Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

On 23 June 2020, Ahmad Erekat, a 26-year-old Palestinian, was shot by Israeli occupation forces after his car crashed into a booth at the ‘Container’ checkpoint between Jerusalem and Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank. Working in collaboration with the Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq, Forensic Architecture’s Palestine Unit was asked by the Erekat family to examine the incident. Using 3D modeling, shadow analysis and open-source investigation, we established the circumstances of the crash of Ahmad’s car, the use of lethal force, the denial of medical aid that followed, and the degrading treatment of Ahmad’s body. Our analysis raises major questions about Ahmad’s killing that raise doubts in the Israeli army’s claims and call for further investigation.

On 23 June 2020, Ahmad Erekat, a 26-year-old Palestinian, was shot by Israeli occupation forces after his car crashed into a booth at the ‘Container’ checkpoint—between Jerusalem and Bethlehem—in the occupied West Bank in Palestine. According to his family, he was driving to run errands for his sister’s wedding taking place on the same day.

Working in collaboration with the Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq, Forensic Architecture’s Palestine Unit was asked by the Erekat family to examine the incident.

We sought to establish:

1. the circumstances of the crash of Ahmad’s car,

2. the use of lethal force,

3. the denial of medical aid that followed, and

4. the degrading treatment of Ahmad’s body.

The available evidence included images and videos taken by bystanders and journalists, a recording of a security camera operated by the Israeli army, and testimonies of bystanders and medical staff.

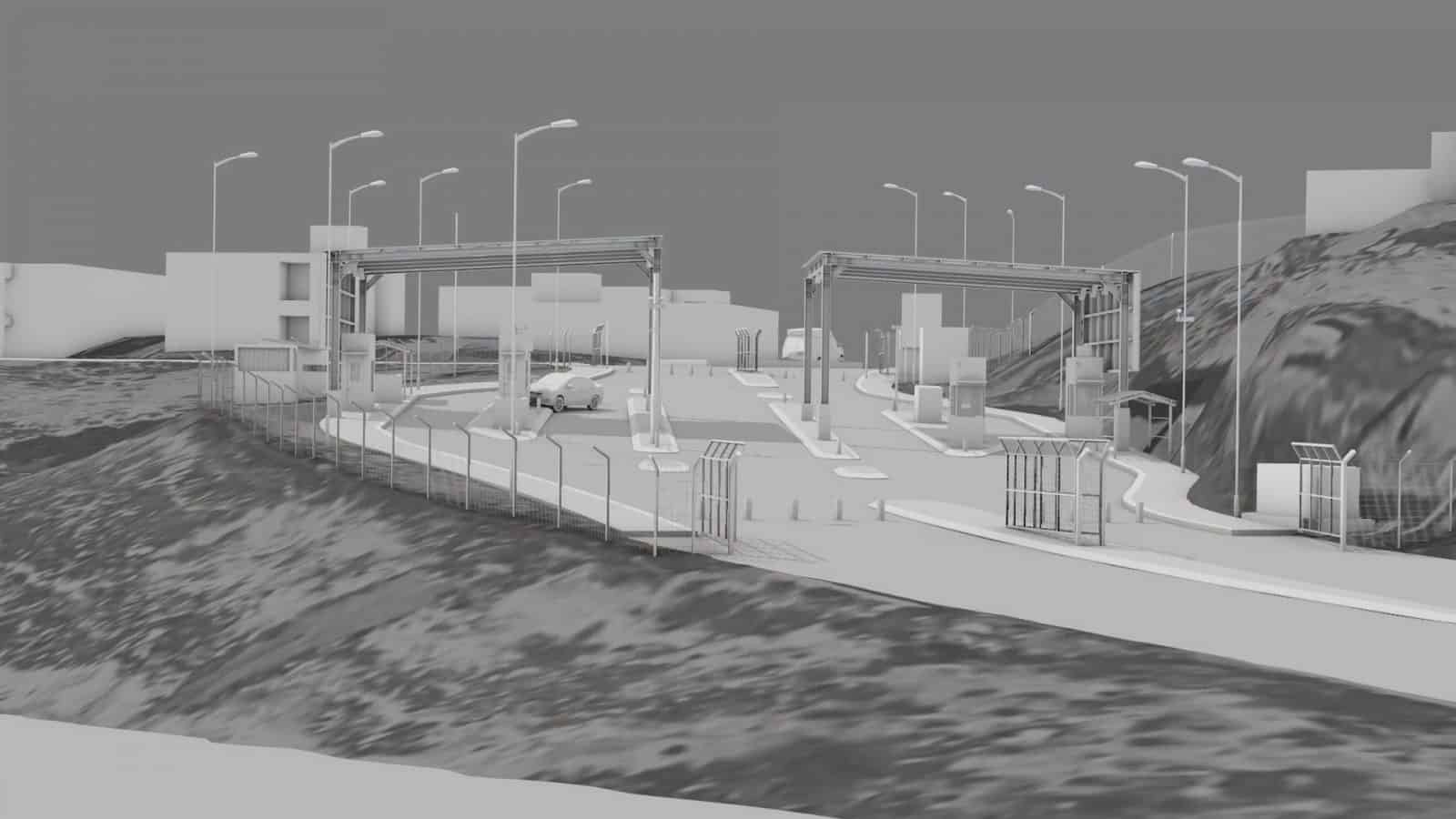

Based on a survey of the checkpoint, we built a detailed 3D model.

