In Partnership With

- Nama Traditional Leaders Association (NTLA)

- Ovaherero Traditional Authority (OTA)

Additional Funding

- Kulturstiftung des Bundes

- Gerda Henkel Stiftung

Collaborators

- Medico International

- European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR)

- Namibia Genocide Association

Methodologies

Forums

This investigation is the latest instalment of our project on the genocide perpetrated against the Nama and Ovaherero people by Imperial Germany, in what is today Namibia. Conducted in partnership with Ovaherero and Nama activists and traditional leadership, this investigation focuses on the harbour town of Swakopmund.

From 1904 until 1908, Swakopmund housed a concentration camp run by the German colonial army. Together with descendants of survivors and activists, we reconstructed the town as it existed during the genocide, revealing the long-forgotten location of the camp, alongside many sites of forced labour throughout the town’s fabric. With forensic archaeologists, we investigated the unmarked graves of the camp’s victims at the edges of the town, revealing how they have been disturbed and destroyed by urban development.

Ovaherero and Nama groups continue to call for the urgent preservation of the burial grounds of the genocide victims, in Swakopmund and across the region. The project supports wider efforts to ensure the long overdue protection of the unmarked graves in Swakopmund and to promote education efforts that counter genocide denialism still present in Namibia.

Introduction

Swakopmund is located where Namibia’s Swakop River flows into the Atlantic. In Khoekhoe, the language of Nama and Damara people, the river’s name is Tsoaxaub, a name which refers to the movement of sediments and detritus carried by the river.

The town was established in 1892, as the primary seaport for a growing colony. Two years later the Hamburg-based shipping company Woermann began trading in the region, basing their headquarters, the Woermann Haus, in Swakopmund. Woermann facilitated the transport of goods, people, and weapons, between Swakopmund and Hamburg, playing a crucial role in the expansion of the colony of German South West Africa.

Over time, Imperial Germany refused to tolerate the independence and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. In 1904, after a military victory against an Ovaherero force at Waterberg, the German general Lothar von Trotha issued an extermination order against all men, women, and children of the Ovaherero. Those who survived the waves of violence that followed the orders were rounded up at ‘collection points’ across the colony and taken to concentration camps, where they were subjected to brutal conditions and forced labour.

This investigation combines oral history and archival research with digital spatial analysis to determine the precise location of the Swakopmund concentration camp, as well as further sites of forced labour scattered across the town. This body of digital evidence substantiates the claims of Indigenous communities, whose histories have been disregarded and denied, just as the camp itself has been erased. Today, no plaques or markers acknowledge the site’s dark past.

