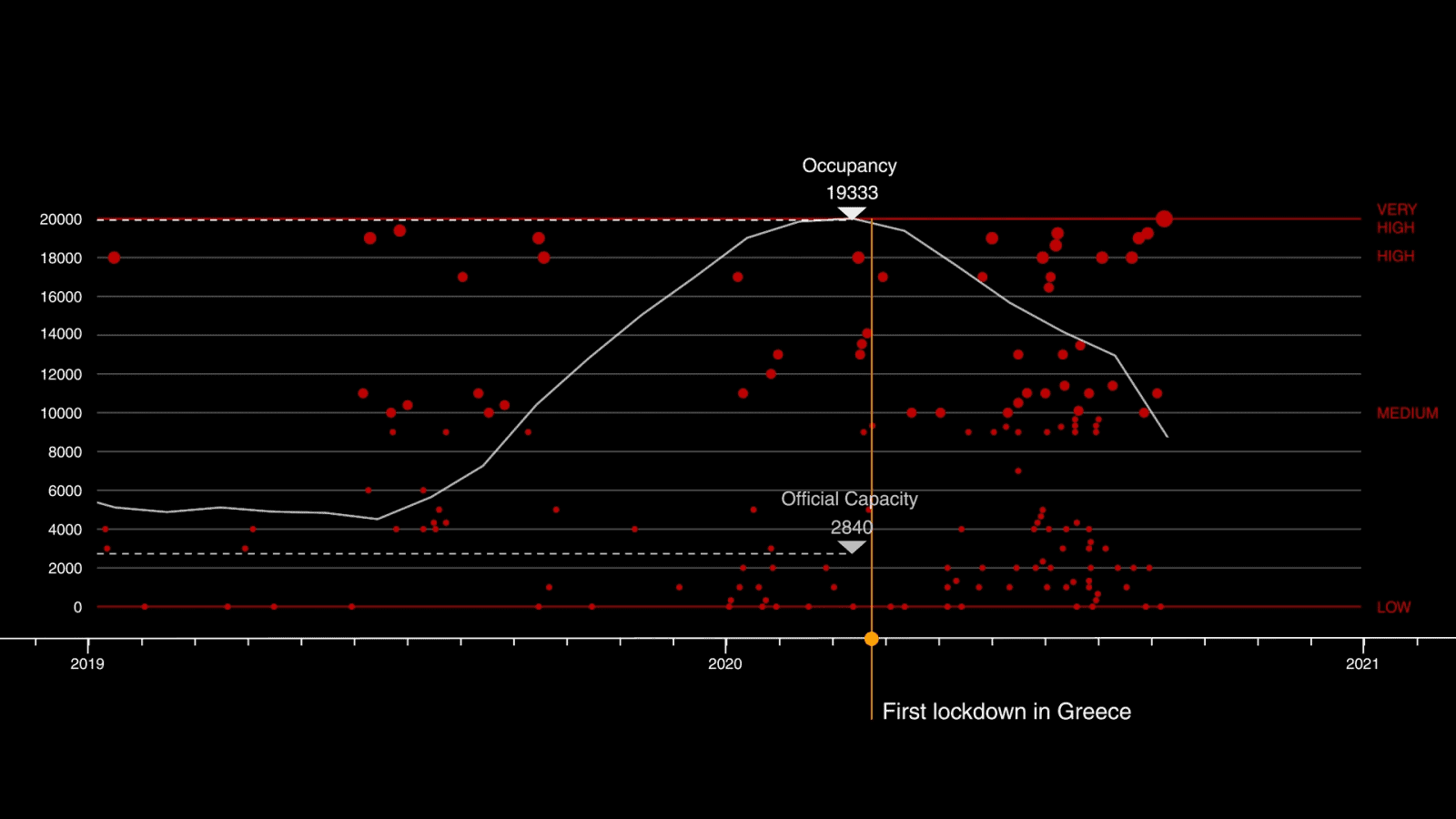

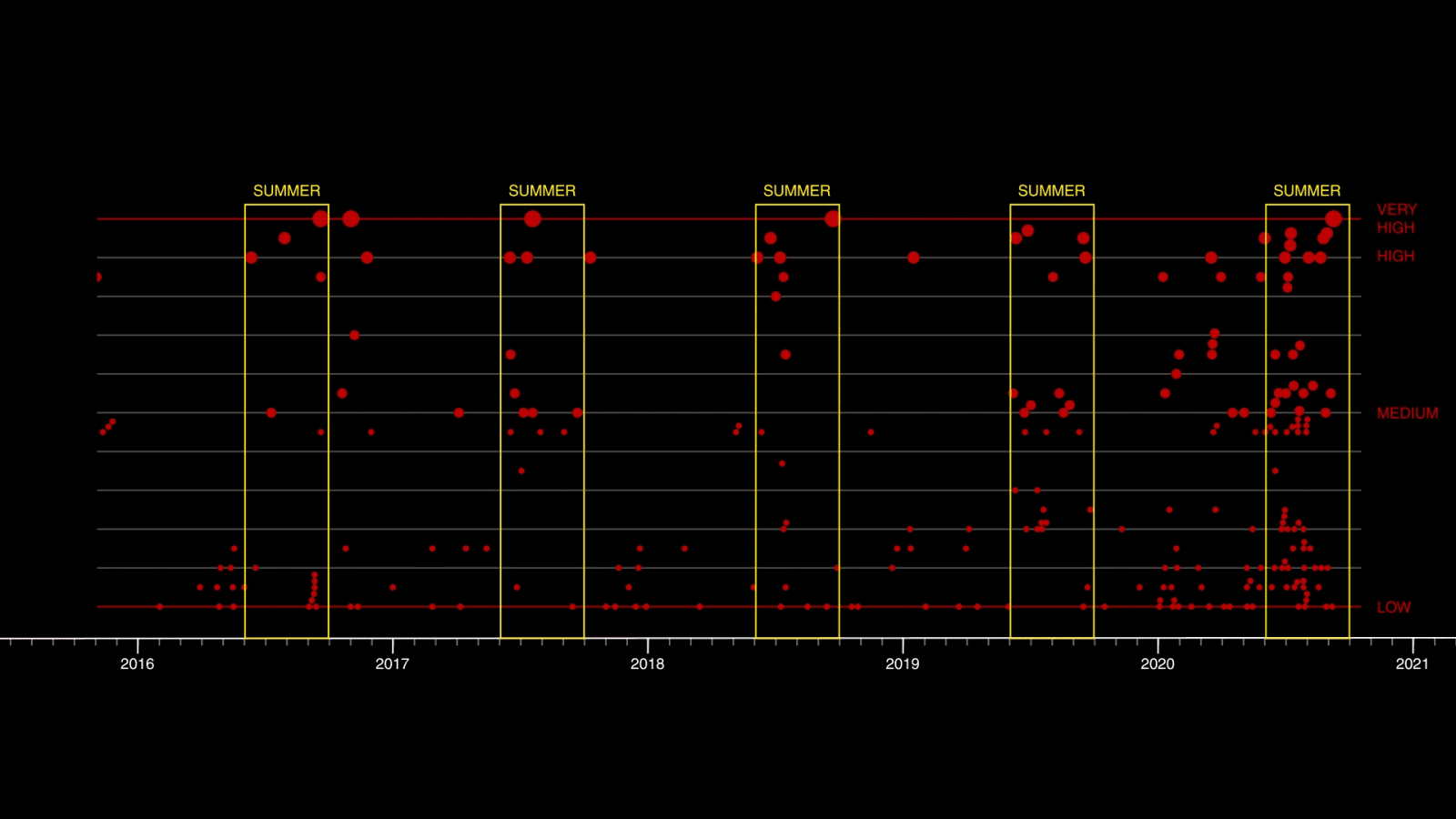

The fire of the 8 September 2020 was the last in a series of at least 247 recorded outbreaks in and around the camp since its establishment in 2013. The camp’s population began to grow significantly after restrictions on movement were imposed in March 2016, even though EU policies of exclusion led to lower levels of arrivals than in previous years. As the camp became increasingly overcrowded, the frequency of fires, as well as their size and intensity, continued to rise.

In early 2020, during the first wave of the Covid pandemic and only a few months before Moria burned to the ground, the camp’s population peaked at nearly 20,000 people—close to seven times its official capacity. Almost half of the recorded outbreaks, at least 112, occurred in the first nine months of 2020 alone.

