In Partnership With

Additional Funding

- Safe Passage Foundation (formerly known as Stiftungsfonds Zivile Seenotrettung)

- Allianz Foundation

- Open Society Foundations (OSF)

Collaborators

- Amnesty’s Crisis Evidence Lab and the Digital Verification Corps (DVC) at the University of California, University of Cambridge and University of Essex

- Bellingcat Global Authentication Project

- Border Violence Monitoring Network

- Aegean Boat Report

- Alarm Phone

- Refugee Support Aegean

- Legal Centre Lesvos

- Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)

- de:border | migration justice collective

- Refugee Biryani & Bananas

- Greek Council for Refugees

- Human Rights Legal Project

- HIAS Greece

- The Department of Computer Science at Brown University and students in ’CS for Social Change’, Spring 2022

Methodologies

Forums

Originally published on 15 July 2022, this page was updated on 19 January 2024 to reflect the addition of over 1,000 additional cases to the platform, bringing the total to over 2,000 separate incidents that resulted in the expulsion of 55,445 people, 24 deaths and 17 disappearances over three years (March 2020 – March 2023).

For more than a decade, migrants and refugees making the sea crossing from Turkey to Greece have suffered egregious and well-documented violence at the EU’s southeastern frontier, including forced detention, arbitrary arrest, beatings and non-assistance.

