Commissioned By

- Lawyers for the Duggan family

Additional Funding

Collaborators

- Bhatt Murphy Solicitors

- Birnberg Peirce

- Tottenham Rights (formerly the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign)

- The Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA)

Methodologies

Forums

View the interactive feature on the Guardian here.

Click here to explore the scene in a virtual reality 360° video.

Read about our investigation in depth in our methodology report.

Read our letter to the Independent Office of Police Conduct.

The shooting

On 4 August 2011, Mark Duggan was shot to death by police in Tottenham, north London, after undercover officers forced the minicab in which he was travelling to pull over.

As the vehicle came to a stop, Duggan opened the rear door, and leapt out. Within seconds, an advancing officer known only by his codename, V53, had fired twice. The first shot passed through Duggan’s arm, and struck a second officer, known as W42, in his underarm radio. The second, fatal shot hit Duggan in his chest.

V53 would later tell investigators that he saw a gun in Duggan’s hand, and felt his life to be in danger. Duggan was being monitored by Operation Trident, a controversial unit of the Metropolitan Police focused on gun crime in London’s Black communities; firearms officers had followed him from a nearby meeting, at which he had reportedly collected a gun. But following the shooting, the gun in question was found around seven metres away from where Duggan had been shot, on a nearby patch of grass. But no officers reported that they saw Duggan throw the gun, or make any kind of throwing motion.

That question – how did the gun get to the grass? – remains at the heart of the Duggan case.

There are only three possibilities: either Duggan threw the gun before he was shot, or while he was shot, or it was moved to the grass after the shooting, by one or more of the officers involved.

The aftermath

In the hours following Duggan’s death, multiple news reports falsely described an incident in which an individual had opened fire, injuring an officer. The Daily Mail called Duggan a ‘gangsta’, while the Guardian reported an ‘exchange of fire’. However, it became clear soon afterwards that W42’s injuries had been caused by another officer; a week later, investigators would admit that they may have ‘verbally misled’ journalists in the hours after the killing.

By 6 August, two days after his death, Duggan’s family had still not been formally contacted by the Metropolitan Police. They led a protest march to Tottenham Police Station.

When police continued to refuse to meet with the Duggan family, the protest became confrontational, eventually growing into the most widespread social unrest seen in the UK in a generation—what became known as the London riots, but which spread to towns and cities across the country. In the days that followed, five people lost their lives, and over three thousand were arrested, resulting in almost two thousand years of prison sentences.

The inquest and the IPCC

Following the killing, the UK’s national police watchdog, then known as the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), took immediate charge of the investigation. IPCC investigators arrived on the scene within hours. The interviews carried out by the IPCC, as well as many of the expert reports they commissioned, would form the evidentiary basis for a 2013 coroner’s inquest, which would also commission additional expertise, and interview dozens of witnesses.

In 2014, the inquest jury concluded that V53’s actions constituted a ‘lawful killing’. This conclusion was reached despite majority agreement among the jury that Duggan had not been holding a gun at the time he was shot; eight out of ten believed Duggan had thrown the gun immediately before exiting the minicab. Crucially, a verdict of ‘lawful killing’ only requires that V53 believed Duggan to be holding a gun at the time of the shots.

The inquest had not proceeded straightforwardly. A controversial piece of legislation known as the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, or RIPA, prohibited the public disclosure of potentially vital information gained from police wiretaps, and almost prevented the inquest from going ahead at all.

While the family were devastated by the jury’s finding, the judge overseeing the inquest, Justice Cutler, penned a remarkable report in which he raised eight ‘concerns’ about procedural failings in the investigation of the incident, as well as the RIPA-mandated withholding of intelligence from investigators and lawyers.

The IPCC’s investigation, in Justice Cutler’s view, was under-resourced and poorly managed. Investigators failed to gather ‘comprehensive’ statements from witnesses, he wrote, allowing the officers involved in the shooting to submit ‘bland and uninformative’ witness statements. He concluded: ‘I was left with an impression of some uncertainty about precisely what was being investigated, on whose behalf, for what purpose, and by what means.’

A year later, the IPCC published its own, long-delayed final report. It made a total of twenty-four findings, among which it concluded that the ‘most plausible’ explanation for the location of the gun was that Duggan had been ‘in the process’ of throwing it as he was shot.

FA’s investigation

FA was commissioned by the Duggan family’s lawyers to reconstruct the scene of his death as a navigable digital environment and, within that environment, to illustrate and interrogate the testimonies of the officers involved in the shooting.

