In Partnership With

Additional Funding

Collaborators

- Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR)

- Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL)

- The Descendants Project

- Earthworks

- Earthjustice

- Healthy Gulf

- Imperial College London

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade

- The Human Rights Advocacy Project (HRAP), Loyola New Orleans College of Law

- The Ethel and Herman L. Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

- Louisiana Museum of African American History

- Whitney Plantation Museum

Forums

Exhibitions

We are currently soliciting feedback on the Louisiana ‘mapping portal’ / interactive platform, particularly from affected local communities, but welcome feedback from all users. Please submit your feedback using this form.

Read the full report here.

In the US state of Louisiana, along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, a heavily industrialised ‘Petrochemical Corridor’ overlays a territory formerly known as ‘Plantation Country’.

When slavery was abolished in 1865, more than five hundred sugarcane plantations lined both sides of the lower Mississippi River; today, more than two hundred of those sites are occupied by some of the United States’ most polluting petrochemical facilities.

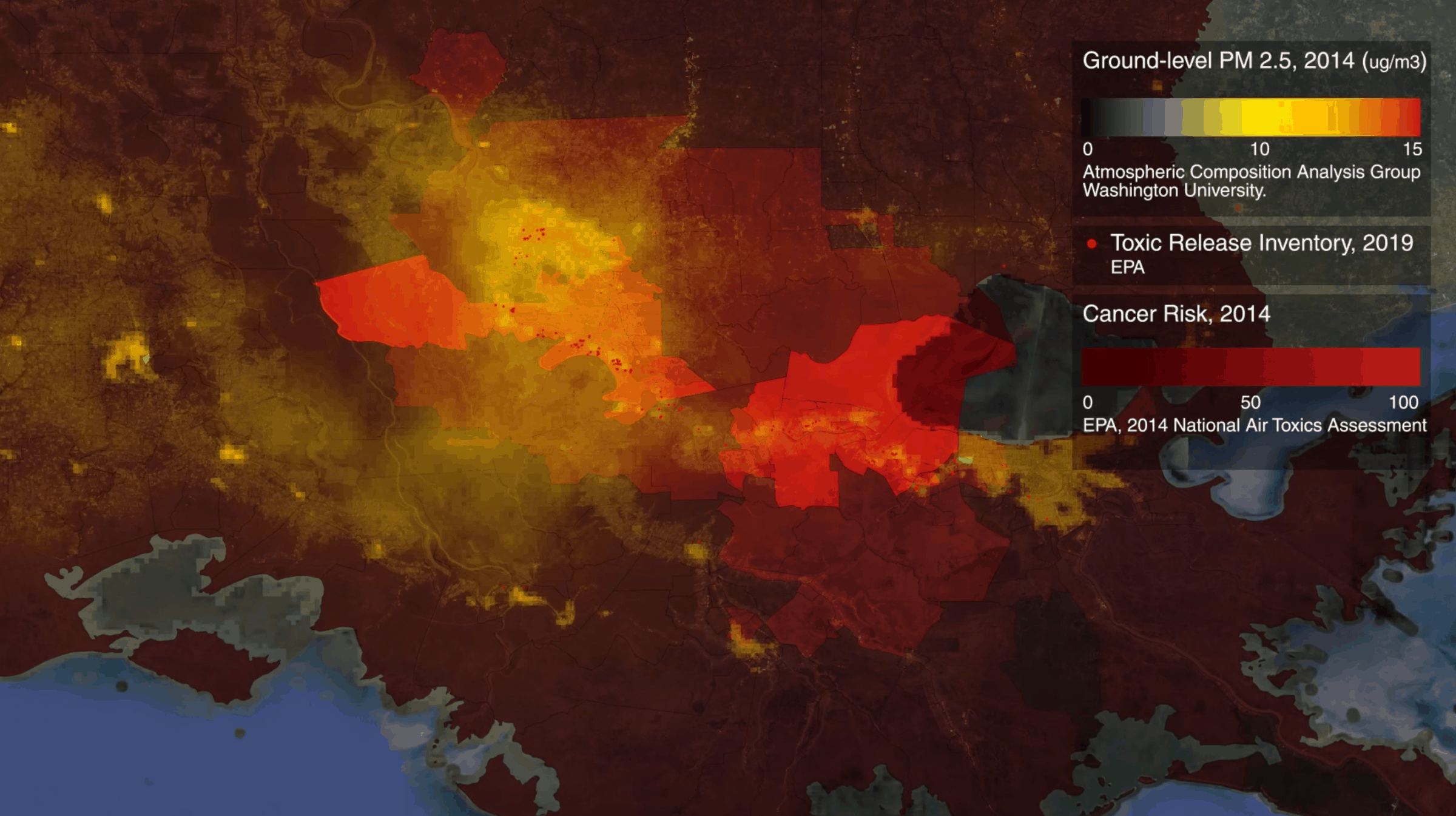

Residents of the majority-Black ‘fenceline’ communities that border those facilities breathe some of the most toxic air in the country and suffer some of the highest rates of cancer, along with a wide variety of other serious health ailments. They call their homeland ‘Death Alley’. Here, environmental degradation and cancer risk manifest as the by-products of colonialism and slavery.

Sugarcane was historically the most dangerous crop to cultivate. To accommodate a negative demographic growth rate among the enslaved population, each plantation established at least one, and sometimes as many as three cemeteries for its enslaved population. The majority of these burial grounds were omitted from historical maps. Over the decades, all outward traces of many of these cemeteries have been erased. On rare occasions, cemeteries resurface – when petrochemical corporations break ground on new construction sites.

In 2015, two cemeteries were uncovered during a survey for a proposed expansion of a refinery owned by Shell Oil Company. Four years later, four more cemeteries were located during the early stages of the construction of a new facility by the company Formosa Plastics. How might we recover the memory of the hundreds, if not thousands, of missing cemeteries at risk of desecration?

