In Partnership With

Additional Funding

- Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

- Open Society Foundations (OSF)

Collaborators

- Alarm Phone

- Border Violence Monitoring Network

- Greek Council for Refugees

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

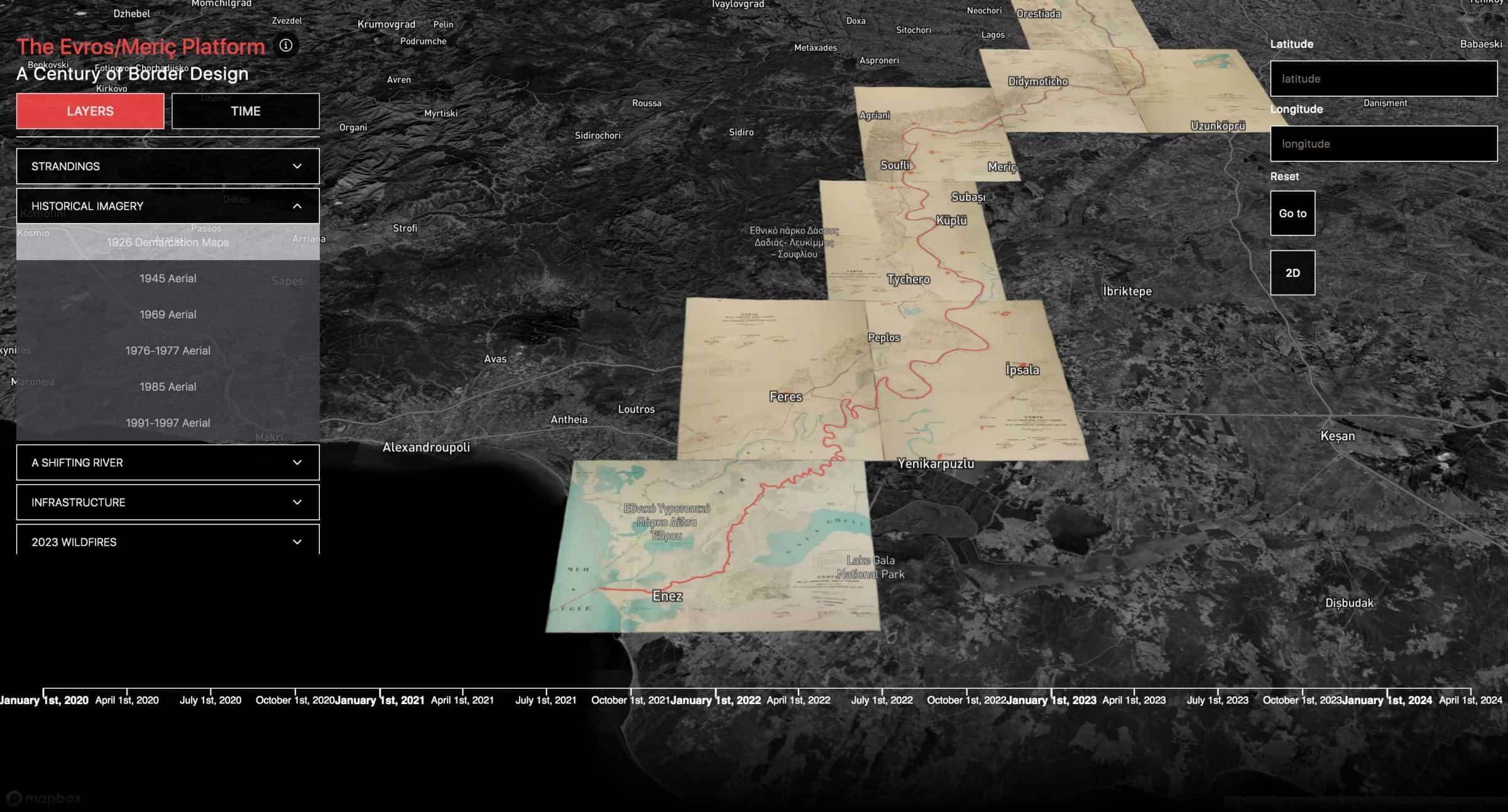

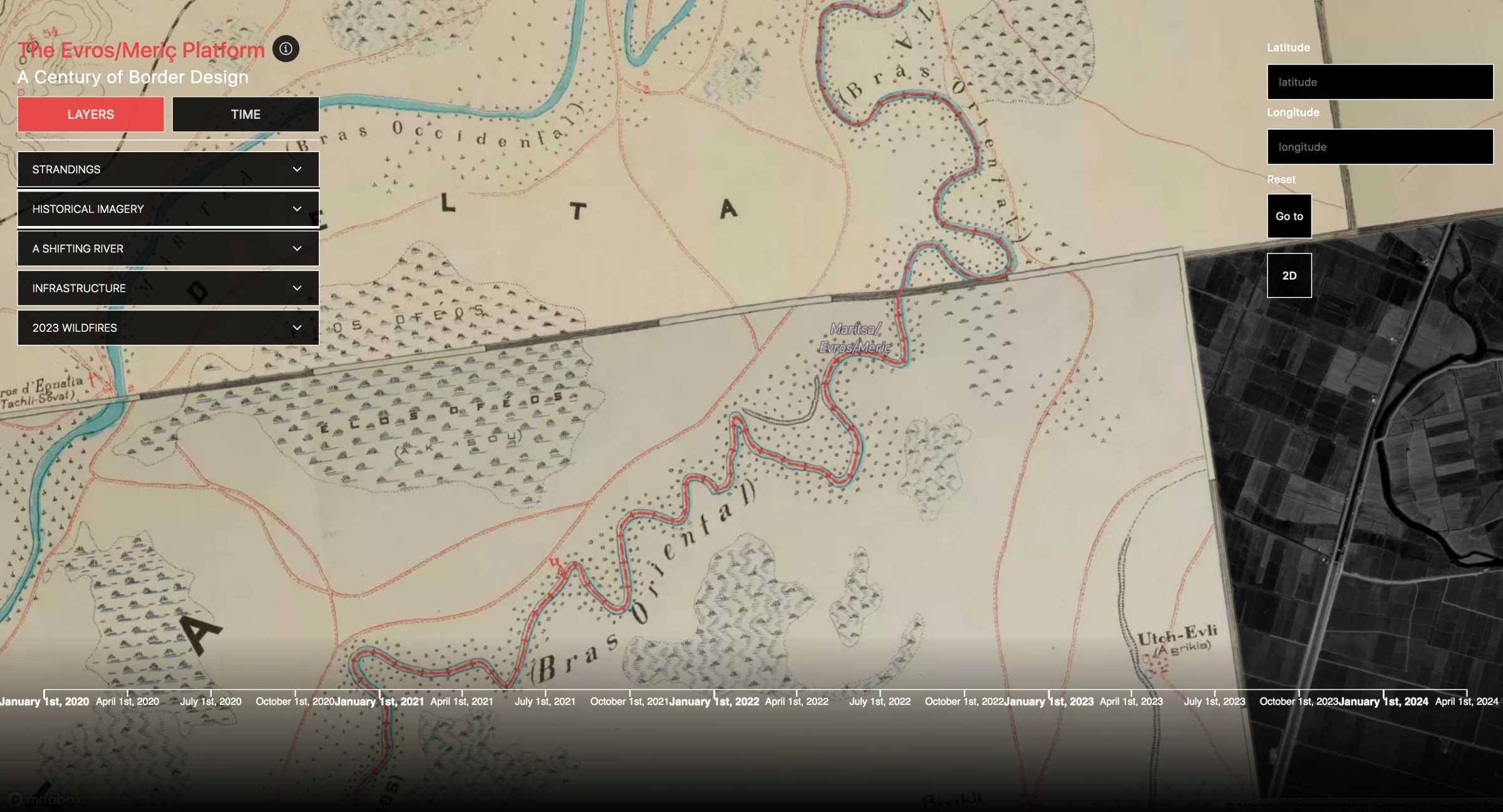

The border that separates Greece from Turkey along the Evros/Meriç river was first drawn a century ago. The 1923 Lausanne Peace Treaty defined it as the median line between the river banks, and a multilateral demarcation committee set out to plot its precise course. By January 1926, the committee had drawn the border line, and explained its process in a document that became known as the ‘Athens Protocol’. According to the committee, the border should not follow the changes of the river’s route, but instead be forever fixed to its 1926 course.