Ahmad’s Car: No sudden attempt to speed up

A day after the killing, the Israeli army released a video, recorded on a mobile phone, which showed a screen playing security camera footage of the incident. The footage showed Ahmad’s car veering into a boot and hitting a soldier, who immediately gets up on her feet. Two other soldiers then shoot Ahmad, who raises his arms and falls to the ground.

The military claimed that it was an intentional attack, but produced no evidence that the crash was not the result of an error or a vehicle malfunction.

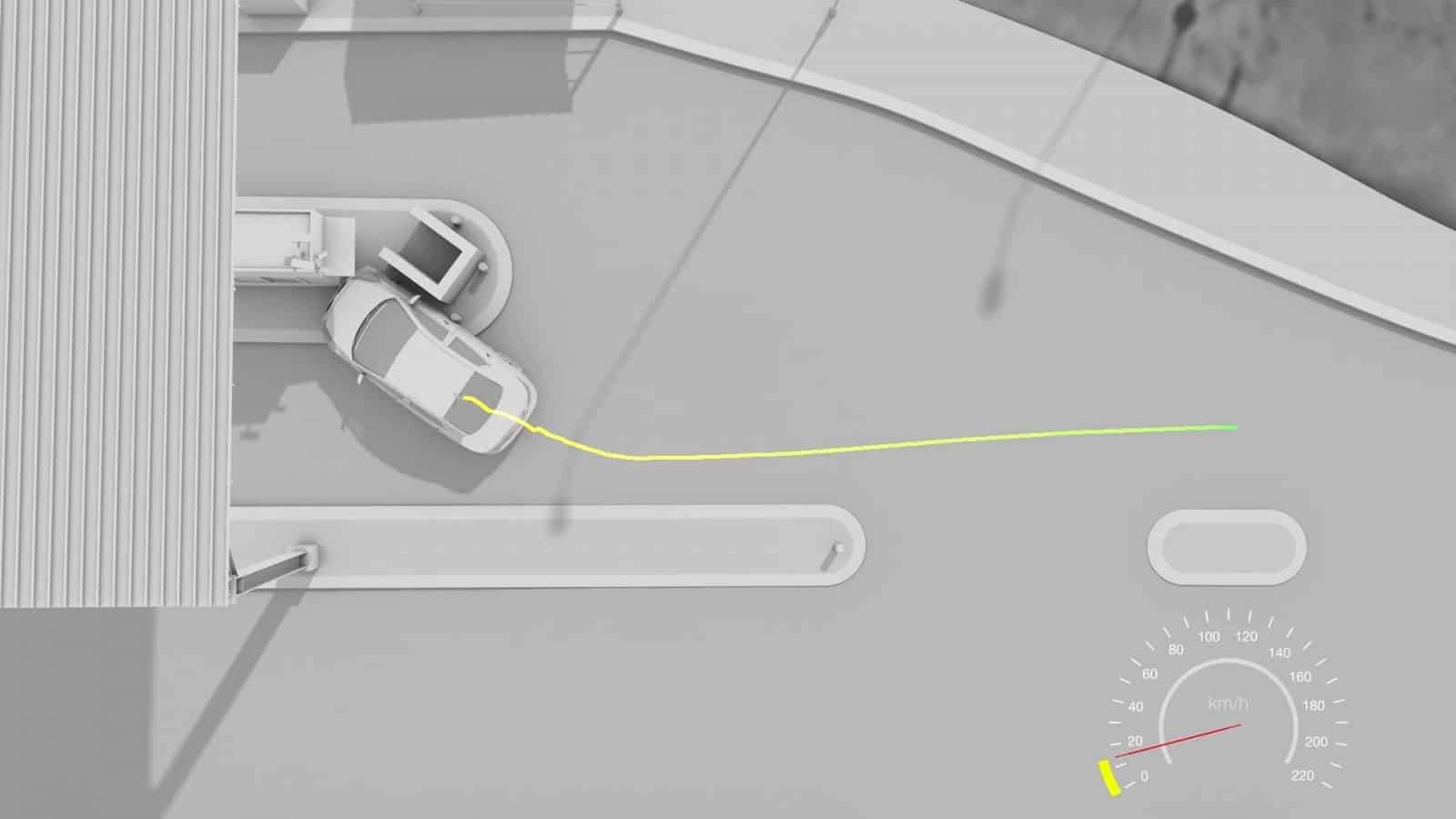

From the perspective of the released footage, the car appears to accelerate into the booth. However, our model allows us to analyse other perspectives that cast doubt on the military’s claims. It also allows us to precisely reconstruct the path of the car, its speed, and its acceleration.

The model shows us that the car veers to the left, and just before impact with the curb, it shifts its course.

The car’s speed did not exceed 15 km/hr—its acceleration was constant and low throughout, implying that there was no sudden attempt to speed up.