Together with fenceline community activist group RISE St. James, Forensic Architecture (FA) has developed a method to help locate these cemeteries in support of longstanding local efforts to protect ancestral sites and demands for a moratorium on the further expansion of the Petrochemical Corridor. All of our research will be open-sourced and made available to the public.

Effects of the petrochemical industry on health and communities

In the period after the American Civil War of 1861-1865, known as ‘Reconstruction’, emancipated Black people formed small towns, which grew from the slave quarters on the plantations of their former enslavement. Over the course of the 20th century, large-scale industrial facilities have been constructed atop those plantations, and historical ‘freetowns’ have since become today’s ‘fenceline’ communities. As polluting industry surrounds these communities, it subjects them to another register of racist violence: assault by invisible toxic chemicals.

Working with researchers from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London, FA developed a fluid dynamics simulation to track the spread of a range of airborne pollutants from three dozen facilities along the Mississippi River under simulated meteorological conditions, drawing on ten years of data from a local weather station. Our simulation reveals the scale and concentration of chemical gassing of communities throughout Death Alley.

The saturation of Black descendant communities with toxic and criteria air pollutants is sanctioned by local and state authorities. In 2014, the governing council of St. James, Louisiana, passed a comprehensive plan that wrote off the district’s majority-Black communities – the hometowns of our partners with RISE – as ‘industrial’ and ‘existing residential/future industrial’ sites.

Broken ground and cemeteries

The erasure and degradation of hundreds of known, suspected, and unmarked burial sites throughout Death Alley is the result of a persistent racist imaginary the regards Black communities and cultural sites as unworthy of preservation, or worse, as a threat to development.

Petrochemical companies are required by federal law to identify historic properties, including cemeteries, that would be threatened by their plans for development. To fulfil this legal requirement, they typically hire for-profit archaeological firms to survey the field, who – with an eye to receiving further contracts – are incentivised to produce favourable reports. Our study of over 50 field reports found a systemic lack of regard for antebellum Black cemeteries.

Read more detail on this in our full report.

