Date of Incident

Publication Date

Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Methodologies

Forums

Read the full report: Humanitarian Violence: Israel’s Abuse of Preventative Measures in its 2023-2024 Genocidal Military Campaign in the Occupied Gaza Strip

Editor’s note: throughout our analysis of Israeli evacuation orders, we frequently refer to ‘north’ and ‘south’ in quotes, to indicate that these are designations imposed by Israel that fluctuate according to the Israeli military agenda and do not correspond to the geography of the Gaza Strip recognised by its Palestinian residents. Similarly, we refer to ‘safe routes’ and ‘safe zones’ in quotes to reflect that they are neither safe nor implemented in accordance with their clear definitions under international law. ‘Evacuation orders’ likewise have not been executed in compliance with international law, and therefore what is referred to here as ‘evacuation orders’ does not in fact meet the legal criteria for the correct application of this humanitarian measure.

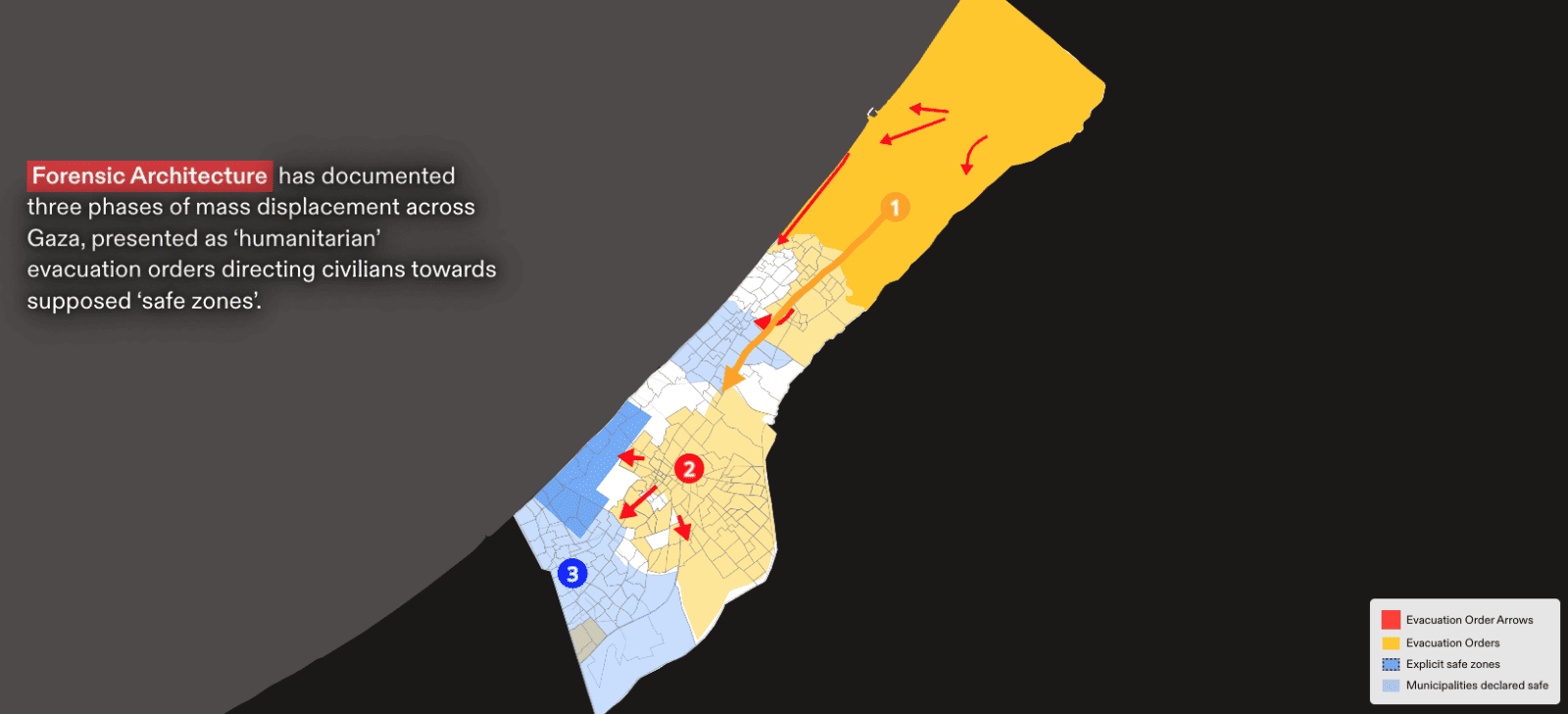

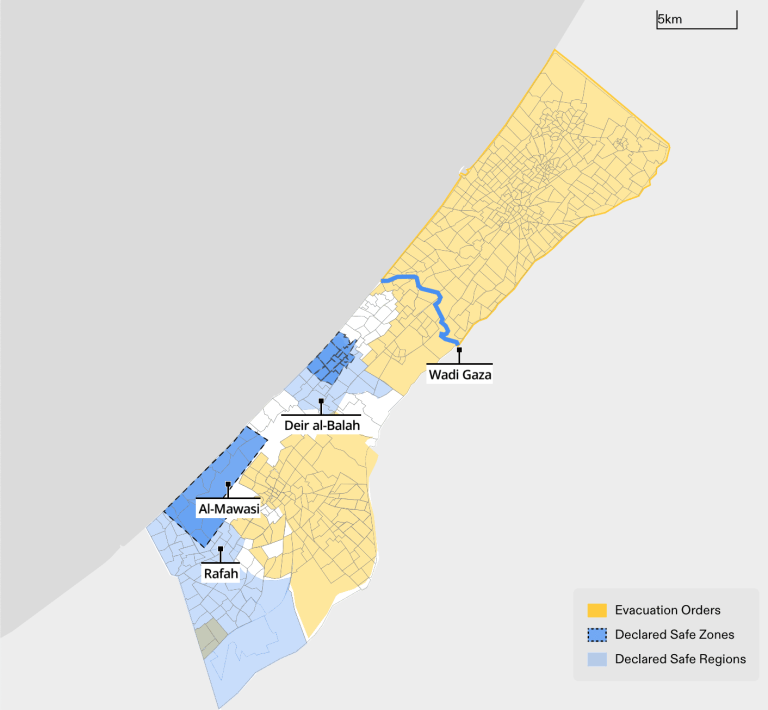

Since 7 October 2023, Forensic Architecture has documented the mass displacement of Palestinian civilians being carried out by the Israeli military in the Gaza Strip, and identified three overlapping phases in its execution. Across all three phases, the Israeli military has repeatedly abused the humanitarian measures of evacuation orders, ‘safe routes’, and ‘safe zones’, and failed to comply with the laws governing their application within a wartime context. These patterns of systematic violence and destruction have forced Palestinian civilians from one unsafe area to the next, confirming the conclusion echoed across civilian testimonies, media reports, and assessments by the UN and other humanitarian aid organisations, that ‘there is no safe place in Gaza’.

Phases of Mass Displacement

Phase 1: Mass displacement from ‘north’ to ‘south’

13 October – 24 November 2023

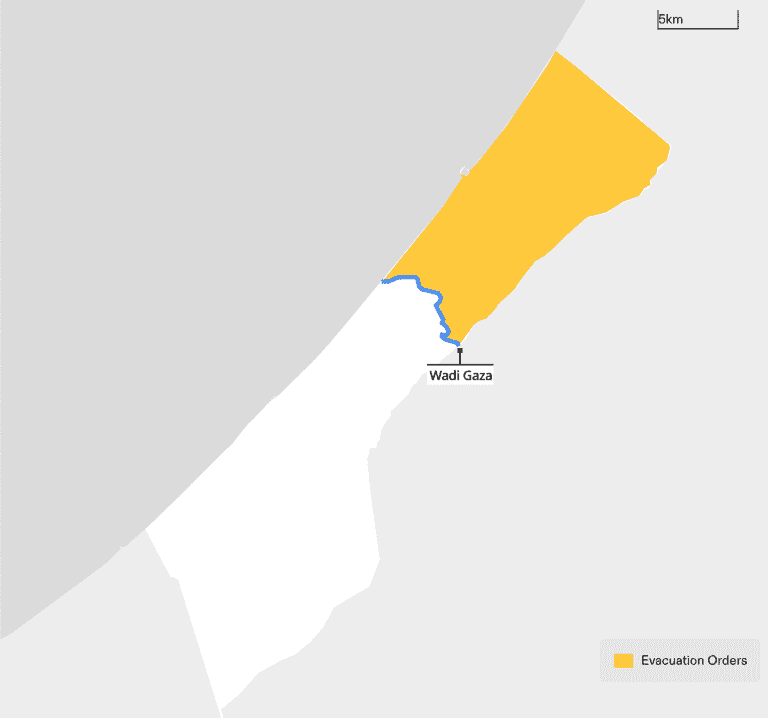

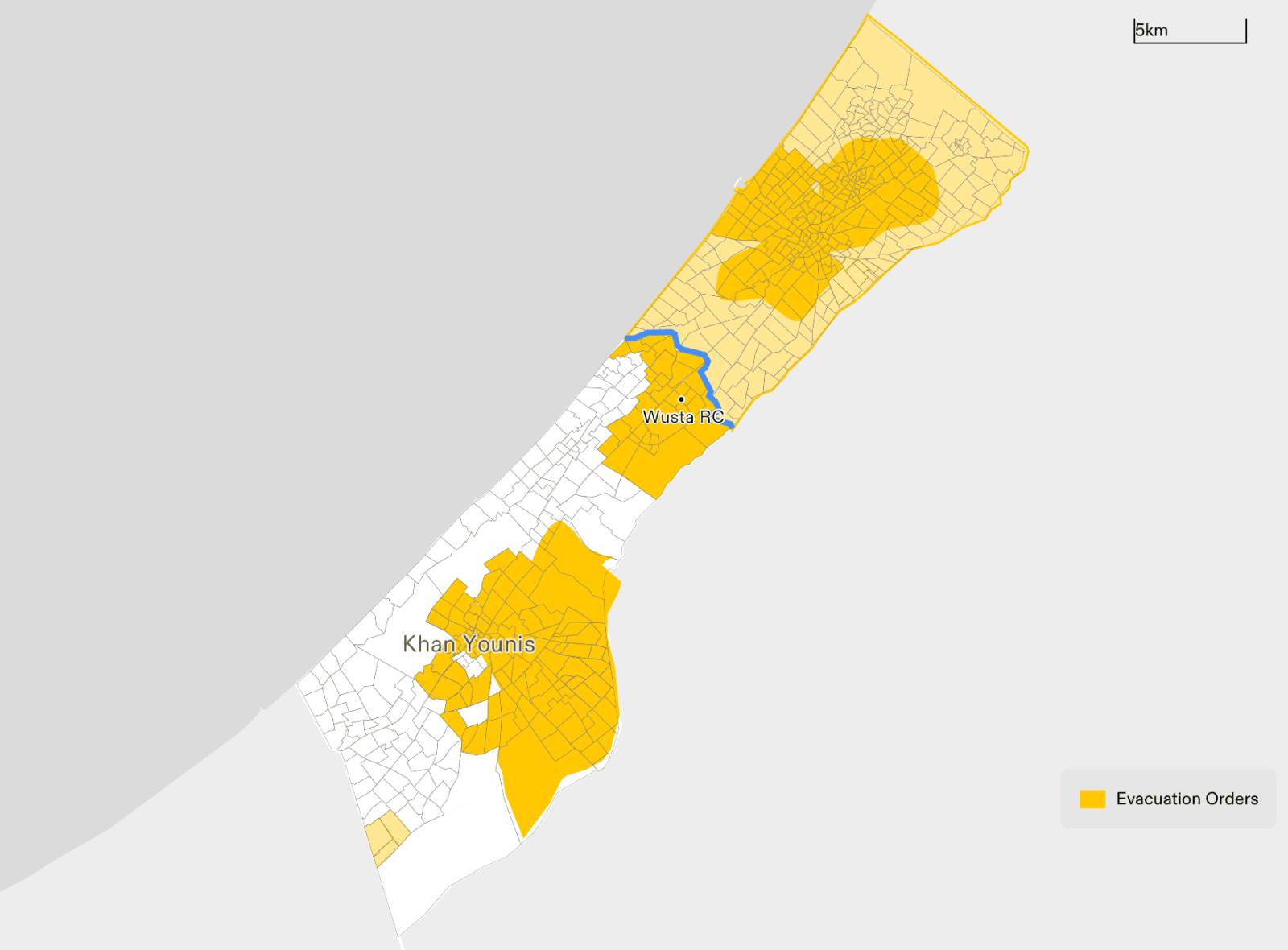

We locate this first phase of displacement as beginning on 13 October 2023, when the Israeli military issued an order for ‘the entire population of the Gaza Strip north of Wadi Gaza’ (around 1.1 million Palestinians) to evacuate and relocate to the ‘south’ within 24 hours.