Locating forced labour

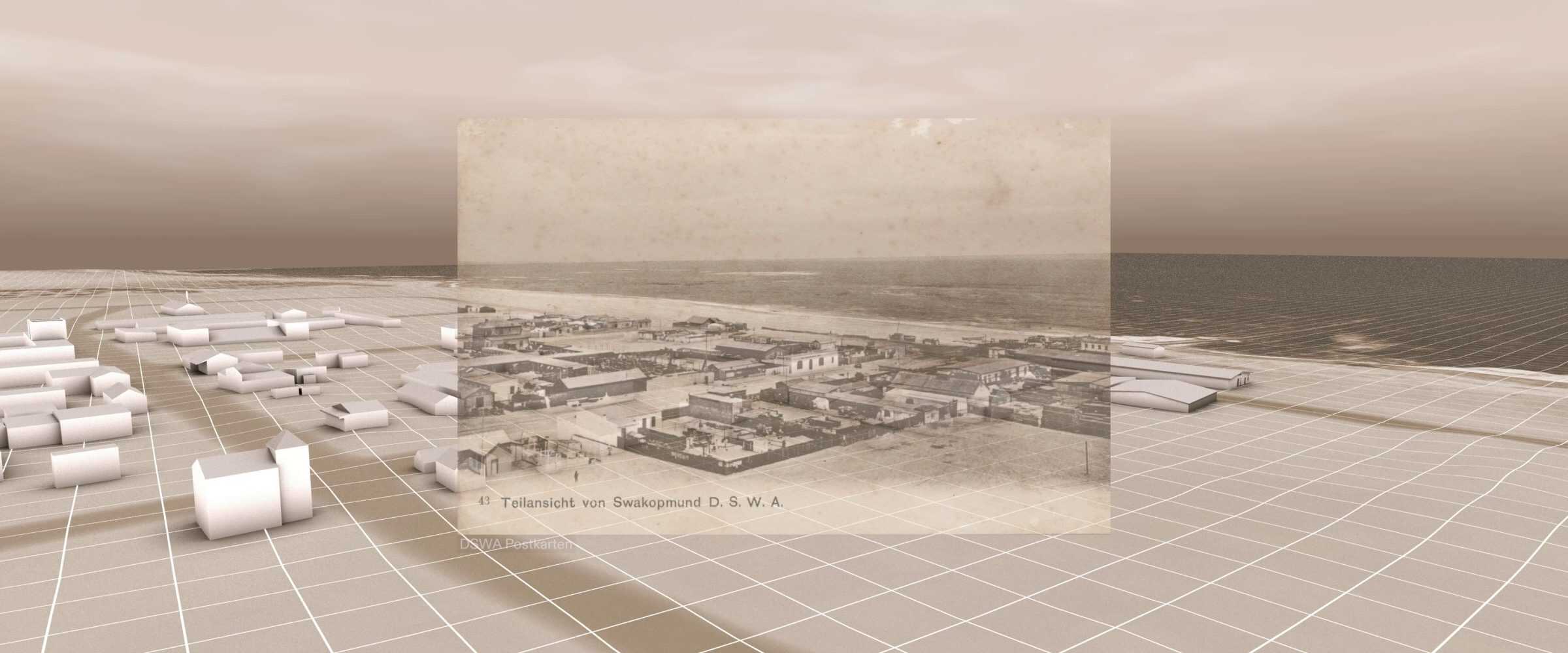

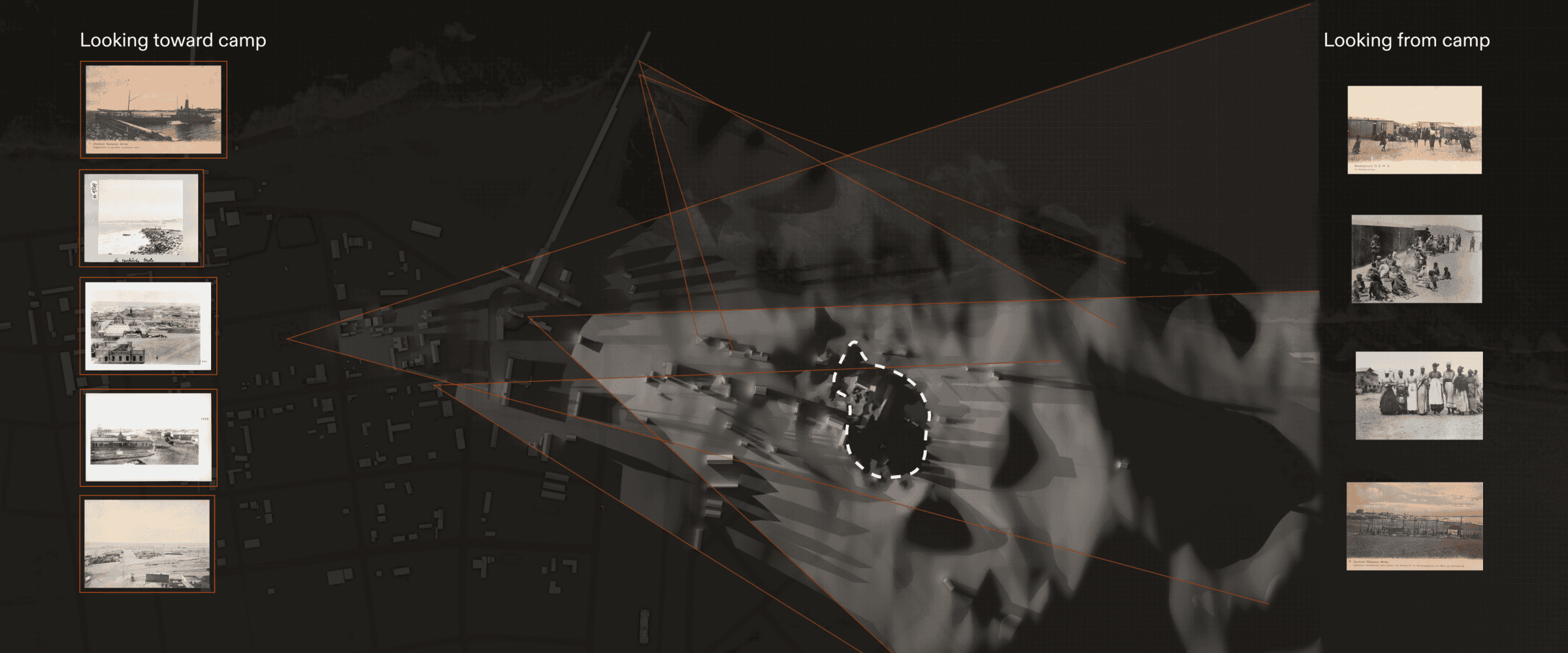

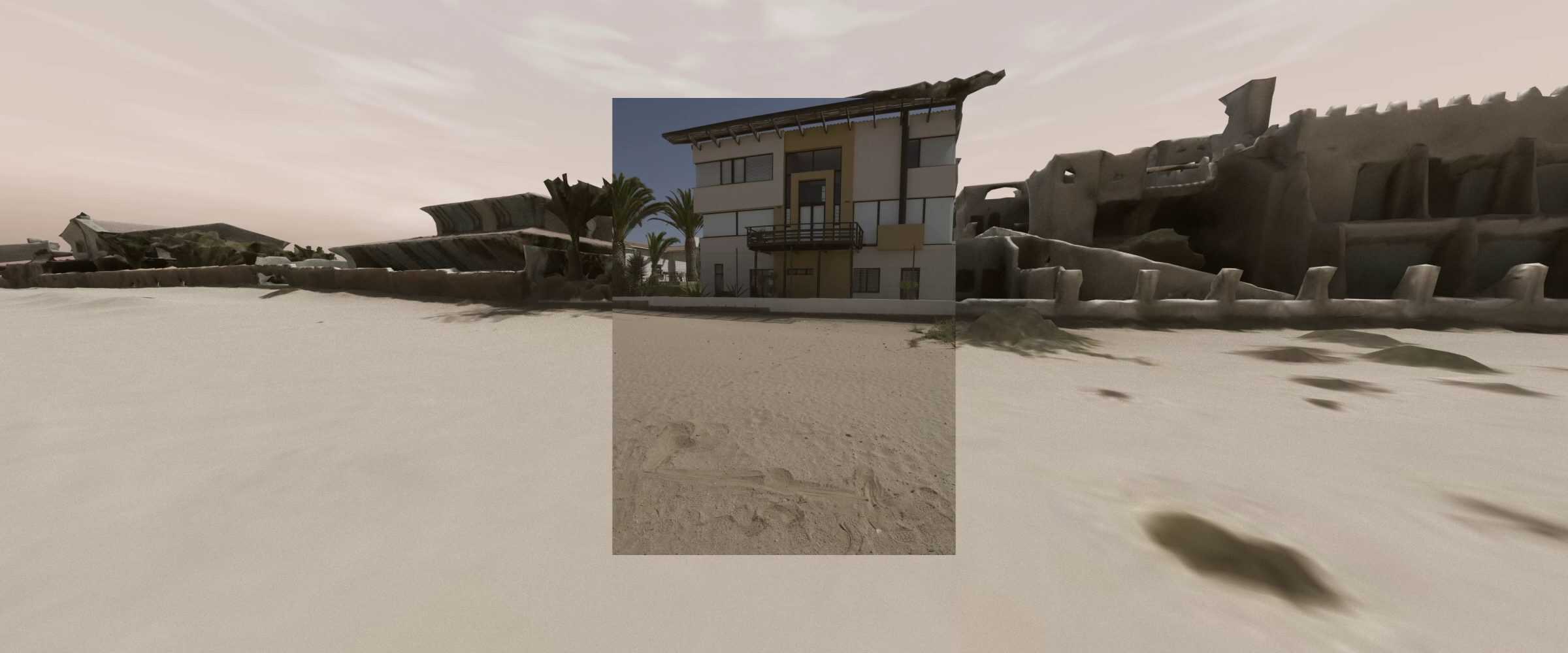

From archival images, we reconstruct the town as a digital model, as it was during the period of the genocide. A series of six postcards, likely all taken in 1907, were taken from a vantage point at the top of Woermann tower. These postcards provided a 360-degree view of Swakopmund.