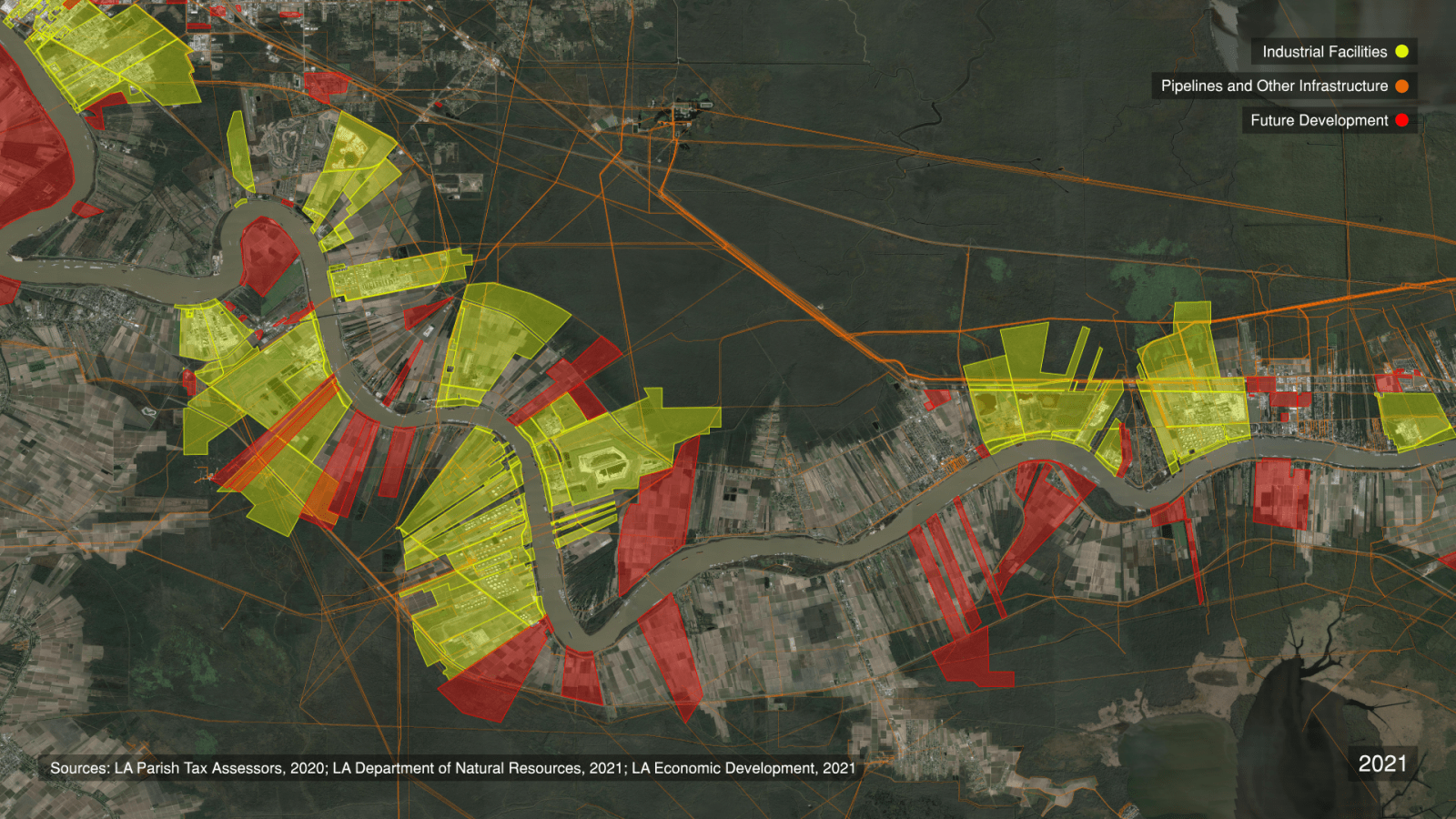

State authorities maintain a list of ‘development-ready’ sites. Around 200 properties throughout Death Alley are deemed ‘ready’ for industrial development by Louisiana Economic Development, a government agency. Yet members of RISE were unaware at the start of our investigation that so much of their homeland was on the auction block.

For generations, Black descendant communities held fast to knowledge of their ancestral sites against the tide of erasure. Today, they search the ground for evidence of these sites’ locations – but are denied access by private landowners.

Our work on this case offers a tool in support of these efforts: we have developed a methodology for determining the probable locations of ancestral cemeteries at risk of future desecration.

