Methodologies

Location

Publication Date

This comprehensive written report supports our investigation into our joint investigation with Al-Haq’s FAI Unit into the killing of journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, detailing the methodologies we employed and including a step-by-step breakdown of the visual, audio and spatial analysis we undertook to come to each of our investigation’s conclusions.

Contents

- Background

- Summary

- Defining the ‘incident’

-

Material Used in Analysis

- Material received from Al Jazeera

- Material received from witnesses

- Additional materials used

- Commissioned photo/video survey

- Documents

-

Methodology

- Footage

- Site documentation

-

Video analysis

- Synchronization

- Footage speed and analysis

- Zoom

- Audio analysis

-

3D reconstruction

- Photogrammetry

- Shadow analysis

- Geolocation

- Optics simulation

- Testimony

- Timeline of Incident

- Analysis

- Summary of Findings

- About Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq

- Case File Examples of Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq

1. Background

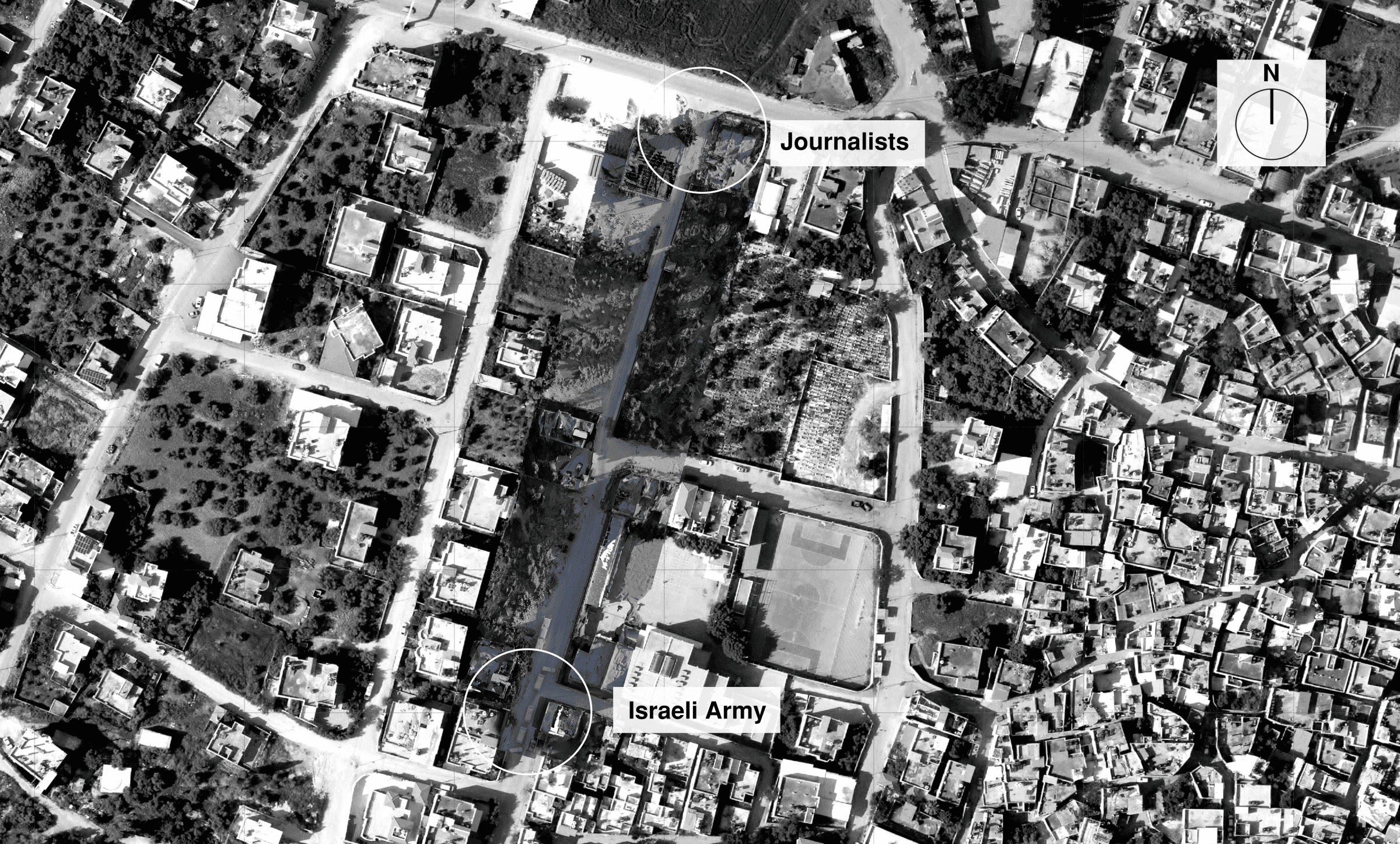

On 11 May 2022, Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh and a group of five other journalists arrived at Balat Al Shuhada’ street in Jenin to report on a raid on the nearby refugee camp by the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). The journalists wore prominent ‘PRESS’ vests that identified them as such, from both the front and back, and followed standard protocols for self-identification as they slowly approached a convoy of five armoured Israeli military vehicles parked along an unnamed street intersecting Balat Al Shuhada’. The Israeli army vehicles were approximately 200 metres south of the journalists.

2. Summary

At 6:31 AM, an Israeli army special forces marksman1 fired the first burst of six bullets directly at the group of journalists from a sniper hole in the military vehicle at the front of the Israeli army convoy. One of the shots hit journalist Ali Al-Samoudi in the shoulder. Eight seconds later, as the journalists attempted to take cover, the Israeli army marksman fired a second burst consisting of a further seven distinct gunshots, once again targeting the journalists. One of those bullets hit Shireen Abu Akleh in the head, fatally wounding her. Two minutes later, an unarmed civilian, Sharif al-Azab, attempted to deliver first aid to Shireen, and he, too, was fired at with three distinct gunshots.

Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq’s investigation offers detailed forensic evidence regarding the circumstances of Shireen Abu Akleh’s killing on 11 May 2022.

Our investigation conclusively demonstrates that:

- The journalists were clearly identifiable as press/non-combatants to the Israeli army marksman.

- The Israeli army marksman deliberately and repeatedly targeted Shireen and her fellow journalists with the intention to kill.

- The attack on Shireen and her journalist colleagues occurred during a period without risk to the Israeli army marksman’s life or that of other soldiers. There were no shots other than those of the Israeli marksman fired at the time and no armed individuals in the vicinity of the journalists.

- Shireen was deliberately denied first aid after being shot by the Israeli army.

Our investigation is the first to employ a precise digital reconstruction of the incident. Using advanced spatial and audio analysis, we tracked the location and movements of the various key actors throughout the unfolding incident, including the journalists, civilians, and military vehicles. This reconstruction also allowed us to analyse what the marksman could have seen and the precise trajectories of the shots they fired at the journalists.

We analysed a video recorded by an Al Jazeera cameraperson at the scene, which was provided to us exclusively; we directly obtained other videos taken by witnesses to the incident and gathered other available open-source videos of the events. Additionally, we conducted on-site interviews with survivors and witnesses, we examined the pathological report prepared after Shireen’s death, and we examined material traces left on site. Altogether we examined, synchronised and geolocated over thirty videos, photographs, testimonies, and material finds.

See section 4 for a detailed list of material used in the analysis.

3. Defining the ‘incident’

The incident is composed on three distinct rounds of shootings: 16 shots in total, separated by two breaks. The first round is of 6 shots, the second round is of 7 shots, and the third round is of 3 shots.

We define the ‘incident’ as starting with the first shot of the first round at 6:31:06 and ending 2 minutes 38 seconds later when the last shot of the third round of shooting is fired at 6:33:44. All times referred to in this report are in local Jenin time (UTC +3) and in 24-hour format.

See section 6 for a detailed timeline

4. Material Used in Analysis

-

Material received from Al Jazeera

- Al Jazeera footage

- Bullet image

-

Material received from witnesses

- 16 min full video

- Balcony video 02

-

Additional materials used

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 1

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 2

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 3

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 4

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 5

- Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 6

- Jenin_Camp_Shireen_Satellite

- Tel_hill photo

- Balcony video 01

-

Material by authors

- ALI_shot position

- SH_shot position-2

- IMG_0261

- IMG_0262

- IMG_0263

- IMG_0264

- Tree markings

-

Commissioned video and photographic survey

- Drone footage of site

- Ground photography

-

Documents

- David_Letter_web_210616

-

Government documents

- Autopsy report and affidavit

- Forensic Lab report and affidavit

- Records of evidence

- Witness testimonies

5. Methodology

- Footage

- Site Documentation

-

Open-source intelligence

Open-source intelligence (OSINT) is information collected from publicly available sources. Common OSINT sources include social networks, online forums, corporate and governmental websites, blogs, videos, news reports, and publicly available satellite images.

While open-source information is available to anyone, it is not always straightforward or easy to find, and open-source investigators are required to use a wide variety of open source and proprietary research tools. We used OSINT throughout this investigation, and specifically in order to ascertain information pertaining to the below areas.- Bullet

- Rifle and scope

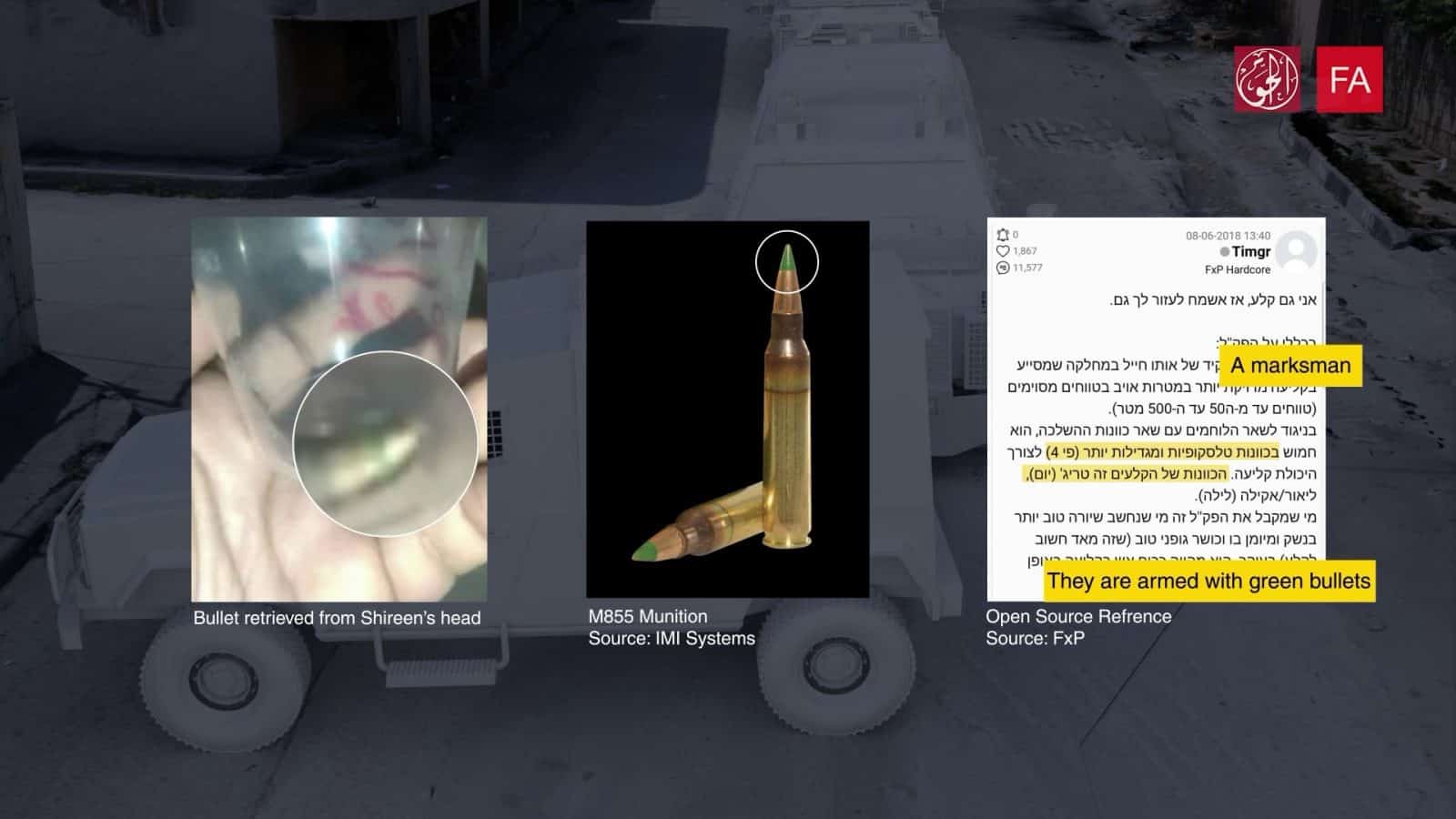

We were provided with Shireen’s autopsy report for the purposes of this investigation. Using the findings in the report, an image of the bullet retrieved from Shireen’s skull ‘bullet image’ (4.1.2) published by Al Jazeera, as well as expert accounts identifying the bullet, we confirmed the bullet as being a 5.56mm bullet with a green tip.2

