Date of Incident

Location

Publication Date

In Partnership With

- The Guardian

- Earthjustice

- Healthy Gulf

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade

- The Descendants Project

- Boundless Community Action

Additional Funding

Collaborators

Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

—Read our methodology report

—Read the Guardian feature, The huge US toxic fire shrouded in secrecy: ‘I taste oil in my mouth’

Marathon Petroleum Corporation’s facility in Garyville, Louisiana, is one of the largest refineries in the western hemisphere. Nearby residents of ‘fenceline’ communities, which directly border this and other facilities across Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley’,1 are forced to breathe some of the most toxic air in the US; the cancer risk for local residents is seven times the U.S. national average.

On 24 August 2023, a tank at the Marathon facility containing naphtha—a volatile hydrocarbon chemical mixture—began leaking, and 3.76 million kg (8.3 million lbs) of toxic flammable material was released, amounting to the second largest chemical spill in thirty years, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).2

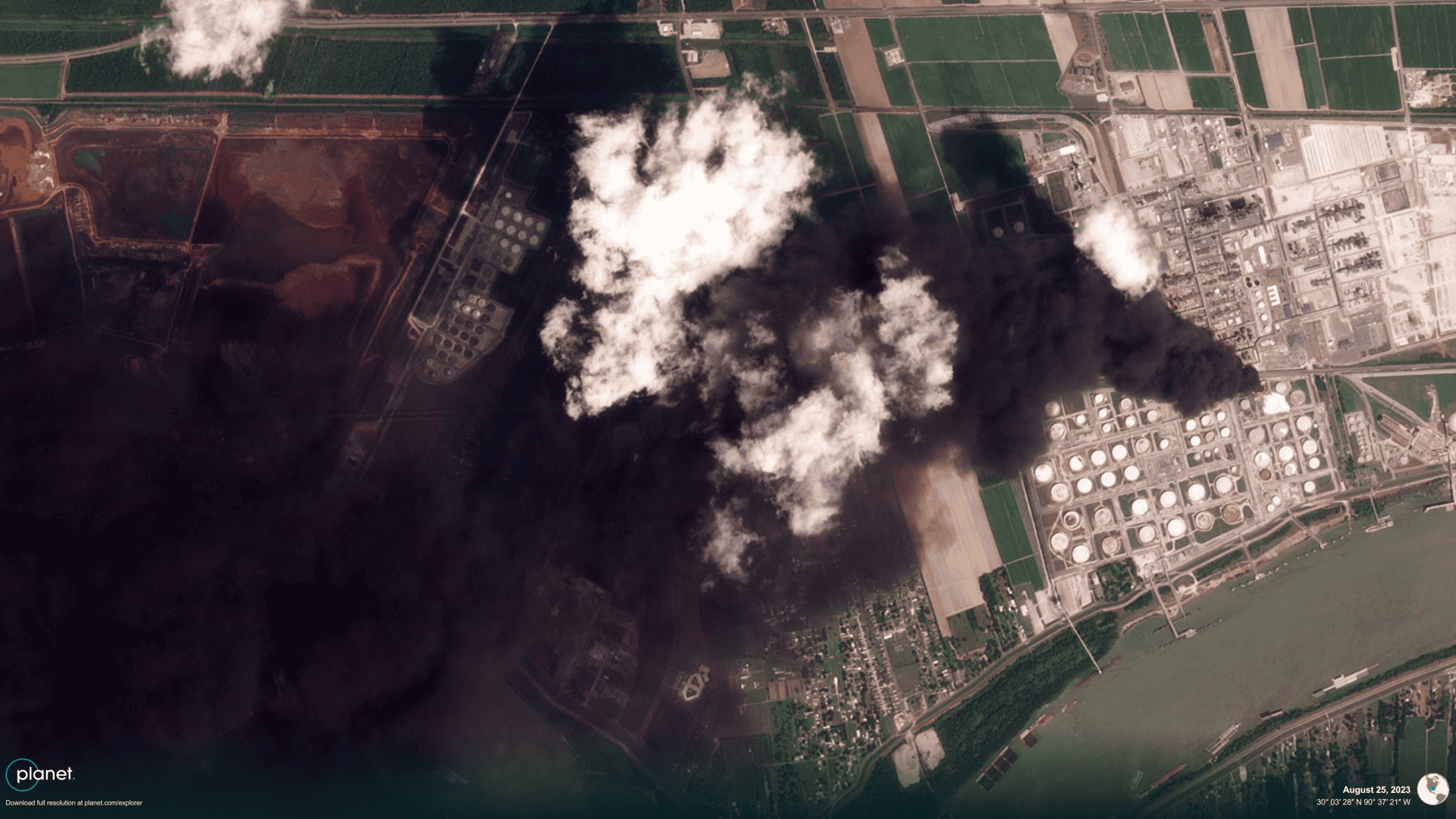

For two days, residents of nearby communities and local reporters documented the growth and movement of a thick, black chemical plume; satellite images showed it stretching over 96km (60 miles). Yet even as residents reported severe health impacts, including several hospitalisations, state and corporate officials consistently claimed that there were no impacts beyond Marathon’s property line.