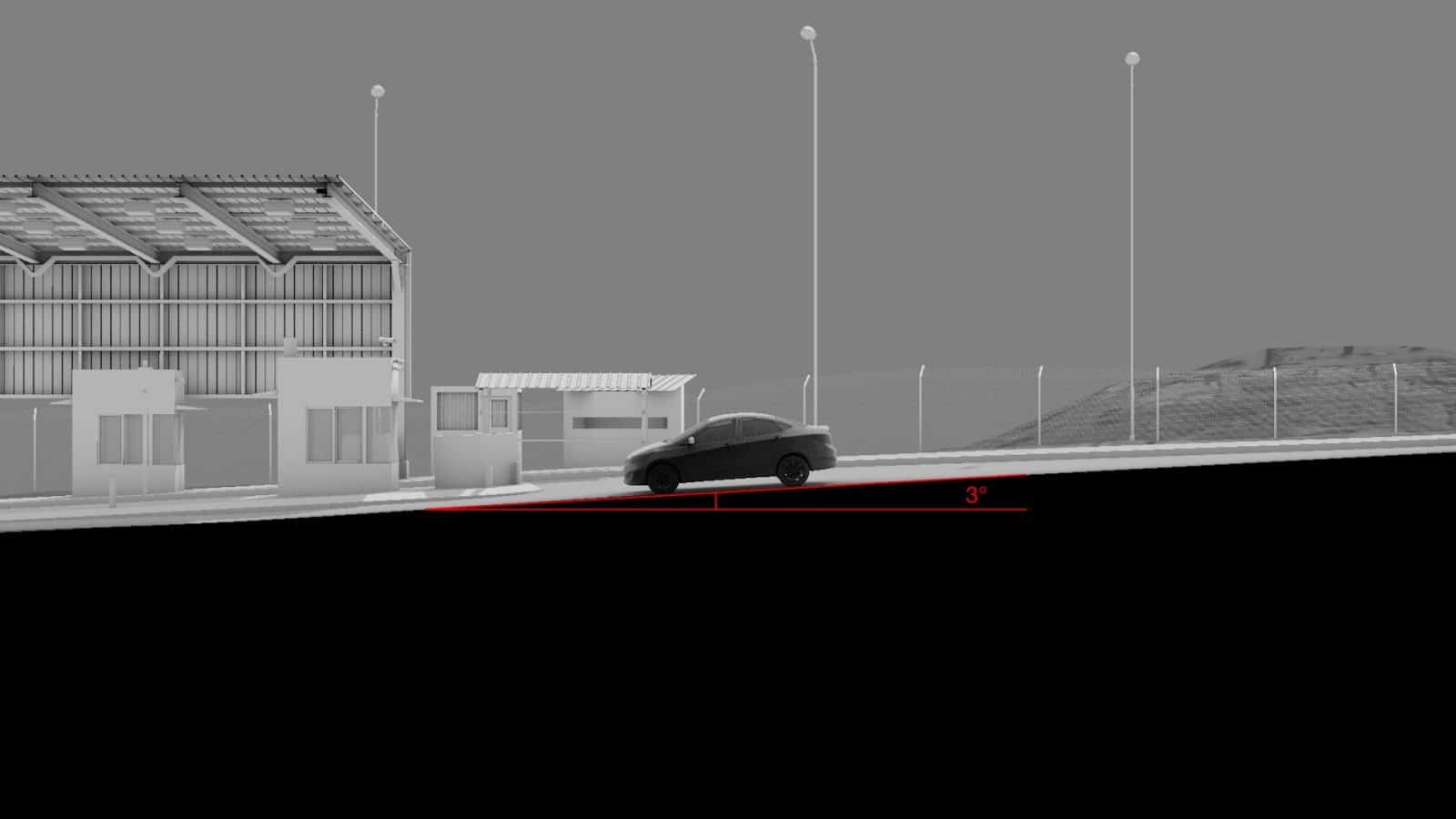

We measured the slope to be 3 degrees—sharp enough to contribute to the speed of the car.

We showed our analysis to forensic collision expert Dr Jeremy J. Bauer. He confirmed that:

‘The acceleration of the vehicle was only 4.4% of its reported capacity after turning towards the booth. Thus, the driver did not rapidly accelerate into the checkpoint. Had the driver truly wanted to maximize the chance that he would surprise the guards and strike them with his vehicle, he could have accelerated to the maximum capacity of the vehicle.’

The video also reveals other details that cast doubt on the army’s narrative. Shortly before impact with the booth, the distance between the back wheel and the body of the car expands which, according to Dr Bauer, possibly indicates that the car was slowing.

Before impact with the soldier, we also noticed that the front left wheel appears still for several moments.

While the quality and frame rate of the video makes this analysis inconclusive, it raises the possibility that shortly before impact, Ahmad was braking.

Together, the car’s constant acceleration at a fraction of its capacity, the low speed of impact despite the sharp slope, the correction of the car’s path after initially veering to the left, and the possibility that Ahmad braked before impact all raise doubts that this was an intentional attack.

However, the Israeli authorities have not opened a formal investigation into the crash, it has not released the rest of the security footage, nor has it examined the car’s black box, which could help answer these questions.

Israeli Army’s Use of Lethal Force

An Israeli border police officer claimed that Ahmad ‘left the car and began running towards the soldiers.’

With this claim of self-defence, the Israeli authorities—whose officers were armed and in protective gear—sought to justify its extrajudicial execution of Ahmad.