Through open sources, we identified green-tipped bullets as being M855/SS109 bullets manufactured by IMI (Israel Military Industries). These bullets have shallower ballistic trajectories and higher precision than typical 5.56mm bullets. According to IDF soldiers’ forums, such green tipped 5.56mm ammunition is the standard ammunition for Israeli army marksmen.3

M855/SS109 are longer, and the cartridge has more fire-powder, than a regular bullet. M855 bullets are meant to be fired from a specially-adapted rifle (such as the M4A1 – an M4 rifle adapted for marksmen) equipped with a thicker barrel. The thicker barrel is threaded more densely (7 threads per inch vs 6 threads per inch in a regular M4) to allow the bullet to spin faster as it leaves the barrel. A barrel with more threads makes a bullet spin faster around its axis, thus generating a shallower ballistic trajectory. All of this ensures that the shot is more precise. The thickened barrel is meant to absorb the heat emanating from the increased friction due to the denser threading. These bullets are also reinforced with an internal steel structure.4 As a result of these factors, M855 bullets have higher penetrability through body armour and helmets than regular bullets.Open-source research in equipment lists of the Duvdevan paratrooper special unit, the unit reportedly present in Jenin on that day, revealed that marksmen in such units use M4 rifles.5 We further research online soldiers’ fora, these confirmed that IDF marksmen use the M4 Carbine and further revealed their M4 carbine’s are commonly equipped with an optical scope in the Trijicon ACOG series with a 4x magnification, likely the 4×32 model (the most common model).6

The Trijicon ACOG 4x32mm battle scope, which likely has the same specifications as the scope equipped by the Israeli army marksman, magnifies a scene 4x through a 32mm lens, with a specified field of view of 12.27 meters across the lens at 100 meters away. The scope is designed to be used with one or both eyes open. The specified field of view is perceivable when the lens is 1.5 inches away from the eye (the eye relief specified by the product). The scope is still usable when further away from the eye: this preserves the 4x magnification preserved but the field of view is reduced. A 35mm camera with a 200mm lens replicates 4x magnification given that a 35mm format camera at 50mm focal length correlates to 1x magnification.7 -

Video analysis

- Synchronization

- Footage speed and analysis

- Zoom

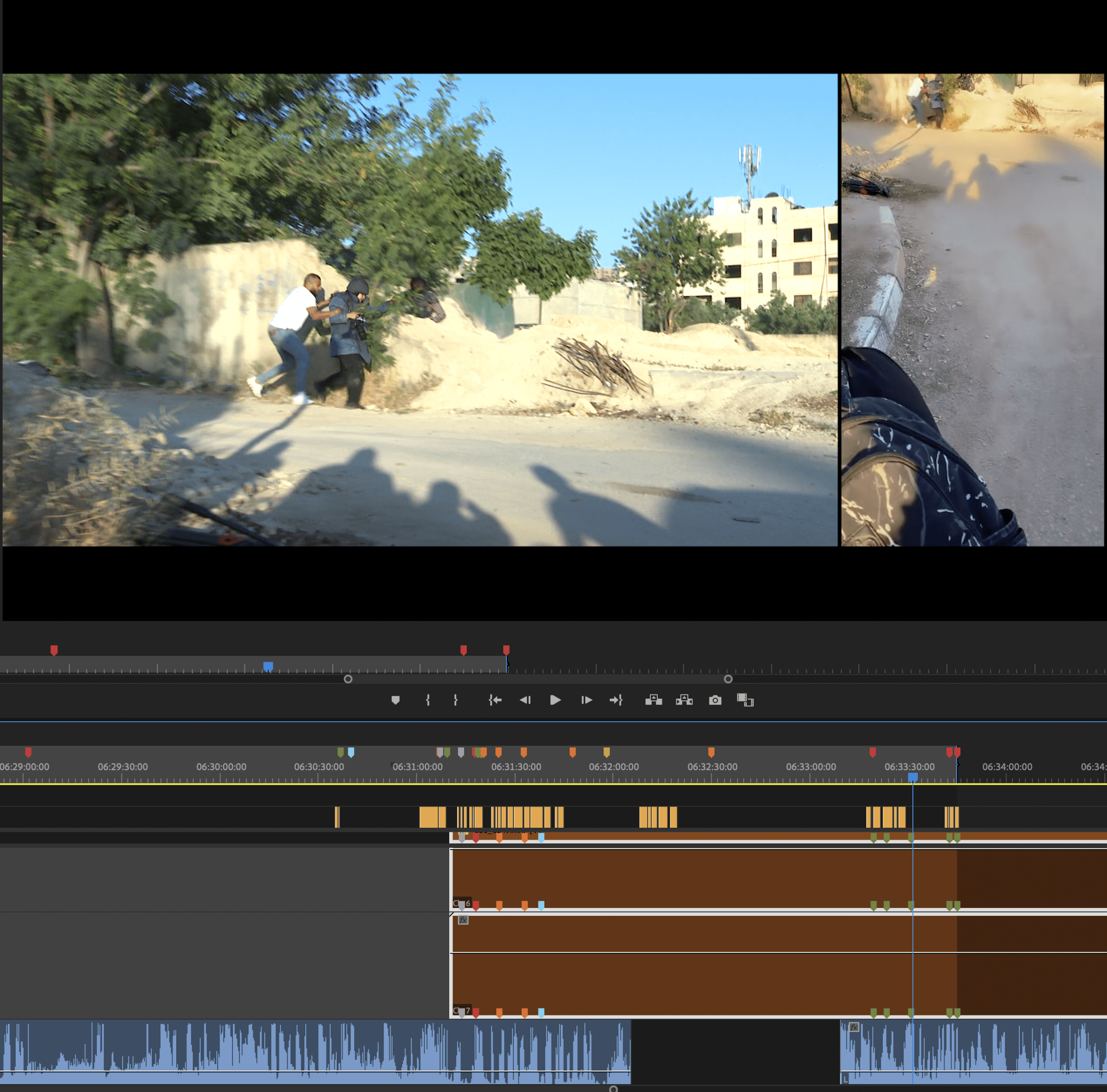

‘Synchronising’ multiple videos describes a process which temporally aligns them within a single video file thus demonstrating when events depicted in one video chronologically overlap with those depicted in other videos. We synchronised ‘Al Jazeera’ and ’16 min video’ using Adobe Premiere Pro, a video editing software, in order to accurately analyse the incident.

![Footage Synchronization - Synchronization of `Al Jazeera` footage (left) and ’16 min video’ taken by Salim Awad (right) using Adobe Premiere Pro. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() Synchronization of `Al Jazeera` footage (left) and ’16 min video’ taken by Salim Awad (right) using Adobe Premiere Pro. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

Synchronization of `Al Jazeera` footage (left) and ’16 min video’ taken by Salim Awad (right) using Adobe Premiere Pro. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)Since we know that ‘16 min video’ was a livestream, we can accurately establish that it began at 6:24 AM. This allowed us to anchor the synchronisation to the real time in Jenin, accurate to the minute. this allowed us to anchor the synchronization to the real time accurate to the minute. ’16 min video’ runs continuously between 6:24:00 until 6:32:05 and again between 6:33:09-6:34:58. ‘Al Jazeera’ begins after the first round of shooting and is continuous between 6:31:10 and 6:34:51. ‘Al Jazeera’ and ’16 min video’ overlap between 6:31:10 – 6:32:05 and between 6:33:09 – 6:34:51.

We examined the videos in ‘slow motion’ to closely studied each frame to break down the actions of all people present in detail. Using Adobe Premiere Pro, we analysed the way in which the incident unfolded frame-by-frame in both ‘Al Jazeera’ and ’16 min video.’

To analyse the incident closely, we used Adobe Premiere Pro to zoom in on the subjects such that they occupied most of the screen, which allowed us to isolate and better see the elements captured in the footage.

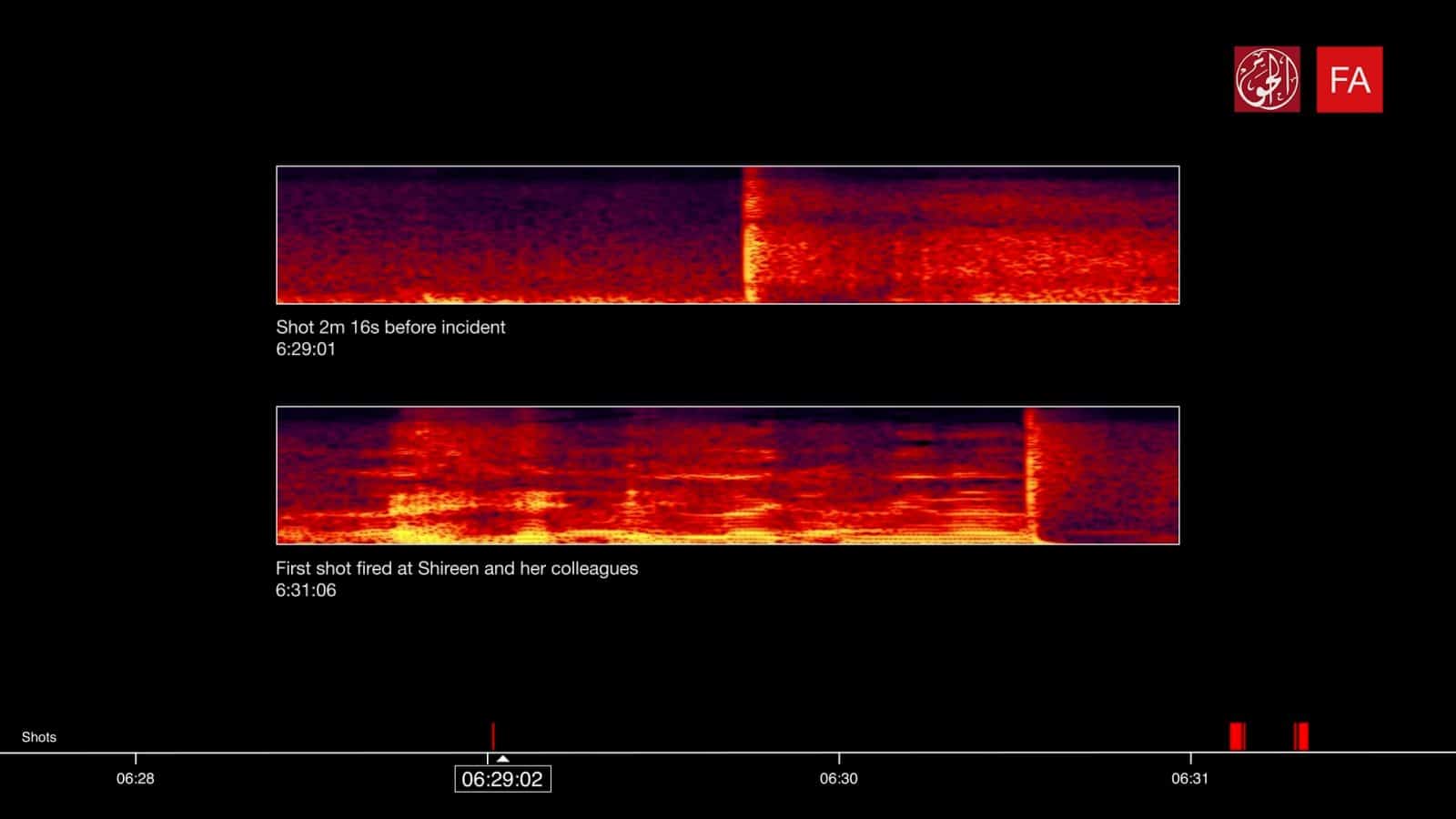

- Audio analysis

-

3D Reconstruction

In our analysis, digital models are more than mere 3D representations of real-world locations—we use 3D models as analytic or operative devices. Models help us to understand the location of images, camera positions or events in relation to one another. They also allow us to conduct new analyses based on spatial relations, including the positions of people, gunshot trajectories, and fields of vision.