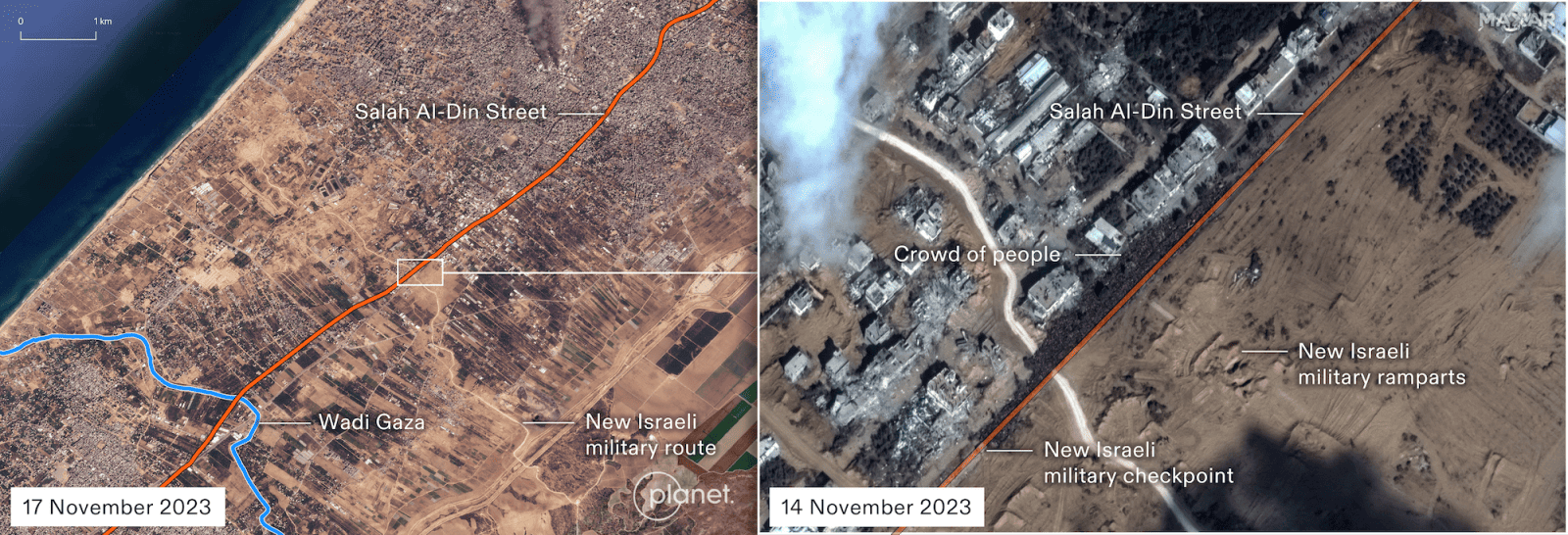

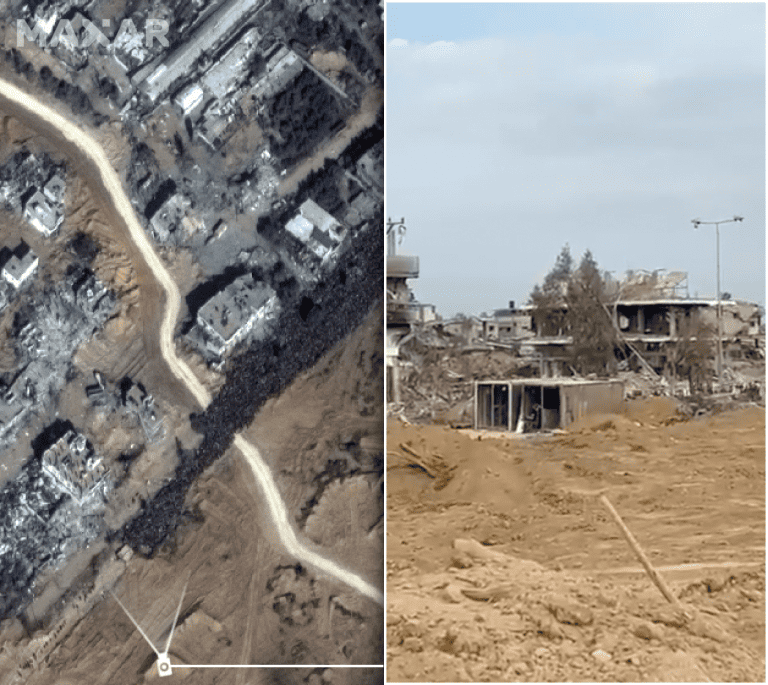

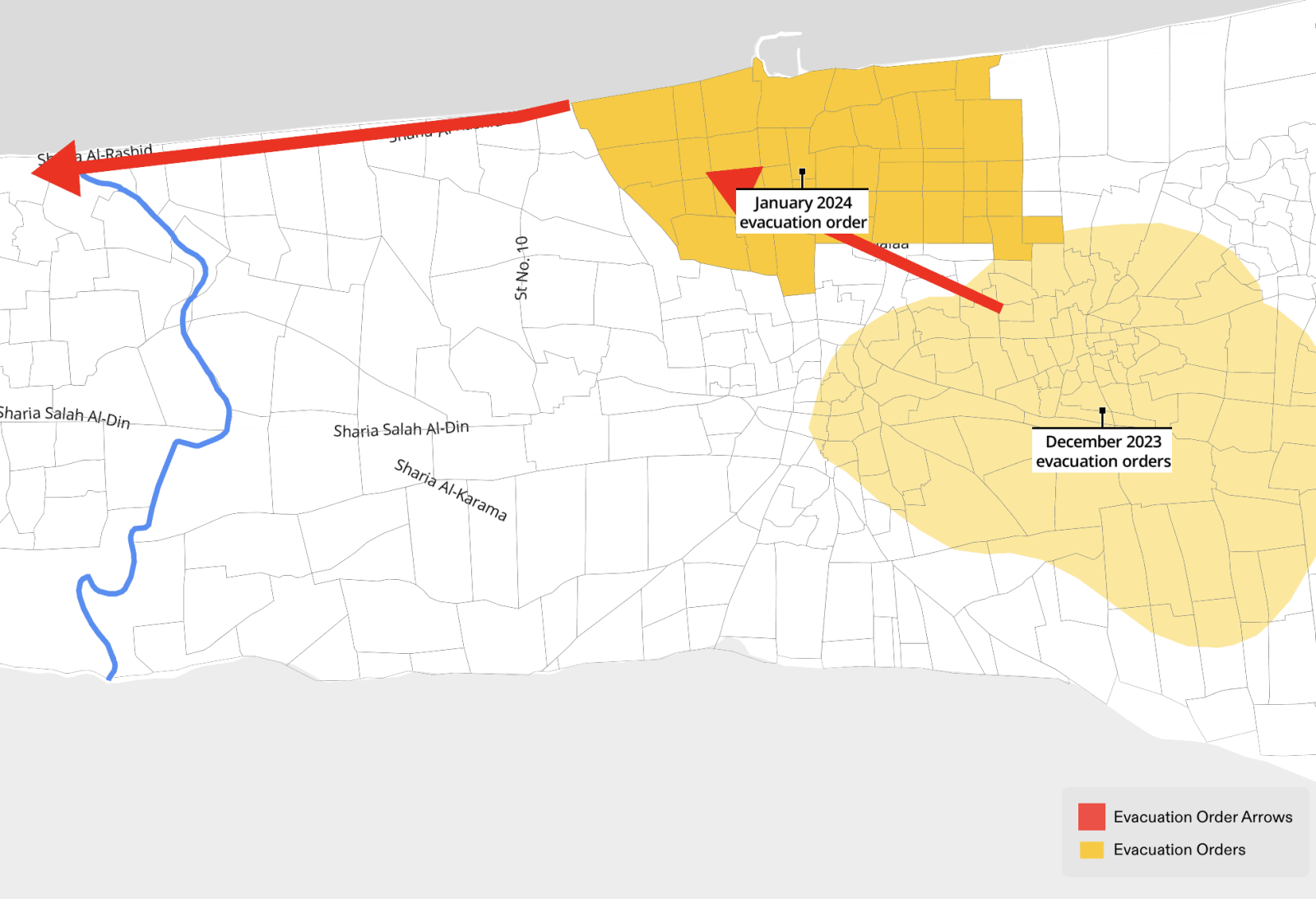

Our analysis of satellite imagery reveals that across several weeks in early November the Israeli army carved an east-to-west military route through the lived fabric of the Gaza Strip. The new route was 3km north of Wadi Gaza and functioned as a makeshift, militarised border demarcating a new north/south divide (Figure 2). A military checkpoint was set up at the intersection of this border line and Salah al-Din Street, Gaza’s main traffic artery and the sole evacuation route at this time. Palestinians attempting to move south along this route found themselves surrounded by snipers upon arrival at this checkpoint, and reportedly were ordered by megaphone, under threat of warning shots and arrests, to disrobe for searches and to face cameras, presumably for the gathering of biometric data. As of 14 March 2024, displaced Palestinians have not been permitted by the Israeli military to return ‘north’ since October, not even during the November ceasefire. Civilians who have attempted to cross back through the checkpoint have reportedly been shot at, some fatally.