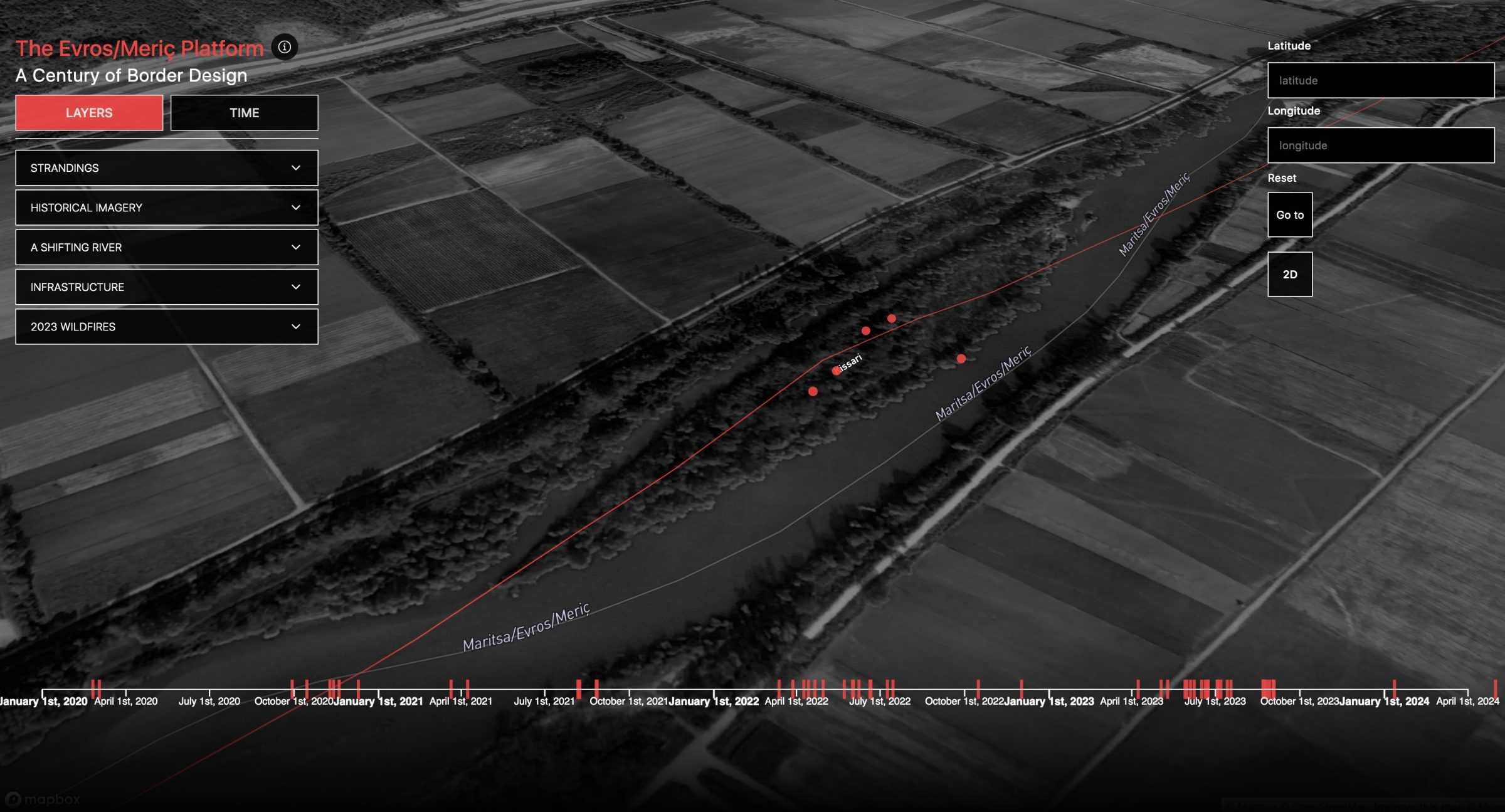

A century later, the river is a hotspot for illegal crossings of refugees and migrants into Europe, as well as a laboratory for border defence technologies at the continent’s frontier. Meanwhile, the course of the river has changed over the century. Islands have disappeared and formed, and riverbanks have shifted. Parcels of Turkish land now sit on the river’s western bank, and Greek land on the east: for people wishing to cross into Europe, there are two borders at the Evros/Meriç today. The space between the 1926 border line and the watery border formed by the river’s course today is a space of exception. In those 9404 hectares, both states weaponise territorial ambiguity to violate the rights of asylum seekers with impunity.

Within that space, migrants and refugees are hunted, detained, tortured, ‘pushed back’ across the river by border guards, or abandoned on islets for days, even weeks. A military buffer zone, dotted with guard stations, watchtowers and fences, runs along both banks of the river, excluding monitors, researchers, and medical professionals. Survivors of ‘pushbacks’ describe having their phones, documents, and possessions confiscated and often thrown into the river, ensuring that little documentation of this lethal border zone escapes to the outside world.

The platform works across these two distinct but overlapping time-scales to map the gradual construction of the Evros/Meriç as a zone of border death.

Mapping the Evros/Meriç Border Apparatus

The Border Line

Tethered to a ghost river, and only available to the two countries’ military cartographic services, to this day the precise course of the border line remained unknown to civil society actors and border crossers alike, as well as to international fora which are often called upon to mediate in the rescue of stranded migrant groups. Both states take advantage of this ambiguity, intentionally abandoning asylum seekers in indeterminate spaces in the river, and later denying responsibility for their rescue. Drawing from the original demarcation maps and from publicly available material from the Hellenic Army Cartographic service, this platform plots for the first time the precise course of the border line. The platform also allows users to import coordinates and examine them against the accurate border line. In this way, the map aims to offer a valuable tool for organisations and researchers who receive distress signals from stranded groups, and to exert pressure for their timely rescue.

A Shifting Border, 1923-2024

The river’s gradual shifting away from the original demarcation line has long been the subject of contestation and territorial dispute between the two littoral states. In recent years, however, Greece and Turkey have made strategic use of this territorial ambiguity in order to deter and kill asylum seekers, and to obfuscate traces of this violence. The platform traces this century-long transformation of the river landscape and tracks the river’s shifting course across space and time to interrogate the lethal implications this flexible territorial condition has on border crossings today.