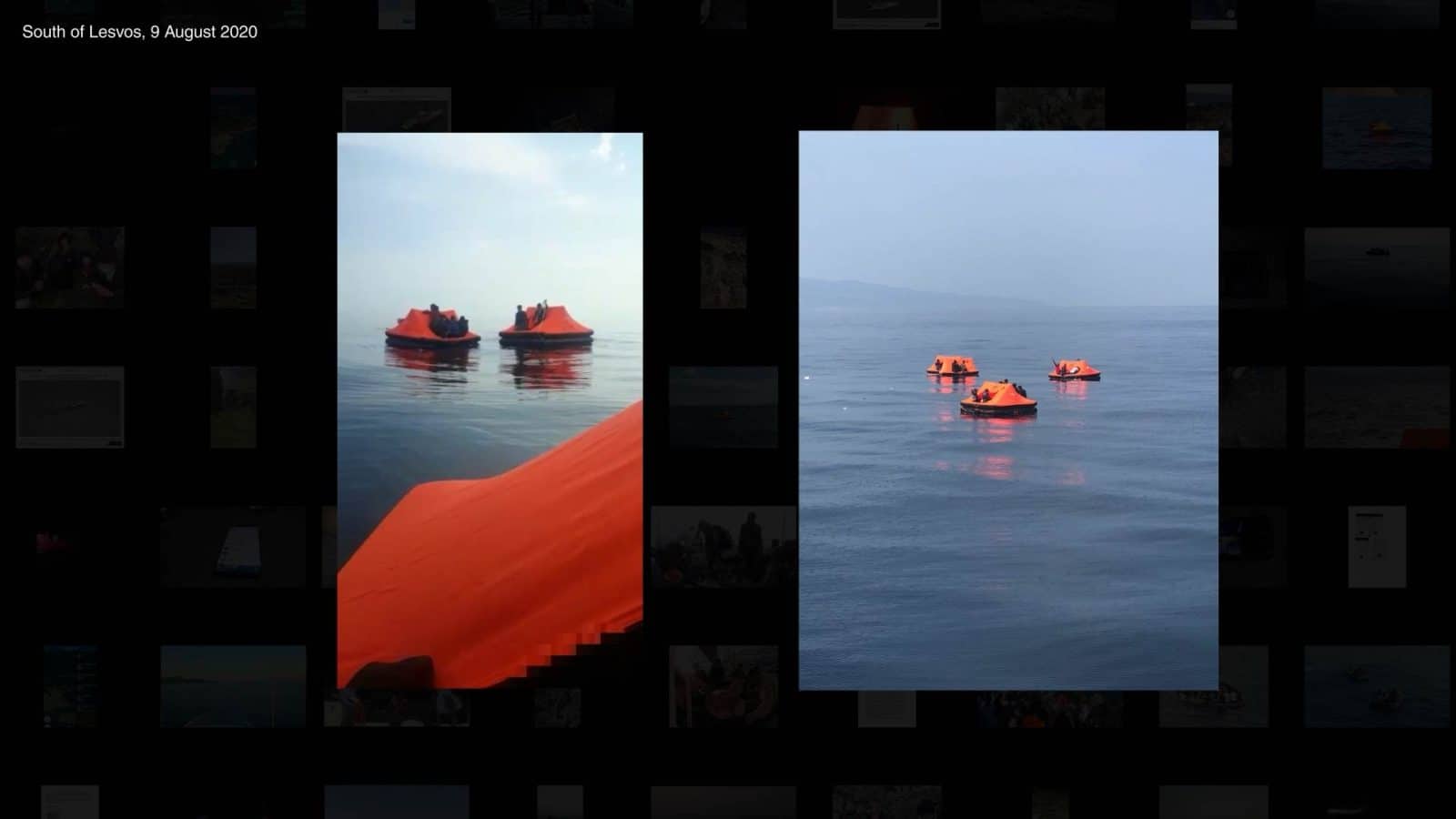

Since March 2020, a new method of violent and illegal deterrence has been practiced. Migrants and refugees crossing the Aegean Sea describe being intercepted within Greek territorial waters, or arrested after they arrive on Greek shores, beaten, stripped of their possessions, and then forcefully loaded onto life rafts with no engine and left to drift back to the Turkish coast.

‘Drift-backs’, as the practice of abandoning asylum seekers at sea has come to be called by some, have become routine occurrences throughout the Aegean, often resulting in injuries and drownings. Today, the scale and severity of the practice continues to increase, with ‘drift-backs’ reported from the coast of the Greek mainland, and as far south as Crete.

Archipelago of obscurity

‘Drift-backs’ are manifestly illegal and contravene international protocols, including the inalienable rights to apply for asylum and to seek rescue at sea.

Despite mounting pressure, to this day the Greek authorities deny that ‘drift-backs’ take place in the Aegean. The Aegean Sea is not only a hotspot of state violence but also a testbed for ways to obfuscate it. Entire maritime zones, militarised islets and uninhabited rocks remain off-limits to civilian access and oversight, and are exclusively navigated and managed by the military and Coast Guard. Rescuers, activists and journalists who operate in the region and report on human rights violations have been repeatedly criminalised and intimidated by authorities. Migrants who are intercepted there have their phones taken and destroyed before they themselves are made to disappear.

Implausible denials

Mobilising the direction of sea currents, the Hellenic Coast Guard uses ‘drift-backs’ to expel asylum seekers without having to enter Turkish territorial waters. Instead, natural processes and geographical features of the Aegean archipelago—currents, waves, winds and uninhabited rocks—carry out the expulsion, distancing the perpetrators from the impact of their lethal actions. These natural processes provide a measure of deniability for those perpetrators, shielding them from accountability.

But as our research shows, this is not a plausible deniability—rather, what emerges is a systematic, calculated practice, in which actors are aware of the lethal consequences of their actions.