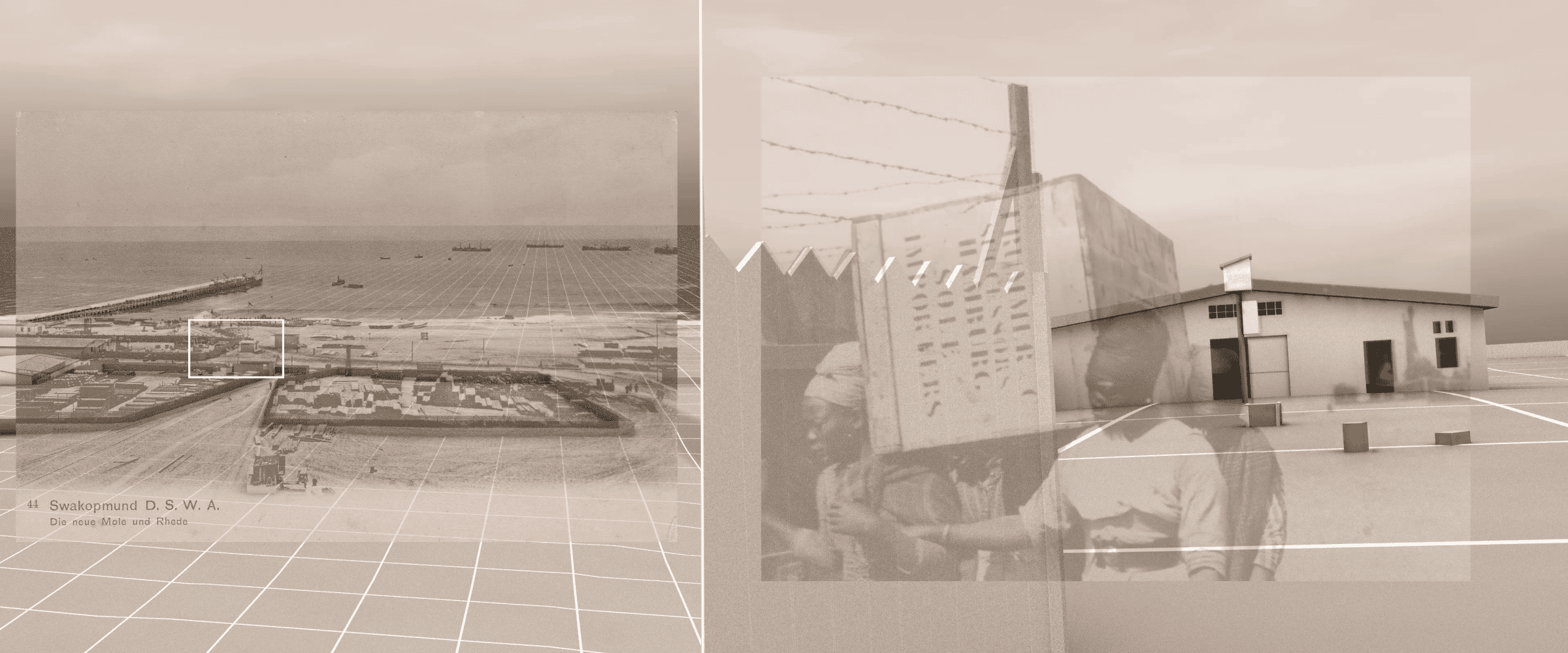

The images taken from this vantage point above the town helped us to locate images taken at ground level, such as this image of Herero women carrying a large shipping crate. Swakopmund operated on a system of forced labour managed by Woermann.

Finding the 'Lager'