Phase 2: The Evacuation Grid

1 December 2023 – ongoing

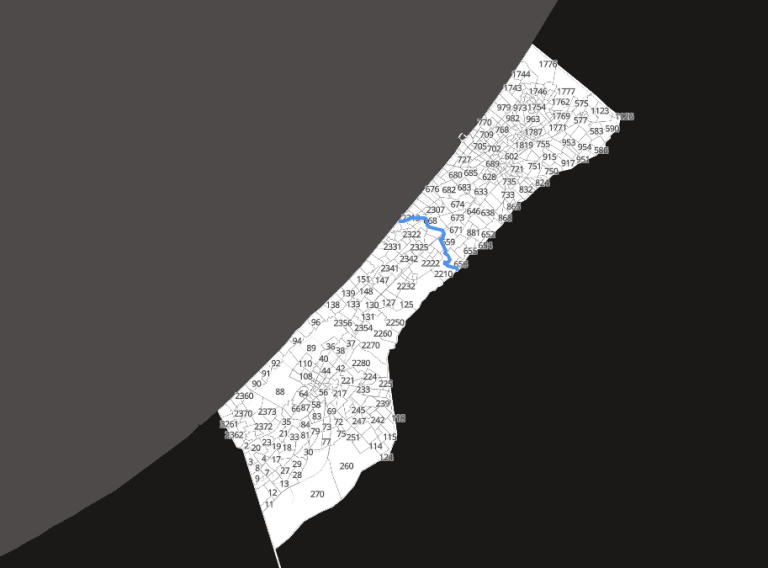

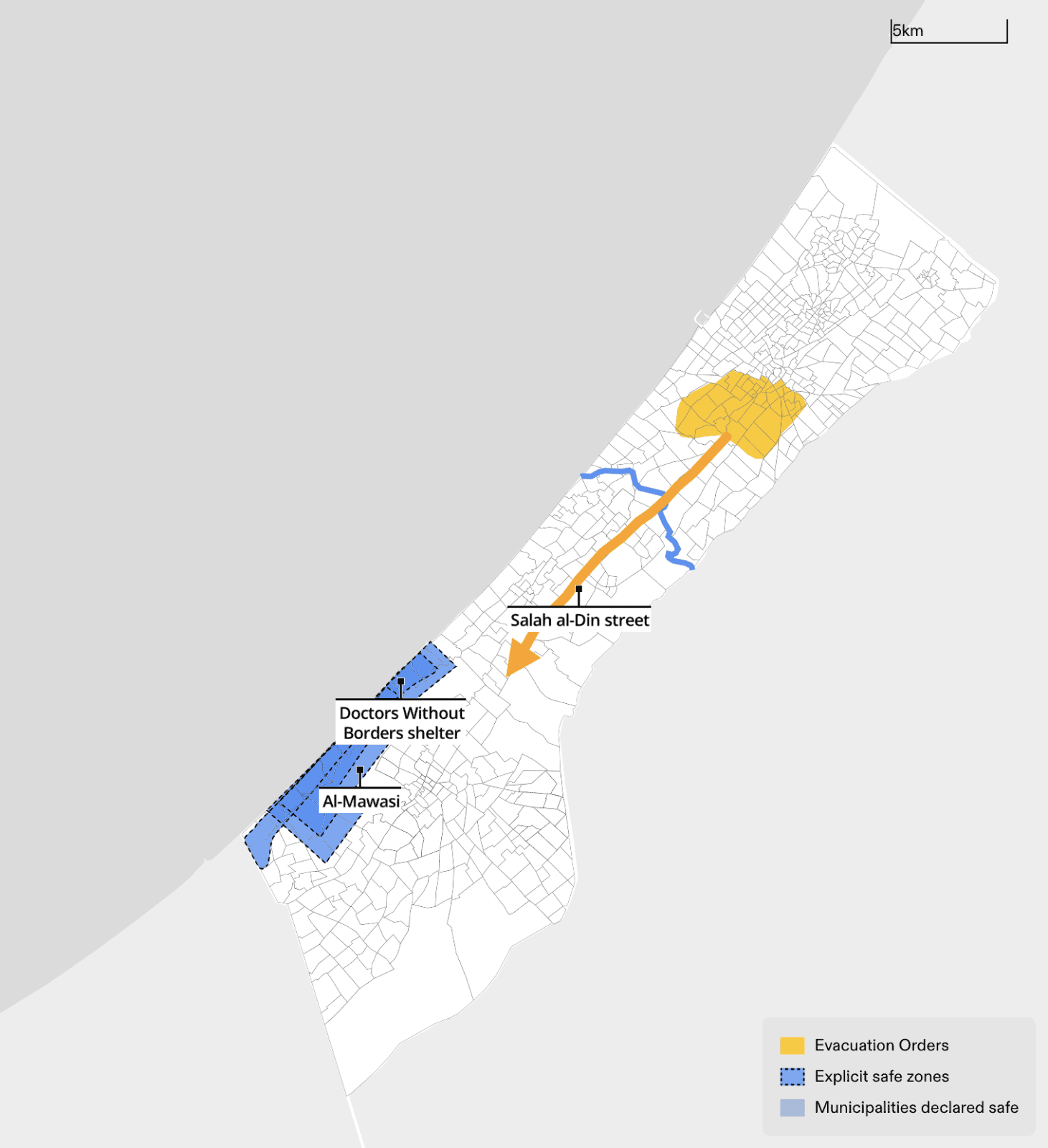

On 1 December 2023, the Israeli military introduced an interactive grid-based evacuation map that divided Gaza into 623 blocks. Using this evacuation grid, the military began ordering Palestinians in areas throughout Gaza, including south of Wadi Gaza—such as Khan Younis and the refugee camps in central Gaza—to evacuate.

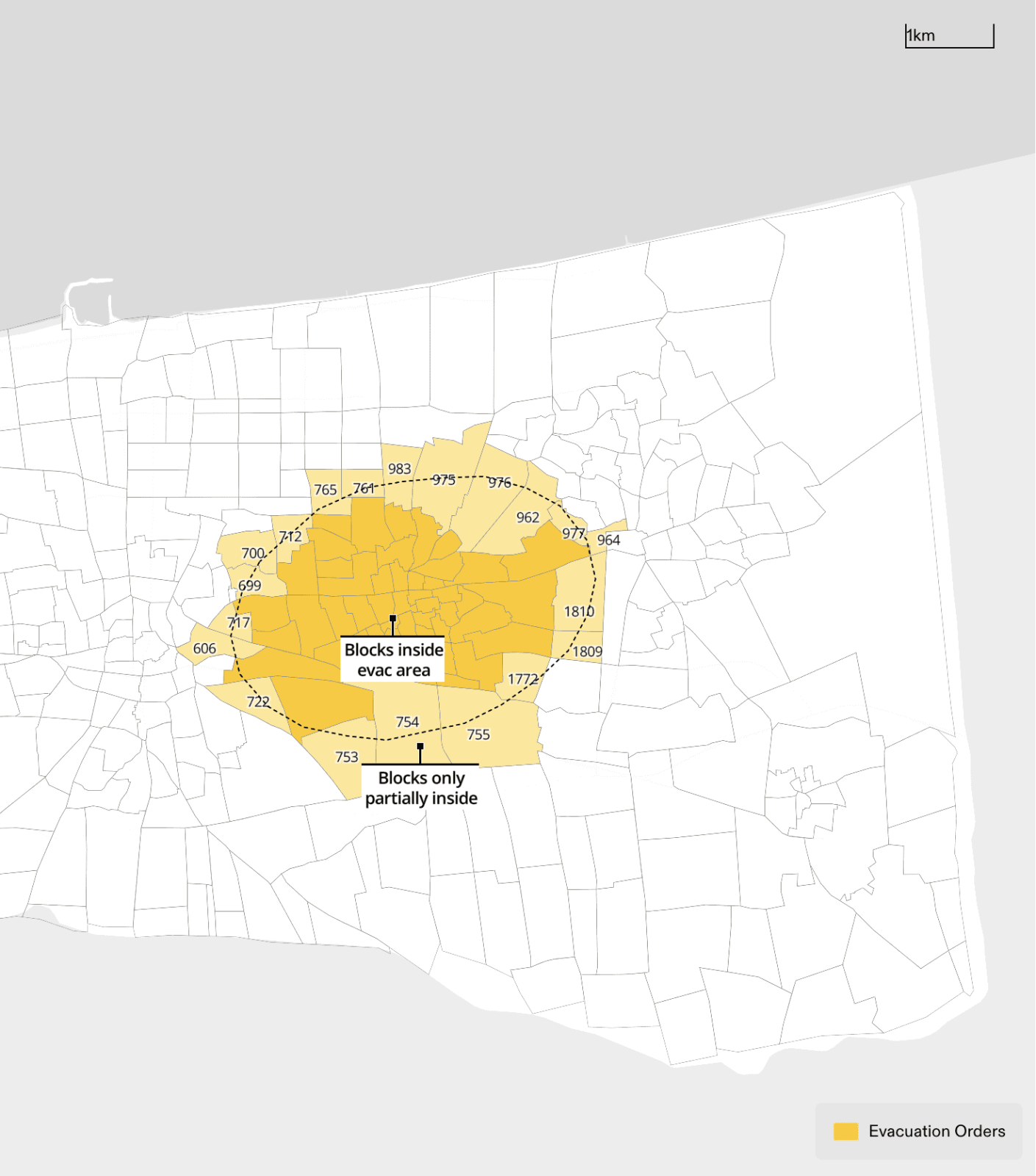

The ‘evacuation orders’ issued referencing this grid have been imprecise, inconsistent, and sometimes even contradictory, leading to panic and confusion among the civilian population about which areas should be evacuated. For example, across nine different ‘evacuation orders’, the shaded areas designating ‘evacuation zones’ (areas highlighted in a map and instructed to evacuate) did not correspond with the blocks in the evacuation grid (Figure 6). Instead, the ‘evacuation zones’ followed a different logic to that of the grid, resulting in some blocks on the grid being only partially included in the designated zones. This has produced further uncertainty among Palestinian residents in or near those areas about how to correctly interpret these maps and the boundaries of the ‘zones’ depicted within them.

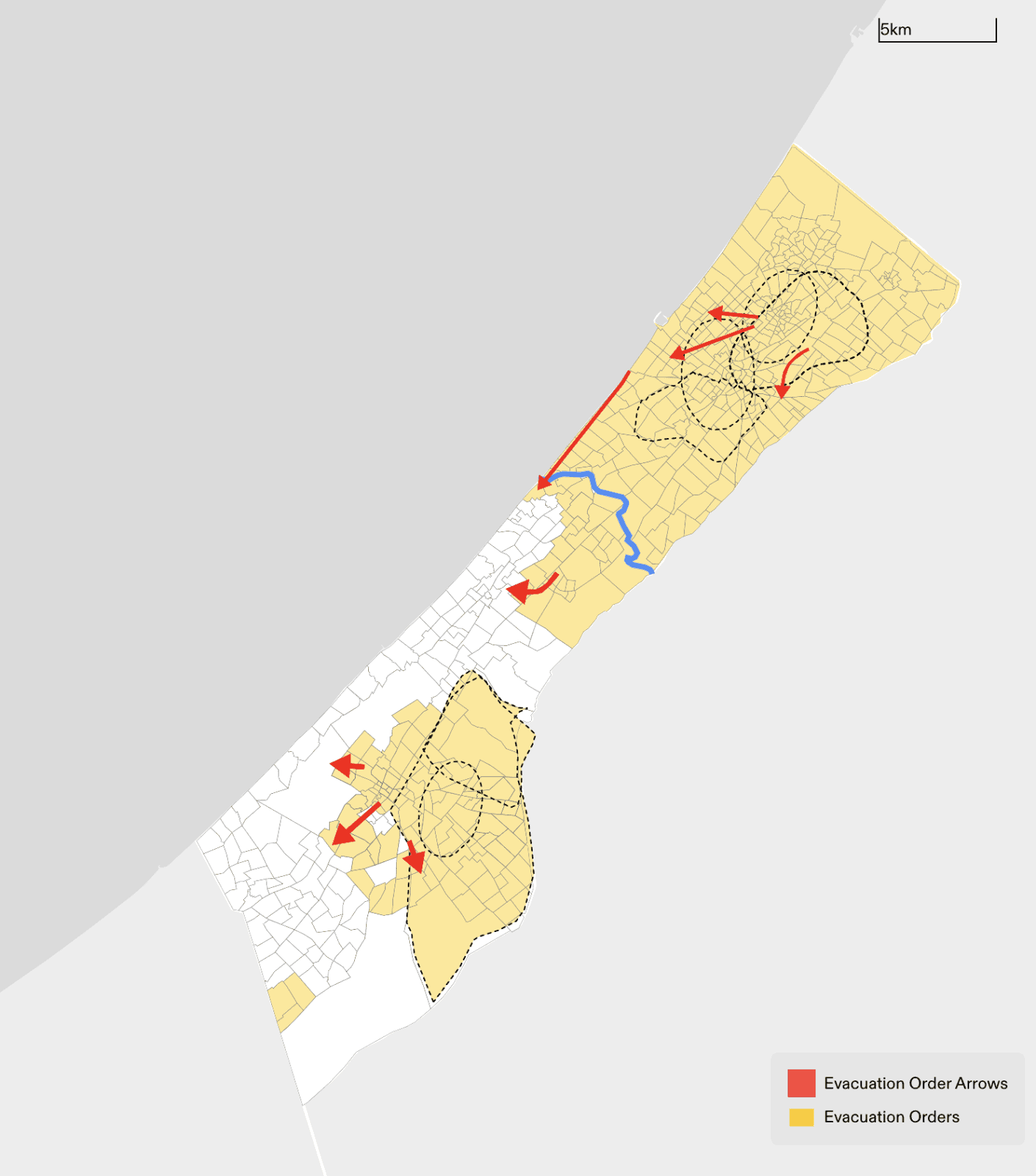

While on a case-by-case basis the evacuation orders may appear poorly designed and even careless, when viewed collectively, they evidence systematic forced displacement at a mass scale, whereby Palestinians have been progressively pushed into areas further and further south that are subsequently subject to attack or evacuation or both. As the areas ordered to evacuate have expanded, the Israeli ground invasion has advanced. Rather than deploying these ‘humanitarian measures’ as a means of protecting civilian life, Israel has instead amplified the risk to civilian life, unequivocally failing to comply with the laws that govern their implementation and to provide adequate justification for their military necessity.