Mosaic platform

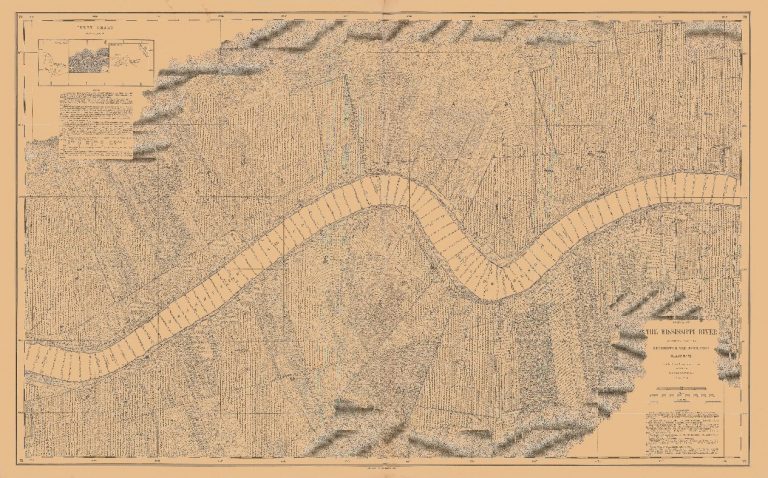

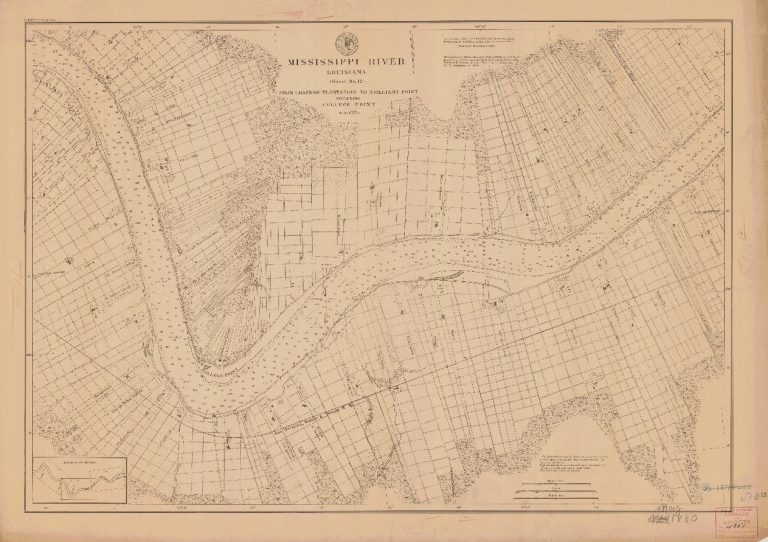

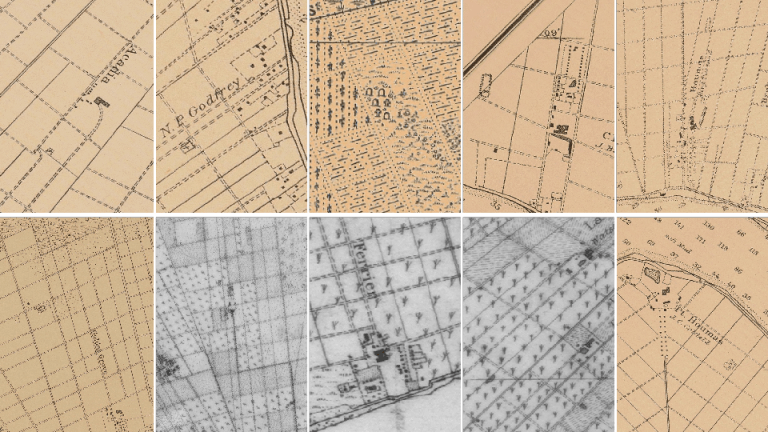

We built a platform that ‘mosaics’ and ‘anchors’ aerial imagery and maps from multiple sources spanning three centuries of the region’s transformation, including the reconstruction of the land according to racist, profit-oriented principles. We began with a 1719 chart of Indigenous territory used by colonists to prefigure the genocidal dispossession of the region’s original inhabitants. From there, we identified US Coast Surveys from 1877-78, Mississippi River Commission charts from 1894, and aerial imagery spanning seven decades, from 1940 to the present.