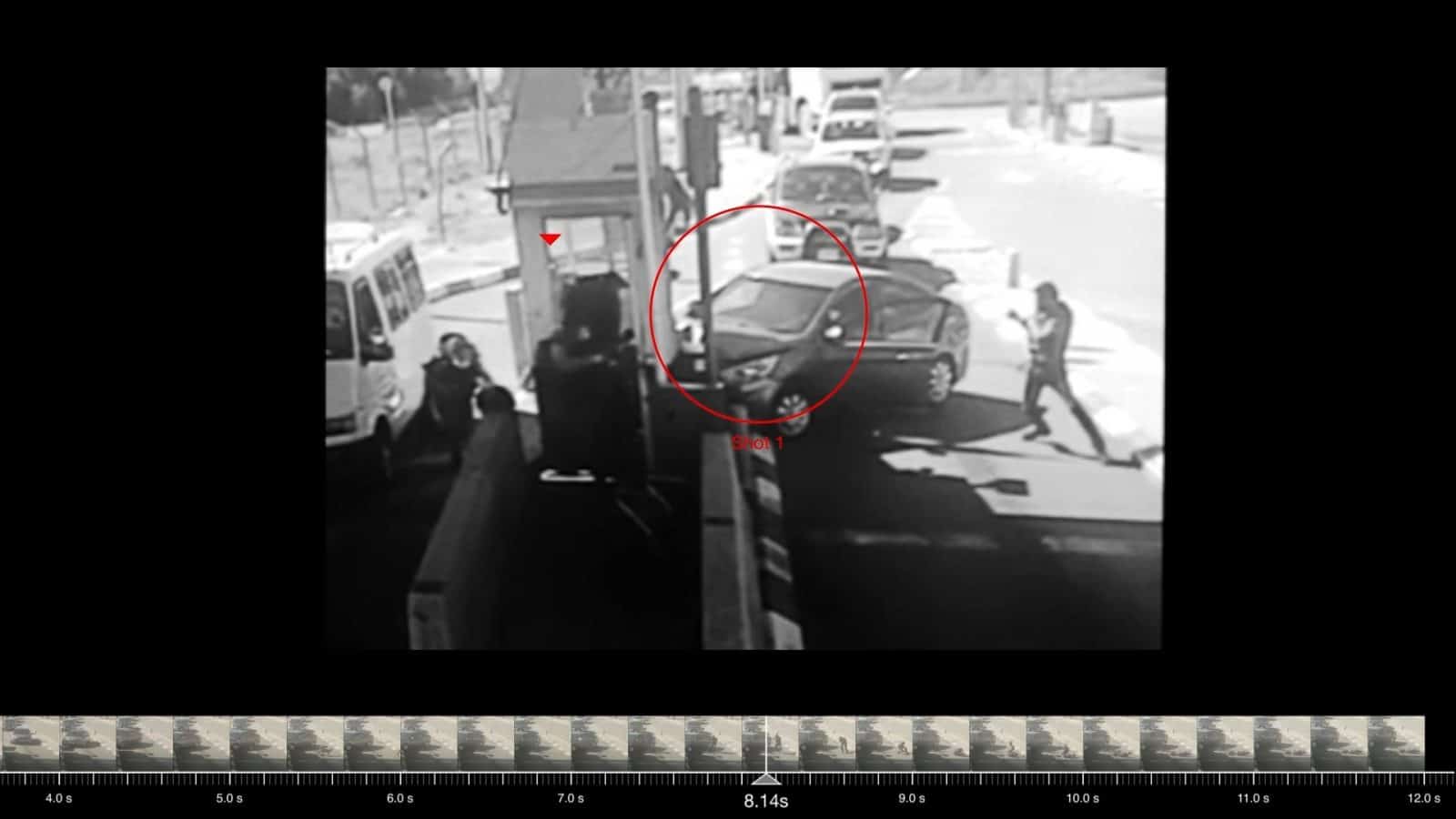

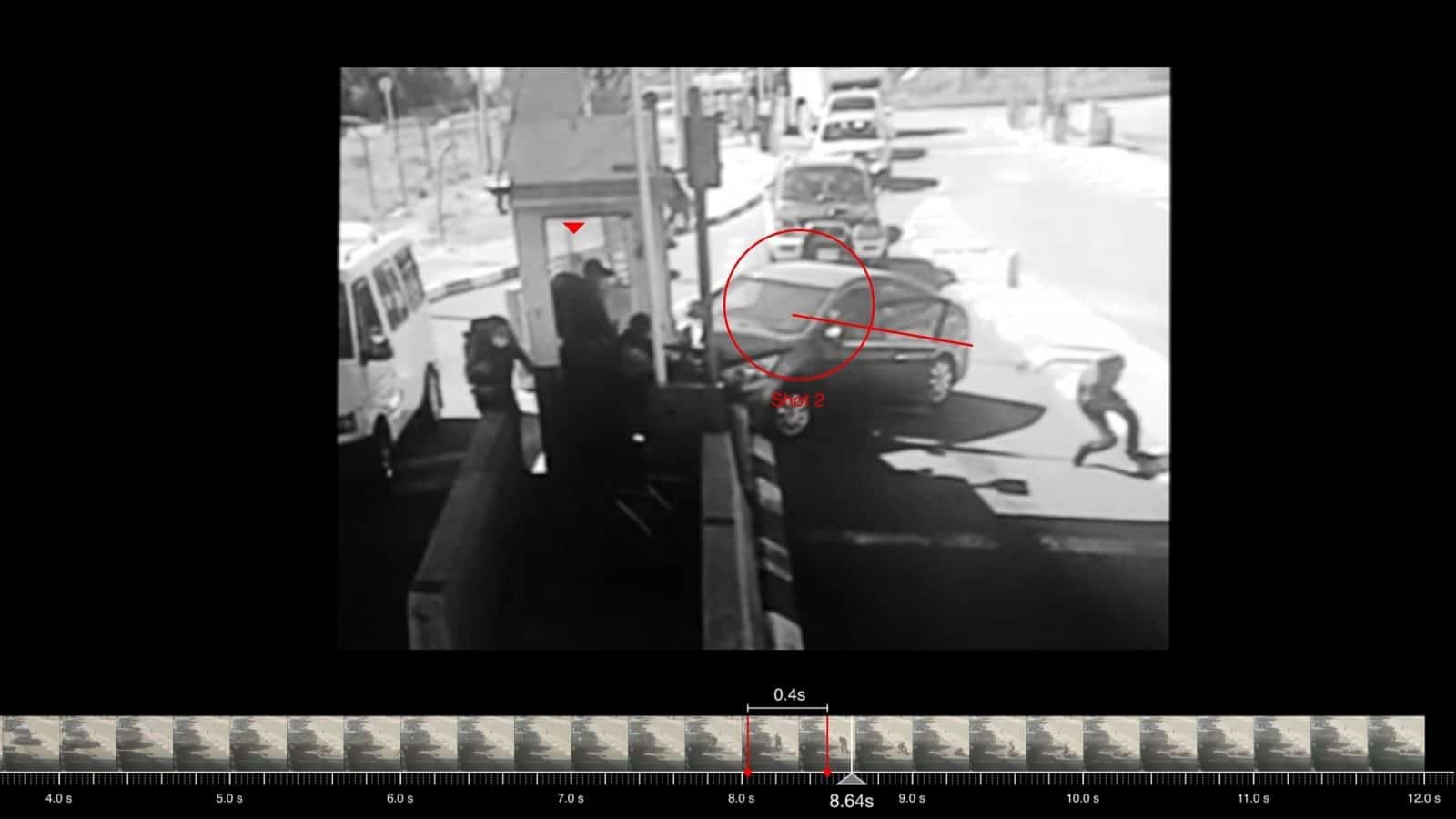

We conducted a frame-by-frame analysis of the security camera footage, stabilising the camera and increasing the contrast of the footage to enhance its clarity and examine Ahmad’s movements and positions.

After the impact, Ahmad leaves the vehicle unarmed and moves away from the soldiers, raising his hands in the air.

Ahmad is first shot when standing around 4 meters away from the nearest soldier. He then continues to move backwards as he falls to the ground.

According to the Israeli army’s open-fire regulations, live fire may only be used in a last resort if there is ‘life-threatening danger.’ Our analysis contradicts the army’s claim, showing that Ahmad did not pose any immediate threat.

6 Shots

Smoke from each shot becomes visible when we make the footage black and white.

The first shot is fired one second after Ahmad exits the car, by a soldier standing behind the booth. The bullet appears to hit Ahmad in the abdomen or chest area.

The second shot is fired 0.4 seconds later by the same soldier when Ahmad is in this position.

The third shot is fired 0.3 seconds later. Its smoke appears here and aligns with the rifle of the soldier in the front.

The same applies to the fourth, fifth, and sixth shots that followed—in fast succession.

All in all, It took Israeli soldiers 2 seconds to fire 6 shots at Ahmad. We examined the position of Ahmad’s body when each shot was fired.

When the first two shots are fired, Ahmad is raising his arms and moving backwards, and the third shot is fired as he is falling. The last 3 shots were fired when Ahmad was already on the ground.

Denial of Medical Attention

An Israeli military spokesperson stated that Ahmad was provided with medical care ‘within minutes‘ but the army has not released evidence of this despite having over a dozen security cameras at the checkpoint.