FA examined videos and images, witness testimony, hand-drawn plans, and reports, including material originally commissioned by the IPCC and by the inquest, as well as new expert biomechanical report commissioned by the family’s lawyers. Bringing that information together, we reconstructed the sequence of events in an animated virtual reality (VR) environment (explore it here), within which our researchers could view the sequence of the ‘hard stop’ and the subsequent shooting in real time, from the perspective of multiple officers.

Using these tools, FA examined three possible answers to the critical question: how did the gun get to the grass?

Duggan's movements during the period of the shots

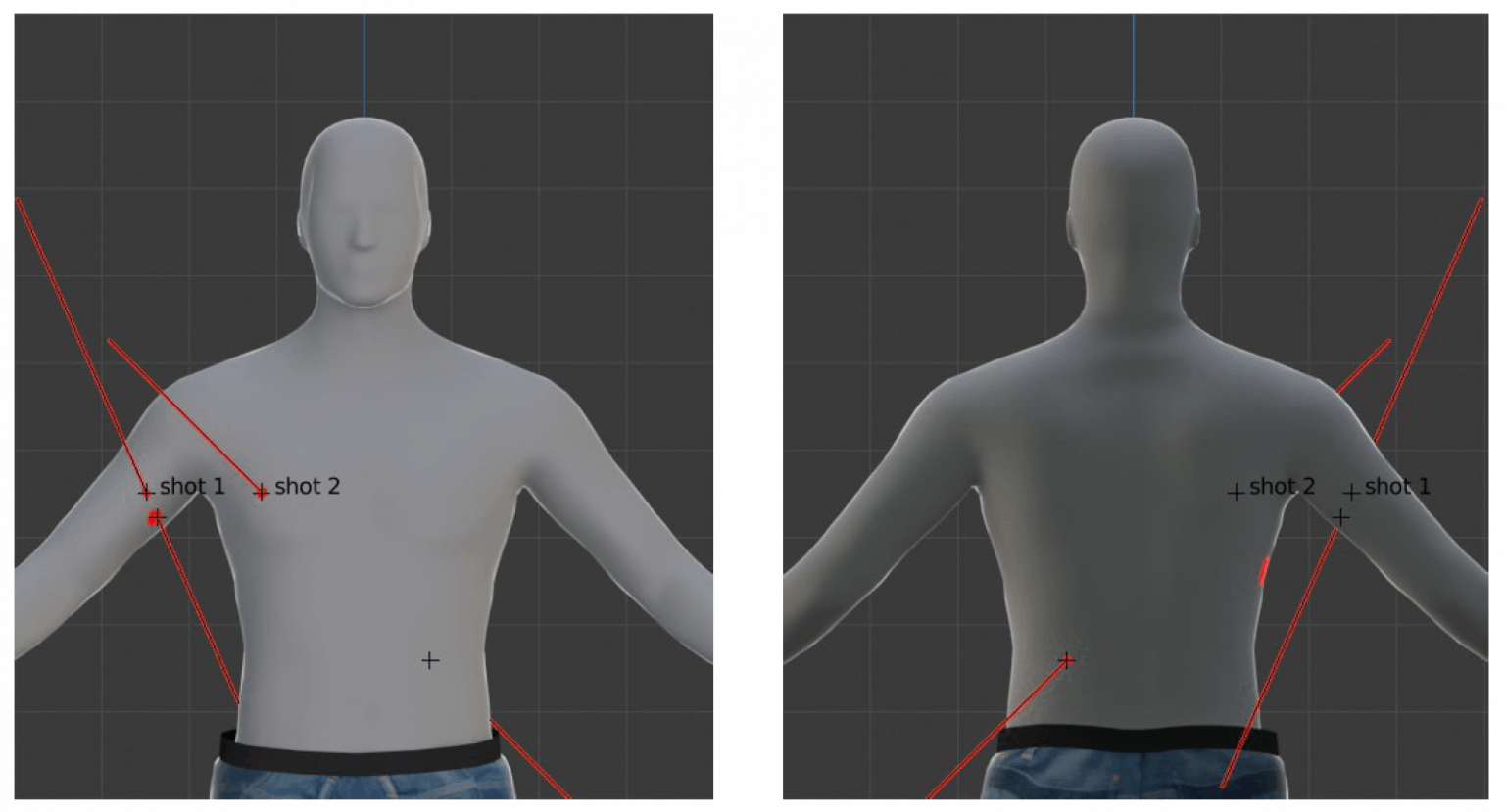

Pathology reports describe precisely the location of the injuries sustained by Duggan: one bullet passed through Duggan’s right bicep, also causing damage to the right hand side of his chest wall, while another passed through his torso, entering in the upper right hand side of his chest, and exiting through the lower left hand side of his back.