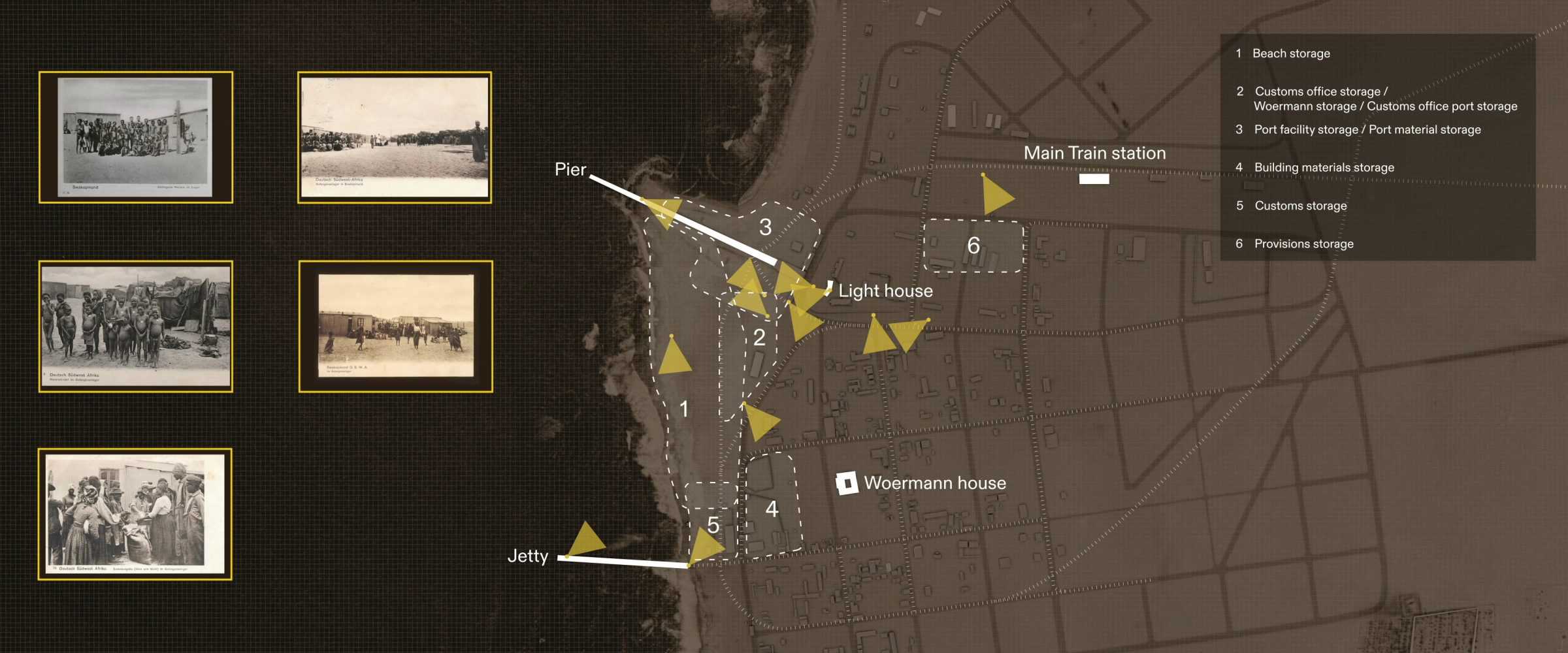

We examined hundreds of photographs of Swakopmund taken between 1904 and 1908, which referred to ‘Lager’ in their metadata. These storage facilities existed within Woermann’s logistics network, relying on the labour of captives to function. These images, and the information in their metadata, allowed us to map that network, identifying six zones of operation across the town.

However, a handful images proved difficult to geolocate. All these images depicted what was described as the ‘Gefangenenlager’ – or ‘prisoners’ camp’.