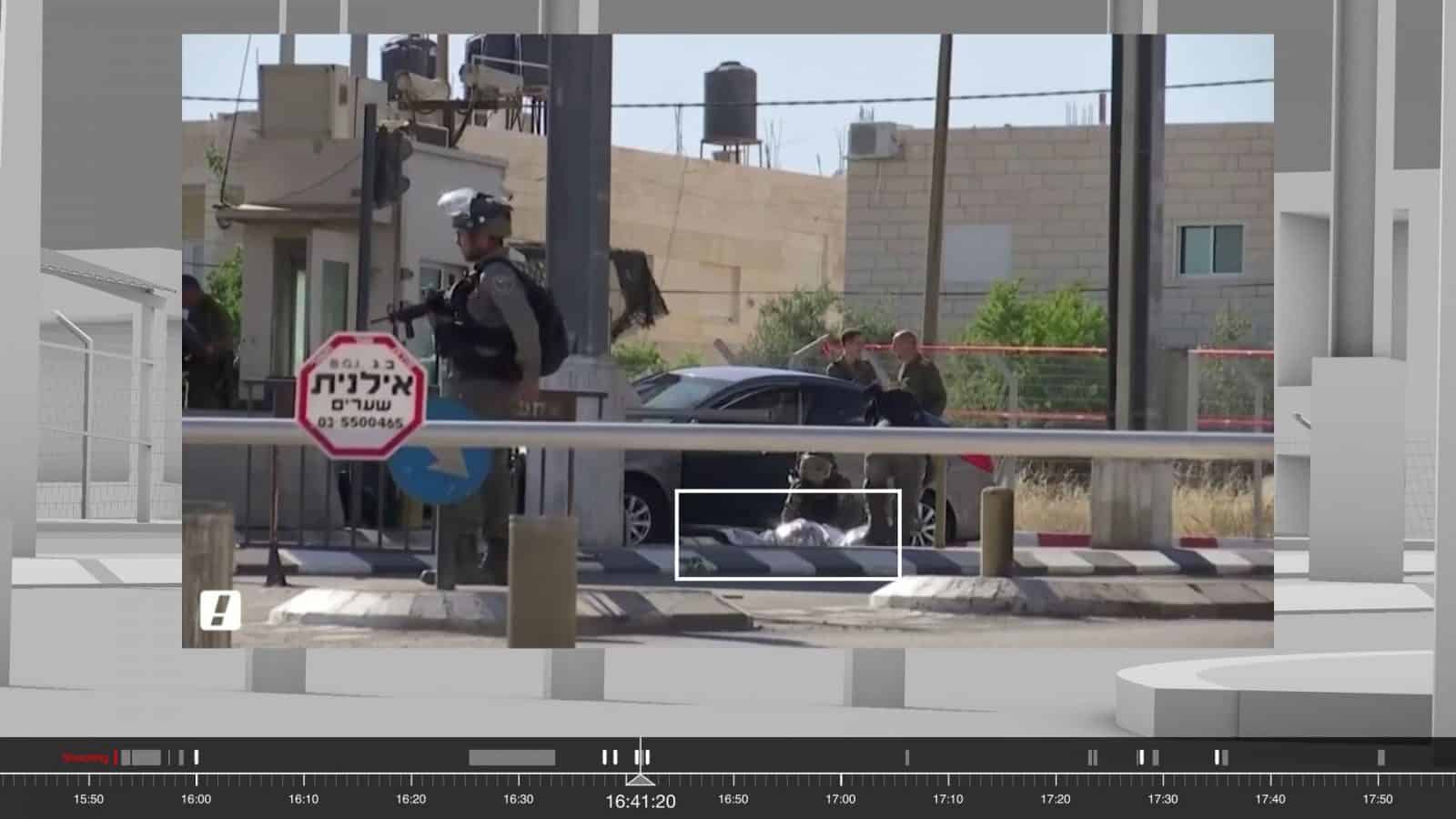

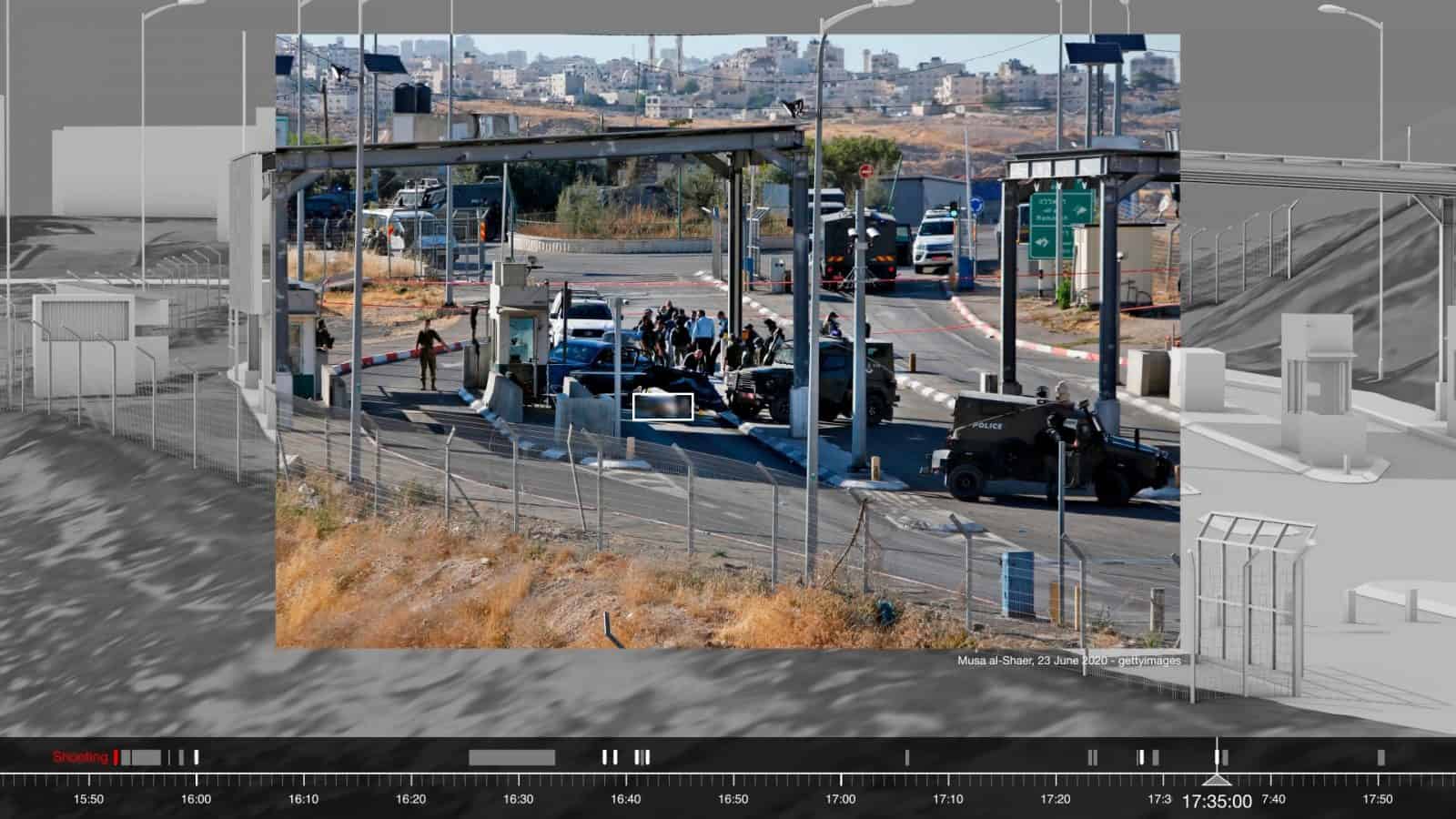

We collected dozens of online photographs and videos taken in the next few hours after the shooting, and synchronised and geolocated this footage using our 3D model.