Plantation logics

Our analysis of these aerial images and maps, along with historical photographs, property surveys, transcripts of interviews with formerly enslaved persons, and other primary and secondary source information about specific plantations, reveals that plantations operated according to consistent spatial and operational logics, determined by the overlapping priorities of a complex which was at once industrial facility, farm, prison, death camp, and luxury estate.

To understand the scale of these logics, we built an interactive 3D environment representing what would have been a ‘typical’ sugarcane plantation within the geography of the lower Mississippi River. (Because no ‘complete’ plantations remain intact, our modelled environment is a composite of several plantations reconstructed using a wide variety of visual and cartographic evidence.)

Through this process, our cartographic mosaics became the ground from which grew structures – including slave quarters and the sugar factory – as simple volumes, before building out detail from archival photographs. Using topographical features of the USCS 1877 and MRC 1894 maps, we then constructed the topography, roads and field paths, crop classifications, and cypress forest. For the atmosphere, we referenced contemporary satellite imagery and drone footage.

Reading the earth

As plantations reorganised life, they also managed death. The spatial logics of the plantation also dictated the siting of Black cemeteries. Slave masters would not sacrifice valuable land for Black cemeteries. Enslaved people were thus interred in uncultivated lands at the back of the plantation, at the ever-retreating edge of the cypress forest.

Denied stone, enslaved people often crafted simple wooden grave markers, which naturally decomposed over time. And sometimes, drawing on pan-African traditions, they planted magnolia and willow trees to mark the graves of their loved ones, cultivating ‘sacred groves’.

Sugarcane was a crop of scale; as plantations expanded from the mid-1820s until the Civil War, cemeteries became islands of trees and vegetative overgrowth, isolated amid seas of sugarcane.

Clusters of trees or uncultivated patches of land that interrupt an otherwise unbroken topography of agricultural fields are referred to by archaeologists as ‘topological anomalies’.

Through our research, we have found that some anomalies are the ruins of slave quarters or industrial sugar factories. And some are revealed to be the cemeteries of the formerly enslaved.

In the years after emancipation, the region underwent a process of spatial, economic, and social Reconstruction. Some cemeteries remained in continuous use, while others were lost to time. As industrial development has expanded, many of the anomalies we identified have been erased.

Probability fields

The surface traces of many cemeteries were likely razed prior to 1940, when the first available set of aerial photographs was captured. In the absence of earlier photographic traces, we determined that we could estimate the probable locations of cemeteries by combining multiple factors of ‘plantation logics’ drawn from our cartographic analysis.

Traditional archaeology focuses on the slave master’s ‘Big House’, and other relics of white supremacy, considering the topographically elevated riverfront areas of plantations as zones of ‘high probability’ for finding cultural resources, and the low-lying areas toward the back of the plantation as ‘low probability’. Our analysis inverts this principle, determining that those areas away from the riverfront have a higher probability of holding valuable Black heritage sites, including cemeteries.

Additional factors include the boundaries of the forest at different periods in time, the boundaries of plantation properties, the location of roads and field paths, and the location of living quarters for the enslaved population and the industrial sugar mill. Bringing these factors together within our computer software generates what we refer to as a ‘Field of Probability’.

Conclusion

Through the lens of the petrochemical plantation burial ground, Death Alley is revealed as a 300-year continuum of environmental racism.

To confront that continuum, the whole ecology of the region must be considered of utmost cultural value: from the fields where the enslaved were born, worked to death, and buried, to the surviving forests, which under the cover of night became sites of ritual, mourning, and liminal freedom, to Black descendant communities who deserve to inherit far more than a legacy of violence, discrimination, and erasure.

The Black descendent community has long voiced demands for accountability from the petrochemical corporations that occupy their lands. Today, this demand is building into a broader vision of justice: reparations for centuries of racist violence, the repair of the environment, jobs that sustain their communities and their health, a moratorium on industrial development, and agency over how their land is stewarded. Moreover, they demand a fundamental revision of the concept of historic preservation toward a recognition of Black communities, ancestral sites, and our wider ecologies as intrinsically valuable, indivisible, and worthy of protection.