Phase 3: Mass displacement from ‘safe zones’

22 January 2024 – ongoing

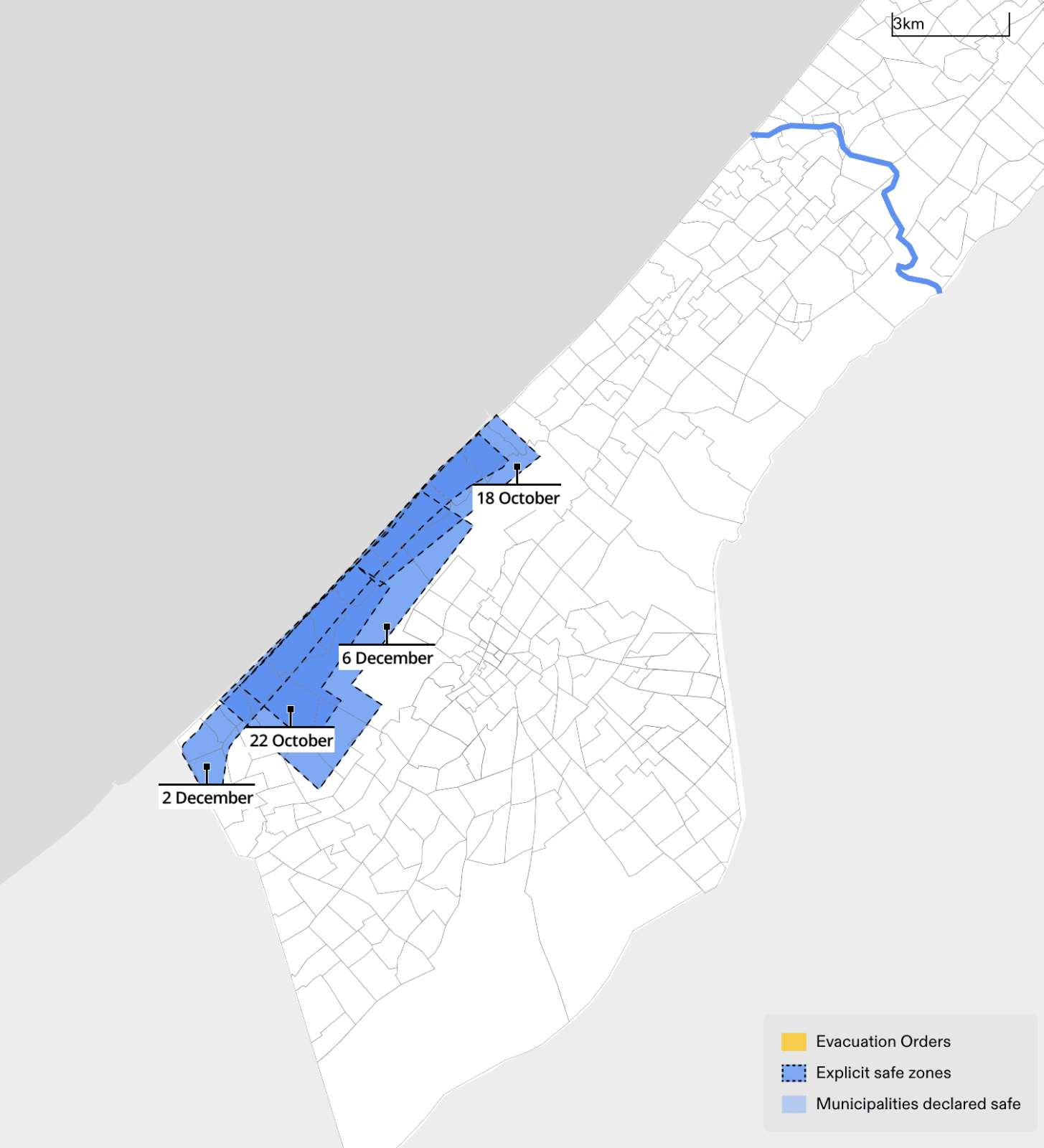

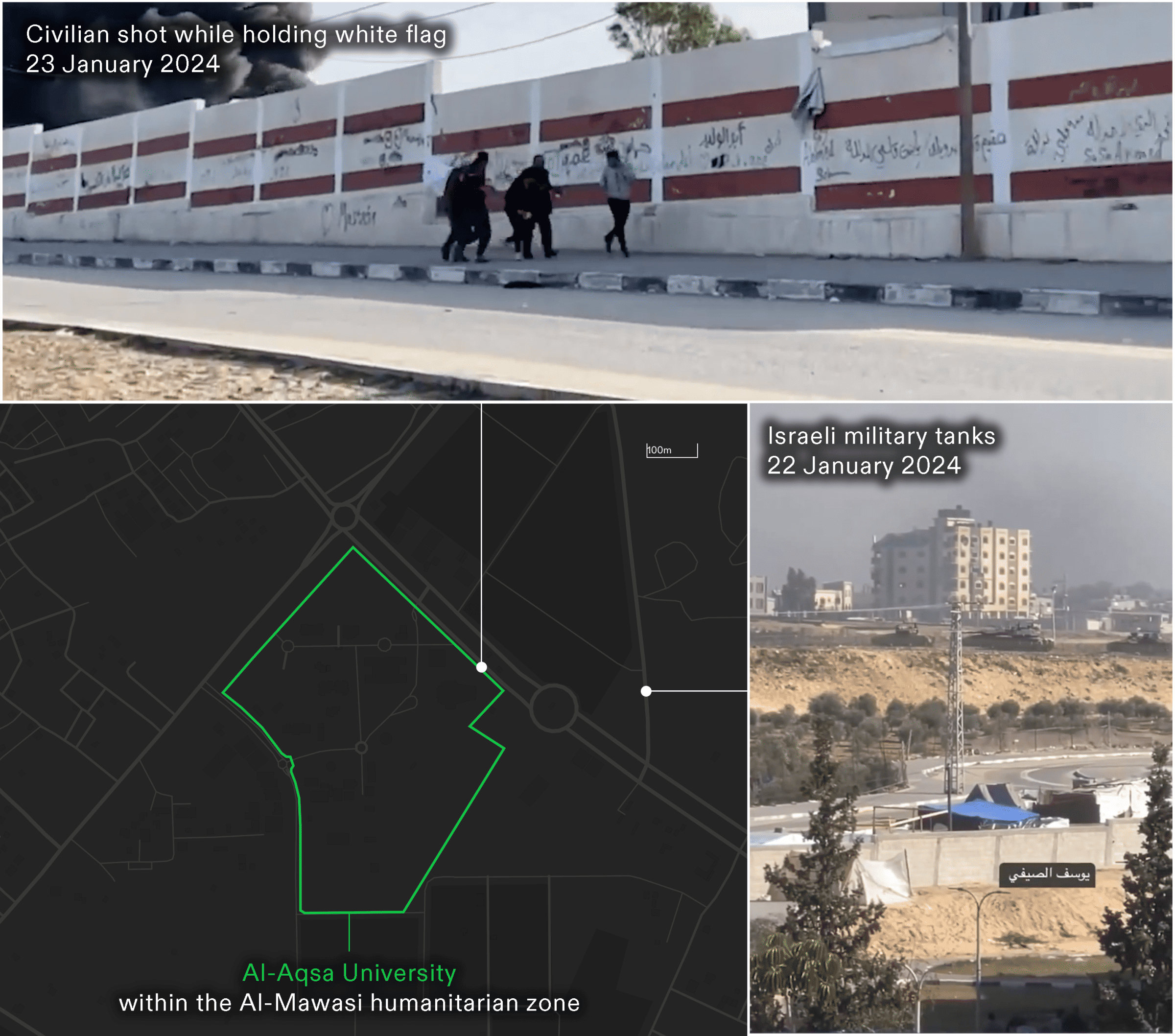

Satellite imagery reveals that throughout January, thousands of Palestinians sought refuge in al-Aqsa University, located within the designated ‘Mawasi Humanitarian Zone’. On 22 January, the Israeli army invaded this ‘humanitarian zone’; by 29 January, updated satellite imagery showed that the Israeli army had demolished the dense camp of tents on the Aqsa University campus. Satellite images from the same day show displaced Palestinians stopped at a makeshift checkpoint in al-Mawasi, revealing ‘safe zones’ as a tool for tightening Israeli control over the displaced. Attacks on the ‘safe zones’, including Rafah, have escalated in the last few weeks.

Abuse and Weaponisation of ‘Evacuation Orders’ at Large to Facilitate Mass Displacement, Fatalities, and Genocidal Acts

‘Evacuation orders’ to areas that were already subject to ‘evacuation orders’

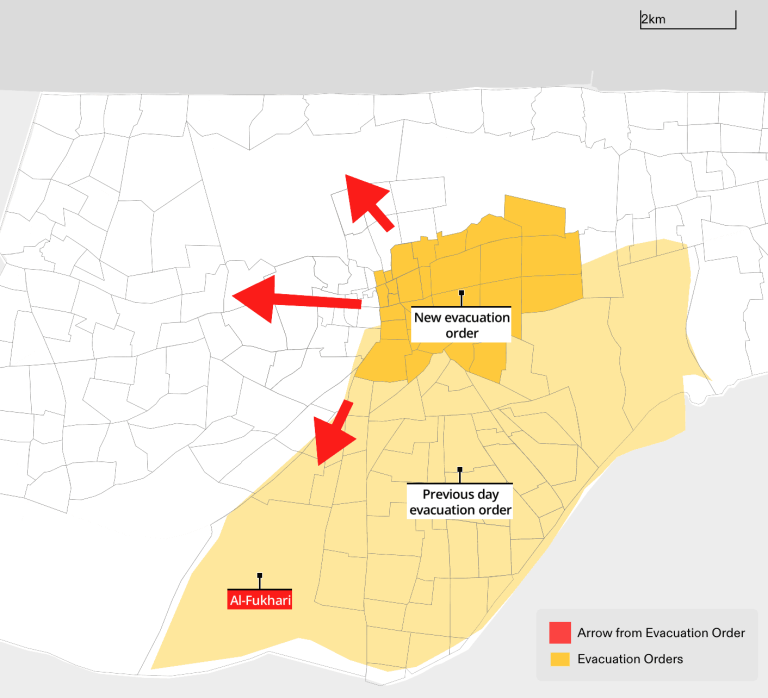

In some instances, Palestinians in Gaza were directed to evacuate to areas that had themselves received ‘evacuation orders’ less than 24 hours prior. For instance, on 2 December 2023, multiple regions were ordered to evacuate and relocate, including al-Fukhari. Subsequently, on 3 December, zones in central Khan Younis were instructed by the Israeli military to evacuate and relocate to al-Shaboura, Tel al-Sultan, and al-Fukhari—the latter of which had already been ordered to evacuate (see Figure 10).

