Date of Incident

Location

Publication Date

Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Forums

Exhibitions

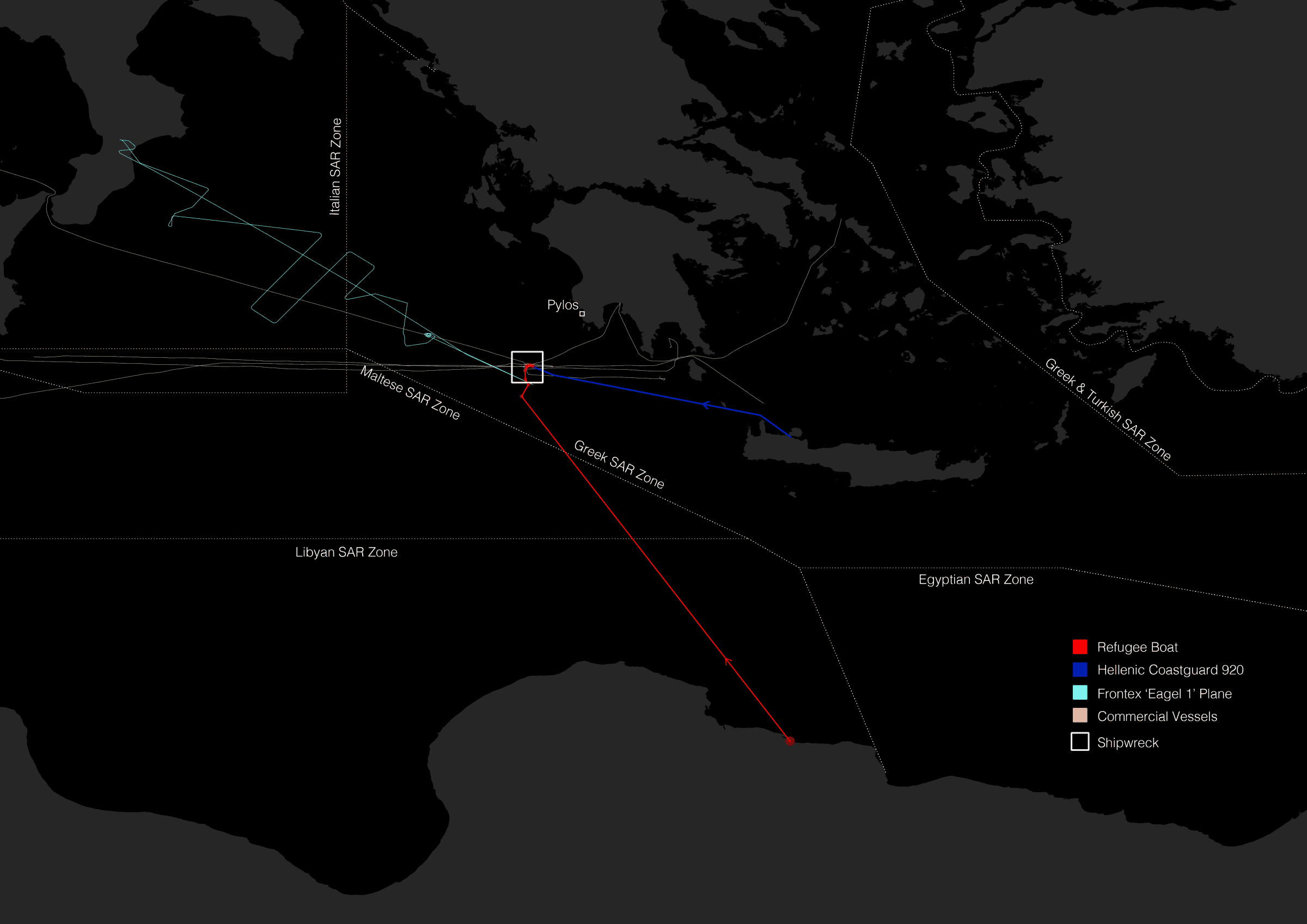

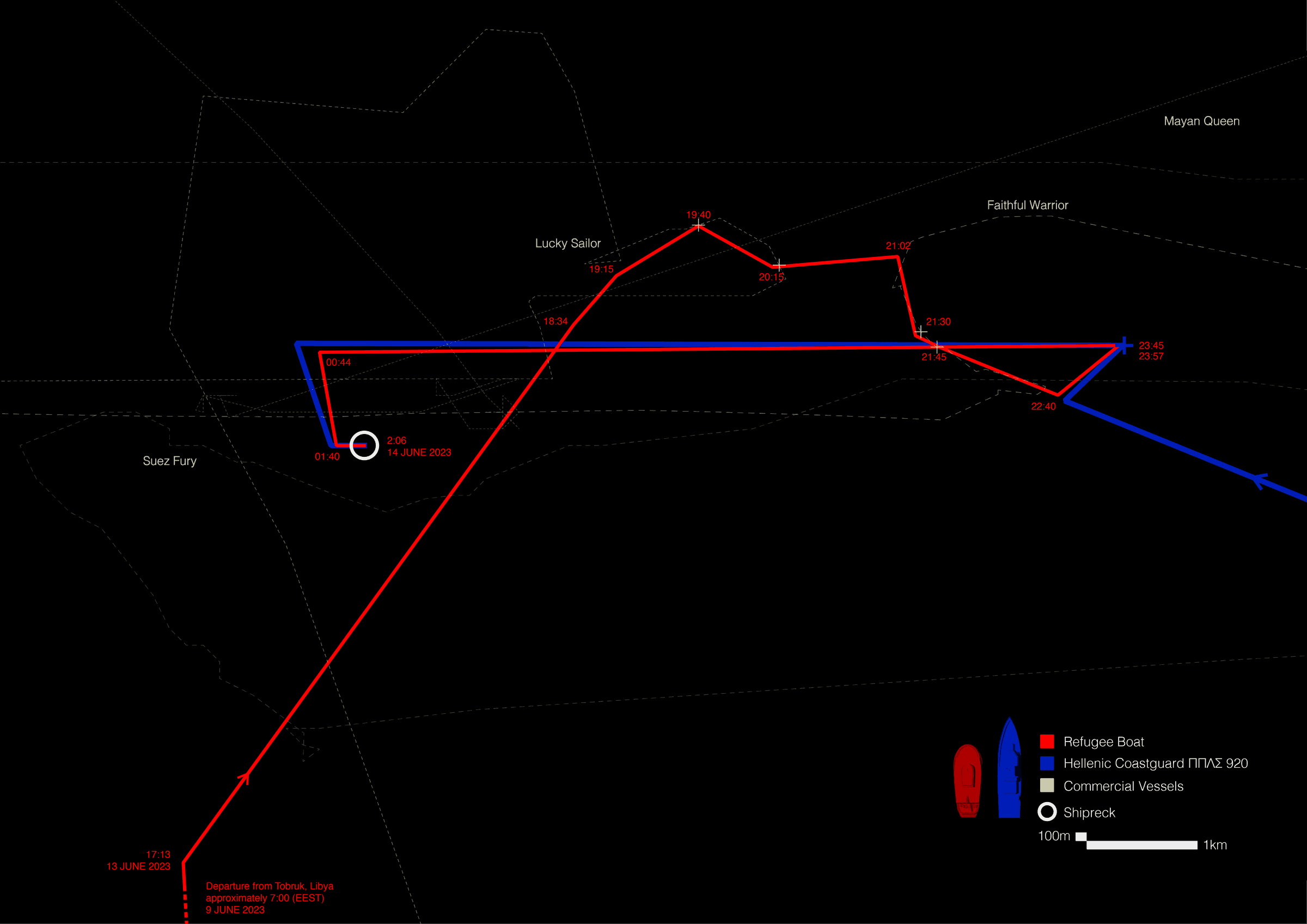

On 14 June 2023, the Adriana, a boat leaving Libya for Italy with hundreds of migrants on board, sank inside the Greek Search and Rescue (SAR) zone in the Mediterranean Sea. This would become the deadliest migrant shipwreck in recent history. Our digital reconstruction of the boat’s trajectory reveals inconsistencies in the Hellenic Coast Guard’s (HCG) account and indicates that over 600 people drowned as a result of actions taken by the HCG.

In the hours following the shipwreck, conflicting accounts about the incident began to circulate. The HCG denied responsibility, claiming that people onboard resisted offers for assistance, and that the boat capsized due to a sudden shift in weight. The survivors unanimously contest this account, blaming the HCG for multiple failed attempts to tow the boat, which ultimately destabilised it and led to its capsizing.

The incident took place at night and in international waters inside the Greek Search and Rescue (SAR) zone, meaning Greece was the coastal state responsible for initiating the necessary search and rescue operations. The wreck now rests 5,000 metres under sea level in the ‘Calypso Deep’, the deepest point in the Mediterranean, rendering its retrieval impossible. The only witnesses to the shipwreck are the 104 survivors of the migrant boat and the crew of a small open sea patrol vessel operated by the HCG, number ΠΠΛΣ 920, the same vessel accused by witnesses of the fatal towing.