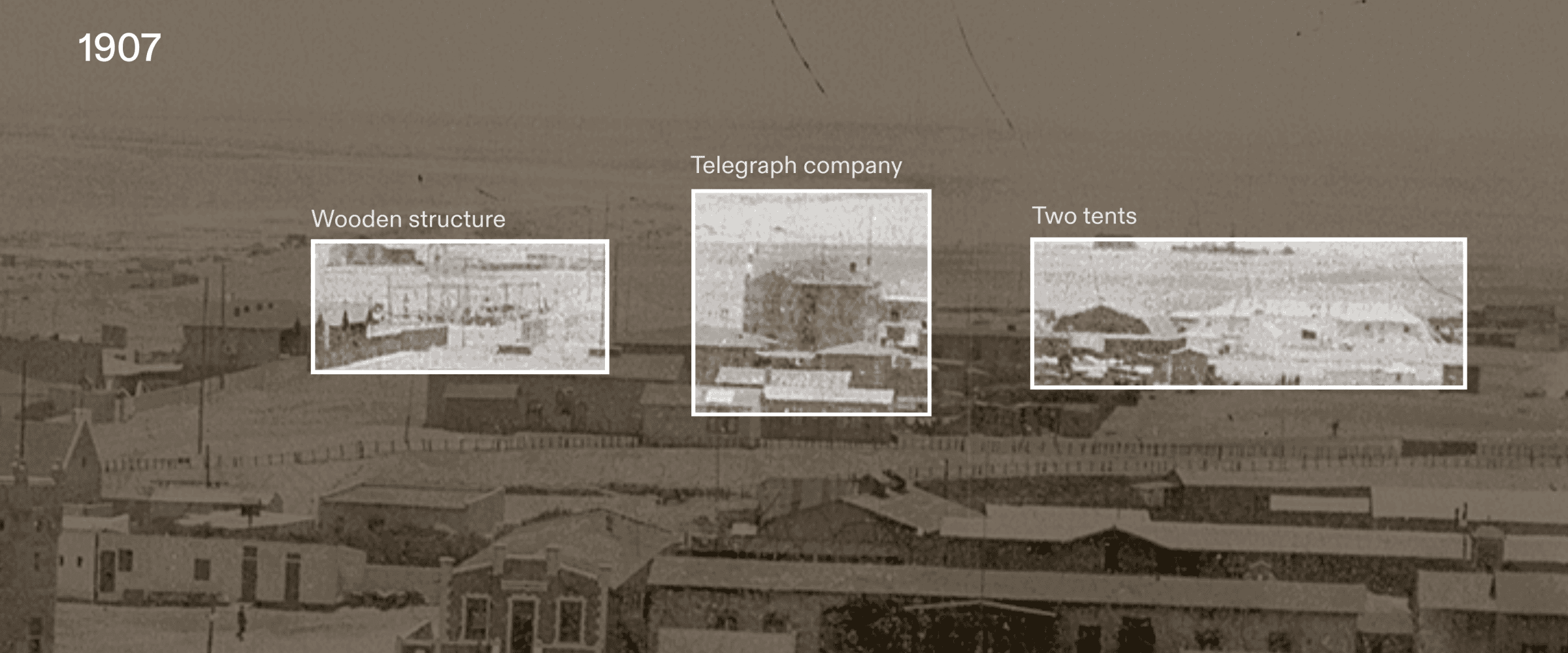

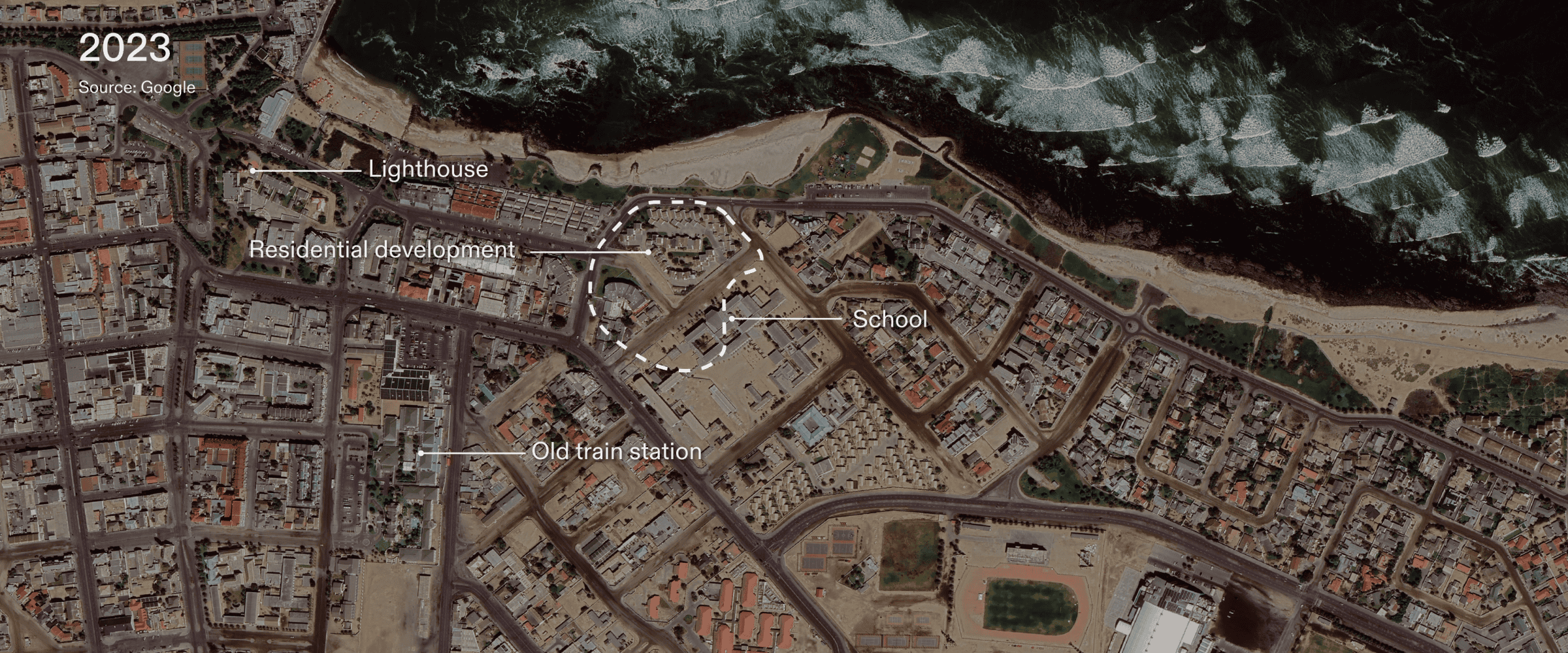

Two photos captured the same area to the north of the town. One was taken in 1907, during the genocide, while the other was taken in 1912, after its end. Comparing the images reveals that a group of tents and structures were present on the north side of the town during the genocide period, but were disassembled in the years after the genocide concluded. This area was very likely the Gefangenenlager; Swakopmund’s concentration camp.