Our spatial reconstruction and analyses are divided into three ‘scales’: site, scene, and incident.8 ‘Site’ describes the unmovable elements, including roads, buildings, and trees; ‘scene’ describes the locations of movable large objects such as vehicles; and ‘incident’, the relative positions and movements of all persons’ positions and of the kinetic objects involved, including shot impact points, trajectories of shots, lines of sight, and dynamic ‘cones of vision.’9

All 3D reconstruction was built using the open-source 3D software Blender. The model was also processed in the animation software Houdini to calculate the field of visibility of the marksman.- Site

- Photomatching

- Scene Scale

- Incident Scale

- Shadow analysis

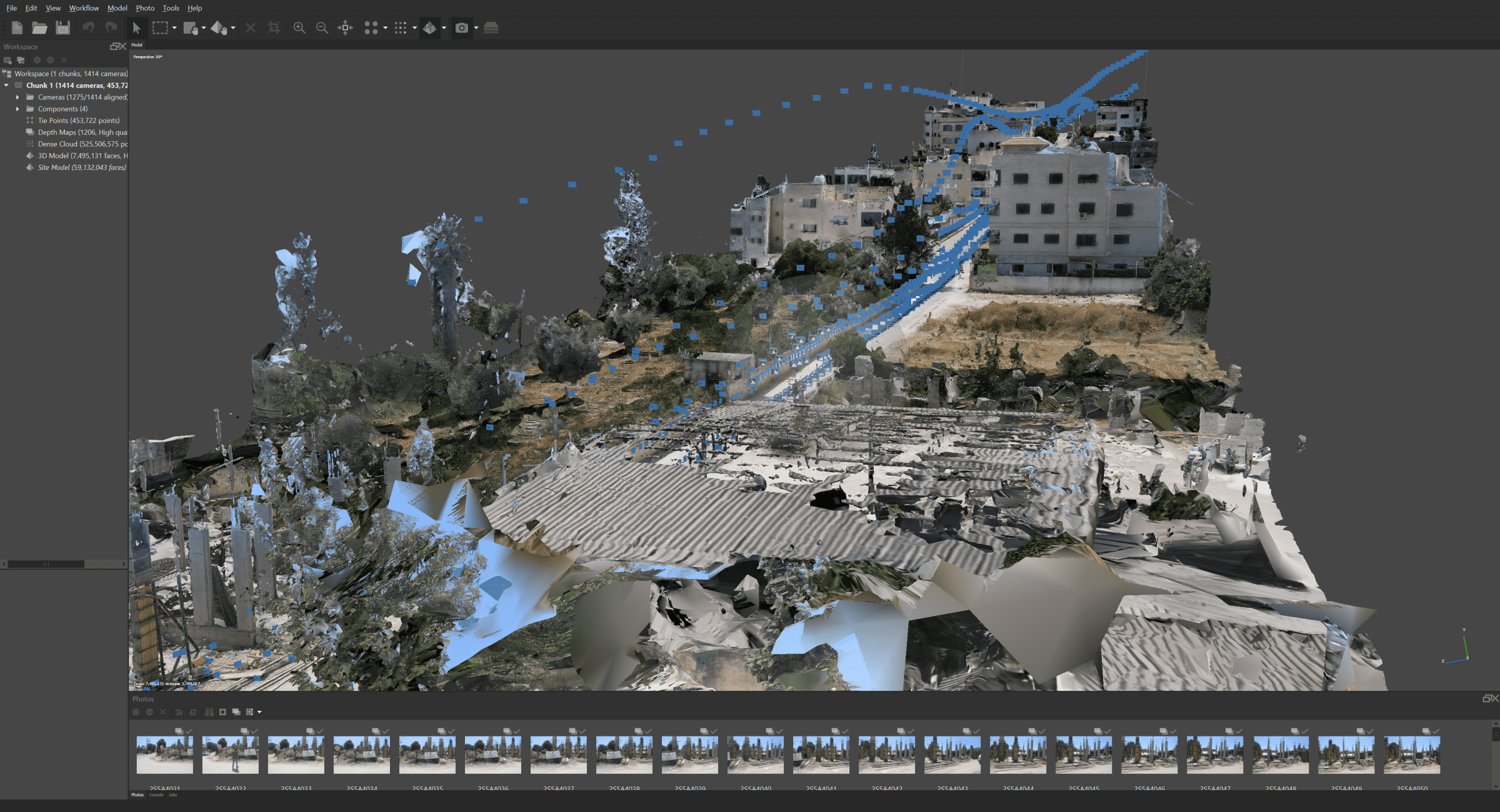

![Photogrammetry model - Photogrammetry model with location of armoured vehicle at time of shooting. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() Photogrammetry model with location of armoured vehicle at time of shooting. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

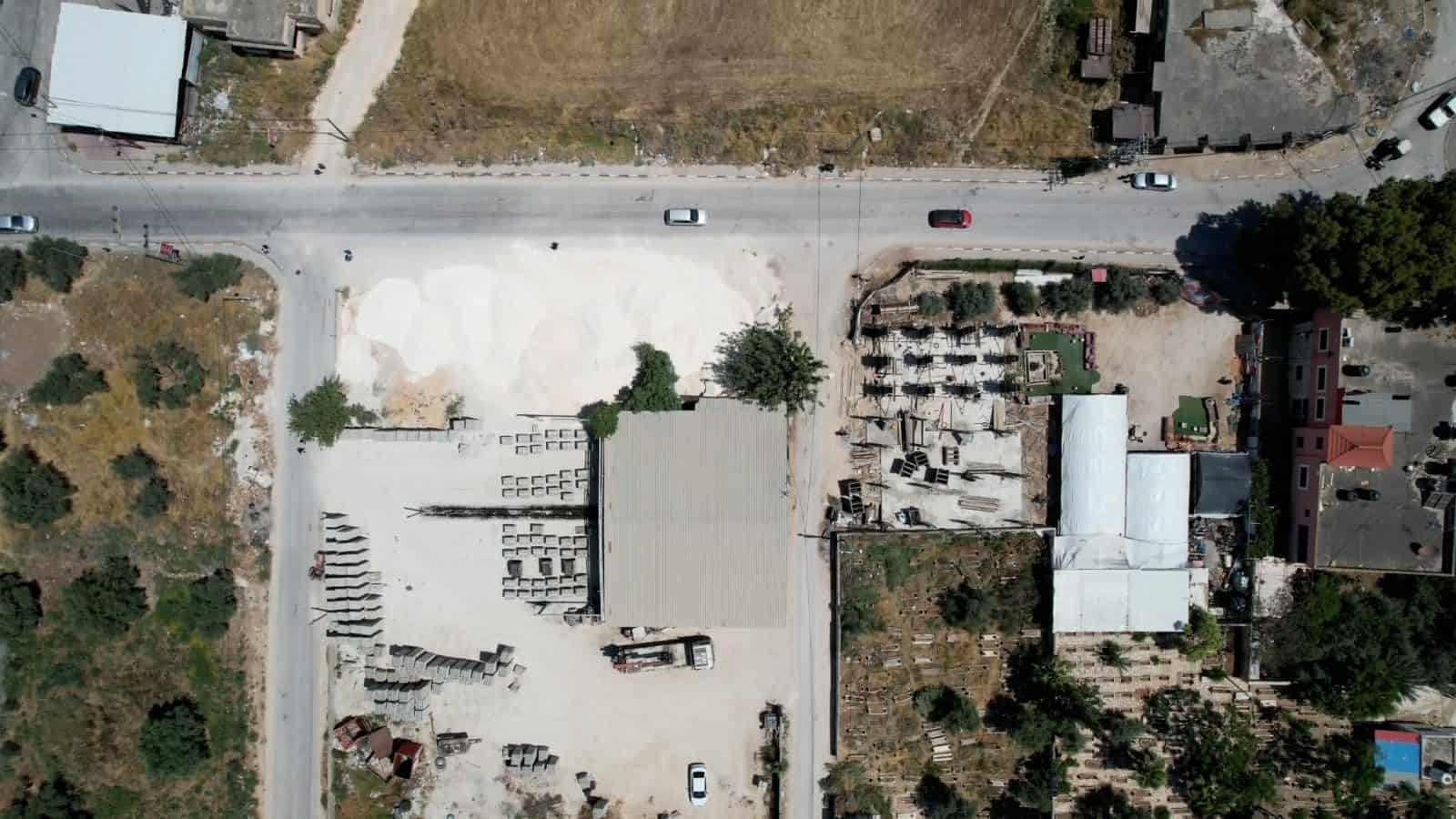

Photogrammetry model with location of armoured vehicle at time of shooting. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)We commissioned a local surveying company to conduct an extensive drone survey of the site and sourced ground photography of the entire length of the road, which allowed us to create a highly accurate 3D photogrammetry model of the site scale. Photogrammetry is a process by which large numbers of still photographs, of an object or environment, can be combined to create a precise and navigable 3D model. Photogrammetry software, such as Metashape, computes distances within a 2D image by a process of triangulation, taking into consideration metadata like the focal length of the lens of the camera that captured the image.10 Metashape then arranges every pixel from multiple overlapping images in 3D space, creating a ‘point cloud’ made of often hundreds of millions of individual pixels, or ‘points’. This point cloud can be anchored to its location in the real world, through a process known as ‘ground truthing’.11

![Photogrammetry Process - Photogrammetry software "Metashape" processing 3D model of the site. (Forensic Architecture and Al Haq, 2022)]() Photogrammetry software "Metashape" processing 3D model of the site. (Forensic Architecture and Al Haq, 2022)

Photogrammetry software "Metashape" processing 3D model of the site. (Forensic Architecture and Al Haq, 2022)We modified and added elements to this model through photographs and satellite imagery.