According to our analysis and cross-referencing of data, there appear to have been a series of efforts by the HCG to distort and manipulate evidence related to the incident and silence witness accounts. Nearby commercial vessels that were initially summoned by the HCG to provide assistance were subsequently ordered to leave after the ΠΠΛΣ 920 arrived on the scene. Likewise, repeated offers by Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, to deploy aerial surveillance assets were ignored, and none of the several cameras onboard the ΠΠΛΣ 920 nor its AIS tracking system were activated that night as is required.

Furthermore, all the survivors of the wreck had their phones confiscated by members of the HCG. Some survivors we interviewed mentioned that these phones, protected in waterproof cases, included videos they took of the moments leading up to the capsizing of the boat. Yet none of these phones have been returned, despite repeated requests from their owners. The first testimonies from survivors gathered by the HCG the day after the incident display signs of possible manipulation: their accounts use identical, boilerplate language and all fail to mention the towing that migrants later reported to have experienced.

Questions surrounding the sinking and the Greek state’s reluctance to provide clear answers demand a detailed reconstruction of the incident and the events leading up to it

Methodology

Forensis researchers built an interactive cartographic platform that maps the itinerary of the migrant boat from its point of departure on the eastern Libyan coast to the location where it sank inside the Greek Search and Rescue (SAR) zone in international waters. Our map brings together different information sources, including distress signals shared by the vessel’s passengers; videos and photographs of the trawler taken by the HCG, Frontex, and nearby commercial vessels; vessel tracking and flight path data; satellite imagery; as well as the logs and testimonies handed to the Greek authorities by the captain of the HCG vessel ΠΠΛΣ 920, which was present on the scene. This data is cross-referenced with the testimonies of 26 survivors who were interviewed by the our team of researchers and a coalition of journalists from the Guardian, STRG_F (ARD/Funk) and Solomon investigating the case.