Update

12.02.2021

12.02.2021

FA researcher Imani Jacqueline Brown reported on early stages of the investigation as a featured expert on environmental racism during the 2021 Human Rights and Climate Change Geneva Dialogues in a workshop themed ‘Creating a just climate for fighting climate change: How can UN human rights mechanisms contribute to ending environmental racism?’

Update

02.03.2021

02.03.2021

Fourteen UN experts released a statement condemning the perpetration of environmental racism in Death Alley, Louisiana, by state and corporate actors. The statement is a response to a formal complaint on the subject drafted and submitted by a coalition of partners, including Forensic Architecture, to the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, an organ of the United Nations Human Rights Council.

In their statement, the experts note that the ‘construction of the new petrochemical complexes will exacerbate the environmental pollution and the disproportionate adverse effect on the rights to life, to an adequate standard of living and the right to health of African American communities’. They further ‘expressed concerns at possible violations of the cultural rights of the affected African American communities in the area, where at least four ancestral burial grounds of enslaved Africans are at serious risk of destruction by the construction of the Sunshine Project’.

Update

24.03.2021

24.03.2021

FA researcher Imani Jacqueline Brown attended a high-level session of the Geneva Dialogues on Human Rights and Climate Change, called ‘Human Rights Institutions and the Implementation of the Paris Agreement’. The Human Rights and Climate Change Geneva Dialogues were organised by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), a collaborator on FA’s investigation, as well as the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Earthjustice, and Natural Justice, with the support of the Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

Update

24.03.2021

24.03.2021

The United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent (WGEPAD) hosted its 28th public session, organised around the theme of ‘environmental justice, the climate crisis and people of African descent’. FA submitted input and contributed to the planning of this session, connecting the WGEPAD with our investigative partner Sharon Lavigne, founder of RISE St. James.

Update

05.08.2021

05.08.2021

FA submitted input to the 2021 report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, drafted on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action. The submission included a summary of our investigative report.

Update

26.10.2021

26.10.2021

FA was informed that our contribution to the report will be presented at the UN General Assembly.

Update

05.2022

05.2022

FA submitted an affidavit and expert report to a legal suit filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and the Descendants Project in St. John the Baptist Parish, at the heart of Death Alley. The case challenges the planned construction of the Greenfield Development, a massive industrial grain terminal planned to cross several antebellum plantations, including the Whitney Plantation, a central site in our investigation. The Plantation is now the location of the Whitney Plantation Museum, the only museum to slavery in a region infamous for hosting weddings in the ‘Big Houses’ of slave masters. Our affidavit submits that the development would likely destroy several anomalies located in the high probability zone of our Probability Field model.

Center for Constitutional Rights filed an emergency request for a temporary restraining order (TRO) on behalf of the Descendant’s Project to prevent the grain elevator company from conducting ground-disturbing construction activity on the project site in order to protect burial grounds of people once enslaved there. After revelations about whistleblower concerns for sacred Black history, CCR filed a motion to supplement its motion for a temporary restraining order with the newly reported information on behalf of the Descendants Project.

Update

21.03.2023

21.03.2023

St James Parish residents — Inclusive Louisiana, Mt. Triumph Baptist Church and RISE St James — have issued proceedings against the Parish, after requesting a moratorium on the construction of new petrochemical plants and related infrastructure in 2019. Their request having been ignored, and approvals for a new petrochemical facility having been granted by the council, led to the newly filed suit, which plaintiffs argue will not only address the harms caused by the parish council to majority-Black districts, but will improve the lives of all parish residents. Forensic Architecture’s research, namely maps showing the locations of unmarked cemeteries of people once enslaved in St James Parish, has been presented in support of the claim.