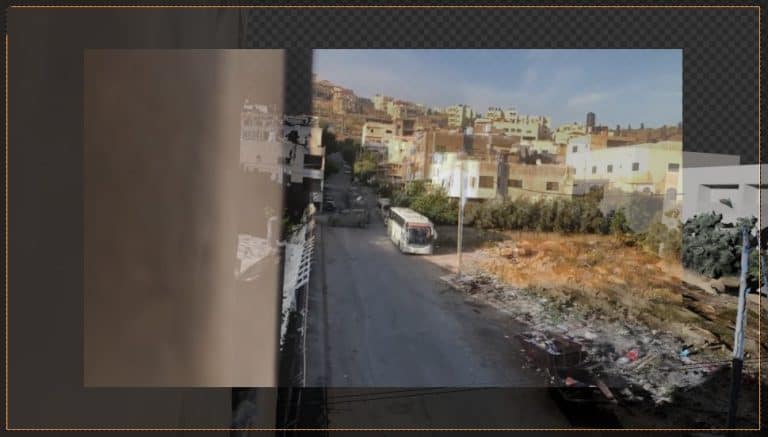

To precisely model the scene and incident from the footage, we had to first match the position, perspective, and focal lengths of all footage that captures the needed positions of analysis. We refer to the process of reconstructing the position of origin of a piece of footage and creating a simulated camera that matches it to the 3D model as ‘photomatching’ and to a single recreated image and camera as a ‘photomatch.’ Photomatching is a technique developed by Forensic Architecture through a number of investigations.12 We place the frames of a video inside our digital ‘site’ model of the scene, as a semi-transparent ‘foreground object’ in Blender. Using a ‘camera object’, a virtual parameter inside the software which simulates the view settings of a real camera, we match the same position, angle, and focal length of each footage in the 3D model. Using these simulated cameras in the 3D model, along with the corresponding footage superimposed onto the scene, we are then able to analyse the incident from multiple perspectives, including the positions of and distances between the journalists, the civilians, and the Israeli army vehicle convoy up the road.

At the level of scene, we used video stills from four different perspectives to situate the Israeli army military vehicle convoy. We studied the footage of these vehicles and used open-source research to identify the vehicles and their features. We identified the front and back vehicles as the ‘MDT David Urban Light Armoured Vehicles’. We modelled this vehicle using drawings from the manufacturer’s specifications as well as photographs of its features.13 We identified the Wolf Armoured Vehicle and purchased a precise 3D model available online after checking and verifying its precision, so that we could place it within our reconstructed 3D environment as part of the scene scale reconstruction.14

![A photo-match of IOF military jeeps]()

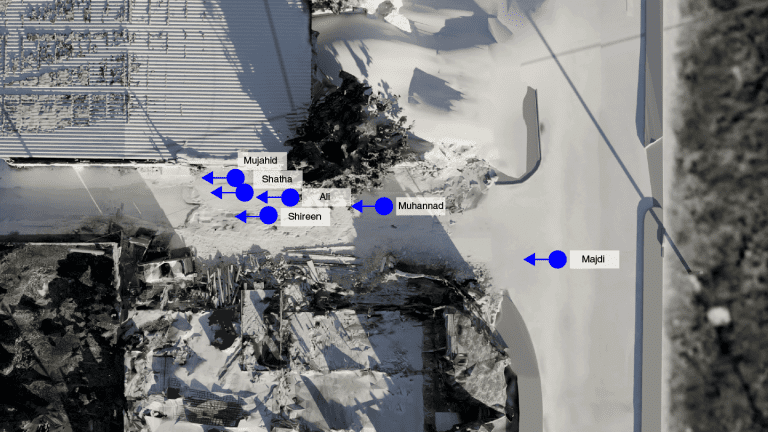

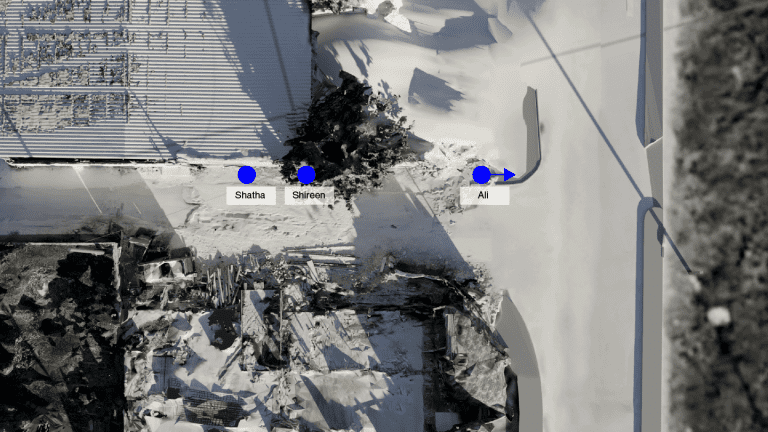

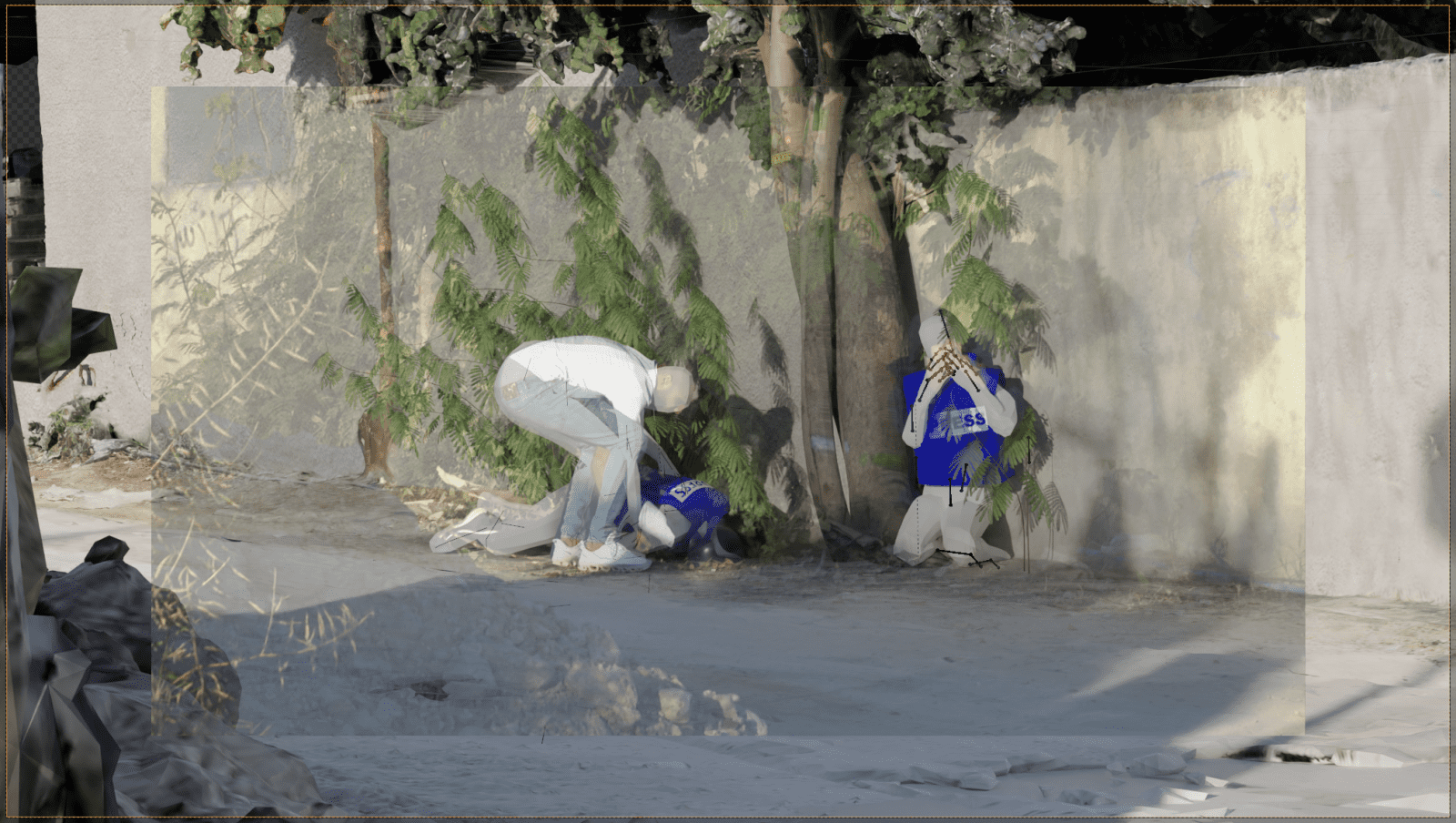

At the level of the incident, we ‘photomatched’ several stills of the incident from the ‘Al Jazeera’ and ‘16 min video’ footage in Blender which capture the position of Shireen and the other journalists present at significant moments throughout the incident.15 Through these stills, we modelled the position of Shireen, and the others present at the scene.

![Photo-match: Sharif approaches Shireen]()

To model the position of individuals that are not captured on footage, we relied on other sources. To model the position of Ali in the moment he was shot, we relied on a 3D comparative analysis interpolating between his positions captured in the footage before and after his shooting, the photographed location of his wound, and his account of the incident delivered to us.

To model the position of Shireen in the moment she was shot and the trajectory of the bullet that killed her, we studied her autopsy report, to which we had exclusive access (4.6.1). We used this together with the synchronized footage and the 3D reconstruction of the incident, including the last position we see her standing and the first time we see her on the ground.

For those videos and photographs without metadata, as well as those which contain inaccurate metadata, we determined the time they were captured through a virtual shadow analysis. For each ‘photomatch’ in the 3D modelling software, Blender, we could overlay the matched image with a semi-transparency to allow us to maintain sight of the 3D model. Blender possesses a built-in ability to accurately simulate sunlight of a precise geographic location and time of year. By specifying the location as Jenin and the date as the same as that of the incident, we used our 3D model of the site to simulate the sun’s movement until the shadow of the 3D model matches the position observed in the footage. The match of shadows thus indicates that the footage was captured at approximately the same time, within a five-minute margin of error. Doing this for footages without metadata allows us to verify their occurrence on a timeline of the day of the incident.

![Shadow Analysis]()

-

Visibility and Vision

Both the digital reconstruction and the physical on-site reconstruction of the marksman’s vision through the rifle scope, which was likely used, as per our research detailed in 5.3, show a consistent field of vision and magnification, verifying the accuracy of both methods.- Digital reconstruction

- On-site reconstruction

Our digital reconstruction of the scene includes the precise position of the Israeli army armoured vehicle parked closest to the approaching journalists and its sniper hole. Using this reconstruction, we can simulate the Israeli marksman’s view through the scope of their rifle throughout the incident, including the moments Shireen and Ali were shot. We were able to simulate accurately based on the specifications of the scope which was likely used by the marksman, following research detailed in 5.3.2.

In order to model our digital reconstruction, we placed a virtual camera object matching a 35mm camera which accurately simulates the optical magnification of the scope in the identified position of the marksman. To precisely simulate the marksman’s view, we modelled a circle within the software with a diameter of 12.27 meters. This was then placed 100 meters from the camera, and oriented perpendicular to its view. This circle, in this specific position, would occupy the full extent of the scope from the view of the camera: the area not occupied by this disc would be outside the field of view of the marksman. This process allowed us to accurately limit the extents of the view to what the marksman would have seen in their scope in both magnification and extent. We captured this perspective with multiple positions of the journalists and civilians involved including the moments when the shooting began, when Ali was shot, and when Shireen was shot.In order to conduct an analysis at the site of the incident, we took photographs at the site of the incident from the precise position of the Israeli army marksman at the time of the incident in order to reconstruct the view through the marksman’s scope at the instance of each shooting. We recreated the scene by positioning a camera of correlating specifications to the scope with individuals wearing the same ‘PRESS’ vests Shireen and Ali were wearing at the time of the incident at the various exact positions where Ali and Shireen were shot. These photographs were masked to match the marksman’s field of view described in 5.7.1. From this analysis we were able to determine the visibility of the journalists to the marksman.

- On-site Testimony

Ten of the available sources of footage on the day of the incident show the position of the Israeli army vehicle convoy at various times. This helps establish the precise position of the convoy at the time of the incident. (4.2-4.2.2, 4.3-4.3.5, 4.3.8-4.3.9)

Only two videos capture the incident of the shooting itself, 4.1.1 (henceforth ‘Al Jazeera’) and 4.2.1 (henceforth ’16 min video’). ’16 min video’ was recorded as a livestream on the social media platform TikTok by user Sleem Awad (sleemawad1995). ‘Al Jazeera’ is a video that was recorded by an Al Jazeera cameraperson during the incident. Al Jazeera provided us with the exclusive full length of the recorded footage, which was previously unpublished.