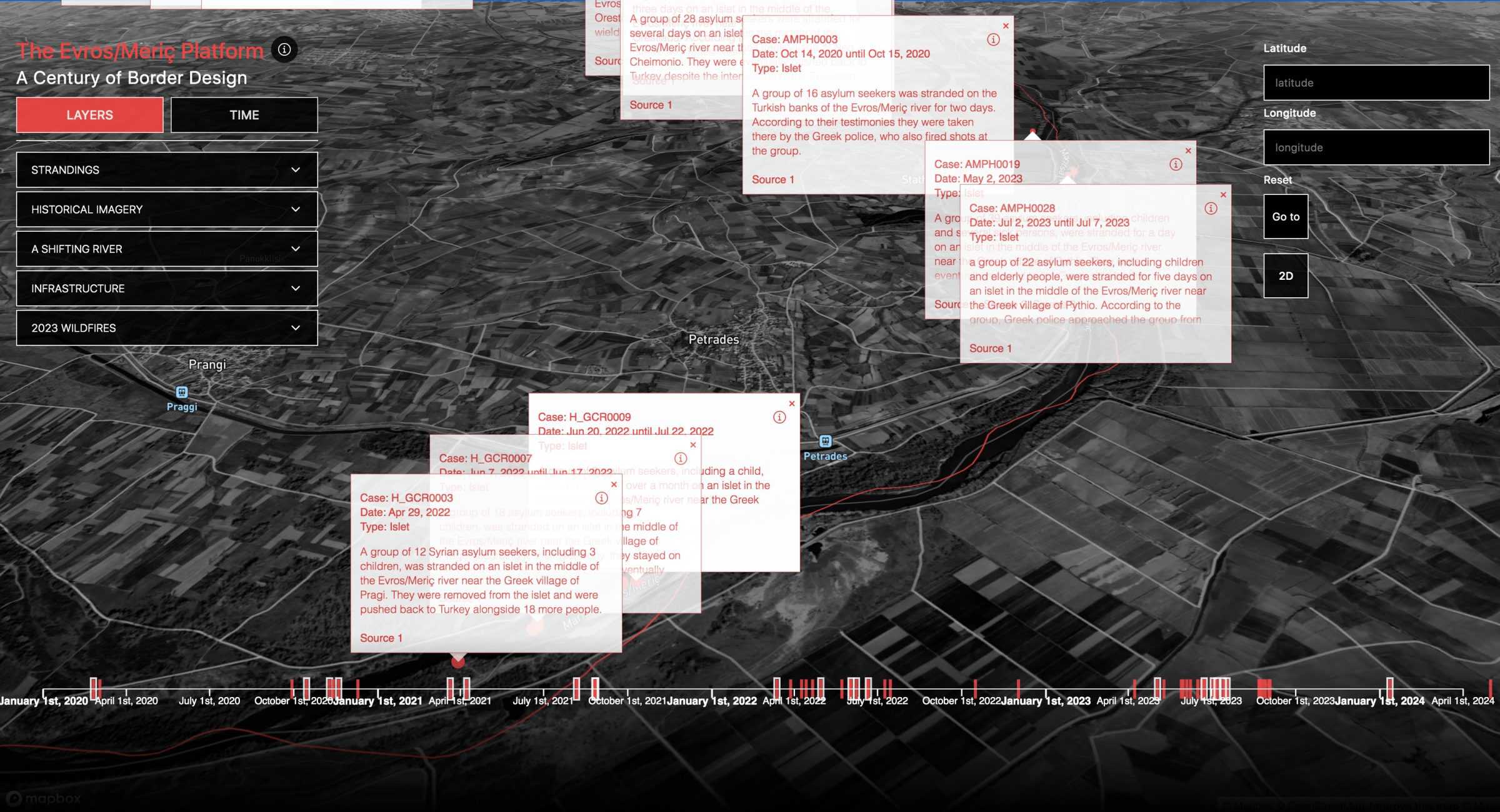

Strandings, 2020-2024

Since early 2020, more than sixty groups of asylum seekers that attempted to cross into Greece found themselves stranded on islets in the middle of the river. These groups were either led there by smugglers or border guards from the Turkish side of the river, or forced there by Greek authorities during pushbacks. In both cases, the islets are used as spaces where asylum seekers are abandoned for weeks on end, often without clothes, food or water, so that either littoral authority can deny responsibility for their reception and rescue. Fatalities from lack of access to food, water and medical care, insect and snake bites, hypothermia, drowning, or injuries are a common outcome of this practice.

The project collects, archives, and analyses evidence on all known cases of strandings on islets and other interstitial spaces along the river border, demonstrating patterns of a widespread and systematic practice of abandonment which intentionally exposes asylum seekers to the elements as a strategy of border deterrence.

Riparian Infrastructures

Despite it often being described as a ‘natural’ border, a century of geoengineering and border fortification has transformed the Evros/Meriç into a hybrid landscape of border defence.

The 20th century saw the transformation of the riparian landscape through a series of embankments, levees, moats and canals meant to regulate the flow of water in the region while also stabilising the river banks to the 1926 condition. Ghosting this hydraulic infrastructure today is an ever-expanding architecture of border guard stations, surveillance towers, anti-vehicle minefields, dirt roads used exclusively for border patrol, and the border fence.