Our film describes a ‘sight line analysis’ within our digital mode, which demonstrates the parts of the concentration camp that would have been visible from archival photographs, revealing how the region’s topography was used to conceal the camp’s presence from the sight of the town.

After the closure of the camp, traces of it have been erased. The valley along the shoreline where the camp was located has since been developed into housing, and there is no acknowledgement of its historical presence.

Burial grounds

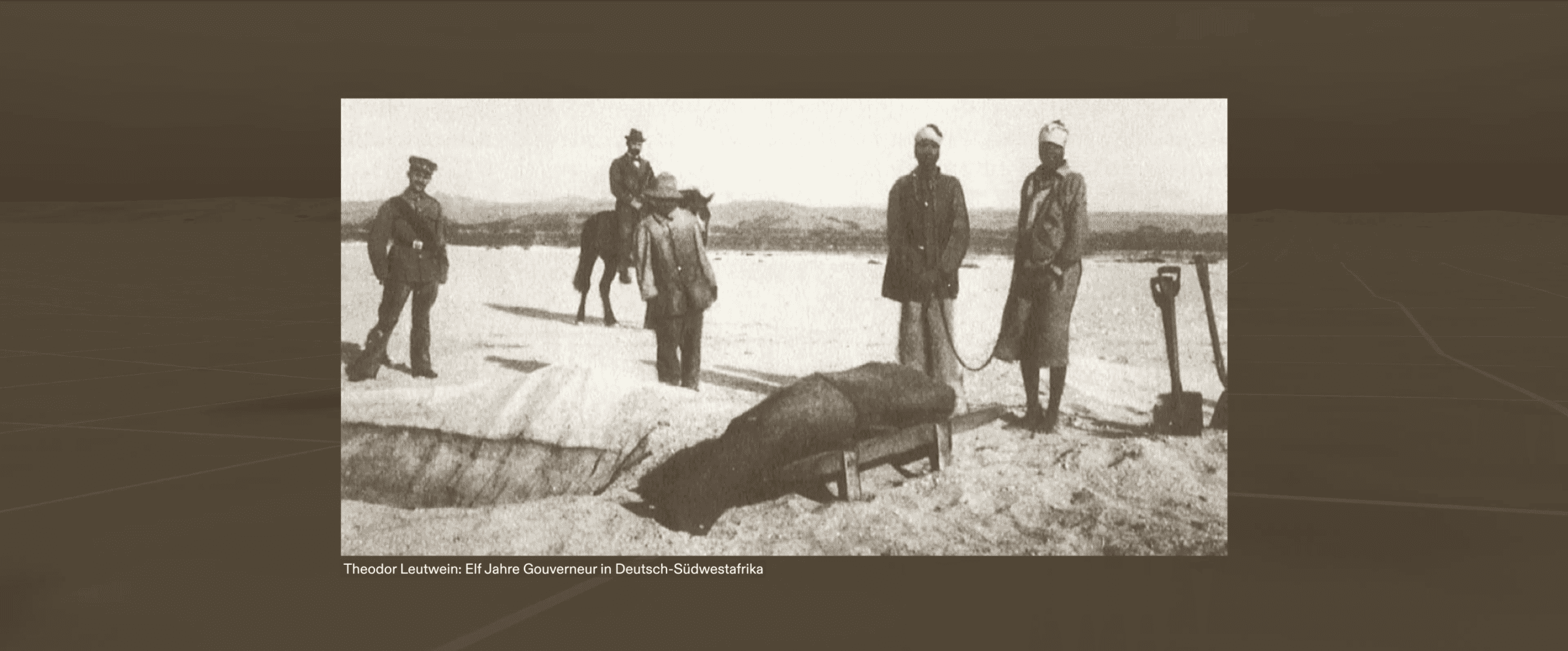

It is estimated that between two and three thousand Ovaherero and Nama prisoners died in Swakopmund during the genocide. At a large burial site, situated along the river at the town’s edge, hastily dug graves are each indicated by a mound of sand. Prisoners were forced by their captors to bury their fellow captives in shallow, unmarked graves, often disregarding traditional Ovaherero burial practices. Our aerial survey of the site identified just over 2,500 visible burial mounds.

The boundaries of this burial ground are recorded in city documents from the 1900s. In satellite imagery spanning from the 1980s to the early 2000s, the tracks of dune buggies are visible in the same area, criss-crossing the graves. In 2006, descendants of the victims forced the municipality to construct a wall around the unmarked graves to help protect them from further desecration.

However, as our cartographic research reveals, this protection has come too late for graves on the northern edge of the burial ground. The 2006 perimeter wall was constructed along the outer boundaries of a row of luxury houses that were already encroaching on the burial ground. According to the local activists, remains have been found during construction work on the northern edge of the plot.