The rest of the material found online and given to us by witnesses shows the moments before and after the incident. (4.2.1,4.2.2)

The material created by the authors, 4.4.2-4.4.5, concerns on-site documentation of the impact points of bullets on a tree at the site of the incident.

4.4 and 4.4.1 are photographs by the authors taken at the site of the incident that accurately simulate the vision of the marksman through their rifle scope at the moments they shot Ali and Shireen, respectively.

We commissioned a local surveying company to conduct an extensive, professional drone survey of the site and sourced ground photography of the entire length of the road, which allowed us to create a highly accurate and geo-referenced 3D model of the scene (photogrammetry, see 5.6.1).

An audio analysis was conducted by sound expert and researcher Dr. Lawrence Abu Hamdan for Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq. See section 5 in Dr. Abu Hamdan’s accompanying report for an explanation of the method used in his analysis.

We carried out an on-site testimony with Shatha Hanaysha. Shatha was one of the journalists present when the Israeli army targeted them. She was standing near Shireen when Shireen was shot and killed.

Shatha went to the site of incident with our team and recounted what she remembered of the incident, with an emphasis on what Shatha saw and the positions of each of the journalists at significant moments during the incident.

At the site of the incident, we also measured and marked on the ground the precise position of the journalists at several significant moments (the method of identifying their position is explained in 5.6.2). We then positioned actors to stand in place of the journalists at different moments and asked Shatha questions about the movement and location of the subjects in time and space. By providing the witness with fixed and known positions, they can fill in the key gaps of what we can see and hear of the incident: particularly in moments when we do not see the journalists in the footage. We do this also with the understanding that when witnesses are positioned in precisely the same locations they were during the incident, they can recall more easily the details of the incident.16

6. Timeline of Incident

- 6:28:25: We can see (video 4.2) Shatha and Mujahid al-Saadi are standing at the intersection of Balat Al Shuhada’ street and the end of the street where the Israeli army vehicles were stationed for the raid on Jenin Refugee Camp.

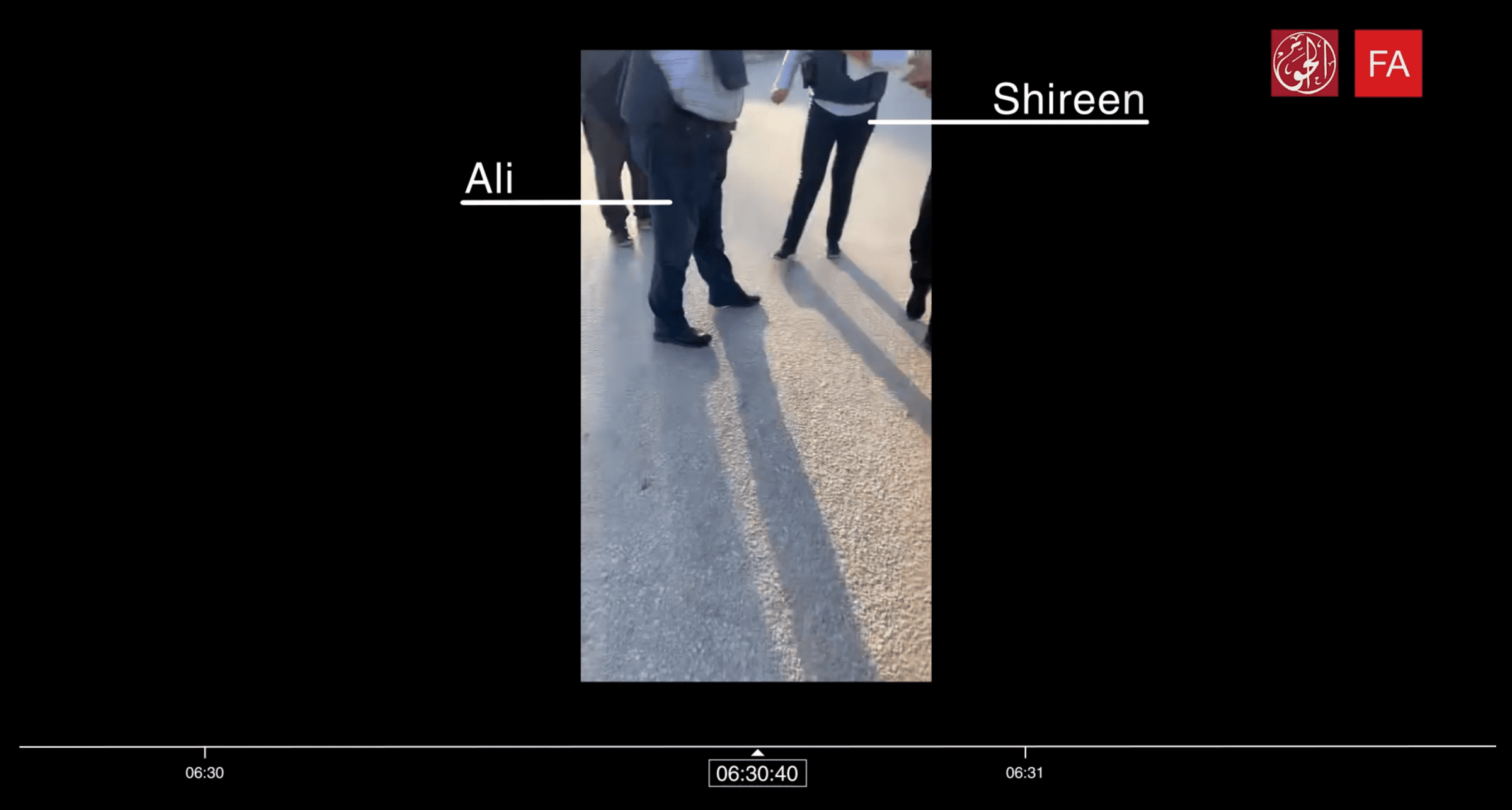

- 6:30:40: Nearby, Shireen and Ali begin walking towards that same intersection where Shatha and Mujahid are standing.

- 6:30:49: Shireen and Ali are joined by Shatha, Mujahid, with Muhannad Nairoukh and Majdi Bannoura behind them, as they begin slowly walking up the road toward the Israeli army position, following standard press protocols for self-identification.

- 6:31:00: Muhannad also begins to walk slowly up the same road toward the Israeli army position.

- 6:31:06 – 6:31:09: After walking toward the army position for approximately 1 minute 20 seconds, the incident begins with the first round of shooting with 6 single shots fired at the journalists in rapid succession from the Israeli army position.

- 6:31:13: 4 seconds after the first round of shooting ends, we see Ali (4.1) running in the opposite direction, seeking cover and shouting ‘I am wounded, I am wounded.’ [translation]

- 6:31:12 – 6:31:18: We can see that Shireen was hiding by the wall during this time.

- 6:31:17- 6:31:19: 8 seconds after the first round of shooting ends, a second round begins with 7 shots, again fired in rapid succession. Shireen was killed during this round.

- 6:31:18: We identified the last moment Shireen is seen still standing, crouching near the wall, after the first shot of the second round.

- 6:31:24: We hear Shatha call for an ambulance

- 6:31:38: We first see Shireen on the ground. We also see Shatha hiding behind the adjacent tree, unable to reach her or provide her with aid.

- 6:32:13: A minute after Shireen is shot, a civilian, Sharif, tries to cross the road to provide first aid to Shireen but holds back from crossing the street for fear of being targeted.

- 6:33:05: Another minute later, the same civilian, Sharif, manages to find a way around the road, climbs down from the wall adjacent to Shatha, and attempts to reach Shireen.

- 6:33:12: Sharif begins to approach Shireen.

- 6:33:19: As Sharif approaches Shireen and attempts to provide her with first aid, the first shot of the third round is fired at him by the Israeli army marksman.

- 6:33:21: Sharif is forced to run back to the wall and hide behind the tree with Shatha to avoid the gunfire.

- 6:33:25: Sharif approaches Shireen again but hesitates presumably out of fear of being targeted.

- 6:33:29 – 6:33:34: Sharif helps Shatha escape the scene.

- 6:33:38: Sharif returns for a second time to attempt to provide aid to Shireen.

- 6:33:42: Sharif is shot at again by the Israeli army.

- 6:33:44: Sharif is shot at a third time by the Israeli army

- 6:33:44 – 6:34:24: Sharif manages to carry Shireen away from the site to cover and with the help of other civilians takes her to the Ibn Sina hospital in Jenin

7. Analysis

-

Shireen and the other journalists were clearly identifiable as such to the Israeli army marksman.

-

The journalists followed standard protocols for self-identification. We determined this through video analysis of the incident and the testimony of Shatha Hanaysha.

- In ‘16 min video’, we observe that between 6:30:49 and 6:31:06, when the first round of shooting begins, the journalists (Shireen, Ali, Shatha, Mujahid, Muhannad and Majdi) are walking in the direction of the Israeli army position, moving along the middle of the road, each of them wearing standard press vests with the word ‘PRESS’ written on the front and back of their vests with a dimension of 21.5 cm by 4.5 cm. The journalists are seen wearing plain clothes and not carrying anything in their hands, thus clearly identifiable as civilian non-combatants.

- Our interview with Shatha Hanaysha verified the precise steps the journalists took as they approached the Israeli army position, including standing at the end of the road for several minutes. The journalists followed standard practices as carried out by Palestinian journalists in the occupied territory, as well as standard protocols of identification in line with recommendations by UNESCO and Reporters Without Borders.17 We can confirm Satha’s statement since they are visible, in ‘16 min video’, standing at the end of the road at 06:28:25, 3 minutes before the incident.

-

The shooter was an Israeli army marksman using a standard M4 Carbine equipped, most likely, with a 4x magnification scope. We determined this through open-source research and Shireen’s autopsy report.

![M4 with trijicon scope - M4 Carbine equipped with a trijicon ACOG 4x magnification riflescope]() M4 Carbine equipped with a trijicon ACOG 4x magnification riflescope

M4 Carbine equipped with a trijicon ACOG 4x magnification riflescope- Using Shireen’s autopsy report and open-source research, we identified the bullet retrieved from Shireen’s skull was identified as being a 5.56mm bullet with a green tip. Through a process of open-source research detailed in 5.3, we were able to determine that such bullets are standard ammunition of Israeli army marksmen. These bullets are more accurate than regular bullets and, given their increased penetrability, more deadly.

- The Israeli army convoy was composed of five vehicles, including one at the front and one at the back of the convoy which were parked perpendicular to the road. These two vehicles on the edges of the convoy are armoured, so as to protect them against small fire, and have a ‘sniper hole’ on the side. One of such ‘sniper holes’ faced the road where the journalists were. The placement of the army vehicles (see image below) supports a practice whereby marksmen sit inside such vehicles ‘guarding’ the flanks.

- Using open-source research, we were able to determine that the unit reportedly present in Jenin on the day of the incident, the Duvdevan special unit, is commonly equipped with rifles with an optical scope which magnifies the marksmen’s vision by 4x. This fact, together with the specifications of the armoured vehicles, and the standard positioning protocols of the Duvdevan unit, allowed us to recreate the field of vision of the marksman who was positioned at the north vehicle’s sniper hole. This way, we could analyse what was and what was not visible to them.

![bullet with green tip - Bullet retrieved from autopsy is 5.56mm bullet with a green tip, the same bullet used by marksmen]() Bullet retrieved from autopsy is 5.56mm bullet with a green tip, the same bullet used by marksmen

Bullet retrieved from autopsy is 5.56mm bullet with a green tip, the same bullet used by marksmen![5 Vehicles stationed - Front and back IOF armoured vehicles stationed sideways pointing its shooting hole down the road towards the journalists 190m away]() Front and back IOF armoured vehicles stationed sideways pointing its shooting hole down the road towards the journalists 190m away

Front and back IOF armoured vehicles stationed sideways pointing its shooting hole down the road towards the journalists 190m away -

The journalists’ ‘PRESS’ sign on their vests was clearly visible from the position and through the rifle scope of the marksman both when they began shooting and throughout the incident, including when Ali and Shireen were hit.