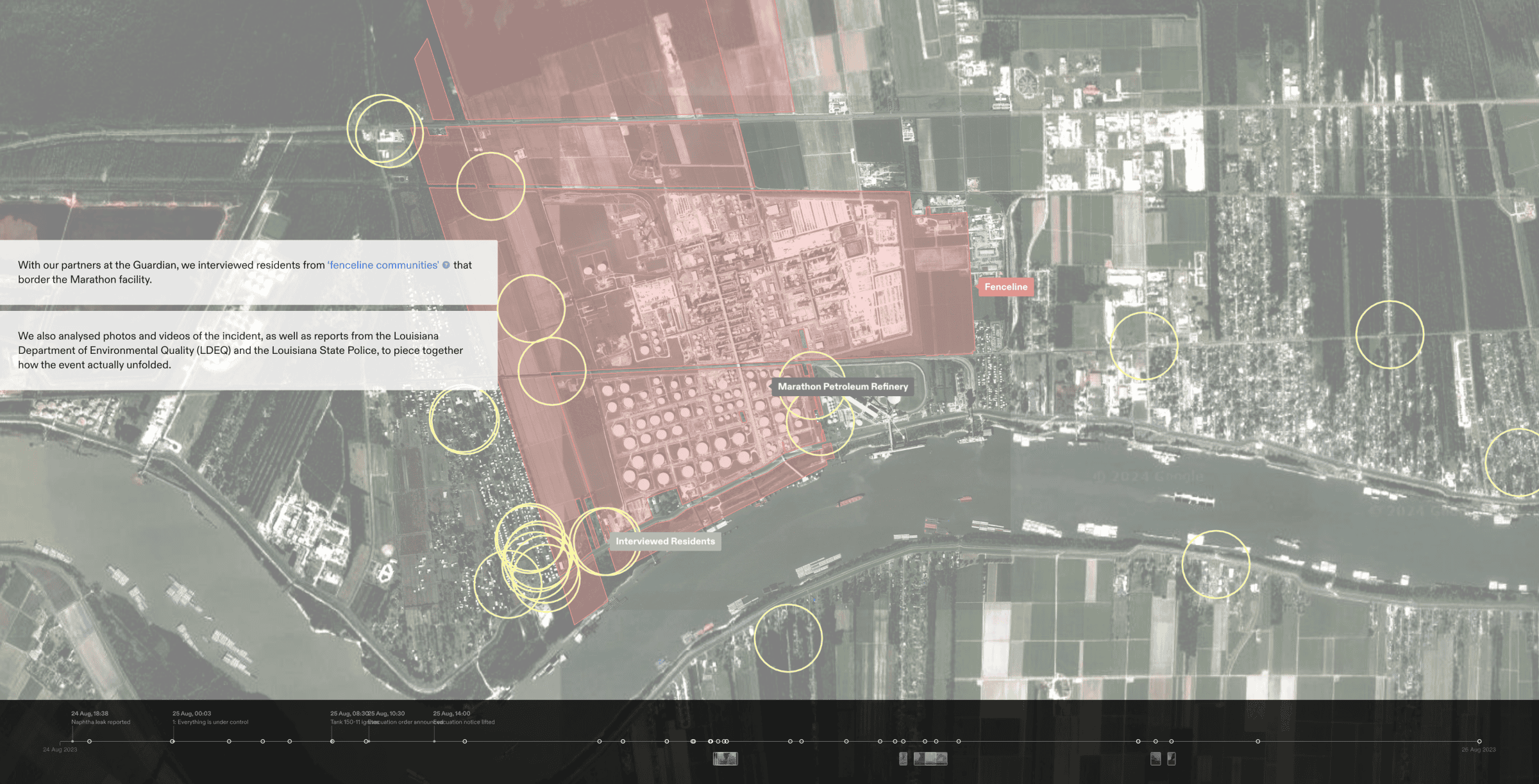

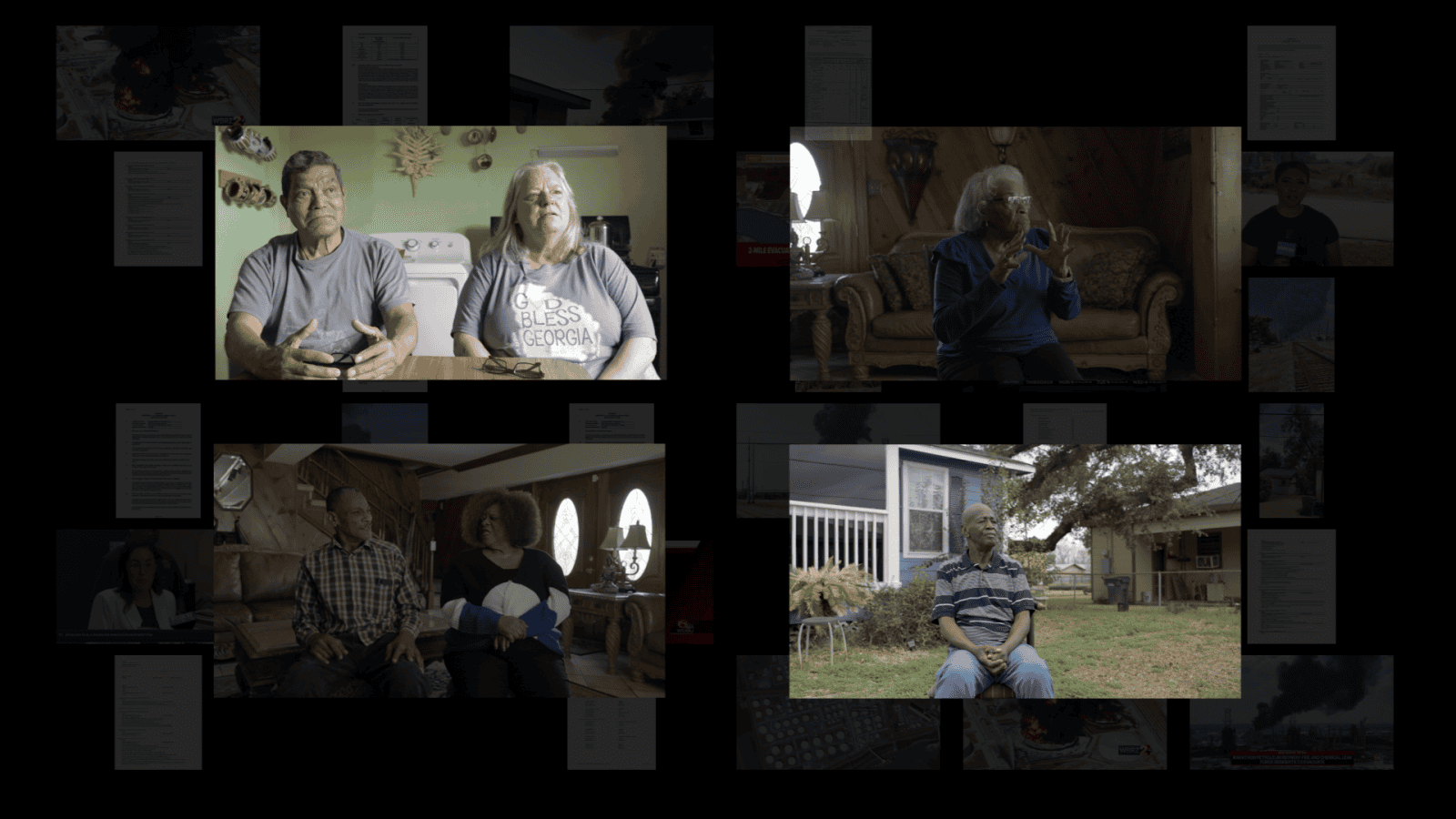

With the Guardian, we interviewed seventeen residents of the fenceline communities that border Marathon’s property. Drawing from these testimonies and a wide range of open source materials, we constructed a 3D model of the refinery site and smoke plume. We also worked with collaborators at Imperial College London to develop a fluid dynamics simulation of the plume and its chemical components, mapping their movement and density within our model to evaluate the potential health impacts of the incident.