Lines drawn between each entry and exit wound pair, and extrapolated beyond the body, describe the direction of travel of each bullet in relation to Duggan’s body. These ‘shot lines’ give us an indication of his body position at the time of each of the shots, as well as information about the locations of officers V53 and W42 relative to Duggan.

That and other information, including damage to Duggan’s jacket, the height of each of the officers, and of Duggan, and the dimensions of the open rear door of the minicab, helped us to place Duggan, V53, and W42 precisely in relation to one another, and the minicab.

From here, we could examine in detail the conclusion of the IPCC: that Duggan had thrown the gun during the period in which he was shot.

'Duggan threw the gun during the period of the shots'

This was the conclusion that was arrived at by the IPCC: that ‘the most plausible explanation for the location of the gun is that Mr Duggan was in the process of throwing the gun as he was shot’.

The gun was found seven metres from where Duggan was located at the time he was shot. Biomechanics experts told us that to throw the gun that far would require a large, sweeping motion with Duggan’s right hand.

Could V53 have missed such a motion? And, after he was shot, would Duggan have been physically capable of making such a throw?

V53 was standing around three metres away from Duggan at the time of the first shot. It was around 6pm, on a clear August afternoon. What would the throw look like from V53’s perspective? Within our model, we could begin to approximate an answer.

Since human vision differs from how images appear on a computer screen, we built a virtual reality (VR) environment to more closely approximate what the officers involved could have experienced. You can explore that VR environment yourself, below.

We cannot experience precisely what V53 experienced at that moment, which makes it difficult to conclusively challenge the officer’s report of his own experience. (This is part of the explanation, perhaps, for the verdict of ‘lawful killing’ given by the inquest jury; it is an example of the logic of the ‘split second’, by which the right of police officers to carry out violence against civilians is enshrined and protected.)

However, it is worth noting that V53 claimed to be looking directly at Duggan, and specifically at the gun he said he saw in Duggan’s hand, at the moment immediately before the shots, and again, at the moment between the first and second shot. You can read his testimony to the inquest here.

The forensic pathologist Professor Derrick Pounder, originally commissioned by the IPCC for their investigation and then again by the lawyers for the Duggan family, stated in 2019: ‘I cannot conceive of how Mr Duggan might have thrown the gun to the place it was found, unobserved by the police.’

According to the IPCC, the officer’s failure to notice the gun being thrown ‘does not undermine V53’s account’. According to our analysis, however, the IPCC’s conclusion is not consistent with the available spatial and biomechanical evidence.

'Duggan threw the gun from the minicab'

If Duggan threw the gun to where it was found, but he did not do so during the period in which he was shot, he must have thrown it immediately as he exited the minicab. (The rear windows of the minicab, a Toyota Previa, did not open fully, so he could not have thrown it before the door was open. The minicab driver and V53 both testified that the rear nearside door of the minicab was opened as soon as the vehicle came to a stop.)

This was the conclusion of the inquest jury: that ‘more likely than not, Mark Duggan threw the firearm as soon as the minicab came to a stop.’ The available evidence does not rule out this scenario; however, would the gun have passed through the field of vision of any of the officers, if it was thrown?