We determined this through reconstruction based on digital modelling, physical reconstruction and optical analysis (as explained in 5.7 and 5.7.3).- In our digital modelling, detailed in 5.7.1, we were able to create a 3D model which accurately reflected the field of vision of the marksman from the sniper hole. Using this reconstruction, with its simulation of the position of the marksman’s rifle scope and its likely magnification, and positioning Shireen and Ali’s digitally reconstructed bodies in the positions and moments when they were shot, we were able to accurately reconstruct the view through the scope in these instances. In these views, Shireen and Ali are clearly identifiable both as journalists – given the size and orientation of their vests, the ‘PRESS’ sign is clearly visible at all times – and visibly unarmed – their hands are within the field of vision of the marksman, and empty.

- We further conducted a physical reconstruction of the event to verify the digital reconstruction, as detailed in 5.7.2, using photographs at the site of the incident from the marksman’s precise position. The photographs were cropped following the mask described in 5.7.1, and are an accurate recreation of the view of the marksman at the times when Shireen was fatally shot and Ali, wounded. In these views, as in the digital reconstruction, Shireen and Ali are clearly identifiable as unarmed journalists.

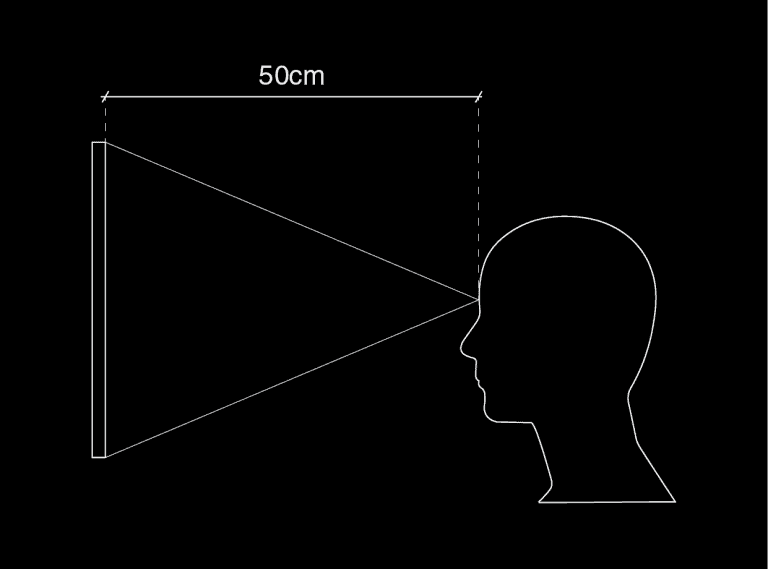

- In the attached video report, we enlarged this view to the height of the video frame to represent the resolution of the marksman’s vision more accurately. To view both digital and optical images at the same relative size as what the marksman would have seen, the images should be viewed on a 27” monitor at full screen with the viewer sat 50cm away. This position would replicate the marksman’s view, through 32mm scope lens placed 1.5 inches from their eye.

![Digital reconstruction of shooter’s view - Digital reconstruction of the visibility of the journalists as they were walking up the road. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() Digital reconstruction of the visibility of the journalists as they were walking up the road. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

Digital reconstruction of the visibility of the journalists as they were walking up the road. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)![Optical reconstruction of shooter’s view_Shireen - On site visual reconstruction of Shireen's visibility the moment she was shot. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() On site visual reconstruction of Shireen's visibility the moment she was shot. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

On site visual reconstruction of Shireen's visibility the moment she was shot. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)![Screen Diagram - Diagram showing correct viewing distance of images on a 27inch screen, to accurately replicate the view of the marksman at the time of shooting - replicating the 32mm scope lens placed 1.5 inches from their eye.]() Diagram showing correct viewing distance of images on a 27inch screen, to accurately replicate the view of the marksman at the time of shooting - replicating the 32mm scope lens placed 1.5 inches from their eye.

Diagram showing correct viewing distance of images on a 27inch screen, to accurately replicate the view of the marksman at the time of shooting - replicating the 32mm scope lens placed 1.5 inches from their eye.

-

The journalists followed standard protocols for self-identification. We determined this through video analysis of the incident and the testimony of Shatha Hanaysha.

-

The Israeli army deliberately and repeatedly targeted Shireen and her fellow journalists with the intention to kill.

-

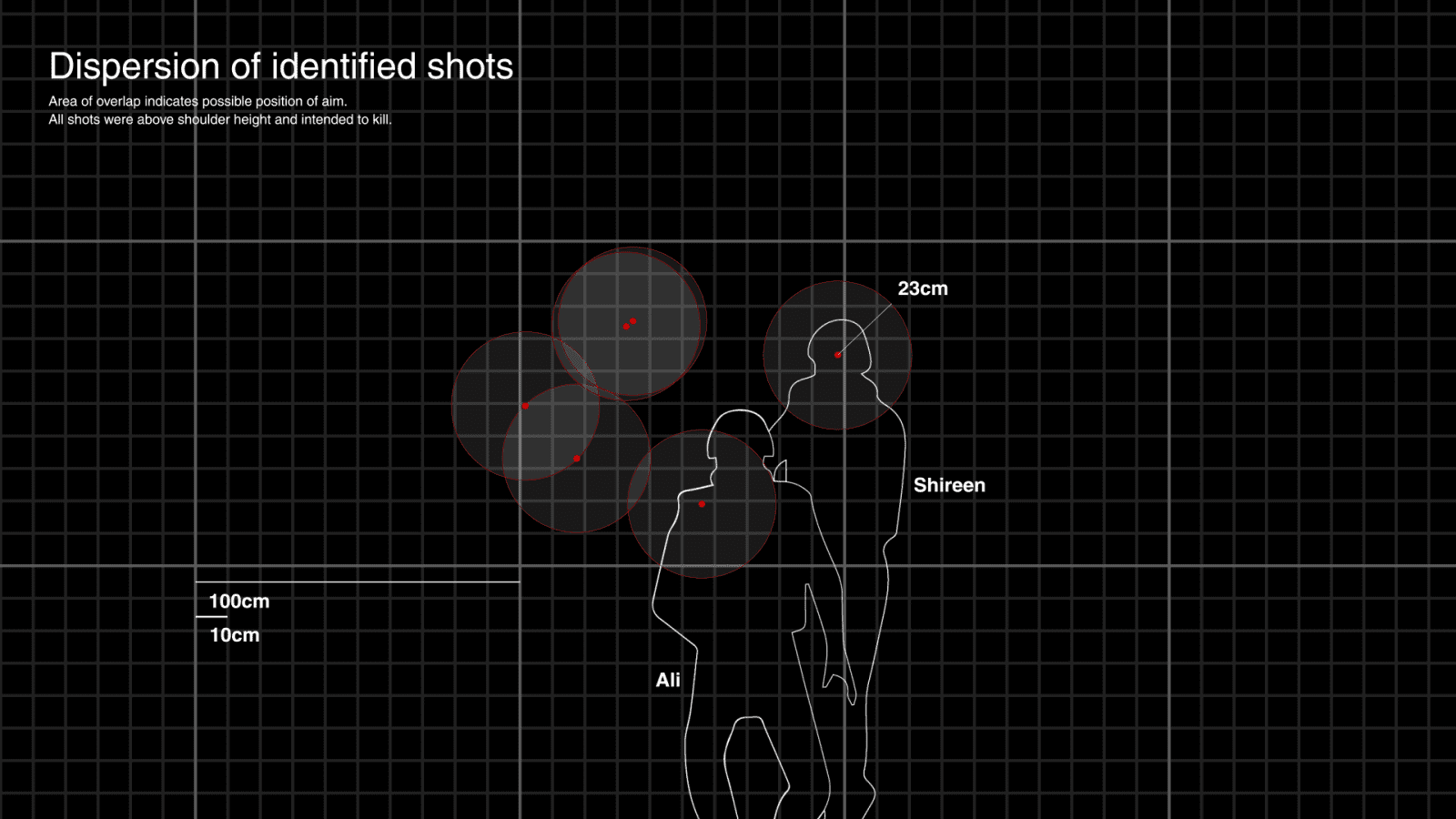

Trajectory analysis of the shots fired reveals: (i) a clear line of fire to the group of journalists from the Israeli army position, (ii) close proximity of the shooting’s impact points, and (iii) that all impact points were above shoulder height, together indicating the precise aim of shots with the intention to kill.

We determined this using 3D reconstruction, video analysis, and analysis of open-source weapon specifications.- We photomatched photographs documenting the tree which was used as protection from the gunfire by Shireen and Shatha, and the bullet impact points which can be seen in its trunk in our 3D model (5.6). These also appear in the photogrammetry model in their precise positions. In analysing the photographs of the tree at the site of the incident, we identified four bullet impact points at a close distance to one another.

- We reconstructed Ali’s position by referencing two sources; the first and primary source was Ali’s testimony of where he was standing when he felt he was shot. The second source was arrived at through the interpolation between two confirmed and modelled positions: one when the first round of shooting began at 06:31:06 from ‘16 min video’; and one after the first round of shooting ended, when we see Ali running to a car at 6:31:13 in the ‘Al Jazeera’ video.

- We confirmed that the position he testified to be in when he was shot is consistent with being between the two confirmed and modelled positions before and after the shooting that we reconstructed from the footage. His movement between these two positions also provides an account of his body’s rotation. We increased the precision of his position by studying photographs of his injury then positioning the modelled figure representing Ali, so that his wound location and the modelled trajectory from the Israeli army marksman align in direction.

- To locate the impact point that hit Shireen, we first photomatched a still from ‘Al Jazeera’ at 6:31:37, after Shireen was shot and had fallen on the ground. From this match in the model, we modelled the precise position of Shireen on the ground. This model allowed us to recreate Shireen’s approximate standing location when she was shot, by positioning a standing figure at the feet of her fallen position. We further refined Shireen’s position and the impact point by analysing the autopsy to precisely establish the points where the bullet entered and exited Shireen’s head. We adjusted the position of the figure representing Shireen and the trajectory line from the Israeli army marksman so that they aligned in direction, thus creating an accurate model of the moment she was fatally shot.

- Locating the impact points of the tree on the site directly adjacent to where Shireen was shot, the impact point that hit Ali, and the point where Shireen was shot, all allowed us to draw trajectory lines of the shots between those points and the Israeli armoured vehicle. These reconstructed shot trajectory lines demonstrate a clear line of fire from the Israeli army vehicle sniper hole.

- We modelled the markings of the six identified impact points out of the 16 shots fired. Using the 3D model, we projected these impact point markings onto a flat orthographic surface projection perpendicular to the trajectories of the shots, to study the distance between the impact points.

- Specifications of the rifle state the M4 Carbine rifle has a shot deviation of 12 cm per 100 m.18 At 190 meters, which is well within the range of efficiency recommended for these rifles, the shots can therefore deviate 23 cm from the target of aim. In analysing the proximity and aim of the shots, we drew a circle with a 23 cm radius around each shot to reveal the possible area of aim for each shot. The radiuses of four of the six shots overlap, therefore indicating common areas of possible aim. Two of the six shots on the tree are less than 5 cm apart in impact.

- The proximity of the documented impact points thus reveals precise and careful aim of shots fired over the course of three rounds.

![tree photomatch - Photomatched image of the tree with 4 bullet marks. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() Photomatched image of the tree with 4 bullet marks. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

Photomatched image of the tree with 4 bullet marks. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022) -

All shots were fired above shoulder height and indicate an intention to kill.

- The projection of confirmed that the shots’ impact points (as explained in 7.2.1.6-7.2.1.8) are positioned above the shoulder height of Ali, Shireen and the rest of the journalists. We determined this by projecting the outline of Shireen and Ali in their reconstructed positions when they were shot onto an orthographic plane and comparing them with the locations of the shots. Journalists’ vests are armoured, and therefore, shots fired above shoulder height are intended to kill because they are aimed at areas of the body which are less protected, like the neck and the lower half of the head.