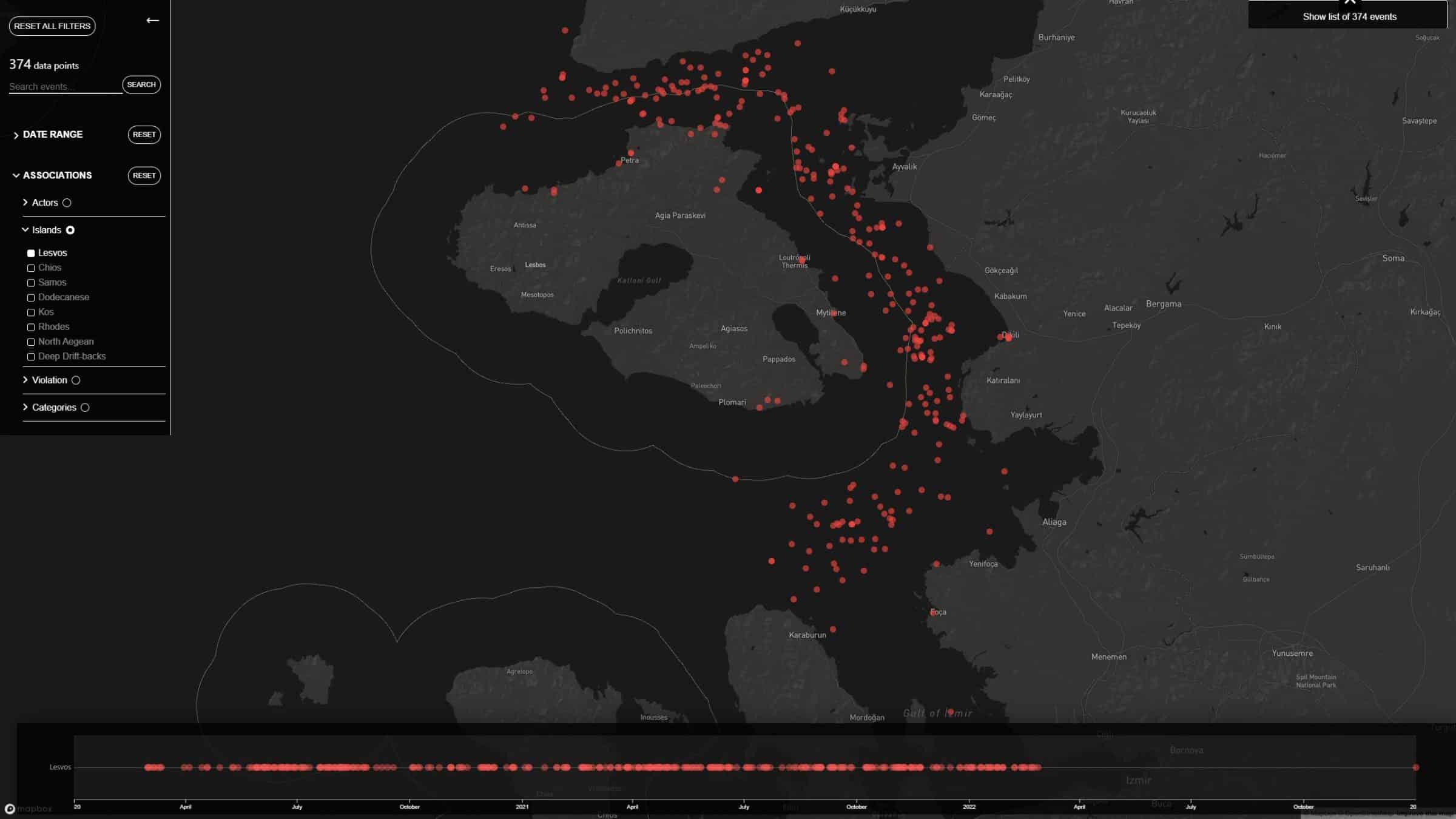

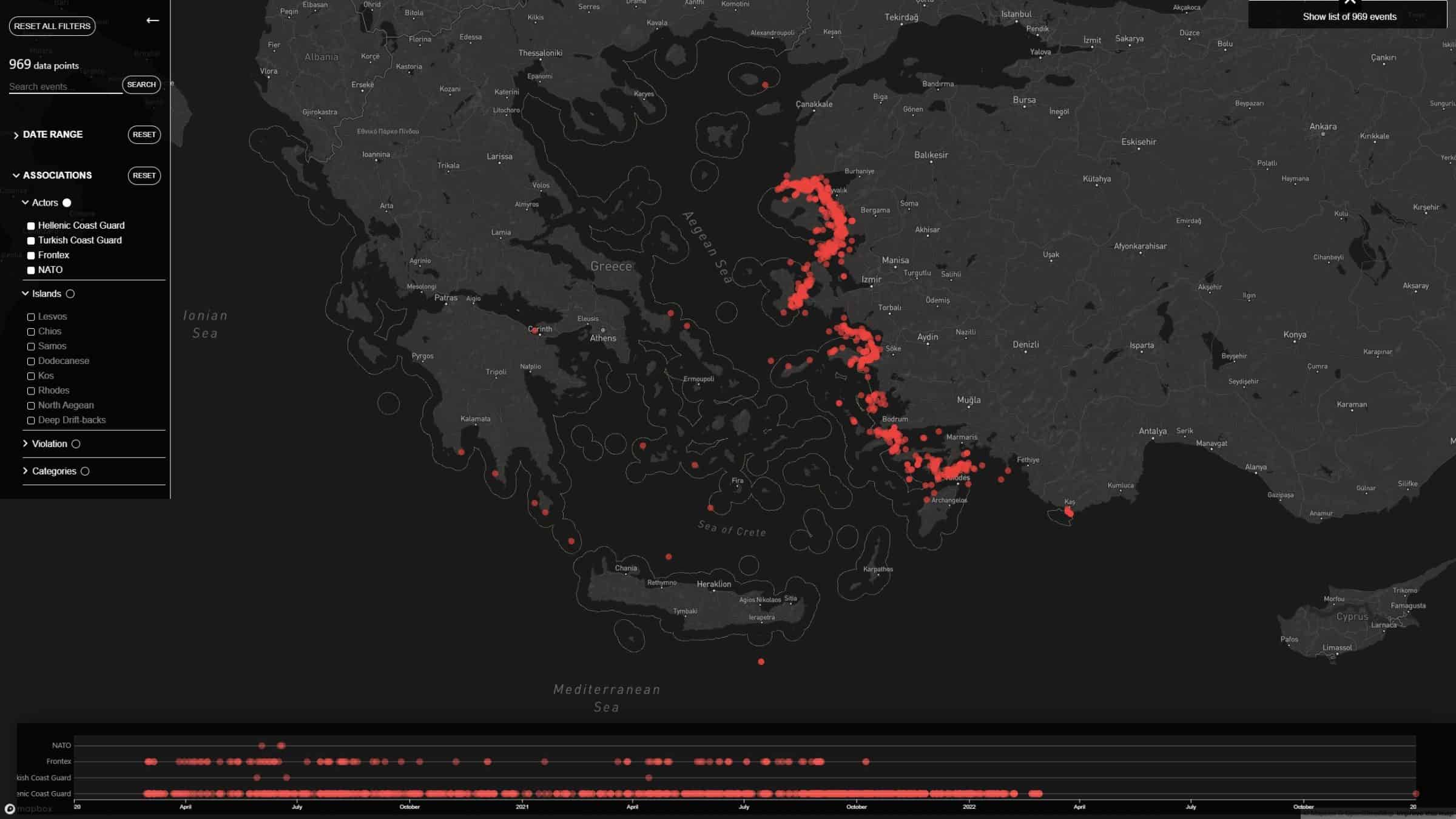

Mapping drift-backs

Spanning a period of three years, from 28 February 2020, when the first drift-back case was reported and documented, to 28 February 2023, this interactive cartographic platform hosts evidence of 2,010 drift-backs in the Aegean Sea, this interactive cartographic platform hosts evidence of 2010 drift-backs in the Aegean Sea, involving 55,445 people Of these 2010 incidents, 700 were found to have taken place from, or off the shores of, Lesvos island, 238 off Chios island, 424 off Samos island, 283 off Kos, 212 off Rhodes and 123 in the rest of the Dodecanese. 26 deep ‘drift-backs’ were recorded, meaning that asylum seekers were intercepted deep inside Greek waters before being taken to the border and left adrift. One case was recorded in the North Aegean, off the island of Samothraki. FRONTEX, the European border and coast guard agency was found to have been directly involved in 122 of these cases, while it has knowledge of 417, having logged them in their own operational archives codified and masked as ‘preventions of entry’. In 3 cases, the German NATO warship FGS Berlin was present on the scene.

32 cases were recorded where people were thrown directly into the sea by the Hellenic Coast Guard, without the use of any flotation device. In 3 of these cases, the people were found handcuffed. 24 people were documented to have died during a drift-back, and at least 17 more went missing.

In mapping these cases, the platform is meant as a non-exhaustive and evolving tool, which will be updated at regular intervals for as long as this practice continues.

Where does this platform get its data?

The information contained within the platform is the result of extensive collaborative research led by Forensic Architecture and its berlin-based sister organization, Forensis, with the participation of Border Violence Monitoring Network, Bellingcat Global Authentication Project, Amnesty’s Crisis Evidence Lab and the Digital Verification Corps (DVC), and monitors and NGOs such as Alarm Phone, Aegean Boat Report, Refugee Support Aegean, Legal Centre Lesvos, MSF Greece, de:border / migration justice collective, Refugee Biryani and Bananas, Greek Council for Refugees, Human Rights Legal Project and HIAS Greece.