Ground invasion of areas that had not yet received ‘evacuation orders’

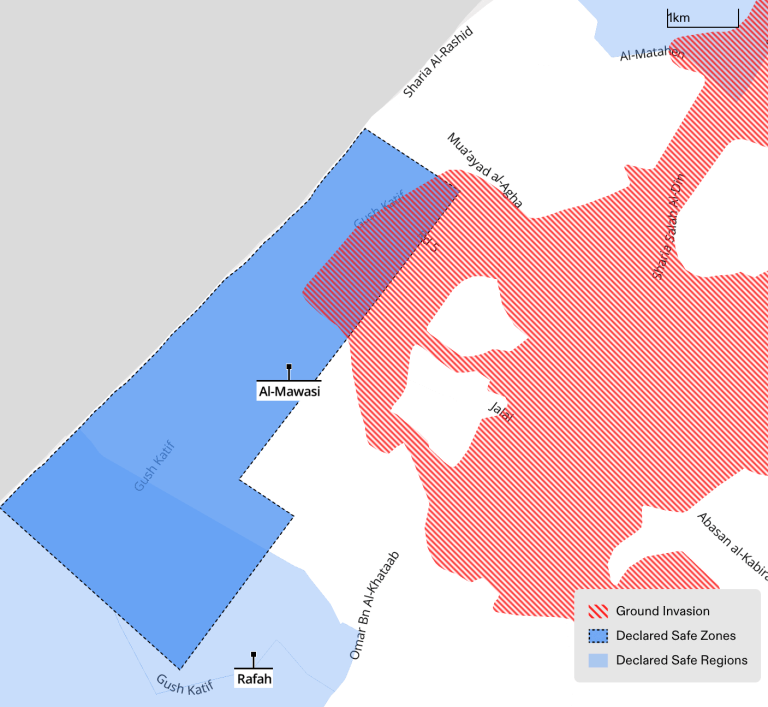

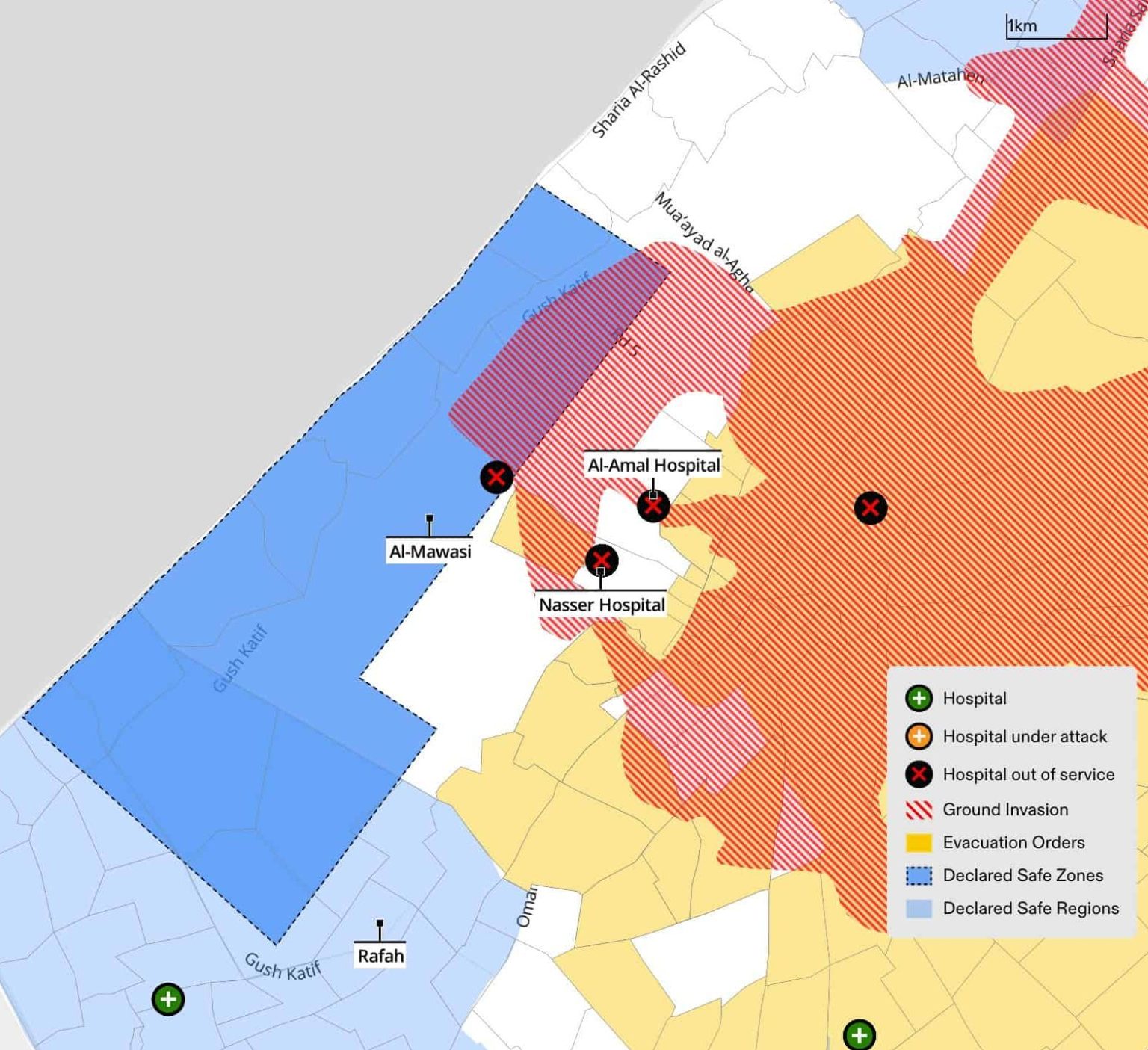

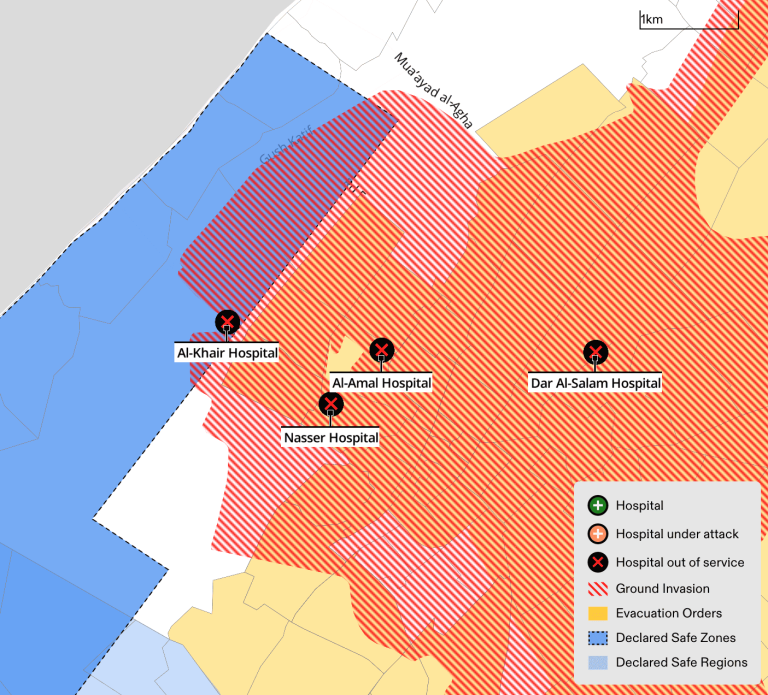

Our analysis reveals that a ground invasion of al-Mawasi and the central part of Khan Younis city had already commenced on 22 January 2024, even though neither of these areas had received any ‘evacuation orders’ at that time. While an ‘evacuation order’ was issued subsequently for the centre of Khan Younis on 23 January 2024, after the ground invasion of the area had already begun, at the time of writing al-Mawasi has yet to receive a formal ‘evacuation order’ and is still designated as a ‘safe zone’—despite being subject to attack. The order for Khan Younis came only after the military siege on Nasser and al-Amal Hospitals (see Figure 11) and the reported attack on Khalidiya school—also located in Khan Younis—that was acting as a shelter for displaced civilians.

Unspecified durations for ‘evacuation orders’

Our study revealed numerous cases where the timeline of the ‘evacuation orders’ was unclear, with certain areas receiving the same directive multiple times. It was not clear to individuals residing or sheltering in these areas when the ‘evacuation order’ should be thought to expire, or if it was safe for residents to return to the areas in question. The area of al-Nusairat camp, for instance, received multiple ‘evacuation orders’ during the period of 22 December 2023 to 8 January 2024, triggering significant displacement towards the designated ‘safe zones’ in Deir al-Balah and Rafah. A combination of subsequent attacks on these ‘safe zones’ and the absence of additional ‘evacuation orders’ for al-Nusairat led displaced families to believe they could safely return to their homes in February 2024. However, in early February the Israeli military conducted a series of airstrikes in these areas again, resulting in civilian casualties among those who had returned. Using witness testimony and footage, Forensic Architecture verified the killing of two Palestinian women on 10 February 2024, just a few days after they had returned to al-Nusairat from Rafah.

Patterns of consecutive displacement

In our analysis, we observed that ‘evacuation orders’ have facilitated multiple sequential and consecutive displacements. During the different phases of ‘evacuation orders’, Palestinians in Gaza were instructed to evacuate to areas that received their own ‘evacuation order’. For instance, as part of the first phase of ‘evacuation orders’, the Israeli army ordered that the entire population north of Wadi Gaza relocate ‘south’, to areas including Khan Younis and Nusairat. Subsequently in December 2023, the Israeli army began using the ‘evacuation grid’ to instruct Palestinians in those same ‘southern’ areas to relocate even further south to ‘safe zones’ including Rafah—which has itself since come under attack and remains under threat of ground invasion. During Phase 2 of the ‘evacuation orders’, on 8 December 2023, residents of Jabaliya, Shujaiyeh, Zaytoun, and the Old City of Gaza were instructed to evacuate towards the south-western part of Gaza City. On 29 January 2024, those same areas of south-western Gaza City received an ‘evacuation order’ instructing already displaced civilians to relocate once again towards Deir Al-Balah (see Figure 12).

‘Evacuation orders’ to areas subsequently attacked by the Israeli military

On the morning of 20 February 2024 at 09:29 am local time, the Israeli military published an ‘evacuation order’ for the neighbourhoods of al-Zaitoun and al-Turkman (see Figure 13). The order instructed Palestinians in these neighbourhoods to evacuate to the ‘Mawasi Humanitarian Zone’ via Salah al-Din Street. Approximately eleven hours later, online reports emerged about attacks in al-Mawasi overnight and further advancement of the Israeli ground operation in the area. As reported by al-Jazeera on 21 February, despite being designated as a ‘safe zone’ by the military, al-Mawasi came under heavy bombardment, with bulldozers on the ground and aerial strikes by attack drones causing a number of civilian fatalities and injuries. Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has reported that during the attack on 20 February 2024, an Israeli tank fired on a house sheltering MSF members and killed two members of their families. The Israeli military issued the same order on 21 February to the residents of al-Zaitoun and al-Turkman, instructing them to go to al-Mawasi even though the ‘safe zone’ there had been attacked, and Israeli tanks were still in the area.

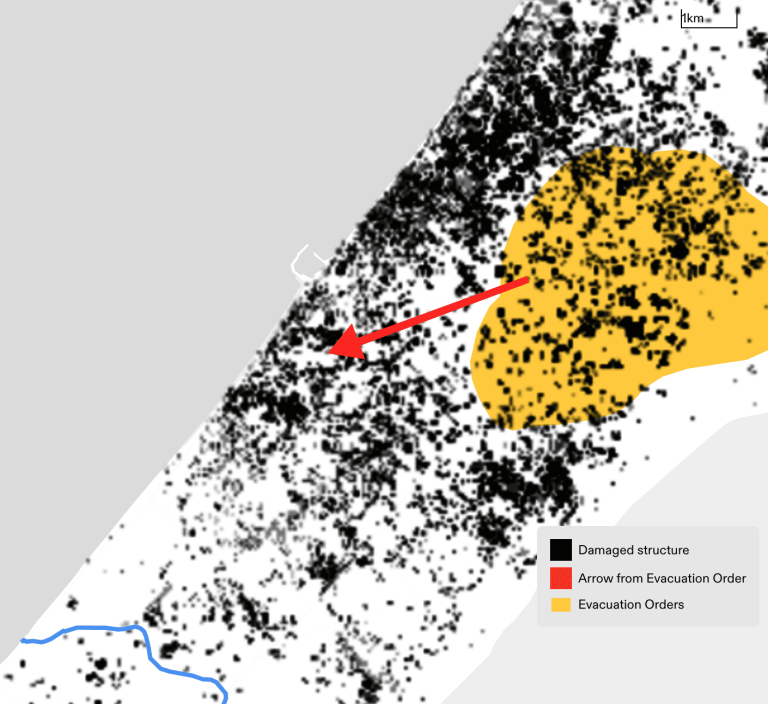

‘Evacuation orders’ to destroyed areas

Until the temporary ceasefire on 24 November 2023, as people were being instructed by the Israeli military to travel ‘south’, and while those who had been displaced in the south were being prevented by the army from returning north to reach their homes during the ceasefire, the same southern areas to which civilians were already displaced, and were repeatedly instructed to relocate to, continued to be targeted (Figure 14). Our analysis shows that during this period, by 7 January 2024, many of the areas to which people were being instructed to relocate using the Israeli military’s ‘evacuation grid’ were destroyed or severely damaged. For instance, on 8 December, when an Israeli military ‘evacuation order’ (Figure 12) instructed residents of Jabaliya, Shujaiyeh, Zaytoun, and the Old City of Gaza to evacuate towards the western part of Gaza City, this area was already largely destroyed (see Figure 15).