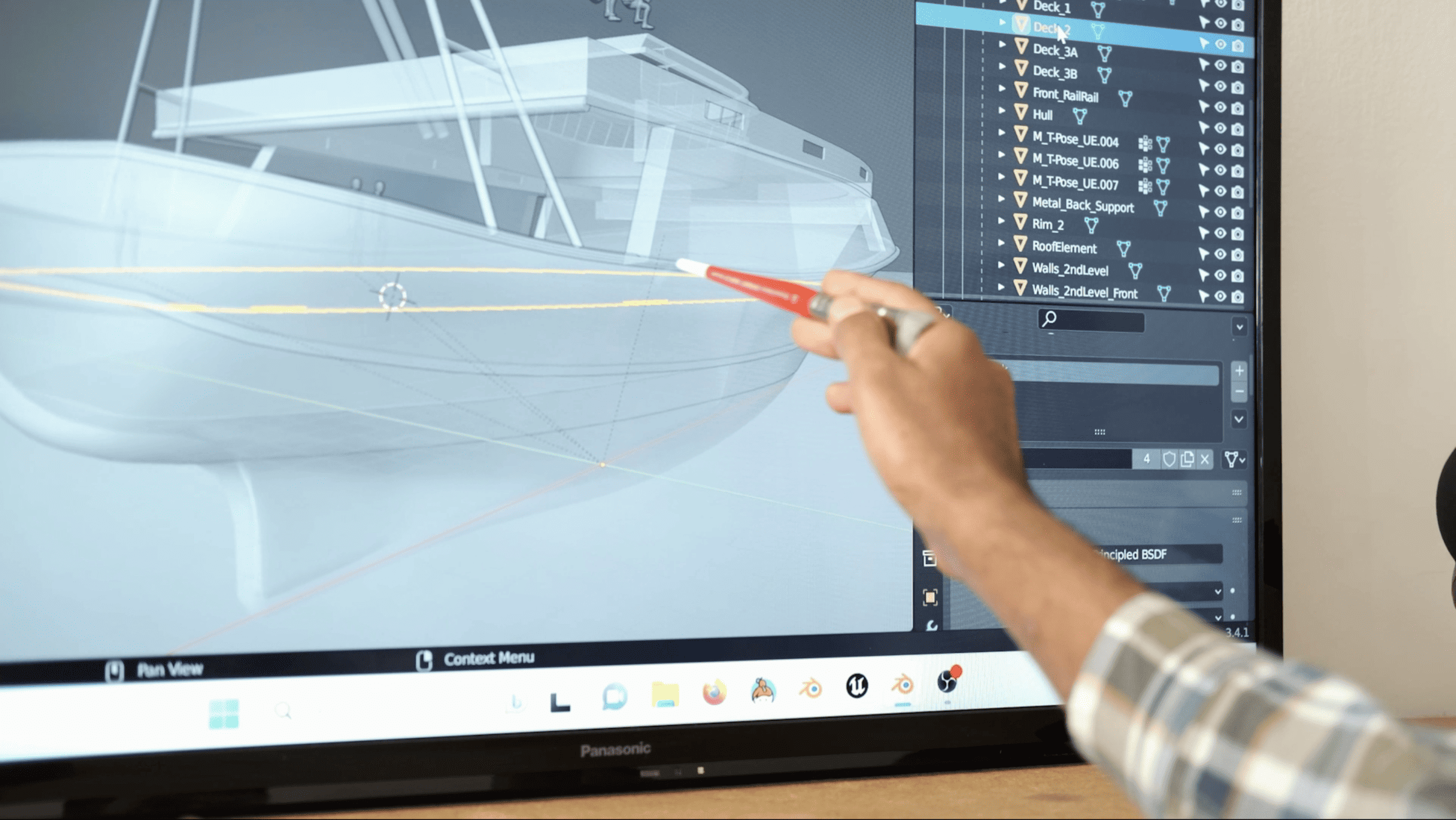

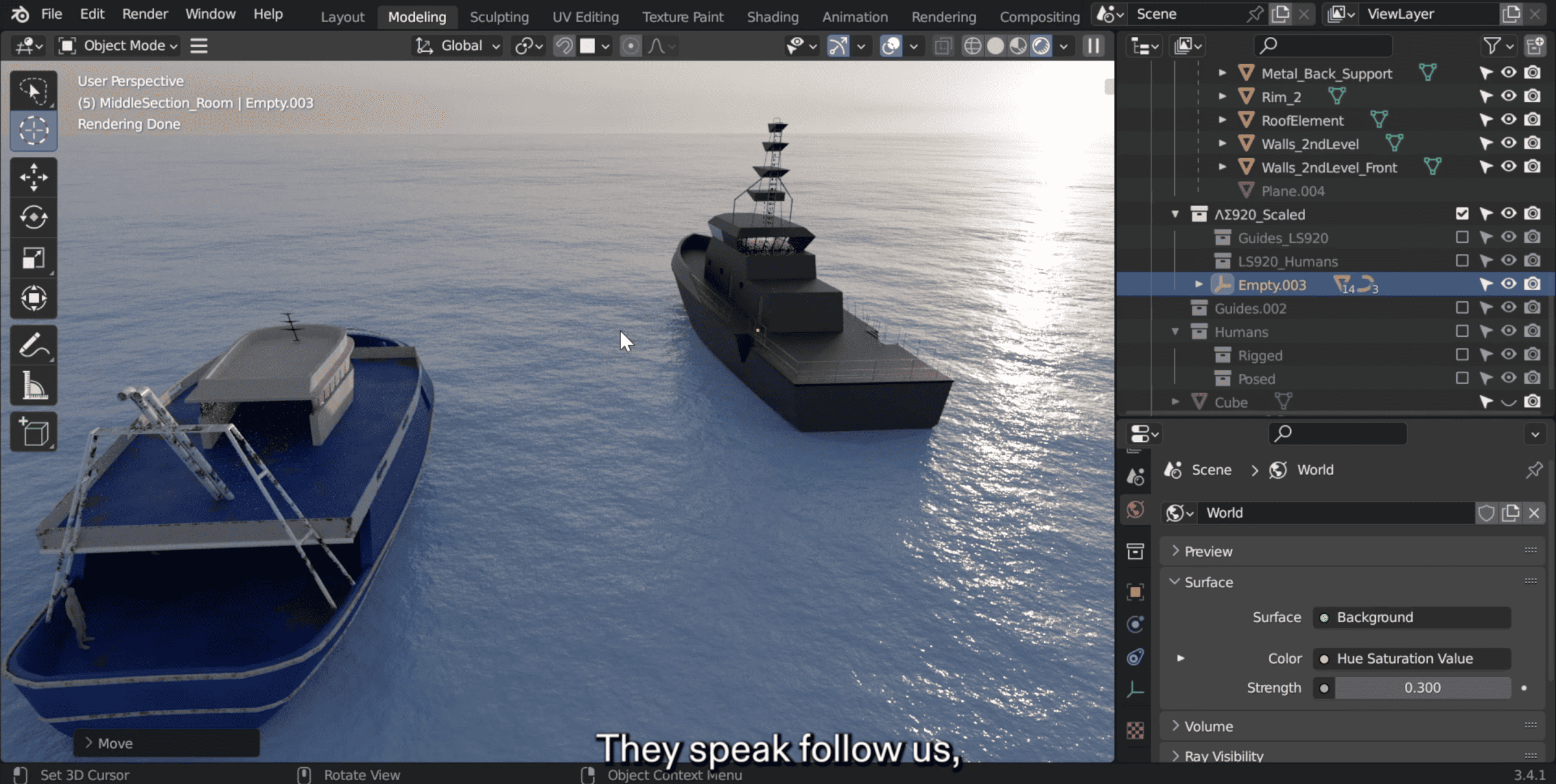

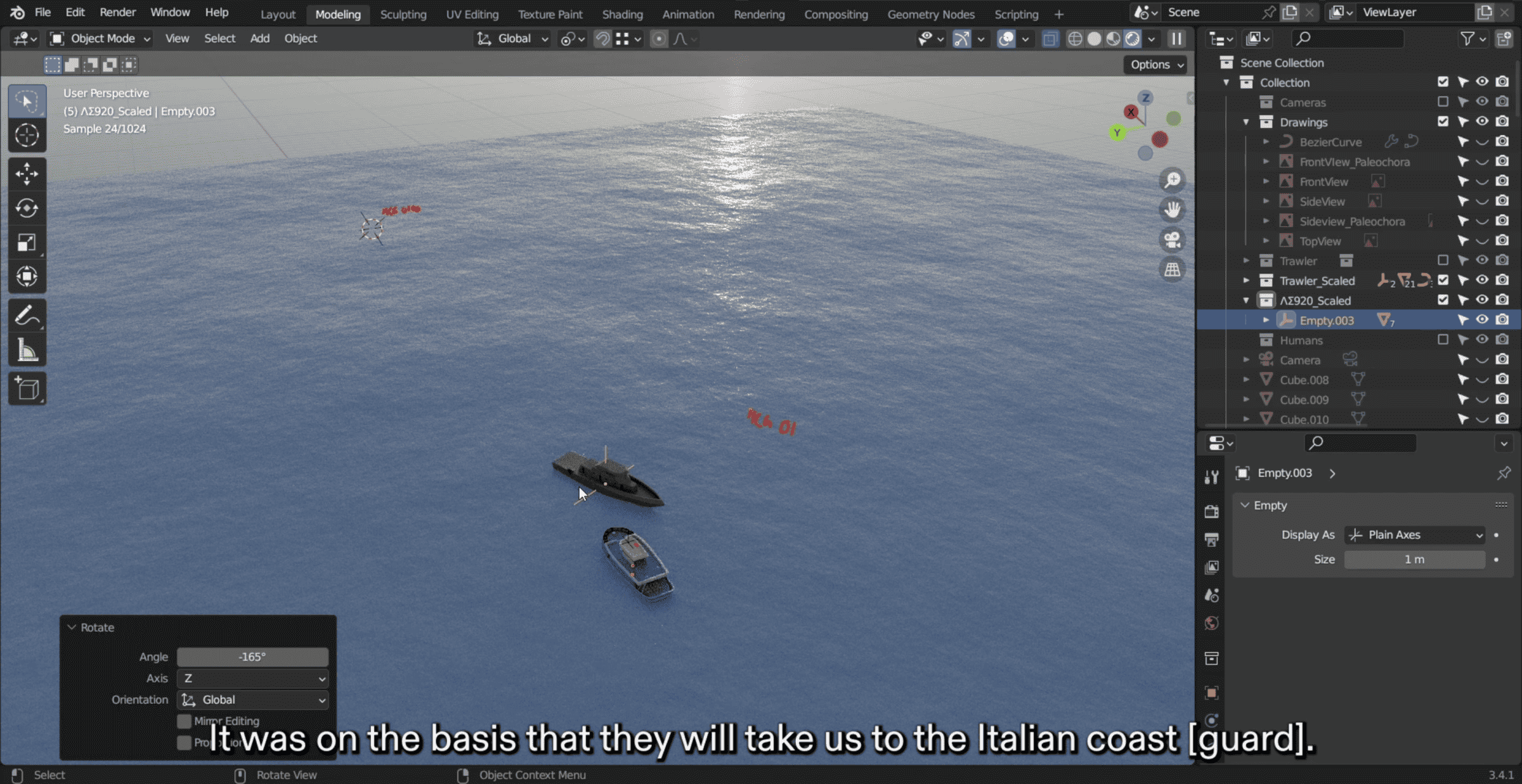

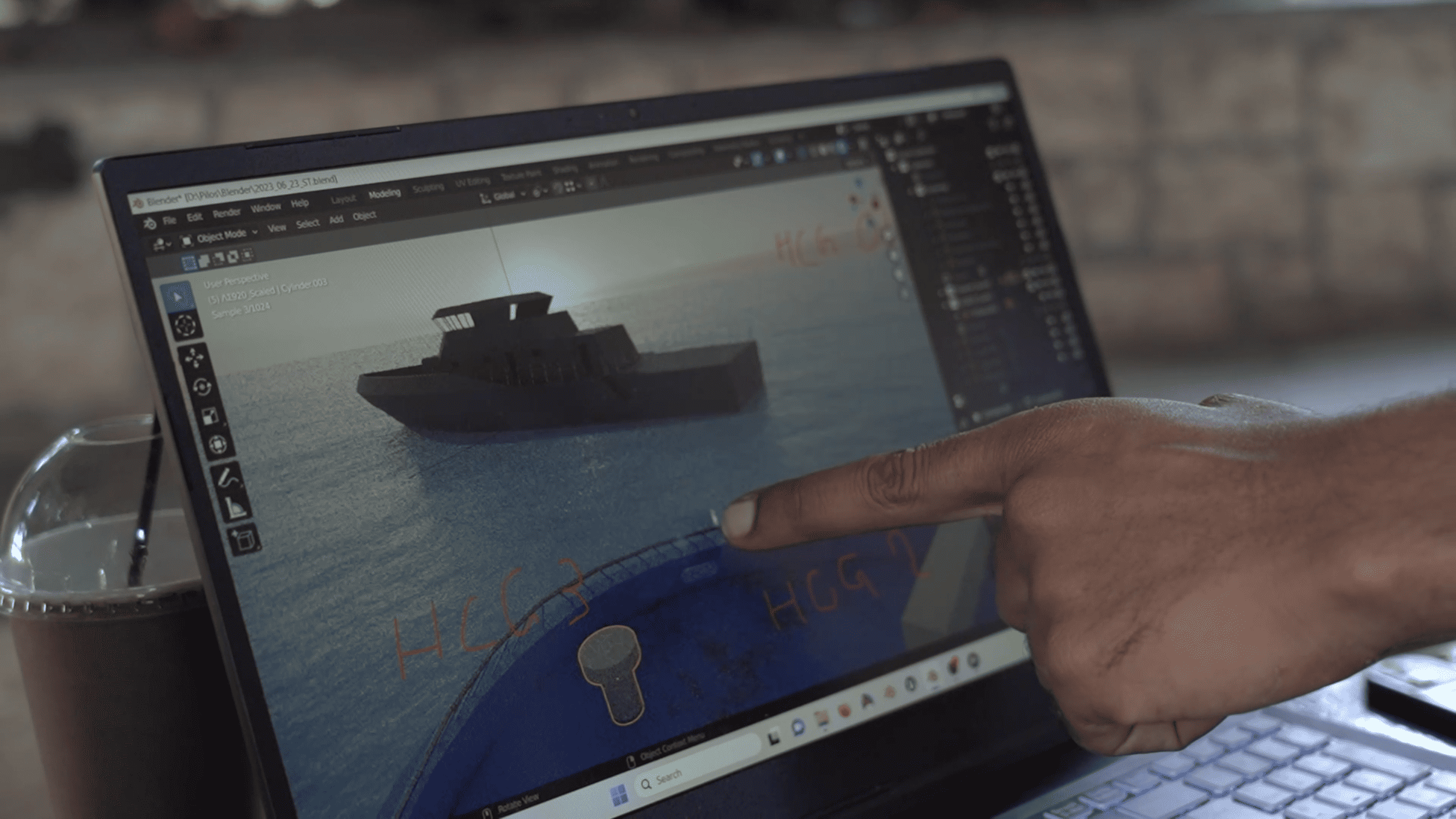

We used the same photographs and videos to produce 3D models of the sunken migrant boat and HCG vessel ΠΠΛΣ 920, which we shared with the lawyers representing the survivors to use in their gathering of testimony. We then used these models to conduct ‘situated testimony’ interviews with five survivors, two men from Syria who were sitting on the top, outer deck at the time of capsizing, and three men from Pakistan who were sitting inside, on the middle deck. With the help of these models, the survivors reconstructed the conditions on the boat, and events that led to the sinking from their respective perspectives.