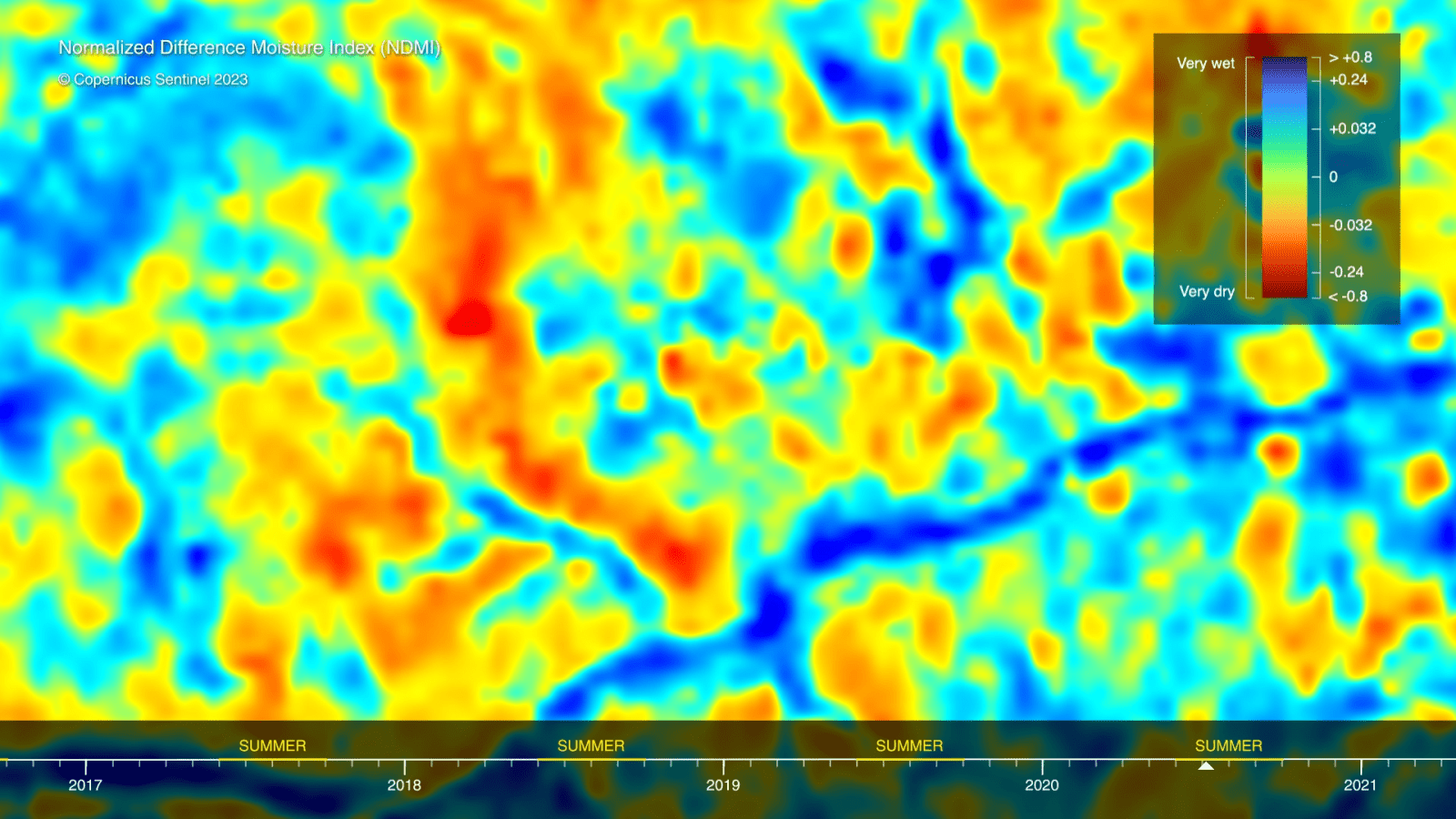

Recurring fires in the camp were the result of shifting carceral policies amidst a warming climate. September—late summer—is when the ground is driest in this Mediterranean region. Dry conditions, combined with the precarity and density resulting from policies imposed by Greek and EU authorities, led to a steep increase in large fires every year around this time.

Despite this ever-present risk, no safety measures were put in place to mitigate the dangers posed by these compounding forces. Viewed in light of this recurring pattern of fire, neither the September 2020 blaze which destroyed the camp, nor any of those in which lives were lost in previous years, were isolated incidents.

Rather, they were symptoms and material manifestations of intersecting phenomena: chronic overcrowding, problematic EU and state policies, enforced precarity, failing humanitarian infrastructure, prolonged droughts and heatwaves, and, most recently, deepening inequalities driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our analysis of the September 2020 fire shows that the judgment against the young asylum seekers was based on weak and contradictory evidence, and suggests that the inhumane management of the camp by Greece and the EU required a scapegoat for what was effectively a ‘disaster by design’.