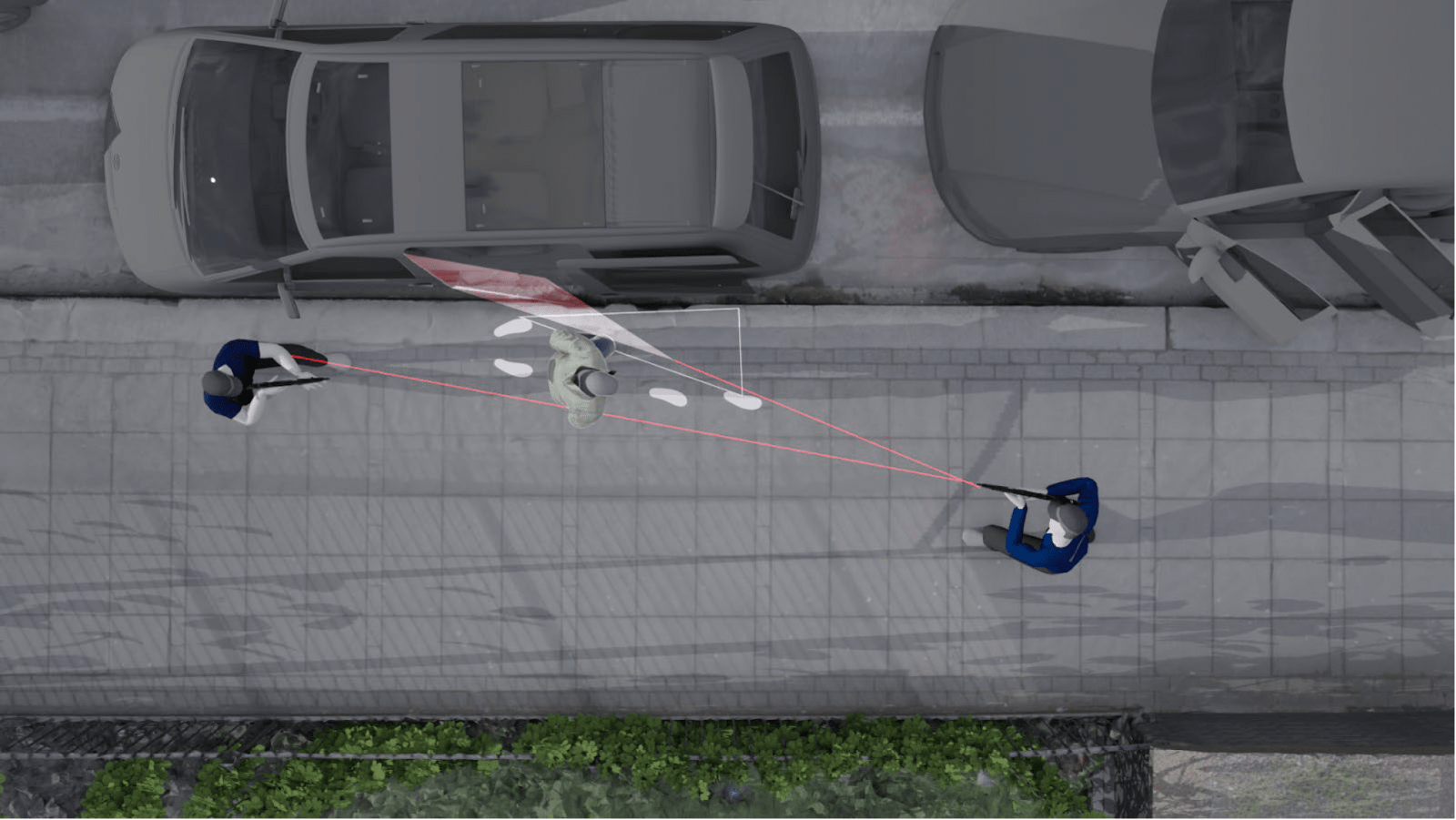

We identified four officers who, from what is known of their locations from their testimony and other evidence, would have been in a position such that the gun could have crossed their field of vision. While we cannot equate ‘passing through their field of vision’ with ‘being perceived by those officers’, the verdict of the inquest jury does require that not just one, but at least four officers failed to notice the gun being thrown. See two of their perspectives in VR, below.

With every additional officer who missed it, this scenario becomes less likely. This makes it even more important to consider the final possibility: that officers moved the gun after Duggan was shot.

'The gun was moved by police officers'

The aftermath of the shooting was filmed from the ninth floor of a nearby building, by a member of the public known as Witness B. They begin filming around 40 seconds after Duggan was shot, and continued for 15 minutes. The footage is shaky, and low-resolution. Based on this footage, the IPCC made two claims: first, that ‘there is no sign of any officer planting a firearm on the grass’, and second, that ‘there is no evidence any person entered the rear of the minicab’.

However, these statements are misleading. Concerning the first claim, we demonstrated that the footage is of such low resolution that, in fact, an object the size of the gun reportedly found on the grass would not be visible in the footage at that distance.