The Fallacy of ‘Safe Zones’ and ‘Safe Routes’

Boundaries of ‘safe zones’: Elastic, unclear and inconsistent

The boundaries of various ‘safe zones’ have not been clearly defined or effectively communicated, neither to Palestinian civilians seeking safety in Gaza nor to the general public, including human rights investigators monitoring attacks on these ‘safe zones’ (see Figure 16).

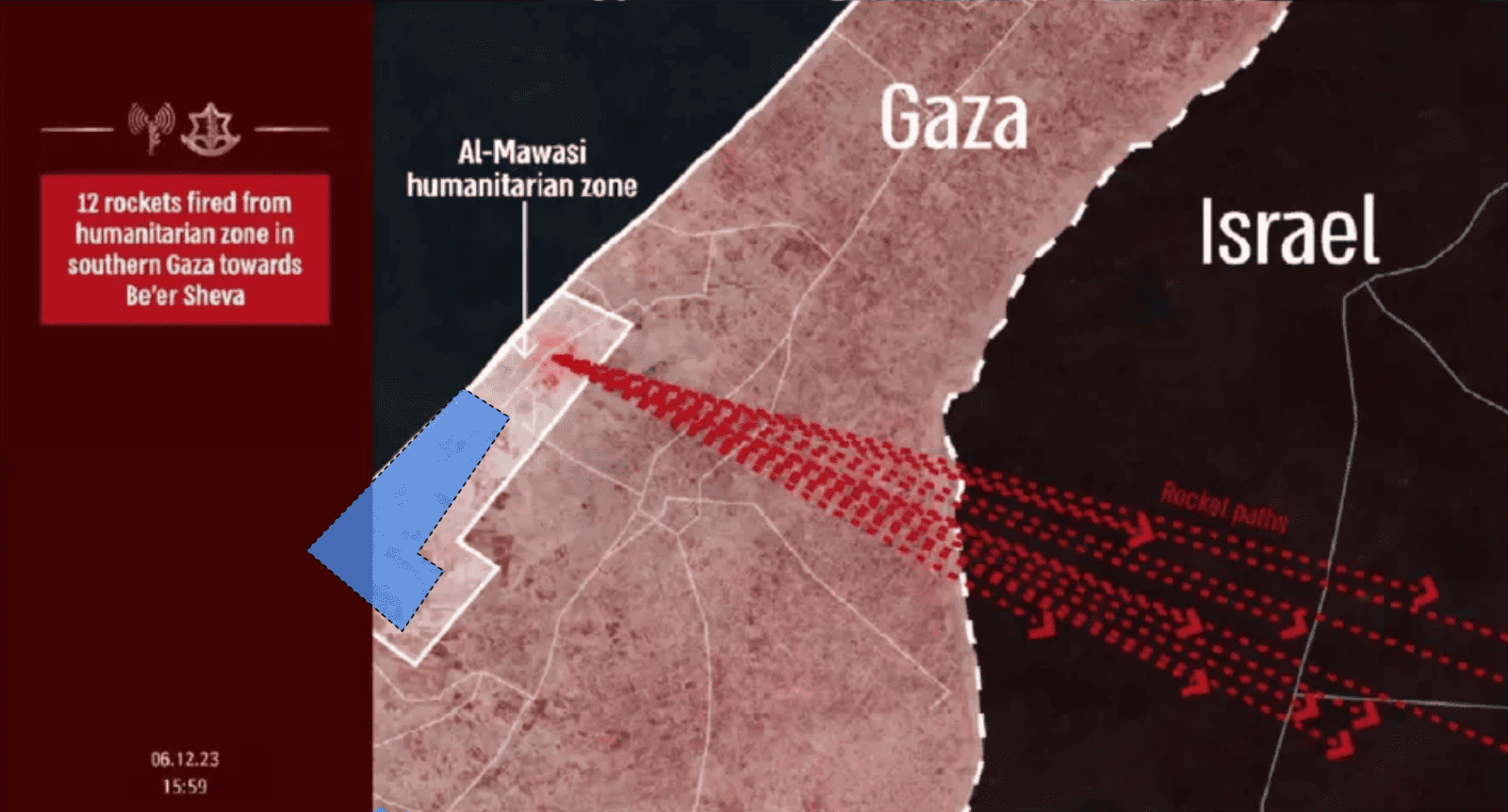

An illustrative instance of the ambiguous and elastic boundaries delineating ‘safe zones’ is evident in the case of the Mawasi area west of Khan Younis.

The size and borders of this zone, as conveyed by the Israeli military, have fluctuated multiple times. Notably, its boundaries are rendered as significantly more expansive in publications where the Israeli military makes claims regarding the alleged use of these ‘safe zones’ as part of Palestinian armed resistance (Figure 17). In contrast, when Palestinians are instructed to take refuge in the ‘safe zone’ of al-Mawasi, its boundaries encompass a visibly smaller area. In other words, the boundary operates flexibly to support Israeli narratives about its humanitarian and military measures, rather than to establish consistent boundaries for ensuring safe refuge.

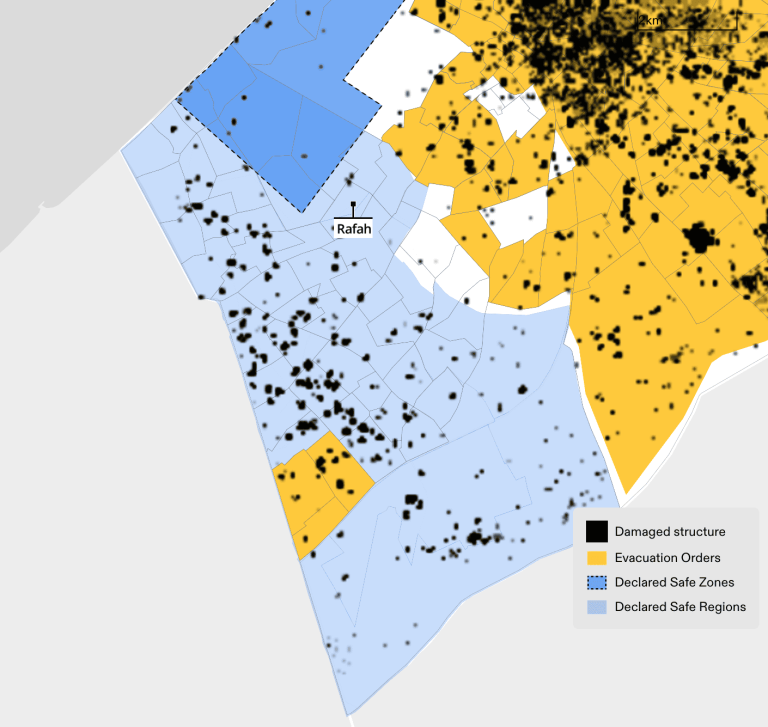

Moreover, multiple ‘evacuation orders’ instructed civilians to relocate to Rafah without providing explicit boundaries for ‘safe areas’ within the city. Some orders explicitly refer to neighbourhoods in Rafah—’al-Shaboura’, ‘al-Sultan’, and ‘al-Zohour’—as ‘known shelters’, as if to suggest that their status and bounds as ‘shelters’ were already known, waiving the need for clarification.

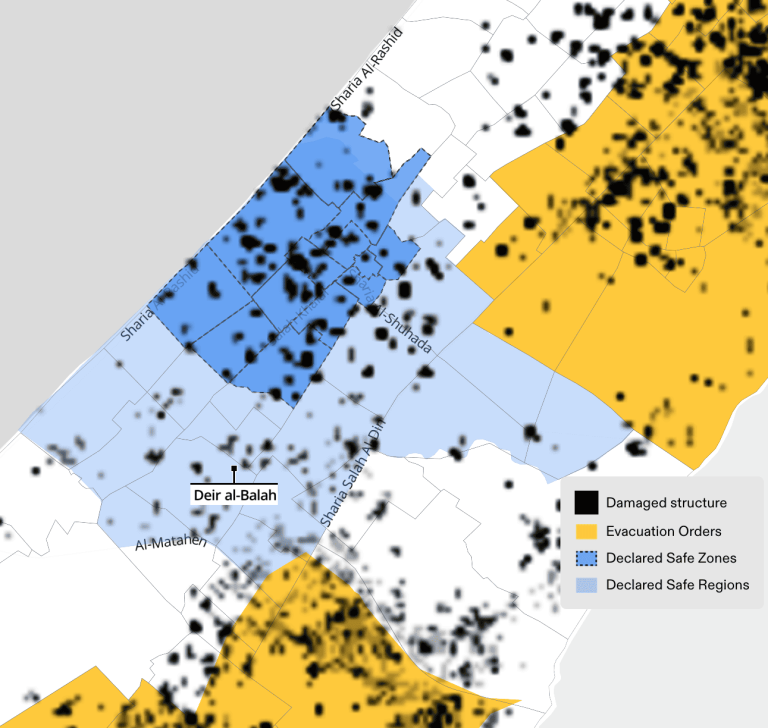

Multiple ‘evacuation orders’ also instructed civilians to relocate to Deir al-Balah. None of these orders provided explicit boundaries for specific ‘safe zones’ within the city—except for one we identified that uses the numbered block system of the aforementioned ‘evacuation grid’ to mark certain blocks within Deir al-Balah as ‘safe’.

Direct attacks on designated ‘safe zones’ and ‘safe routes’

On 13 October 2023—the same day it had been declared a ‘safe route’ for displaced civilians moving south—Salah al-Din Street was the target of an Israeli airstrike that hit a civilian convoy and reportedly killed seventy. Ground and aerial attacks on this evacuation route and widespread destruction around it, including in areas south of Wadi Gaza, evidence the danger of Israel’s own designated ‘safe routes’.

Our analysis confirms numerous instances of Israeli military attacks on ‘safe zones’ in al-Mawasi, Deir al-Balah and Rafah. At least two such attacks have occurred since Phase 2 of the ‘evacuation orders’, which began on 1 December.

Forensic Architecture has verified a case in which the Israeli military shot at a Palestinian civilian holding a white flag, close to al-Aqsa university inside the ‘Mawasi Humanitarian Zone’ on 23 January 2024 (see Figure 19). This case was further analysed by the investigative agency Earshot, who verified the location of the Israeli tanks from which this civilian was targeted.