The material comes from four main sources: the monitoring efforts of AlarmPhone Aegean and Aegean Boat Report who receive images and location pins directly from asylum seekers crossing the Aegean Sea; FRONTEX’s own JORA (Joint Operations Reporting Application) database, obtained in the form of a redacted spreadsheet by Lighthouse Reports through a FOI request, and which covers the period of March 2020 – August 2021; and the website of the Turkish Coast Guard, who document the drifting vessels their crews come upon daily, and upload the visual material along with brief reports to their website. Additional material was sourced and shared by local monitors, media and activists, and from open source research, including from previously published investigations by Bellingcat, Lighthouse Reports, Der Spiegel, BBC, Al Jazeera and the New York Times.

We also conducted interviews with survivors and relatives of people who drowned in the Aegean or were pushed back, obtaining material directly from their phones, and visited locations where groups went missing to find and document the physical traces of their landings.

Terminology

Cases are categorised as verified, documented, and trajectory according to the evidence available. A case is logged as verified when it is either geolocated with a high degree of confidence in a way that confirms the location, time, and description given by the original source, or when the visual material or the cross-referencing of different sources allows us to confirm a drift-back has taken place without needing to geolocate it. Cases are logged as documented when we are unable to corroborate the report, but there is enough material to suggest a drift-back has taken place. Trajectory refers to cases for which we have more than one location, allowing us to map the movement of a group in space and time.

Locations are described as precise or approximate. Precise refers to locations we were able to geolocate with absolute precision, or, in the case of images and videos taken from the sea, within a margin of error of 100-200 metres. Approximate refers to locations that we were unable to verify, in which case we defer to the approximate location given by the source.

Evidencing the systematic and widespread nature of the practice and demonstrating relations between incidents, localities, and actors, this platform is already supporting ongoing legal action in local and European courts, independent monitoring, reporting, and advocacy, as well as growing demands for accountability and international calls for the defunding of national border guards and FRONTEX.

Update

29.08.2022

29.08.2022

During the week of the platform’s launch, leader of Mera25/DieM25 political party Yanis Varoufakis presented the platform’s findings in the Greek parliament, demanding that the government account for its role in the seemingly systemic violation of rights that the platform revealed.

Soon after, members of the European Parliament, sitting for the Green Party, sent the platform’s findings to the executive director of Frontex, the EU’s border control agency and coast guard, who in response on 3 August committed in writing to investigate every case contained within the platform which involved the agency – numbering more than 100. Analysis of web traffic to the platform suggests that, indeed, Frontex staff are regularly referring to its findings.

Update

19.10.2022

19.10.2022

On 12 October 2022, project coordinator and lead researcher, Stefanos Levidis, presented findings from the investigation at a meeting of members of the Bundestag, on the invitation of Green MP Julian Pahlke. And on 19 October, following growing discontent at Frontex’s operations, to which the revelations in the ‘Drift-backs’ platform have contributed, the European Parliament voted against releasing Frontex’s 2022 budget, placing significant pressure on the agency.

The platform is currently being used to support multiple ongoing or imminent legal cases filed at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), where Forensis and its partners will separately submit their own reports based on the results of the platform, and their related investigative work concerning rights violations in the context of migration.

Methodology

Methodology

To verify these thousands of pieces of evidence coming from different and sometimes contested sources, we followed a diverse methodological approach. Where groups of asylum seekers had shared their location while crossing, we logged these GPS coordinates on a map. We also extracted the coordinates and times visible on the radar of Turkish Coast Guard vessels, and when these were not readily visible on the radar screen, we looked for recognisable cartographic features, like island outlines, or the shape of the border line. When commercial or military vessels were visible in the background of photographs and videos, we obtained and mapped AIS data to further corroborate the location and time an incident took place. Roads, buildings and road signs visible in photographs and videos taken by people who had arrived on the Greek islands before being abducted and returned to Turkey, were also geolocated.