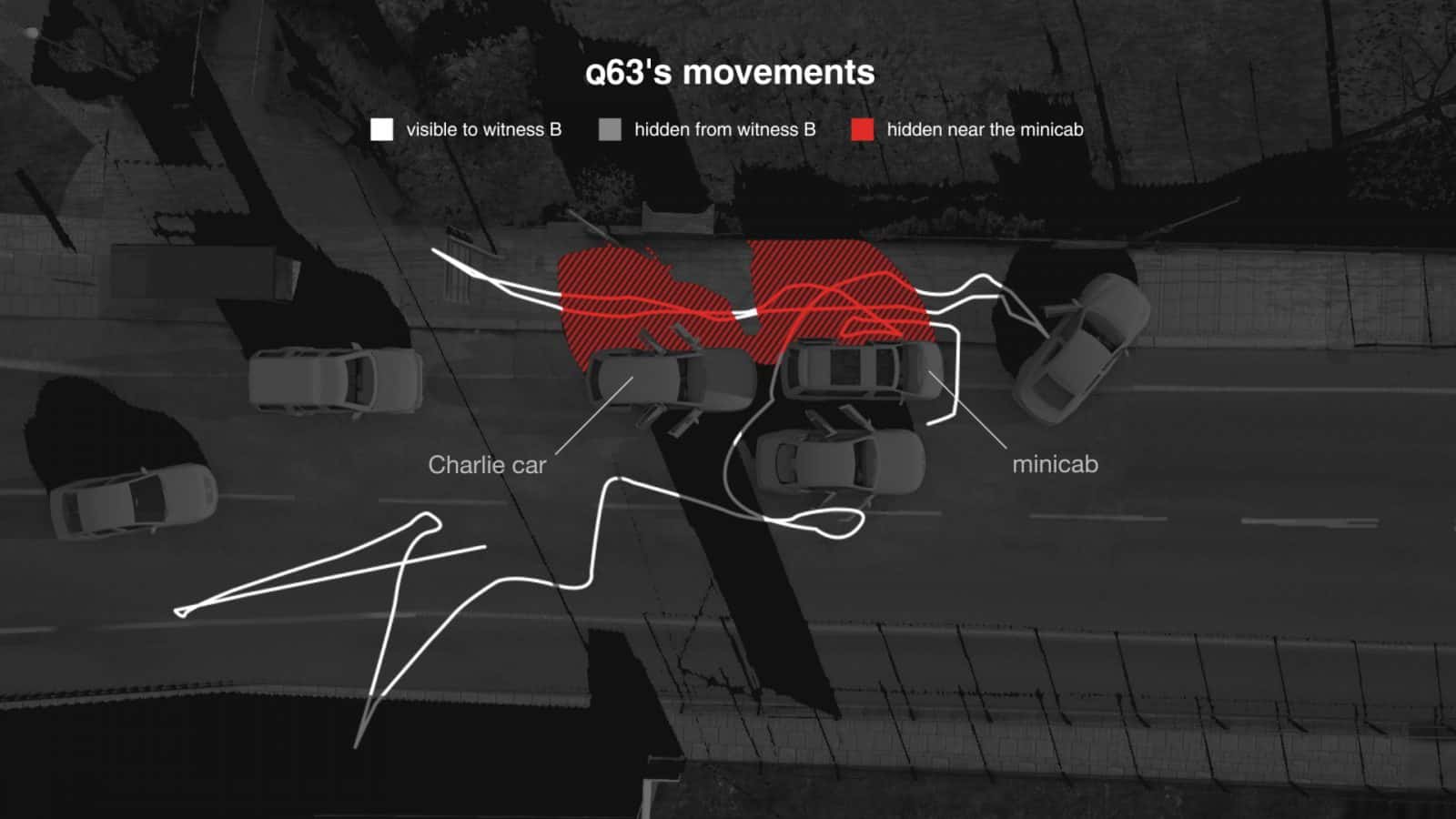

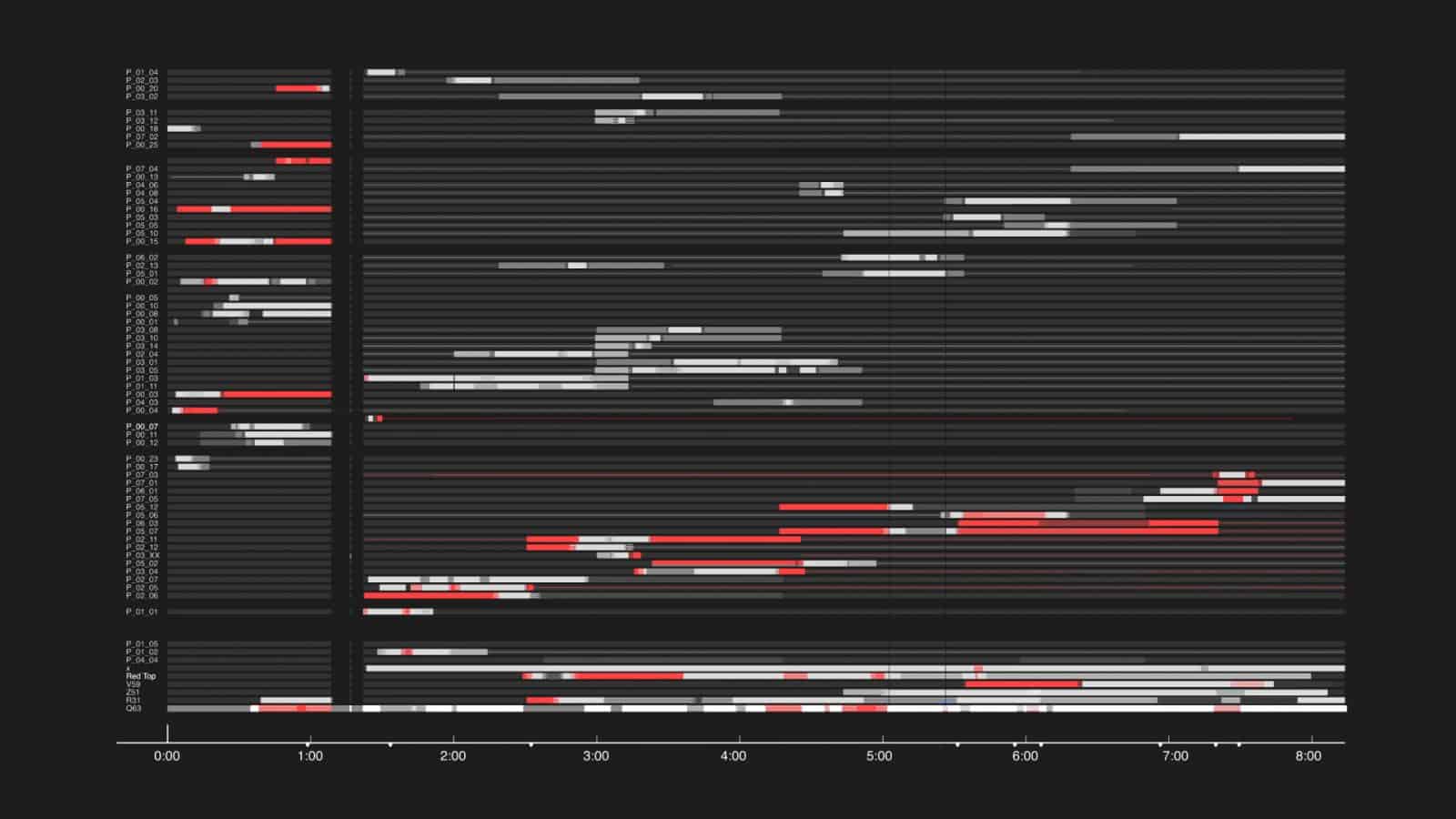

We are able to make out the figures of various officers as they move around the scene. Through a painstaking process of analysis, tracking, and cross-referencing, we identified many of the officers, and identified more than a dozen moments when they disappeared behind the minicab and Charlie car – highlighted in red on the timeline below.

This process meant that we could see when any officer was partly or fully hidden behind the minicab and a nearby police vehicle, codenamed Charlie car. In total, officers entered this zone more than a dozen times. But the IPCC did not examine these moments in any detail.

These moments don’t tell us that the gun was moved by police officers. However they do show that, based on the footage alone, the IPCC has no grounds to rule out the possibility that any officers entered the rear of the minicab.

Using this tracking process, we were also able to identify series of ‘chains of connection’ which could, hypothetically, have constituted a route for the gun to be carried from the minicab to the grass. While these do not demonstrate that the gun was moved by officers, it demonstrates that the IPCC cannot use the footage to easily rule out that possibility.