The migrant boat, had three decks—lower, middle and upper—all filled with people. Drawing on accounts from survivors we estimate the total number of migrants onboard to have been between 720 and 750 persons. Survivors state that ‘in order to go from one place to another, you had to walk on people’. Most of the people were travelling on the bottom deck. There were several women and children in a separate, guarded room in the front of the middle deck. None survived. The witnesses also described the increasingly dire conditions over the course of the journey. The boat was lost, navigating without equipment, relying mainly on the position of the sun for orientation. The engine was overheating and malfunctioning, and supplies were running low, resulting in at least two people dying from dehydration before the capsizing even took place. The boat was in clear distress.

Mapping

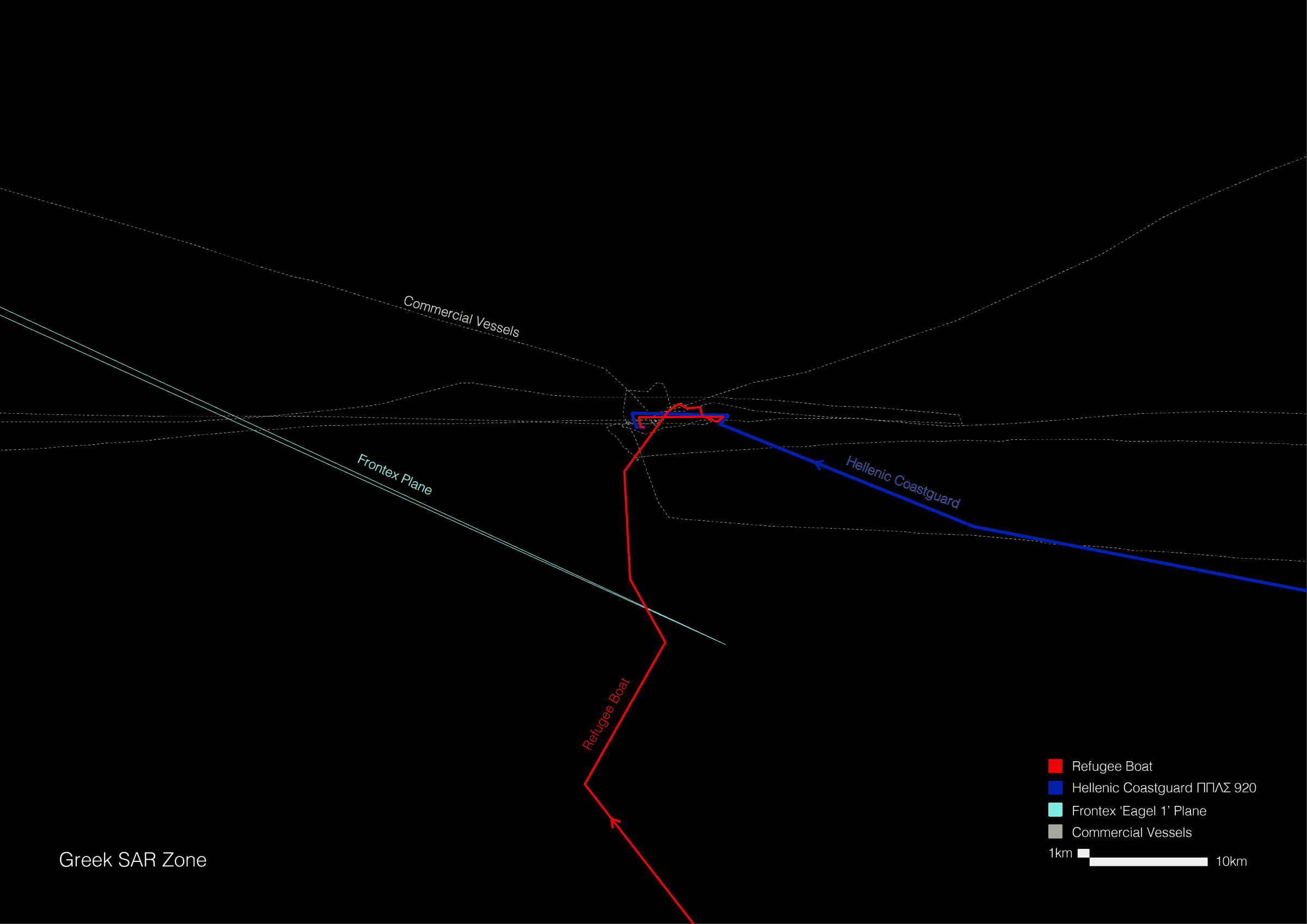

Our mapping of the incident identifies the location and direction of the migrant boat and the other boats sent to its location. This path reveals serious inconsistencies in the version of events as it was put forward by the HCG, especially in regards to the spatial data entered by the captain of the ΠΠΛΣ 920 in the vessel’s logbook.