Update

24.04.2024

24.04.2024

Last month, with Rise St James and The Descendants Project, we celebrated the launch of a new interactive platform, an extension of our research into environmental racism in ‘Death Alley’, Louisiana. This online ‘mapping portal’ makes our research accessible to the public, offering a new tool to local residents and their allies seeking to protect their history and future from industrial erasure. You can use it to travel back and forth in time across a 60-kilometer area, investigating the transformation of the land from ‘Plantation Country’ to the ‘Petrochemical Corridor’. The portal reveals the scale of this landscape’s cultural and historic value, which we can still protect and recover.

Methodology

Methodology

Cartographic Regression

To process and analyse the maps and aerial imagery, we employed a methodology called ‘cartographic regression’. Cartographic regression refers to the process of overlaying historical surveys, maps, and aerial photographs onto contemporary aerial imagery to track the transformation of the land and specific elements of the territory over time. While this methodology is increasingly used in archaeological surveys for evaluating probable locations of cultural resources, it is almost exclusively applied in localised and small-scale studies. FA built upon existing studies to expand the scope and reach of “cartographic regression” in several ways:

1. We georeferenced and ‘mosaiced’ all the available maps and imagery within QGIS, an open-source Geographic Information System application. (‘Georeferencing’ is to associate an image with a geographic coordinate system, anchoring it to the ‘real world’; ‘mosaicing’ is to stitch together aerial images or maps to create single images covering much larger areas.) This facilitated the flexible handling and superimposition of hundreds of different images covering a much larger area than what a ‘photographic’ overlay would normally allow. Once they are georeferenced, the maps and imagery are then ‘anchored’ within the platform, and their visibility can be flexibly adjusted or toggled on and off. This blending of cartographic regression with GIS spatial techniques enabled the processing of a vast number of resources, covering almost 300 years of land transformation.

2. Once anchored in the platform, information from historical charts and maps was vectorized classified according to specific categories: cemeteries, plantation property borders, canals, paths and roads, structures, and topographical elements such as elevation contours. That process informed the computational generation of the “field of probability.” Similarly, the aerial photographs were read and analysed decade-by-decade until the present day, tracing the region’s topographical transformation, including ‘anomalies’.

3. To complement our remote analysis and calibrate the historical resources to the present day, we combined cartographic regression with “ground truth” – a technique of anchoring the results of a computational or digital process to a precise location in the real world. This is done by comparing measurable data on the ground, such as the GPS coordinates of a specific, recognisable landmark, to the contents of that digital process, in this case the GIS cartographic portal. “Ground truthing” a digital model helps us to connect the results of our technical analysis to conditions in the real world.

Field of probability

To estimate the location of cemeteries without topographical traces, we developed a cartographic technique that we refer to as a ‘field of probability’. This field is intended to determine the level of likelihood that a Black cemetery exists with a given area. The field is created in application Rhinoceros 3D. The algorithm is created by Grasshopper, a visual programming language and environment that runs within Rhinoceros 3D, along with cartographic vector data from the 1878 and 1894 maps, exported from QGIS. The field itself is comprised of a mesh of pixels, each the approximate area of a tree.

Anomalies that fall within this field must urgently be protected and investigated through careful and respectful archaeological survey. Moreover, the entire landscape is revealed as holding historical and cultural value that we can still recover.

Video, 35:04

(from top, left)

Whitney Plantation Big House. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no.1983.47.4.1119

Evan Hall Plantation Big House. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.89

Houmas Plantation Big House. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no.1981.247.1.949

San Francisco Plantation Big House. The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1974.25.26.124.

Oak Alley Plantation Big House. The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no.1979.89.7392

(from top, left)

Survey of Houmas Plantation dated 25 June 1821. The Historic New Orleans Collection,

Courtesy of Dr. Robert C. Judice, EL.25.1988

Cutting Sugar Cane. The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 2010.0095.53

Whitney Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mr. Sam R. Sutton, acc. no. 1984.166.2.539

Slave Quarters, Evan Hall Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of

Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.8

Sugar House, Evan Hall Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of

Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.93

Slave Quarters, Evergreen Plantation. The Clarence John Laughlin Archive at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. 1981.247.1.982

Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.8

Sugar House, Evan Hall Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of

Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.93

Cane Shed, Evan Hall Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of

Ms. N. West Moss, acc. no. 2016.0386.1.1.95

List of Slaves on Houmas Plantation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, acc. no. MSS 294, folder 44