The fence was first built along 11.5 km of the border in 2011, and expanded to seal off another 32 km after the events of March 2020. While the 2011 fence was erected along the only stretch of the border that runs over land, the second and third stages of the fence in 2020 and 2023-24 were built chiefly along parts of the old riverbed which now run dry, and was designed to double as an anti-flood embankment. In the few places where the fence is built along the current river banks, it creates a two-metre wide strip excised from Greek territory where asylum seekers who manage to cross the river – but not the fence – are abandoned in a similar fashion as on islets. Fence and river are now entangled and co-constitutive as vital parts of the complex assemblage that is the Evros border environment.

Today, the Evros/Meriç is not a natural obstacle but a hyper-designed infrastructural object. The platform offers a counter-cartography of this hybrid riparian infrastructure across its various operative scales.

The 2023 Fire

On 19 August 2023, a wildfire broke out near the river Delta. The fire burned for 17 days, covering an area of nearly 1.000.000 square kilometres, making it the largest and longest-lasting wildfire ever recorded in Europe. The fire brought about an environmental catastrophe, reducing the forest of Dadia, one of the continent’s most important habitats for birds of prey and a protected wildlife reserve, to ashes. Dadia was also frequently crossed by asylum seekers who took to forests of the nearby Rhodope mountains in order to avoid being intercepted by border patrols.

Though it became known from early on that the fire started from lightning, the media and top government officials in Greece were quick to blame migrants for it, declaring the region under attack. Local far-right vigilantes launched a ‘pogrom’, abducting and detaining migrants and posting their actions on social media.

When the flames were put out, the charred remains of 20 asylum seekers were found in the forest. Travelling in different groups (a group of 18, and two people travelling alone), the victims had found themselves stranded in different locations in the forest and were unable to escape the blaze.

Doubling down on its hostile rhetoric towards migration, the Greek government blamed these deaths on ‘smugglers and NGOs’. Instead, research shows that migrants chose to follow this longer and dangerous route through the Rhodope mountains due to the threat of pushbacks for groups intercepted near the river.

The platform maps the expansion of the fire over this 17-day period along with the locations of groups of asylum seekers that were killed or endangered by it to highlight both the scale of the environmental catastrophe and the deadly effects of the intentional directing and stranding of border crossers to the hostile environments of Evros – whether by water or fire.

What is the purpose of this platform?

The platform is meant as a useful counter-cartographic tool at the hands of asylum seekers, activists, humanitarian workers and researchers in their pursuit of accountability for ongoing border crimes, and in their efforts to support stranded groups in the region. It is also meant as a detailed repository of geo-referenced archival information that can speak to the gradual transformation of the Evros/Meriç river into a border weapon. The platform, therefore, provides a space where the two overlapping scales of border violence, the fast and the slow, can be examined in relation to each other.

Mapping border lines is usually a gesture of power. Instead, rather than enforcing this border, our contribution aims at destabilizing its lethal operation. By bringing much-needed clarity over this intentionally clouded territorial condition, and by demonstrating not only how dangerous, but also how unruly and unstable the river and its sediments are as a national boundary, this platform looks at the Evros/Meriç river through an abolitionist perspective.

Where does this platform get its data?

The information contained within the platform is the result of extensive collaborative research led by Forensis with the participation of Alarm Phone, Border Violence Monitoring Network, and the Greek Council for Refugees.

The cases of strandings mapped within are aggregated through the monitoring and legal efforts of the three above-mentioned organisations who receive images and location coordinates directly from asylum seekers crossing the river and alert authorities about stranded groups in an effort to secure assistance. Additional material was sourced from open source research.

The original demarcation maps and the 1926 ‘Athens Protocol’ were sourced and digitised at the United Kingdom’s National Archives. Historical aerial photographs and further GIS information was sourced from the Hellenic Army’s Cartographic Service and the Greek National Cadastre.

Information on infrastructures comes from analysis of open source material such as satellite imagery, photos and videos posted social media by asylum seekers, as well as operational documents, contracts and tenders uploaded by the Greek and European authorities in their respective transparency portals. Fieldwork was also conducted.