To make visible the inconsistencies and gaps in authorities’ reporting, these different elements were then incorporated into a narrative platform designed to track and compare evidence of the incident’s development, accounts from residents, and the state’s response over time.

Background

The Marathon Garyville Refinery is located at the heart of an 85-mile stretch of Louisiana’s Mississippi River, known as ‘Cancer Alley’, or ‘Death Alley’—referring to the fact that the region has the highest risk of cancer and other serious health ailments in the U.S. Historically, this region was known as ‘Plantation Country’; today, over two hundred of the nation’s most polluting petrochemical facilities occupy the fallow footprints of formerly slave-powered sugarcane plantations. The latest incident at the Marathon facility can be understood not as an isolated incident, but rather as an acute eruption of a chronic condition of environmental racism that has plagued the region for three hundred years.

In 2021, FA was commissioned by local community activist groups Rise St. James and the Descendants Project to investigate the construction of industrial facilities atop unmarked Black cemeteries. This investigation into the Marathon fire continues FA’s commitment to supporting the multigenerational struggle of Cancer Alley’s fenceline communities.

‘No offsite impacts’

A joint statement by the St John the Baptist Parish President and a Marathon Petroleum Corporation representative, made during a live, televised press conference at 10:30am on 25 August, claimed that ‘any impacts have been contained to the Marathon site’. Our investigation sought to understand how that day’s events unfolded, to test that claim and to scrutinise the response of authorities during the incident and its aftermath.

The interviews undertaken with residents from more than a dozen of the fenceline communities surrounding the Marathon refinery shared a number of common refrains. Many described feeling abandoned over the course of the incident, and found the communication from state officials and Marathon representatives unclear and even contradictory at times. Some underscored that their inquiries to emergency services about evacuation had been met with inconsistent and vague responses, which corresponded with the fact that an official evacuation order was announced long after the incident began, and lifted well before the incident was over.

Olfactory testimony

Despite officials’ assurance that the naphtha leak and resulting fire were ‘contained’, local residents reported a strong chemical smell resembling ‘burning oil’ or ‘burning plastic’ over the course of the incident, beginning in the early hours of 25 August. This chemical smell entered homes through air conditioning units, and lingered for days, even after the fire was finally extinguished.

According to Dr Salvador Navarro-Martinez, an expert in fluid dynamics at Imperial College London, smell is often the earliest indication of chemical exposure. Residents’ descriptions of resulting symptoms are also consistent with chemical exposure, including respiratory distress, burning eyes, and sore throats. Several individuals sought medical attention, and three were admitted to the hospital.