According to the captain, between 23:57 and 01:40 the migrant boat moved westward, at a slow speed of approximately 3 knots. Analysis of the actual coordinates and times given by the HCG in the very same logbook suggest, however, that the speed and trajectory of the boat were incorrectly entered by the HCG captain.

Our analysis shows that between 23:57 and 00:44 the migrant boat travelled 3.88nm, at an average speed of 4.95 knots, higher than the speed of 3 knots indicated in the logs of the HCG. This is the highest recorded speed for the migrant boat that day, which could indicate that it was attempting to follow the faster boat being operated by the HCG.

This westward move is consistent with survivors’ accounts reporting that they were approached by the HCG and were told to follow their boat to Italian waters, where they would be handed over to the Italian Coast Guard. According to survivors, this escorting ‘to Italy’ continued for some time, until the engine of their boat stopped working.

Between 00:44 and 01:40 the vessel had almost come to a halt, turning south and covering only 0.56nm, at an average speed of 0.6 knots. The HCG logs fail to explain what happened during this one hour, during which they falsely reported that the vessel was still heading westwards at a ‘slow speed’.

The Towing

According to survivors, when their boat’s engine stopped, the HCG vessel approached their boat, with their stern touching its bow. A masked man climbed onto their boat and tied a rope to their railing off-centre, to the right.

They then tried to tow the migrant boat twice. Both attempts lasted, according to the migrants we interviewed, between a few seconds and a few minutes. The first time, the rope snapped. The second time, using the same rope, the HCG pulled away even faster, causing the migrant boat to rock to the right, then to the left, then to the right again, and eventually capsizing to the right (starboard). A group of witnesses who were sitting inside did not see the towing, but testified that they felt themselves being propelled forward ‘like a rocket’ long after their engine had stopped working. At 02:06, the HCG log notes that the migrant boat started sinking.

After capsizing, the boat turned upside down, and survivors climbed onto the hull, which was above the water’s surface for a few minutes. At this time, the ΠΠΛΣ 920 departed the scene, creating large waves in its wake that made swimming difficult and, according to survivors, further accelerated the sinking of the boat. Survivors recount that the HCG travelled and remained a considerable distance from their boat, directing its lights towards the people adrift in the water. Numerous individuals from the migrant boat attempted to swim to the HCG boat unsuccessfully. After approximately 20-30 minutes, once the boat had completely sunk, the HCG sent a small Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB) and started looking for survivors.

Findings

Our analysis strongly suggests that the Hellenic Coast Guard bears crucial responsibility for the shipwreck, illustrated by the following actions:

- Suggesting to the migrant boat that it travel westwards towards Italy and away from Greece’s SAR zone, despite the fact that the boat was in clear distress and should have been given the opportunity to dock at the nearest safe port, which would have been in Greece.

- Neglecting to respond to repeated Frontex offers to send aerial surveillance aircrafts to the scene.

- Failing to mobilise nearby assets and releasing commercial ships from their duty of rescue, despite there not being enough space on the HCG vessel for all the migrants in case of their boat capsizing.

- Towing the overcrowded migrant boat, resulting in its capsizing.

- Retreating from the scene after the migrant boat capsized in such a way that created waves, which in turn made survival in the open sea more difficult; and leaving survivors to fend for themselves at sea for a period of 20-30 minutes for no apparent reason.

Our analysis also suggests a strong likelihood that the HCG attempted to distort the narrative around the event by:

- Not activating the cameras and the AIS tracking in the vessel they sent to the scene, or otherwise concealing the material these devices would have recorded.

- Confiscating migrant phones containing videos that might shed light on the events leading up to the capsizing.

- Providing inaccurate and conflicting information regarding the migrant vessel’s location and speed.

In line with the survivors’ quest for justice, we will ensure the findings of this investigation be made available to all independent bodies seeking accountability for this deadly incident—an event which demonstrates once again the inhumane and lethal nature of the European border regime.