Although most of the footage did not have a time stamp, we were able to compose a timeline within a 5-minute margin of events that followed Ahmad’s shooting using shadow-analysis.

Footage taken at 3:53 p.m. by a witness—moments after we believe Ahmad was shot—shows him moving, presumably alive.

An Israeli ambulance arrives approximately between 3:57 p.m. and 4:03 p.m— four to ten minutes after the shooting. By 4:15 p.m., around 20 minutes after the shooting, a Palestinian ambulance arrived but was denied access by the Israeli army:

‘A soldier at the outer gate told us to stop. We stayed there for about 10 minutes. Soldiers then told us to get out of the area, and that the military jeeps behind us needed to pass. From our far viewpoint, and from conversations with witnesses and the team, we understood that no kind of medical care was provided to him.’

(Anonymous testimony by Palestinian ambulance driver to Al-Haq, August 2020)

The Israeli ambulance remained at the checkpoint for about 30 minutes, until approximately 4:30 p.m. when it left—taking with it only the wounded Israeli soldier.

Placing photographs taken 8 minutes after the Israeli ambulance left within our 3D model, shows that Ahmad’s body is still in the same position we saw him in when he was seen alive 45 minutes prior.

Ahmad’s body would have moved if he had received medical attention. It is therefore extremely unlikely that Ahmad was provided medical care—care that could have saved his life in those moments.

The practice of denying medical care is an act of ‘killing by time’.

Degrading Treatment of Ahmad’s Body

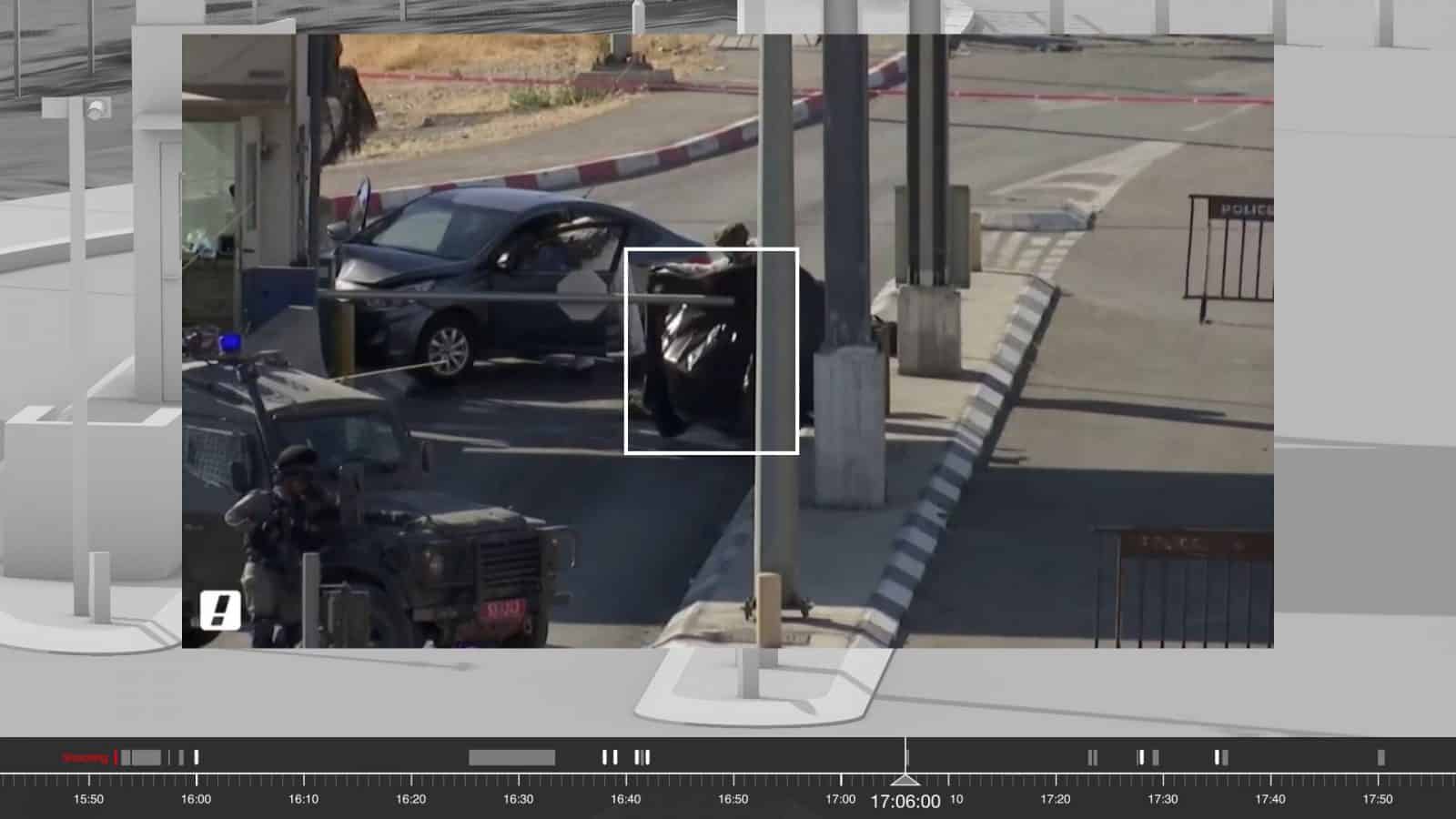

Ahmad’s body was left uncovered by the Israeli occupation forces for 10-minutes after the Israeli ambulance left the scene.