Building an incident timeline

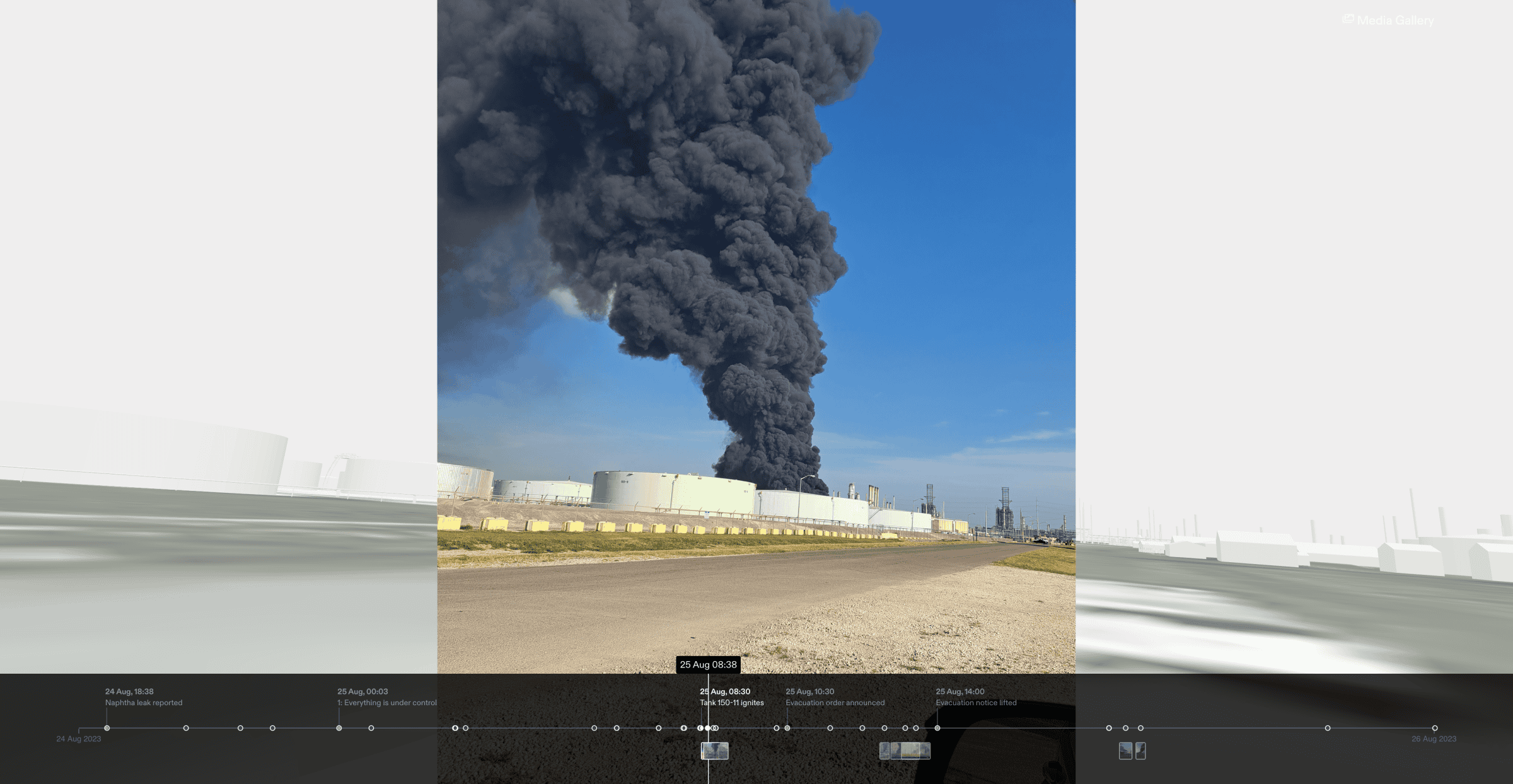

We developed a digital 3D environment, within which we situated residents’ testimonies, and a digital reconstruction of the chemical plume extrapolated from images and videos of the incident captured by local residents and media. Together, these elements allowed us to form a timeline of the event.

Analysing the images for location information, as well as data such as shadow length and direction, helped us determine the precise time that they were captured and place them accurately within both our timeline and modelled reconstruction of the Marathon facility and surrounding communities.

Our digital environment made it possible to use those same images to model the smoke plume as a 3D volume, and reproduce its movement and evolution over time, looking in particular at its position in relation to nearby communities at key moments throughout the incident.

Typically, the highest concentrations of dangerous pollutants, such as particulate matter, circulate in the shadow of the plume—the zone where the plume-as-object gives way to plume-as-atmosphere.

Fluid Dynamics Simulation

The plume’s movement is largely a function of local weather dynamics. On the first day of the fire, local news channel WWLTV broadcast weather radar data from between 10:10 and 11:13am, which roughly visualised the plume following the direction of the prevailing wind.

During this one hour, the prevailing wind blew primarily in a westerly direction, and so reporters cautioned their viewers that the greatest risk was to those communities to the west of the facility.This advice, however, was based on an incomplete assessment of the meteorological dynamics at play, and therefore of the degree of risk.

To provide a more complex and sustained analysis of the plume’s scale and movement, we worked with our partners from Imperial College London’s Department of Mechanical Engineering to create a 3D digital simulation of the plume. The simulation, which relied upon detailed and dynamical data from a weather station in Welcome, Louisiana, filled in the gaps between the images and videos of the plume captured from nearby communities, and made visible the plume’s invisible toxic components.