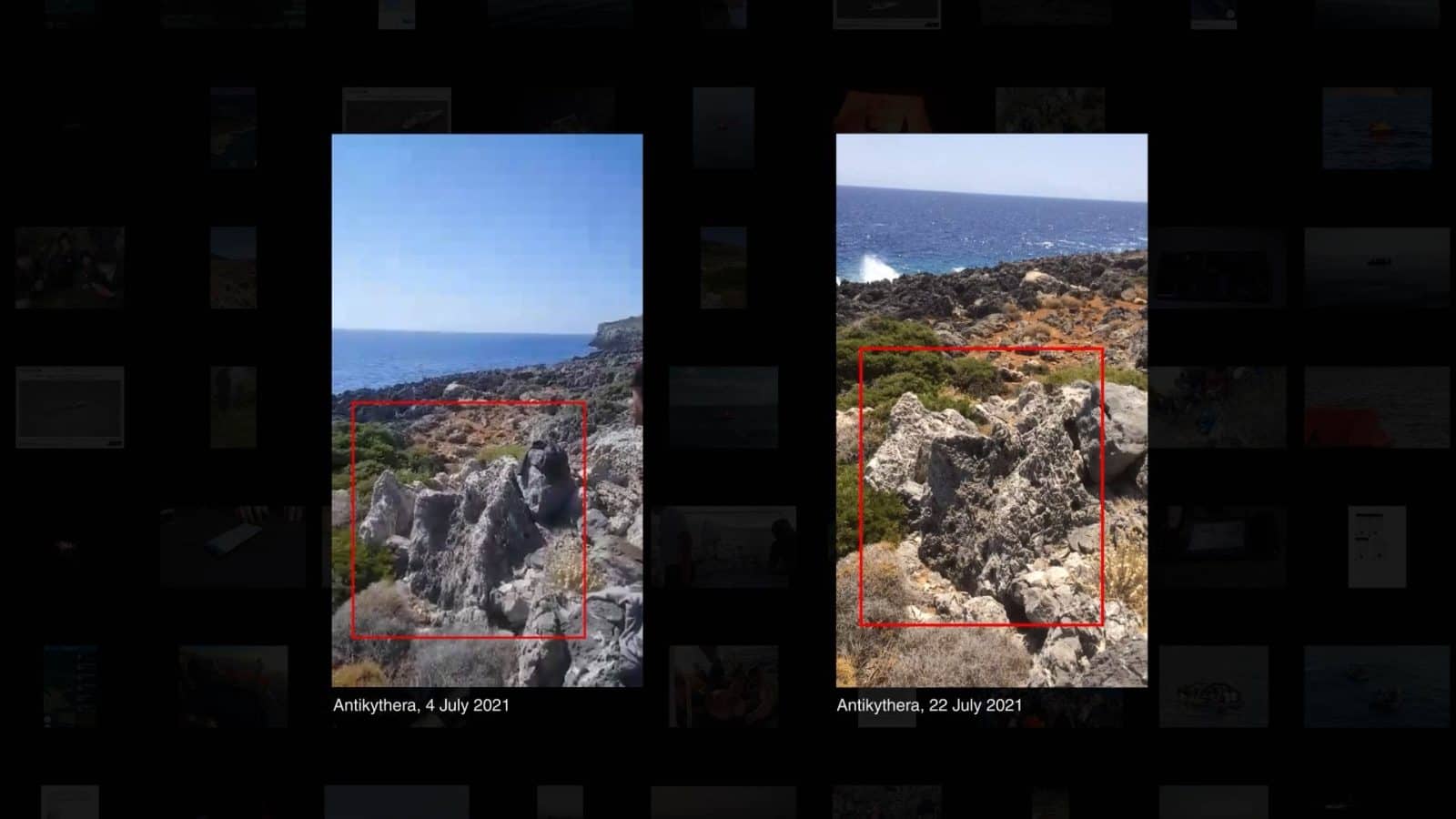

Such precise spatio-temporal information was rarely available. For most cases, we geolocated evidence by looking for identifiable features in the ridge lines and terrain of the Greek islands and the Turkish shores pictured in the imagery obtained.

We also used meteorological data to compare the weather conditions seen in photographs and videos with the date and time these were reportedly taken, and to determine possible drift trajectories.