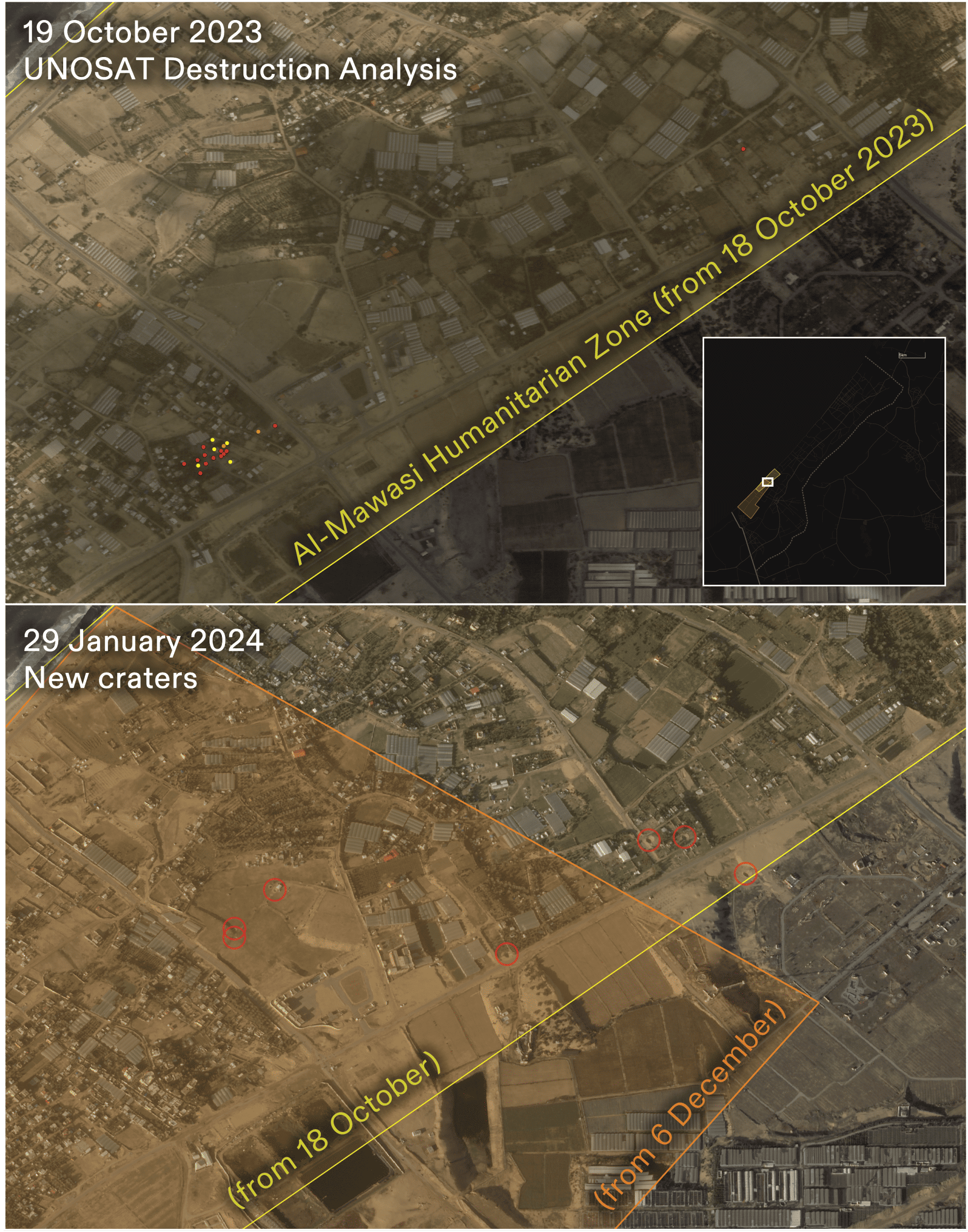

Moreover, a comparison of satellite imagery of the al-Mawasi ‘humanitarian zone’ from 19 October 2023 and from 29 January 2024 reveals numerous craters in this ‘safe zone, indicative of military activity (see Figure 20). These signs of destruction appeared during a period in which the Israeli military had made multiple announcements referring to al-Mawasi as a ‘humanitarian zone’ and a safe refuge for Palestinians.

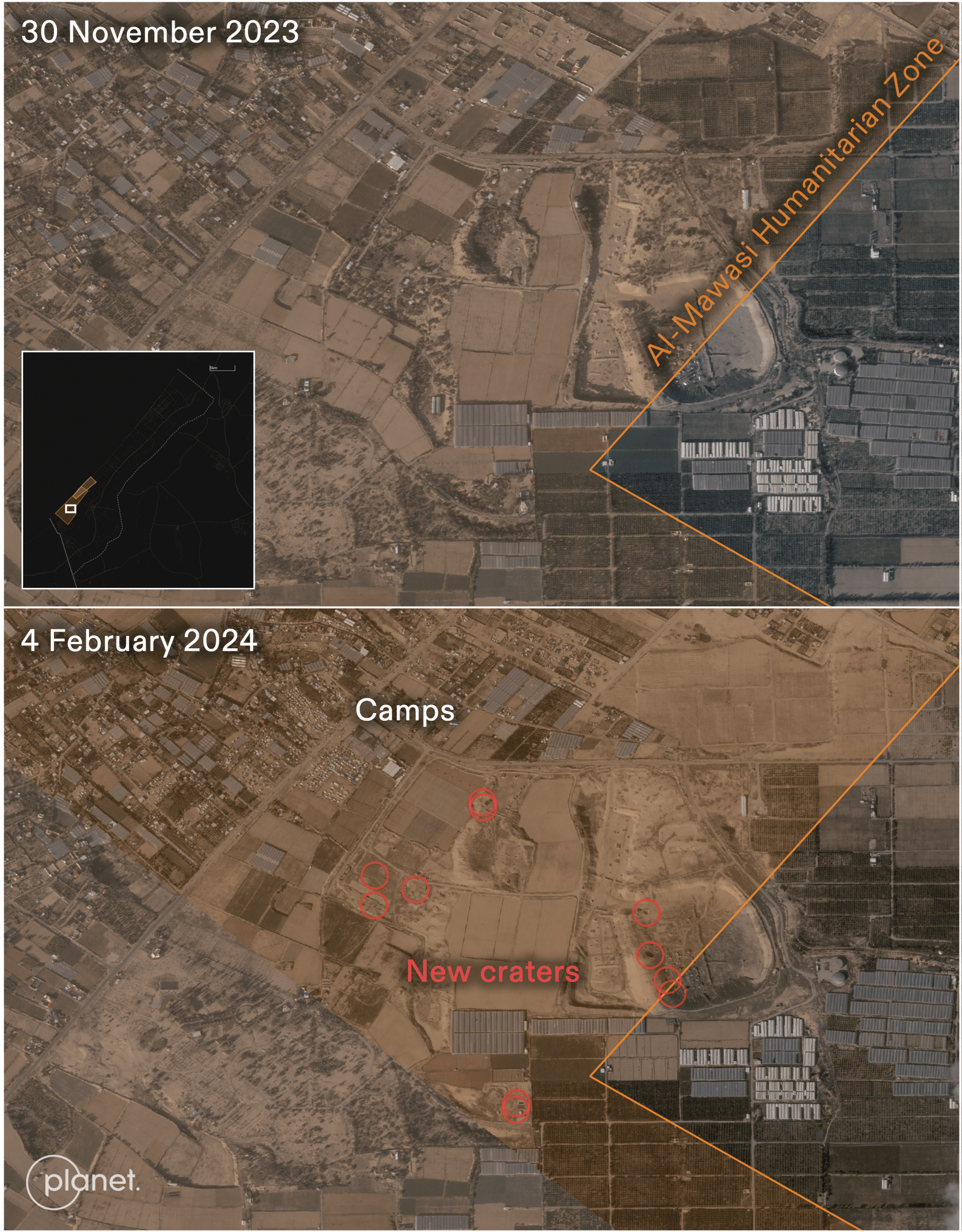

We continued to identify new craters within this declared ‘safe zone’ through 4 February 2024 (see Figure 21).

Destruction analysis published by UNOSAT indicates that the ‘safe zones’ in Rafah and Deir al-Balah were also attacked and damaged, as of 7 January 2024 (see Figure 22-23).

Attacks on Hospitals and Schools serving as ‘shelters’

Attacks on Hospitals

In addition to their function as critical forms of medical infrastructure, hospitals in Gaza have also been key sites of refuge for displaced persons during the ground invasion. The destruction of this infrastructure has created life-threatening conditions that have effectively brought about forced population transfer, leading to the displacement of thousands of individuals seeking shelter. Gaza’s largest hospital, al-Shifa, was reported to have sheltered at least 50,000 displaced persons before it was invaded and depopulated on 15 November 2023. Similarly, the invasion of al-Quds Hospital between 13 and 14 November 2023 caused the additional displacement of 12,000 people who had been sheltering there.