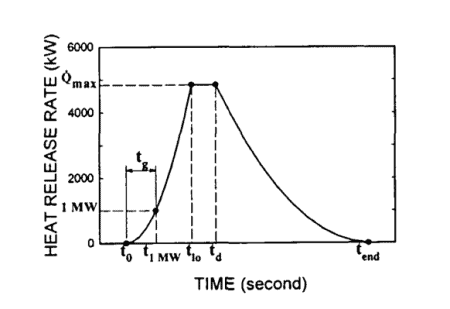

Drawing on data from Marathon’s reports, we used the following mathematical formula to model the burning of the tanks’ contents over the course of 22 hours:

It is important to note that the above graph is an idealised burn scenario; in actuality, the process of combustion at the Marathon facility would have been affected by firefighting efforts, as well as other local conditions.

Together with Dr Navarro-Martinez, we simulated the development of the smoke plume resulting from the ignition of naphtha in the containment area. In addition to simulating the smoke plume, we simulated the movement of two criteria and toxic air pollutants: particulate matter (PM 2.5) and benzene.

PM 2.5 is a particularly dangerous form of fine airborne particle, both odourless and invisible to the naked eye. Exposure to PM 2.5 has been linked to cardiovascular, neurological and respiratory impacts and is a likely human carcinogen. Even short-term exposure of up to 24 hours has been associated with premature mortality.

Benzene, meanwhile, is a human carcinogen. Short term exposure impacts the respiratory system, while long term exposure is linked to a significant increase in cancer risk, particularly leukaemia.

In our simulation, we represented the smoke plume as a transparent solid bounded by a yellow mesh. PM 2.5 was represented as a point cloud, where each visible point (rendered in yellow) represents 1 billion particles. Concentrations of benzene in the air at 20m above ground level are represented by a ‘colour ramp’ which is projected onto the terrain.

Our simulation showed that between 6:30am and 1:00pm, the plume made a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree rotation, blowing across at least four different communities.

In the early hours of the day, in keeping with the aforementioned weather reports, the wind blew in a westerly direction, over Garyville. Around 12pm, however, the wind shifted southwards over Edgard, before moving eastward, over Lions and Reserve, where it lingered for the rest of the day. According to our simulation, around 8:40pm on 25 August, residents of Lions were exposed to concentrations of benzene that reached 0.04ppm, more than four times the US Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) standard for acute exposure, which limits benzene exposure to 0.009ppm over a two-week period.3

The highest levels recorded in Lions by our simulation were 0.17ppm—more than 18 times the CDC’s standard for acute exposure. Due to the resolution and complicating factors of our simulation (see methodology report), even the highest concentrations recorded likely represent the conservative estimate, or lower limit, of exposure.

More than 635kg (1,400lb) of benzene—nearly 150 times the daily emissions limit for the entire state, according to EPA guidelines—were reportedly released over the course of the incident based on the figures submitted to LDEQ.

Acute incidents such as this one compound the effects of St John residents’ chronic exposure to regularly permitted carcinogenic emissions from the half-dozen facilities in their parish.

Underestimation of risks

We compared the sequence of events recorded in incident reports drafted by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) and the Louisiana State Police (LSP), as well as post-incident reports submitted by Marathon to LDEQ and the EPA.

Those reports indicate that a leak from Tank 150-11, which contained 67,770 barrels (9.2m litres) of naphtha, was first reported to LDEQ at 6:38pm on 24 August. Service along the industrial freight rail located less than 30m (100ft) from residential homes and 40m (135ft) from the tank was suspended between approximately 8:30pm and 10:30pm. Louisiana State Police arrived on the scene at 9:45pm, and LDEQ arrived shortly after 11pm.

By midnight on 25 August, the state police noted in their reportsthat ‘no further protective actions [were] necessary’, apart from continued air monitoring near the fenceline. They reported at the time that ‘the situation is under control and there is no expectations [sic] of it to change’.

In the early hours of the morning, within a few hours of this determination, quite a few of the local residents we spoke to began to smell a powerful chemical odour. According to their accounts, no state or corporate representatives contacted them about the ongoing incident.

By 6:31am, the incident began to escalate dramatically. The ground throughout the containment area in which Tank 150-11 sat, by now saturated with naphtha, had caught fire. According to multiple reports from residents, the facility’s emergency alarm, which is tested weekly, did not sound at this time or at any other time during the incident.