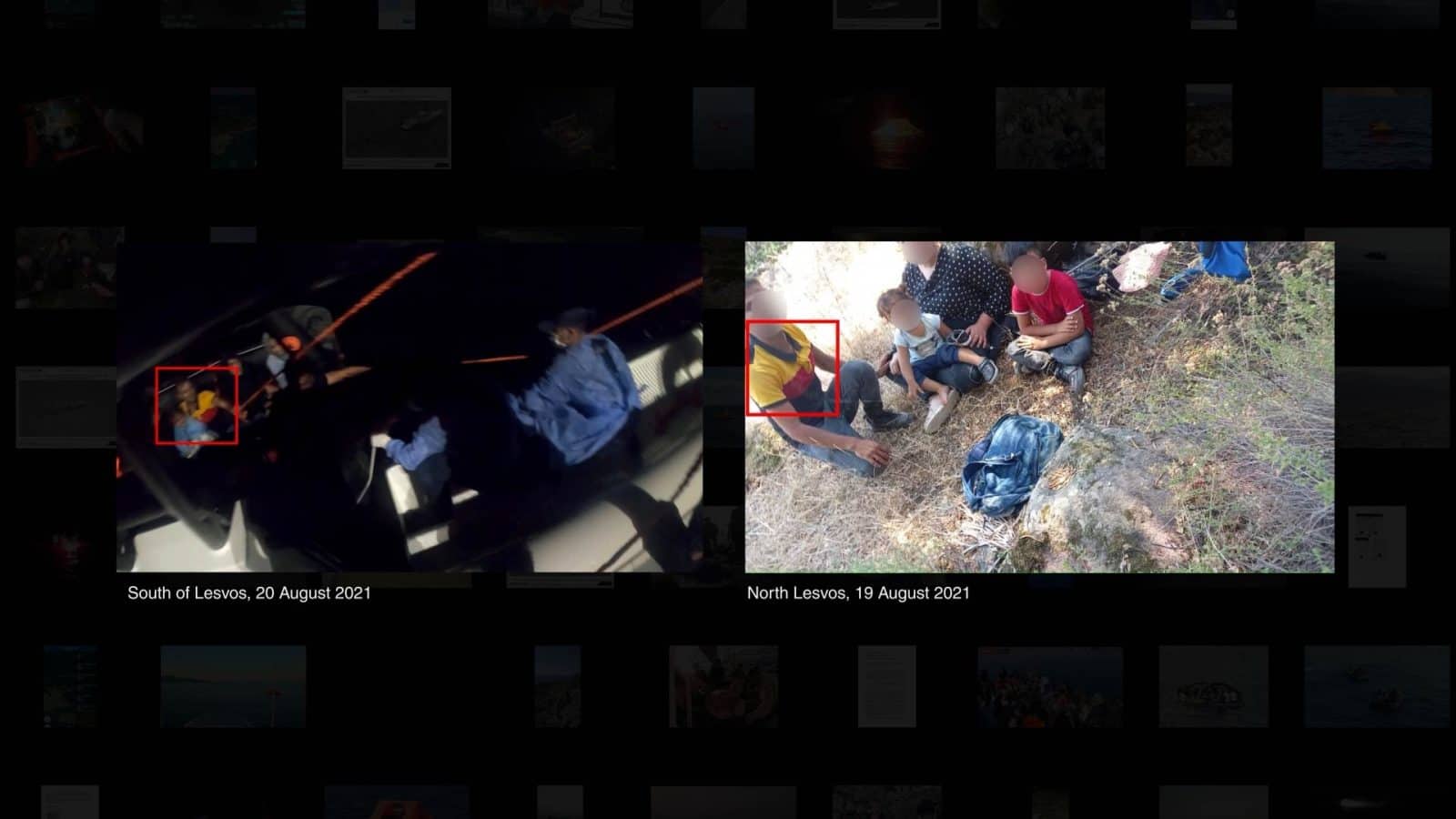

To establish a match between groups of people who had documented their landing on a Greek shore before vanishing and reappearing on a raft in Turkish territorial waters, we compared their body and facial features, and their clothes and garments.

To match material from different sources and points of view capturing the same event, we modelled and compared the vessels and life rafts pictured.