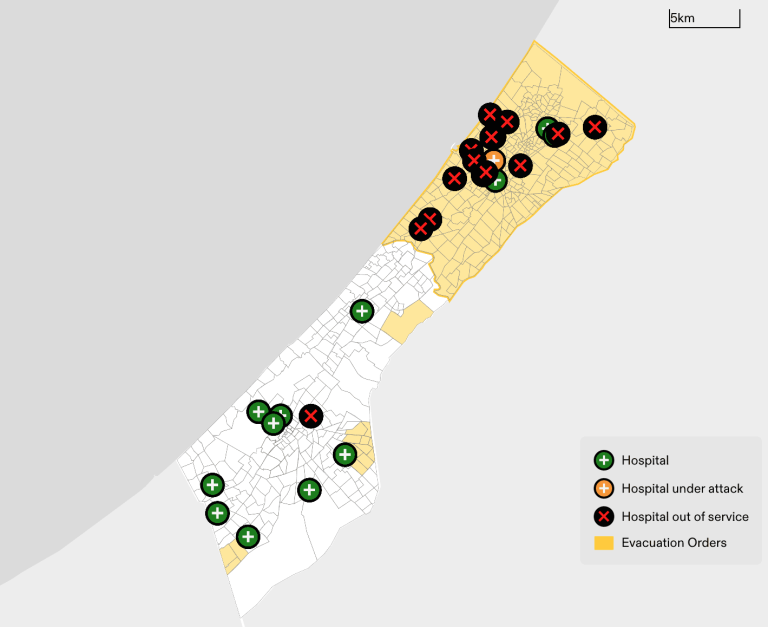

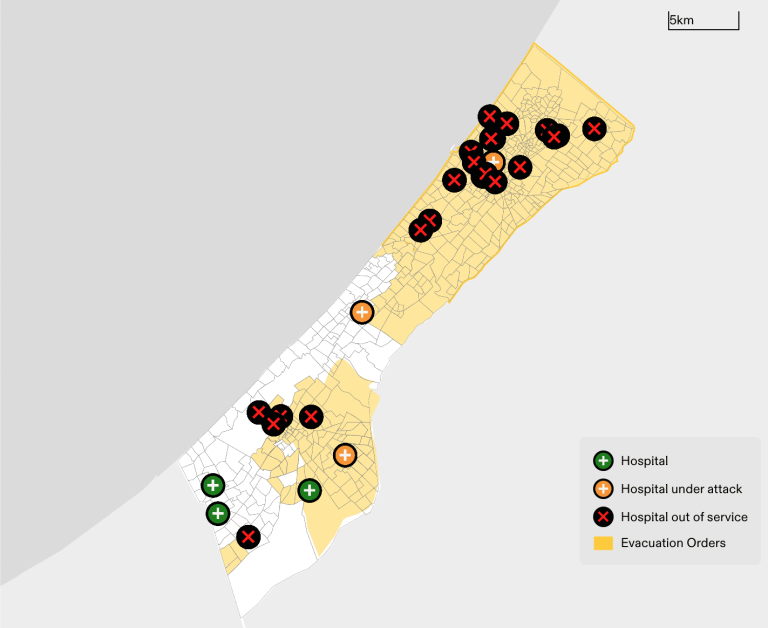

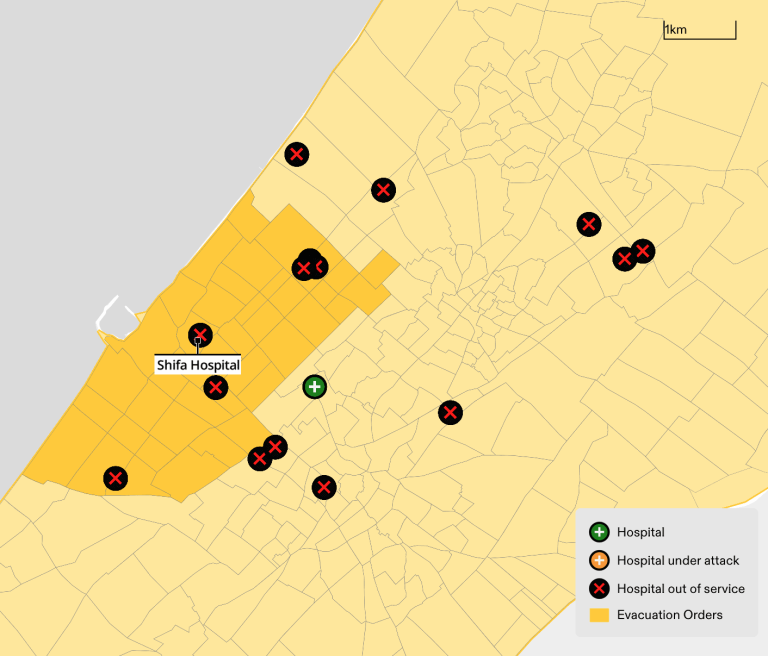

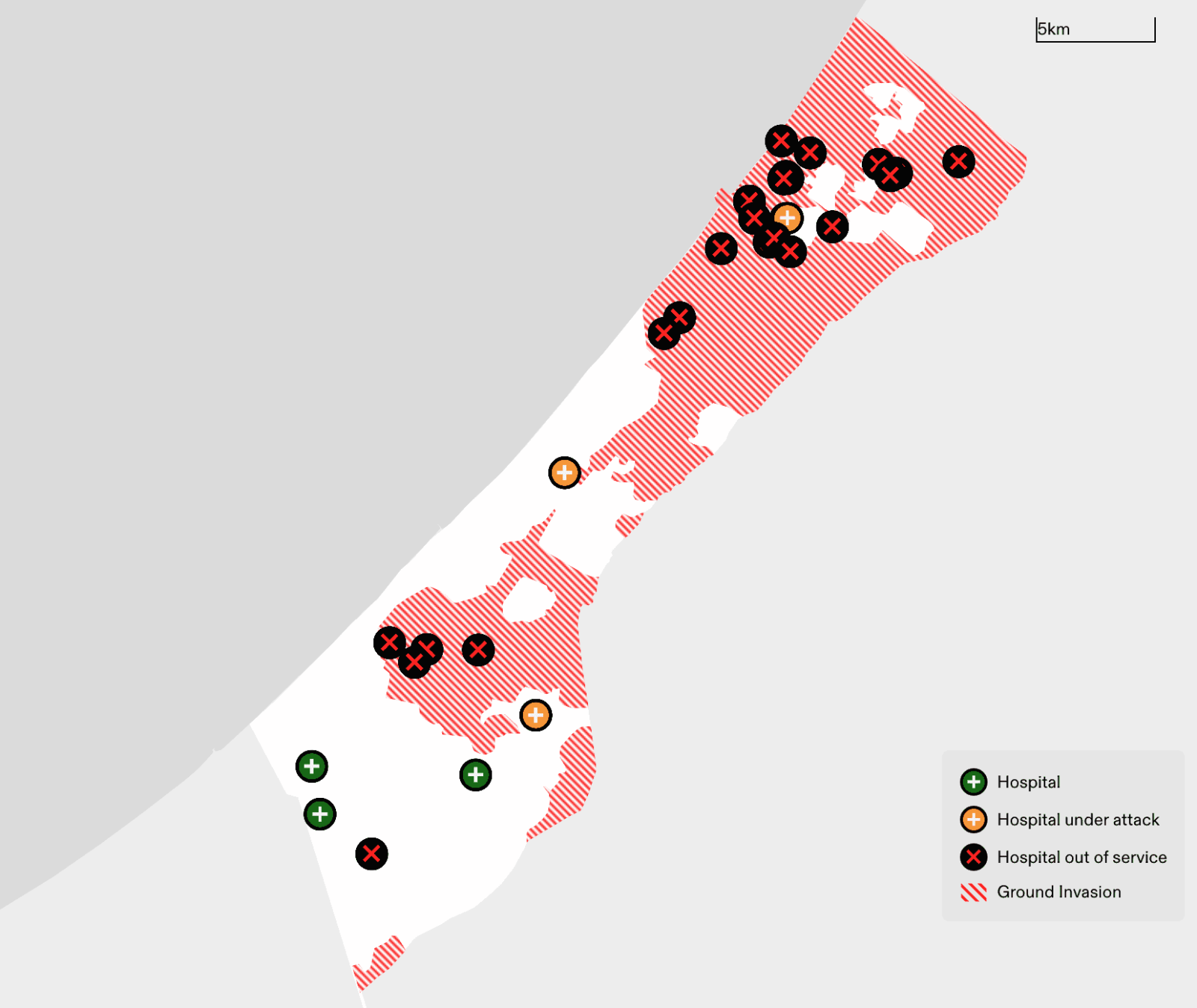

The destruction of medical infrastructure in Gaza has unfolded in tandem with the expansion and spatial distribution of the ‘evacuation orders’ and Israeli ground invasion, progressing from ‘north’ to ‘south’ and mimicking the same pattern of attacks on hospitals that Forensic Architecture has previously documented.

At least twenty-four hospitals have reportedly been forced out of service across the Gaza Strip. These hospitals are primarily located within areas that have received ‘evacuation orders’ (see Figure 25).

All hospitals located in areas reached by the advancing ground invasion were reportedly forced out of service (see Figure 27), including al-Khair Hospital in al-Mawasi, which was not subject to any ‘evacuation orders’. On 22 January, the Israeli army stormed al-Khair Hospital, the only hospital located in the ‘safe zone’ in al-Mawasi, and arrested members of staff, according to the Gaza health ministry (see Figure 28).

Attacks on Schools

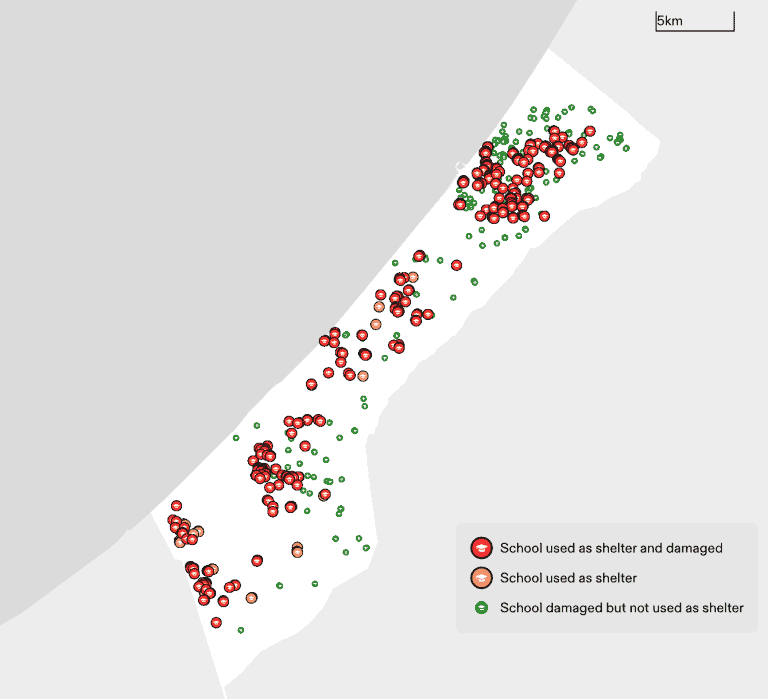

According to data published by the UN on 2 March 2024, 318 schools have served as shelters since October. Based on satellite imagery analysis and initial field reports, at least 287 of these schools have been damaged or destroyed, and 39 of them were located within the supposed ‘safe zone’ of the Rafah municipality. The attacks on and destruction of these facilities has led to further displacement of the civilian population taking refuge in them (see Figure 29).

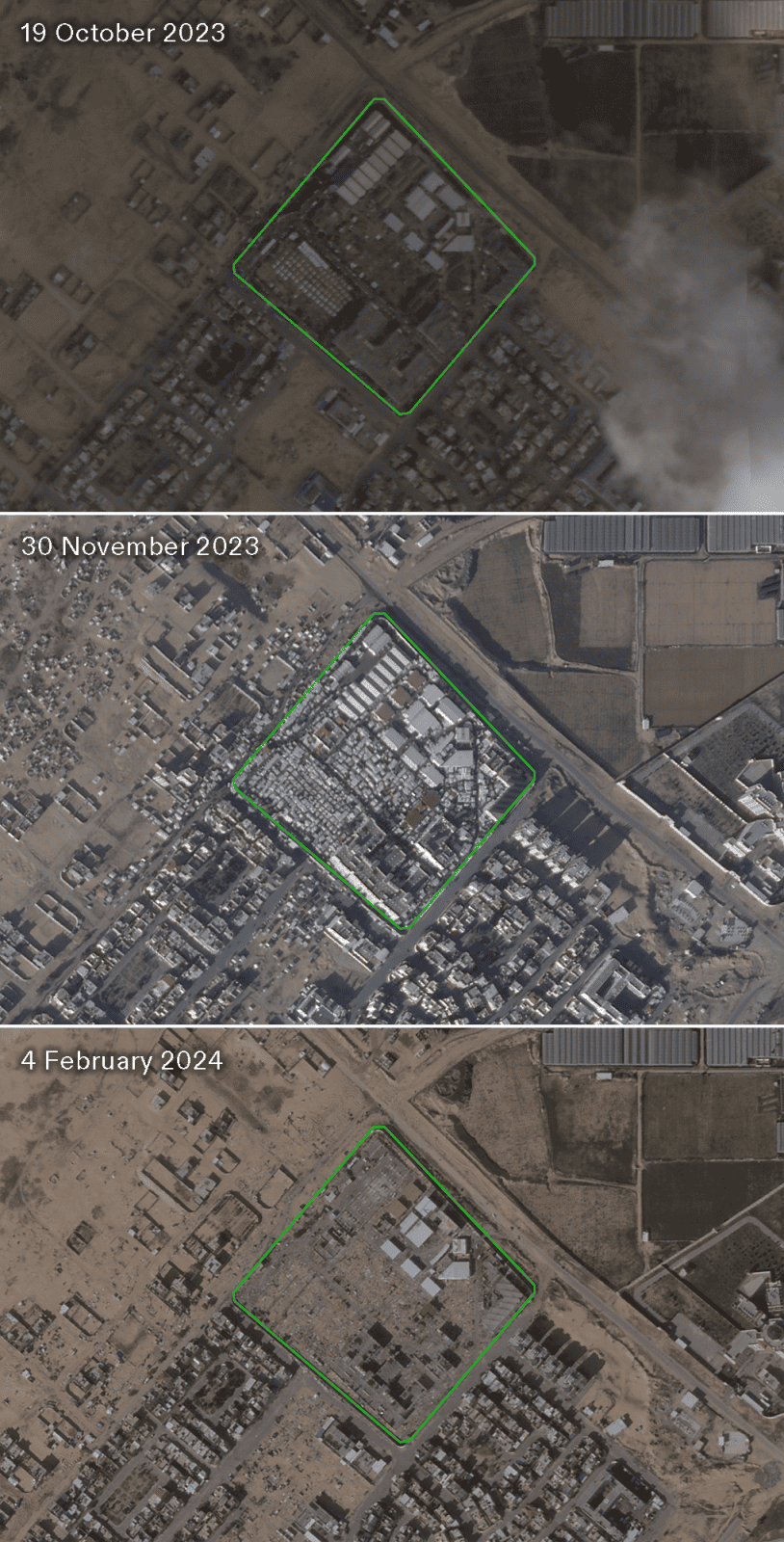

Attacks on educational facilities acting as shelters also include training centres like the UNRWA Khan Younis Training Centre (KYTC), located directly adjacent to the ‘humanitarian area’ in al-Mawasi. The facility became an overcrowded shelter for 43,000 displaced persons. Satellite images taken by Planet on 30 November 2023 show tents dispersed throughout the UNRWA facility. On 24 January, the UN reported that thirteen people were killed and many more injured when a building within the facility was hit by direct fire. Two days later, on 26 January, the Israeli army ordered the displaced civilians taking refuge in the UN-run shelter to leave by the afternoon of the same day. Satellite imagery from 4 February shows the evacuation of the tent camp, which was then cleared and destroyed (see Figure 30).

At the International Court of Justice (ICJ), Israel has cited its use of ‘humanitarian measures’ to defend itself against the charge of genocide. Our research reveals these measures, far from protecting Palestinian civilians, serve rather to support Israel’s genocidal campaign by systematically forcing civilians into unliveable areas, where they inevitably come under renewed attack, only to be displaced yet again. Israel’s abuse of ‘humanitarian measures’ has not only continued but escalated since the ICJ’s 26 January ruling on provisional measures, as the 1.5 million civilians now sheltering in Rafah find themselves at risk of imminent attack with nowhere left to flee to.