By 8:30am, Tank 150-11 was reportedly ‘engulfed in flames’. One minute later, the adjacent tank, 300-7, also ignited. The fire, reports noted, ‘was not under control’. Still, it would take another two hours for local officials to begin to evacuate residents from neighbouring communities.

Evacuation order

Around 10:00am on 25 August, local officials held a press conference, at which they announced an evacuation order for the immediate area surrounding the facility.

Some hours later, around 1:30pm, the fire briefly subsided, and as a result, at 2pm, the evacuation order was lifted. Some of the residents who had been able to evacuate returned to their homes in the hours following.

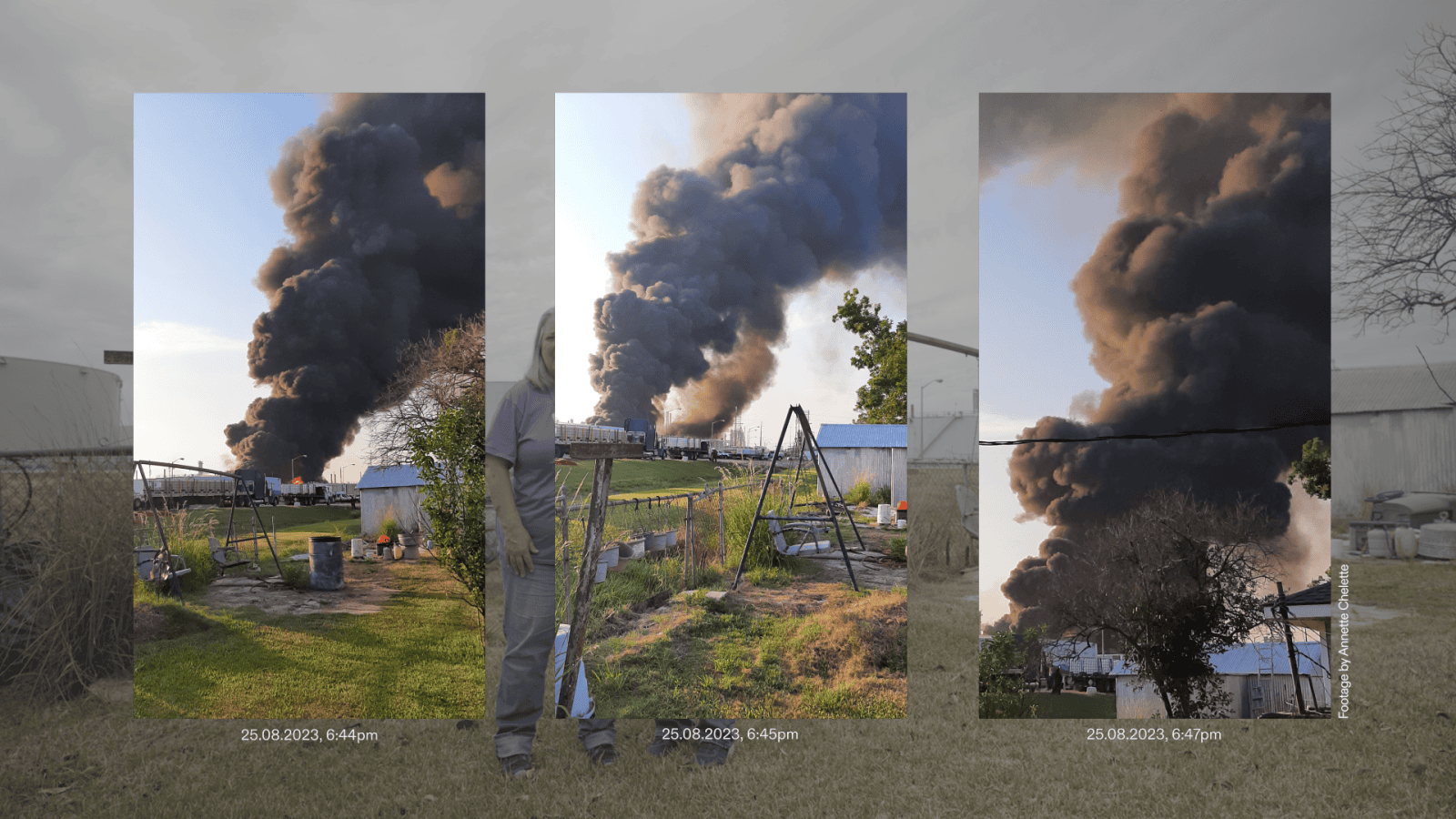

But within just a few hours of the order being lifted, the incident escalated once again. By 6:45pm, photographs taken by a local resident captured the fire blazing with renewed ferocity, accompanied by a towering smoke plume, a mere 400m (1,312 ft) from the resident’s backyard. That evening, according to our simulation, concentrations of benzene reached levels three times the CDC’s standards for acute exposure.