-

A field of vision analysis simulating the view from the rifle scope reveals that shots were only fired when journalists, and later a civilian, were within the line of sight of the Israeli army marksman.

- We used the 3D reconstruction of the site to define the field of vision available to the marksman from the armoured vehicle’s left sniper hole. We did that by extending the cone of vision from the marksman’s scope and studying what would be visible and what would hidden within the marksman’s view cone (also known as ‘white shadows’) by different obstructions such as buildings, walls, vehicles, and trees. We did this by first creating a 3D grid of points 5cm apart within the view cone and then extending rays from the marksman’s rifle scope to each point. We wrote an algorithm processed in the Houdini modelling software that analyses the intersections of these rays (lines of sight) with objects in the 3D model. Rays that do not intersect with any object in the model indicate a clear line of vision to a particular point. These unobstructed lines of vision form what we refer to as the marksman’s field of vision.

-

Based on the reconstruction of the marksman’s field of vision described above, we studied the possible relations between the timing of the shots and the presence of the journalists, and later a civilian, within the marksman’s view. This analysis shows that the marksman fired shots only when these individuals were within their field of vision.

- This is especially clear when a civilian, Sharif, attempts to reach and provide first aid to Shireen. Our field of vision analysis clearly indicates that the three shots fired at Sharif while attempting to provide aid to Shireen happened immediately after he enters the field of vision of the marksman. No shots were fired when Sharif and Shatha were hiding behind the tree and outside the marksman’s field of vision (See video below, also section 6 for detailed timeline).

-

Video synchronisation reveals three distinct rounds of fire, which continued as the journalists sought shelter and attempted to run and seek cover.

- In the synchronised combined footage of ‘Al Jazeera’ and ’16 min video’ we were able to analyse and distinguish each shot fired. The audio and acoustic analysis confirms 16 shots fired from the Israeli army position across three distinct rounds of fire. The first round contained six shots, the second round, seven: and the third round, three shots. (See Audio and Acoustic Report by Dr. Lawrence Abu Hamdan)

-

During the second round of fire, the shooting likely continued until Shireen was hit, supporting the assessment that she was the target of this round.

- In ’16 min video’ we identified the last time Shireen is seen standing at 6:31:18, after the second round of shooting began with one shot having already been fired.

- We modelled the position of Shireen at this moment and compared it to where she fell to the ground. The distance between her position after the first shot of the second round and her position when she was shot was 3 meters. The last shot of the second round was fired just 1.5 seconds after Shireen is seen alive, which is the last possible shot to hit Shireen. The distance travelled by Shireen before she was shot makes it likely she was hit in one of the last three shots of the second round of shooting because of the time required to cross that distance.

- That Shireen was likely hit in one of the last three shots of the second round supports the assessment that the Israeli army marksman continued firing until Shireen was hit and that she was the target of this round.

![Dispersion of shots - By projecting the gunshots onto a single plane, set against the locations of Ali and Shireen when they were shot, we were able to demonstrate the precision and proximity of the shots and their consistent positioning at above-shoulder height, indicating intent to kill. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() By projecting the gunshots onto a single plane, set against the locations of Ali and Shireen when they were shot, we were able to demonstrate the precision and proximity of the shots and their consistent positioning at above-shoulder height, indicating intent to kill. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

By projecting the gunshots onto a single plane, set against the locations of Ali and Shireen when they were shot, we were able to demonstrate the precision and proximity of the shots and their consistent positioning at above-shoulder height, indicating intent to kill. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022) -

Trajectory analysis of the shots fired reveals: (i) a clear line of fire to the group of journalists from the Israeli army position, (ii) close proximity of the shooting’s impact points, and (iii) that all impact points were above shoulder height, together indicating the precise aim of shots with the intention to kill.

-

The attack against Shireen and her fellow journalists was unprovoked.

-

Video analysis confirms there were no other persons present between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.

![No other persons between the journalists and the military vehicles - Video analysis confirms there were no other persons present between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.]() Video analysis confirms there were no other persons present between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.

Video analysis confirms there were no other persons present between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.- Four videos capture the street between the journalists and the Israeli army position, including the military vehicles, in the moments shortly before and after the incident. These videos are ’16 min video,’ which captures the entire street 3 minutes before the incident; ‘Telegram_Jenin_Vehicles 1’ which captures the street and military convoy around 2 minutes before the incident; ‘Balcony video 01’ which captures the military vehicles approximately 9 minutes before the incident; and ‘Balcony video 02’ which captures the area around the military vehicles approximately 16 minutes after the incident. All these located videos were timed according to metadata and shadow analysis (5.6). All these videos demonstrate that no others were present between the military vehicles and the journalists.

-

Witness testimony confirms that there were no other persons between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.

-

We went to the site of the incident with Shatha Hanaysha and interviewed her about the incident. We marked several known locations of her person at different stages of the incident and asked her to fill in the gap of what happened between those known positions and times. This allowed for a better memory recollection and more accurate testimony. We started by asking Shatha about what she observed as she was standing at the end of the road with Mujahid al-Saadi and leading up to the moments of the first round of shooting. Shatha confirmed she did not see anyone between them (the journalists and some civilians) and the Israeli army position. She also said that they did not hear any gunfire nor see any fighters or fighting near them at any point; and that if they had, they would not have walked in the direction of the Israeli army position. The following is a quote included in our accompanying video report:

“Until we started moving, there weren’t any gunshots heard, even from afar. There weren’t any gunshots near us, something that would scare us away; the situation was very calm.”

-

We went to the site of the incident with Shatha Hanaysha and interviewed her about the incident. We marked several known locations of her person at different stages of the incident and asked her to fill in the gap of what happened between those known positions and times. This allowed for a better memory recollection and more accurate testimony. We started by asking Shatha about what she observed as she was standing at the end of the road with Mujahid al-Saadi and leading up to the moments of the first round of shooting. Shatha confirmed she did not see anyone between them (the journalists and some civilians) and the Israeli army position. She also said that they did not hear any gunfire nor see any fighters or fighting near them at any point; and that if they had, they would not have walked in the direction of the Israeli army position. The following is a quote included in our accompanying video report:

-

Sound analysis of videos of the incident confirms that the only shots fired in the three minutes preceding the shooting of Shireen came from the Israeli army’s position.

![Audio analysis – comparison of shots - Audio analysis of the videos capturing the incident allowed us to compare the sound signatures of all shots fired during and preceding the incident and trace them back to the IOF marksman’s position. In the two minutes before the shooting begins, no shots are fired at all. No other shots in any of the footage analysed came from the vicinity of the journalists. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)]() Audio analysis of the videos capturing the incident allowed us to compare the sound signatures of all shots fired during and preceding the incident and trace them back to the IOF marksman’s position. In the two minutes before the shooting begins, no shots are fired at all. No other shots in any of the footage analysed came from the vicinity of the journalists. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)

Audio analysis of the videos capturing the incident allowed us to compare the sound signatures of all shots fired during and preceding the incident and trace them back to the IOF marksman’s position. In the two minutes before the shooting begins, no shots are fired at all. No other shots in any of the footage analysed came from the vicinity of the journalists. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)- See section 2 in the accompanying Audio and Acoustic Analysis Report.

-

No other shots in any of the footage analysed came from the vicinity of the journalists.

- See 2.3, 3.5, and 4.4 in the accompanying Audio and Acoustic Analysis Report for an analysis of the shots before during and after the incident.

-

Analysis of the journalists’ movements suggest they felt safe enough to walk slowly towards the military vehicles.

- ’16 min video’ captures Ali and Shireen beginning to walk slowly toward the Israeli army position at 6:30:49. Ali says, at 6:30:43, that they “will walk directly in their direction” to make themselves clearly visible and identifiable.

- We see in the same video that Shireen, Ali, Shatha, Mujahid, Muhannan, and Majdi are slowly walking toward the Israeli army position spread apart and slowly, before the first round of shooting begins at 6:31:06. This confirms Shatha’s testimony that they were calm and unafraid as they walked.

-

Video analysis confirms there were no other persons present between the journalists and the convoy of military vehicles at the time of the incident.

-

Shireen was deliberately denied first aid after being shot.

-

Video, audio and spatial analysis confirms that while attempting to provide aid to Shireen, Sharif, a civilian on the scene was shot at each time he attempted to reach her and entered the line of sight/fire of the Israeli army shooter.

- From our footage synchronization, we see in ‘Al Jazeera’ that at 6:33:12, Sharif approaches Shireen after she was shot and had fallen to the ground. As soon as Sharif approaches her, there is a shot from the Israeli army position toward him, at 6:33:19. Sharif runs for cover and helps Shatha Hanaysha leave the scene. At 6:33:38, when Sharif approaches Shireen again to aid her, he is shot at by the Israeli army two more times, at 6:33:42 and 6:33:44. (see section 6 for a detailed timeline).

- We can confirm, through audio analysis, these shots are coming from the same place as shots fired in the first and second rounds.

- We modelled Sharif’s at the moments of the three shots fired at him, as well as two positions when he sought cover (see 5.6.2. for modelling positions method). We compared these modelled positions with the field of vision analytical model which demonstrates that the Israeli army marksman deliberately denied Shireen first aid (as explained in 7.2.3 and 5.6).

-

Video, audio and spatial analysis confirms that while attempting to provide aid to Shireen, Sharif, a civilian on the scene was shot at each time he attempted to reach her and entered the line of sight/fire of the Israeli army shooter.

8. Summary of Findings

- Shireen and her journalist colleagues were clearly identifiable as journalists to the Israeli army marksman.

- The Israeli army deliberately and repeatedly targeted Shireen and her fellow journalists with the intention to kill.

- The attack on Shireen and her journalist colleagues occurred during a period without risk to the Israeli army marksman’s life or that of other soldiers. There were no shots other than those of the Israeli marksman fired at the time and no armed individuals in the vicinity of the journalists.

- Shireen was deliberately denied first aid after being shot.

9. About Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq

- Forensic Architecture

- Al-Haq

- The 1986 Fayez A. Sayegh Memorial Award;

- The 1986 Rothko Chapel Award for Commitment to Truth and Freedom;

- The 1989 Carter-Menil Human Rights Foundation Prize;

- The 1990 Reebok Award to Shawan Jabarin;

- The 2010 Geuzenpenning Prize for Human Rights Defenders;

- The 2010 Welfare Association’s NGO Achievement Award;

- The 2011 Danish PL Foundation Human Rights Award;

- The 2018 Human Rights Prize of the French Republic;

- The 2019 Human Rights and Business Award;

- The 2020 Gwynne Skinner Human Rights Award;

- The 2021 Award of the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA);

- The 2022 Bruno Kreisky Award for Human Rights.

Forensic Architecture (FA) is a research agency, based at Goldsmiths, University of London, investigating human rights violations including environmental destruction and violence committed by states, police forces, militaries, and corporations. FA has undertaken more than eighty investigations worldwide including in Pakistan, Indonesia, Myanmar, Guatemala, Mexico, Chile, Brazil the US, UK, Germany, Turkey, Ukraine and Greece. FA is directed by Professor Eyal Weizman and works to develop new evidentiary method and apply them in complex multimedia spatial analyses. The agency also works regularly with local and international NGOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Doctors without Borders, the ICRC, and the UN.

Our investigations employ pioneering techniques in spatial and architectural analysis, open-source investigation, digital modelling, and immersive technologies, as well as documentary research, situated interviews, and academic collaboration. Findings from our investigations have been presented in national and international courtrooms, parliamentary inquiries, and exhibitions at some of the world’s leading cultural institutions and in international media, as well as in citizen’s tribunals and community assemblies.