Public presentation

In November 2019, we presented our findings publicly for the first time in Tottenham, less than a mile from where Duggan was killed, at a community event hosted by Stafford Scott, founder of Tottenham Rights (formerly the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign). Watch it below, in three parts:

Update

26.05.2021

26.05.2021

After more than a year of deliberations, the IOPC declined to re-open the investigation into Duggan’s death. The IOPC’s justification for that decision misrepresented or ignored crucial parts of our findings, and of other expert evidence.

You can see below the correspondence between FA, a legal firm representing the Duggan family, and the IOPC:

– February 2020: FA writes to the IOPC

– December 2020: IOPC invites FA to submit further information

– January 2021: Birnberg Peirce writes to the IOPC

– April 2021: FA writes to IOPC inquiring about a decision

– May 2021: Final decision by the IOPC

And here, you can read our public statement in response to the IOPC’s conclusion, which was also reported on in the Guardian and the Daily Mirror.

Update

06.07.2021

06.07.2021

War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truth and Rights, a new exhibition curated by Tottenham Rights and featuring our work on the Duggan case, opens at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art.

Methodology

Methodology

Virtual Reality (VR)

Our investigation of Duggan’s killing turned on the question of what different police officers saw or could have seen as the incident unfolded. Which officers had a direct line of sight to Duggan when he was shot? What would V53 have seen as he approached Duggan, and could he have missed the throwing motion that Duggan would have had to make, in order for the gun to reach the location in which it was found?

To engage with these and other questions, and to mitigate the difficulty of representing human vision through a flat screen, FA developed a virtual reality (VR) environment from our digital model. With a VR headset, we could view the animated sequence of the ‘hard stop’, and the subsequent shooting, in ‘real time’, and in as close to realistic vision as possible.

Now you can too: below, experience the ‘hard stop’, and the events that followed, from two the perspective of the two officers most closely involved in the shooting, as well as from vantage points on either side of Ferry Lane.

You can view 360° videos on a computer, a mobile device, and with or without a VR headset. On a laptop, use your mouse or trackpad to look around. On mobile, you simply tilt and move your device to explore. You can also move through a 360° video by dragging your finger across the screen. To view on a VR headset, download the Vimeo app (Android/Apple).

V53

V53, the officer directly responsible for Duggan’s death, claimed that, while he could see a gun in Duggan’s hand, he saw no kind of throwing motion, and that he does not know how the gun that he claimed to see in Duggan’s hand travelled to where it was found.

Below, experience V53’s perspective within our animated model, in one of four scenarios: without Duggan holding or throwing a gun, and with Duggan throwing the firearm before, during, and after the two shots:

W42

The officer known as W42 approached Duggan from the opposite side of the minicab to V53. The first shot fired by V53 hit W42 in his underarm radio.

Below, experience W42’s perspective in three scenarios: without Duggan holding or throwing a gun, and with Duggan throwing the gun before and after the first shot.

Throw from the minicab

In 2014, an inquest jury concluded that Duggan had more likely than not thrown the gun before or as he exited the minicab. According to our spatial analysis, and analysis of witness testimony and other evidence, at least four officers would have been in a position such that the gun, if thrown from the minicab, could have crossed their field of vision.

Below, experience what W42 and V53 could have seen, if Duggan had thrown the gun from the minicab.

Scene view

For a fuller account of the incident, you can also view below the sequence of the ‘hard stop’ from two additional ‘floating’ positions on the Ferry Lane pavement next to where Duggan was shot, in the same series of scenarios.

Scene view (east)

When looking at a 3D perspectival image rendered on a computer screen, the viewer is forced to see it with a fixed Field of View (FOV) defined by the angular setting of a given software’s virtual ‘camera’. A wide FOV will allow the viewer to see a large portion of the scene and a narrow FOV will allow the viewer to see a small portion of the scene. All parts of this field of vision are rendered at the same resolution and level of detail.

Human vision has a wide FOV, spanning approximately 150° horizontally, and 120° vertically. But that visual field is not homogenous: only about 5° of the visual field—the area the eye is trained on—is sufficiently sensitive to register precise or fine-grained details. By contrast, the marginal areas of the visual field are particularly sensitive to movement. Unlike on screen a VR environment allows for a realistic relation between the wearer fields of vision and the dynamic scene being modelled. VR does not require a fixed FOV, but utilises the visual field of the user, providing a natural sense of vision in relation to moving bodies and objects, and allowing for intuitive spatial interaction with the scene.

While a rendered model view is useful in interrogating the perspective of participants in incidents, a VR simulated environment is more precise and useful a tool.

Read more on our methodology in our methodology report.