During the night of 25 August, residents who couldn’t afford to evacuate spent the night with air conditioners turned off, despite high temperatures—a learned strategy for reducing the entry of toxic fumes into private homes and businesses.

Their precaution would prove to be prescient. According to the state police report, a third tank (Tank 200-7), containing 9,730 barrels of gas oil, caught fire in the middle of the night.

The fires continued to reignite periodically until 28 August, leaving four tanks in various states of ruin. That day, news reports expressed relief that the incident was finally over, while continuing to reiterate the official line that there had been no impacts beyond the fenceline. One resident who was found comatose in his home and was hospitalised on 25 August was not released until 1 September.

Marathon’s post-incident reports, replete with gaps, vague statements, and inconsistencies, served more to obfuscate the precise details of the incident than clarify them. In one report submitted to LDEQ, they stated that 22,000 barrels of naphtha had been ‘released to soil’ from just one tank, Tank 150-11, with zero barrels released from the other three tanks. In the same report, they wrote that for Tanks 200-7 and 300-7, material was ‘retained in the tank shell’ throughout the incident, even after both tanks were fully engulfed in flames and largely destroyed. Meanwhile, in a separate report to the EPA’s Risk Management Program, Marathon reported that 28,000 bbl. of ‘flammable mixture’ had leaked from two tanks along with 467 bbl. (140,000lb) of hydrogen sulfide.

In the aftermath of the incident, some residents of Garyville asked Marathon to reimburse the expenses they incurred as a result of the fire, either while evacuating the area, or while seeking medical care linked to chemical exposure. Those residents say they received no response to their requests. The only acknowledgment from Marathon, which reported a net income of $1.55 trillion in 2023, was their offer of a $160 credit on energy bills to residents of Lions.

Future risks

Reports by the state police suggest that ‘high heat and dry grass in the area’ could have been a contributing factor to the incident’s escalation. According to Marathon’s own Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for naphtha, the mixture’s ‘flash point’ is listed as less than 4.4°C (40°F).

A liquid’s ‘flash point’ is the lowest temperature at which, under certain conditions, it gives off vapours in sufficient quantity to form an ignitable mixture of vapour and air—in other words, the lowest temperature at which a nearby spark or flame could cause the liquid to catch fire. On the day of the fire, the ambient temperature of the ground into which the naphtha from Tank 150-11 was leaking would have been substantially higher than 4.4°C (40°F): August 2023 was the hottest month in Louisiana since record-keeping began, with temperatures ranging from 27 to 40°C (80 to 104°F).

Marathon’s Safety Data Sheet also describes naphtha as ‘extremely flammable’. Nevertheless, the available reports make no indication that a fire risk was seriously considered in the twelve hour period between the initial leak and the first reported fire; nor was the risk of reignition after the first fire appeared to die down.

As global temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, incidents like this are likely to become more frequent, and more intense. Meanwhile, state officials urge residents to take responsibility for their own safety while continuing to incentivise new industrial expansion. Community resistance is the only thing that stands in the way.

We conclude with this statement from our partner Joy Banner, founder of The Descendants Project:

‘These industries are becoming obsolete. We need to put our time, our resources, and our energy into industries that are supporting our health, our well-being, and the environment’.

References

1 ‘Cancer Alley’ is most commonly defined as a region spanning 85 miles of the Mississippi River between the Louisiana state capital of Baton Rouge and New Orleans where cancer risk is the highest in the United States. The moniker was coined by environmental activists in the 1980s; in 2018, activists with Rise St James and Concerned Citizens of St John the Baptist Parish offered the additional nickname of ‘Death Alley’.

2 EPA Risk Management Program, ‘Section 6.: Accident History’. Last accessed: 19 March 2024.

3 Minimal Risk Levels (MRLs) are derived for acute (1-14 days), intermediate (>14-364 days), and chronic (365 days and longer) exposure durations https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/mrls/index.html