FA’s case files have been submitted as evidence in national legal processes across the world, including in Israeli courts. The agency’s findings have also been submitted or presented in international jurisdictions including the European Court of Human Rights and the UN General Assembly, and in national courtrooms, parliamentary inquiries, and truth commissions around the world.

Forensic Architecture has been recognised for its work in the field of journalism with a Peabody Award for Digital and Interactive Storytelling (2021), the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) Princess Margriet Award for Culture (2018), the Designboom Design Prize for Social Impact (2019), and a Peabody-Facebook Futures of Media Award for Interactive Storytelling (2017). FA director Eyal Weizman is a life fellow of the British Academy and recipient of an MBE for ‘services to architecture’. He is a member of the Technology Advisory Board of the International Criminal Court in The Hague and is on the board of the Centre for Investigative Journalism.

Al-Haq is an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organization based in Ramallah, West Bank. Established in 1979 to protect and promote human rights and the rule of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the organization has special consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council.

Al-Haq documents violations of the individual and collective rights of Palestinians in the OPT, irrespective of the identity of the perpetrator, and seeks to end such breaches by way of advocacy before national and international mechanisms and by holding the violators accountable. The organization conducts research; prepares reports, studies and interventions on breaches of international human rights and humanitarian law in the OPT; and undertakes advocacy before local, regional and international bodies. Al-Haq also cooperates with Palestinian civil society organizations and governmental institutions in order to ensure that international human rights standards are reflected in Palestinian law and policies. The organization has a specialized international law library for the use of its staff and the local community. Al-Haq is the winner of twelve prestigious international awards, including amongst others:

Al-Haq is the West Bank affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists – Geneva and is a member of the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR-Net), the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network (EMHRN), the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Habitat International Coalition (HIC), the Palestinian Human Rights Organisations Council (PRHOC), and the Palestinian NGO Network (PNGO).

10. Case File Examples of Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq

- Forensic Architecture

-

Al-Haq

- Situation in the State of Palestine (investigation): This is an international criminal investigation into war crimes and crimes against humanity, Al-Haq and partners, Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, Al Mezan and Al Dameer, have submitted eight substantial communications to the Office of the Prosecutor. On 16 March 2020, the Palestinian human rights organisations Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR), Al-Haq Law in the Service of Man (Al-Haq), Al Mezan Center for Human Rights (Al Mezan), and Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights (Al-Dameer) submitted their joint observations to the Pre-Trial Chamber of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

- Salah Hammouri v NSO Group (5 April 2022): The case of Salah Hammouri v NSO Group is a criminal case, involving a breach of the right to privacy of Salah Hammouri under French law. The criminal complaint is against the Israeli company NSO Pegasus spyware used to infiltrate French- Palestinian human rights defender Salah Hammouri’s phone. The case is being conducted in France and an investigation has been opened in Paris. Al-Haq has supported with joint work with Citizen Lab, and also more broadly with campaign materials.

- MF Case: Between January and February 2022, in the case of the case of MF (March 2022) Al-Haq contributed materials and proofed a filing for accuracy of apartheid arguments, before an Immigration Tribunal in the UK. On 4 March 2022, a United Kingdom (UK) based immigration tribunal allowed the appeal of a 22-year-old Haredi Jewish rabbinical student from Israel on the basis that returning him to Israel would subject him to inhuman and degrading treatment by the Israeli authorities. The Tribunal based its findings on the likelihood that the client ‘MF’ would suffer a serious relapse of his mental health condition should the UK authorities return him to Israel. The evidence of an existing apartheid regime practiced by the State of Israel against the Palestinian people inlcuded reports from Al-Haq, amongst others.

- David Mivasair And Khaled Mouammar v. The Canadian Zionist Cultural Association (January 2022): On 11 January 2022, Mivasair and Mouammmar, the complainants, submitted an addendum to the legal complaint they had submitted in July 2022 to the Compliance Division of the Charities Directorate of the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). In the complaint, the plaintiffs requested an audit of the Canadian Zionist Cultural Association (CZCA), under well-grounded allegations of use of charitable funds for the benefit of the Israeli Occupation Forces, in violation of Canadian law. Al-Haq had supported the submission of the complaint by highlighting evident and systematic breaches of international law in the course of the Israeli military operations, which resulted in serious war crimes and crimes against humanity.

- Lawyers for Palestinian Human Rights complaint to the UK NCP about JC Bamford Excavators Limited (January 2021): On 12 November 2021, the British construction equipment company, JCB, was found by a UK Government body to be in breach of its human rights responsibilities under the government-backed OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Al-Haq along with B’Tselem; and the UK charity, EyeWitness to Atrocities submitted video, photographic and written contemporaneous evidence to substantiate the material and prolific use of JCB products in a number of specific demolition and displacement incidents, and in settlement-related construction.

- CAGE Judicial Review (September 2021): In September 2021, Al-Haq provided a supporting legal opinion, on whether any State can claim a “right” to exist under international law, for a judicial review case High Court Challenge in the United Kingdom. In particular, Al-Haq argued that the notion of Israel’s “right to exist” is a partisan political view that the Education Secretary is prohibited from promoting in any way under the 1996 Education Act.

- Prosecutor v HeidlebergCement: In August 2021, Al-Haq along with Guernica37 and Global Echo filed a petition to the German Prosecutor on the complicity of corporate agents in the case of HeidlebergCement. The filing followed a number of years research on the company including the publication of a comprehensive report Violations Set in Stone and submissions to the UN Database on businesses active in the Israeli settlements, UN Special Procedures, and exchange at the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre.

- Attorney General of Canada v. R. David Kattenburg and Psagot Winery Ltd. (May 2021): In March 2017, Jewish-Canadian human rights activist Dr. David Kattenburg filed a complaint with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) claiming it was inappropriate for wines produced in illegal Israeli settlements to be labelled “Product of Israel”. The CFIA initially agreed, but then reversed its decision and continued to allow such labels, citing the Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement (CIFTA)’s definition of Israeli “territory,” which includes areas where Israel’s custom laws apply, such as settlements in the OPT.This case is an appeal of a judicial review, of an administrative decision by the CFIA’s Complaints and Appeals Office (CAO), on labelling. The Appeal took place in Canada, and after decision was reverted back to the administrative body. Al-Haq filed to submit a joint legal amicus and submitted field research to the lawyers for the petition.

- CERD Inter State Complaint, State of Palestine v Israel (11 April 2021): Al-Haq drafted an amicus submission signed onto by the Palestinian Human Rights Organisations Council (PHROC), which was submitted to the Inter State Complaint to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, between the State of Palestine and Israel under the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

- Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 32 others (December 2020). Al-Haq contributed research from the Climate Change Adaptation under Occupation: Climate Change Vulnerability in the Occupied Palestinian Territory which was referenced as authority in the ESCR.net amicus submission. Al-Haq carried out joint work on the amicus in a climate change case against Portugal at the European Court of Human Rights.

- Al-Haq sent a formal complaint to the Dutch National Public Prosecutor’s Office in Rotterdam, the Netherlands in 2010 against a Dutch company, Riwal, involved in war crimes and crimes against humanity.19 The complaint that was submitted against Riwal was the result of the culmination of months of investigations and evidence-gathering by Al-Haq and partner organisations. Witness statements from those directly affected by Riwal’s activities were taken. The military orders used to appropriate land for the building of the Wall, aerial photographs, maps, film footage and photographs of Riwal’s activities were also collected. On 13 October 2010, the Dutch National Crime Squad conducted a search of Riwal’s offices in the Dutch town of Dordrecht under their statutory powers of investigation.

- R (Saleh Hasab) v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry (2007): Al-Haq, as a partner, took part in the case of R (Saleh Hasab) v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry at the UK High Court of Justice in London in 2007, United Kingdom.20 A full public hearing was held before the UK High Court of Justice in London on 10 -11 October 2007 following the blanket refusal by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry to respond to the claimant’s request for a justification of UK policy on arms-related sales to Israel. The High Court heard arguments in a claim filed on 15 November 2006 by UK Solicitor Phil Shiner of Public Interest Lawyers (PIL), in cooperation with Al-Haq.

Refer to Al-Haq’s website for a full list of Al-Haq’s activities, engagements, and submissions.

Forensic Architecture have produced evidence for the then-UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism Ben Emmerson QC, in whose company we presented our findings on drone warfare at the UN General Assembly in New York in October 2013 and the Human Rights Council in Geneva in 2014.

We presented evidence in the Israeli High Court in the case of The Committee of the Village of Battir vs. the Ministry of Defence (HCJ 7612/12) through Michael Sfard, who won this case on 4 January 2015.

Our report on the Use of White Phosphorus in Urban Environments was presented at the UN Human Rights Council Geneva in November 2012, and in March 2011 in the Israeli High Court through Michael Sfard.

Our Forensic Oceanography team presented the case of the Left to Die Boat before the French Tribunal de Grand Instance in April 2012, the Brussels Tribunal de première instance in November 2013, and in the courts of Spain and Italy in June 2013. Forensic Oceanography also had findings presented before the European Court of Human Rights in 2018.

The Gaza Platform and our Rafah: Black Friday report about the 2014 Gaza War, developed with Amnesty International, were submitted to the UN Independent Commission of Inquiry in March 2015, and to the International Criminal Court in March and September 2015.

Our 2019 investigation into the killing of Tahir Elci, a renowned Kurdish human rights lawyer, was cited by UN rapporteurs as instrumental in the re-opening of the Turkish state’s investigation into the killing, and was subsequently cited in the prosecutors’ indictment, and discussed at length in court.

Our investigation of the murder of Pavlos Fyssas was played before the Court of Appeal of Athens in 2018, as part of the trial of 69 members of the Golden Dawn political organisation, and was reportedly significant in the judge’s decision in the case.

Our investigation into the presence of Russian military units in eastern Ukraine in 2014 was submitted to the European Court of Human Rights in 2019 as part of an ongoing case.

Our investigation into intentional fire-setting in Papuan rainforests is currently before a court in Hamburg, where submissions were made in February 2021.

More information on our casework at www.forensic-architecture.org

Notes

1. ‘Marksmen’ in the Israeli army are different from ‘snipers’. Unlike snipers, they are part of a standard fighting squad: their task is to target shots more accurately than regular troops. They are differentiated by the use of different munitions (marked by green tips) and by their guns having a bio-pod and an optical scope (such as Trijicon ACOG x4). See here.↩

2. See Al-Jazeera’s report from 2 July 2022, here.↩

6. See here for IDF soldiers’ forum confirming marksmen’s equipment as that of Trijicon scope with 4x magnification; see here for the way in which M4 Carbine rifles are equipped; and here for Trijicon ACOG series.↩

8. When referring to spatial reconstruction at the level of ‘incident’, we refer to the methodological term created and employed by Forensic Architecture specifically, rather than the incident which is the focus of this investigation, as defined in section 3.↩

9. A ‘cone of vision’ refers to the area visible and is represented by a cone where the point originates at the eye, and where the angle of the cone reflects the optical properties of a human eye.↩

15. By significant moments, we mean the moment when the journalists were walking towards the IDF’s position, identifying themselves as journalists (06:31:06); the moment when the IDF fired the first round at the journalists (06:31:07); the moment the second round of shooting began, and we last see Shireen alive (06:31:18); and after Shireen as been shot and is seen lying on the ground (06:31:37).↩

16. We call this ‘situated testimony’.↩

17. See here for UNESCO and Reporters Without Borders guidelines. ↩

![Digital reconstruction of shooter’s view - Digital reconstruction of the visibility of the journalists as they were walking up the road. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)](https://content.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Digital-reconstruction-of-shooters-view_HiRes-2400x1350.png)

![Optical reconstruction of shooter’s view_Shireen - On site visual reconstruction of Shireen's visibility the moment she was shot. As would be seen through the Trij[icon] ACOG 4x32 BAC riflescope. (Forensic Architecture and Al-Haq, 2022)](https://content.forensic-architecture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Optical-reconstruction-of-shooters-view_Shireen_HiRes-2400x1350.png)