At 4:41 p.m., roughly 45 minutes after the shooting, we first see Ahmad’s body being covered with a silver tarp.

Around twenty-five minutes later, Ahmad’s body is covered with another black sheet by the Israeli bomb disposal unit.

At 5:23 p.m., other personnel place markers and take photos of his body, and around five minutes later, the black cover is removed, and we see Ahmad’s body with his shirt taken off.

By around 5:30 p.m.—over an hour and a half after the shooting—Ahmad appears to lay completely naked on the ground, surrounded by around 20 Israeli police and military personnel, including 2 military jeeps and police vehicles.

We have not come across another case where a slain Palestinian was fully undressed on-site by the Israeli army.

Finally, by around 5:50 p.m., Ahmad is taken by an Israeli ambulance.

Collective Punishment of Palestinian Families

Continuing their degrading treatment, the occupation forces have confiscated Ahmad’s body—refusing to return him to his family for proper burial.

The Israeli authorities have also not released an autopsy detailing Ahmad’s wounds and time of death.

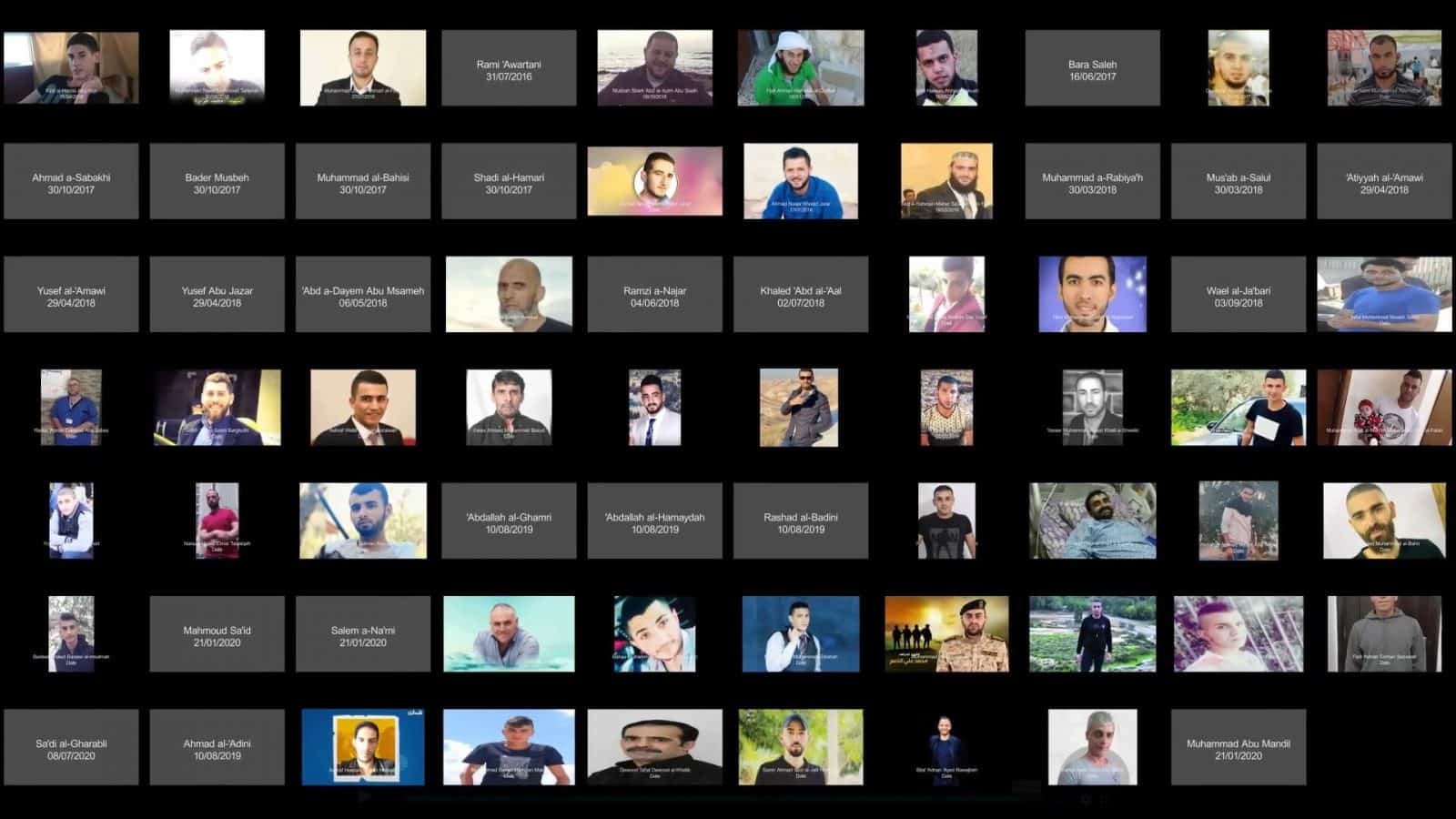

Ahmad is not alone. He is one of 70 Palestinians whose bodies have been confiscated from their families—a practice of collective punishment.

Placing this killing alongside other extrajudicial executions by the Israeli occupation forces, another pattern appears whereby Palestinians are denied medical attention after being shot with lethal force.

Moreover, Ahmad’s extrajudicial execution took place at a time of global Black-led protests against racist police brutality.

In this context, his killing illustrates both the entangled struggles of Palestinian and Black liberation, as well as the disposability of Black and indigenous bodies in hyper-militarized settler-colonies.