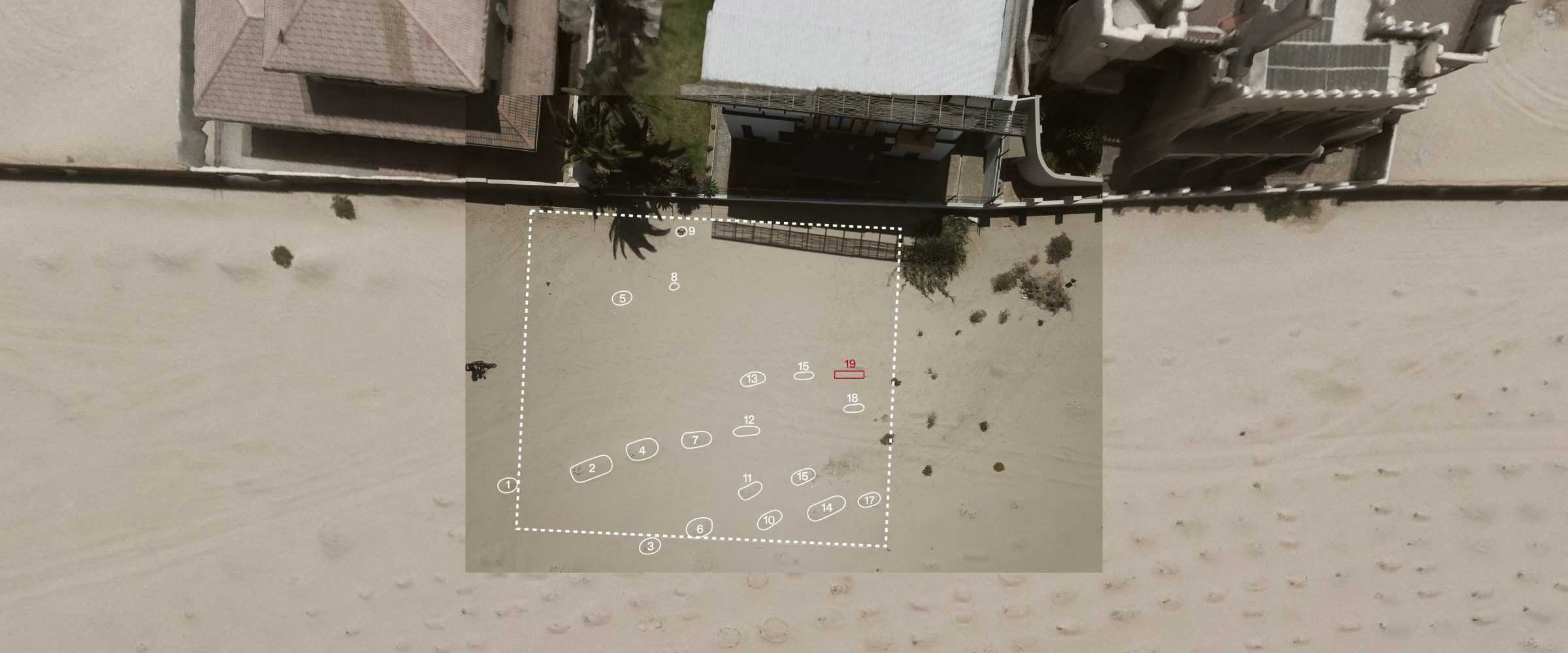

When Forensis and Forensic Architecture (FA) visited the site in 2023, two partially exposed coffins were visible, near the luxury houses on the northern edge of the burial ground. We commissioned a team from the Centre for Archaeology at Staffordshire University to conduct ground penetrating radar (GPR) scans of this part of the site.

GPR is a non-invasive technique that detects differences in subsoil density and composition, by transmitting radio waves into the ground. The Centre for Archaeology compiled a report based on their GPR surveys in Swakopmund and in Radford Bay, Lüderitz, which you can read here.

Within a survey area adjacent to the housing development, nineteen visible mounds were observed. GPR data produced subsoil signatures consistent with graves at each mound, confirming the likely presence of human remains. Additionally, the GPR revealed six more likely graves beneath the surface that were not associated with any visible mounds, suggesting that across the burial site, there may be more graves than the 2,500 mounds indicate.

This data corroborates testimonies of local activists, that some grave mounds have been flattened during construction works, or afterwards, by residents. Despite appeals to the municipality, those activists claim that little more has been done to protect the mounds.

Another GPR survey was conducted on a vacant lot adjacent to the housing development, which falls within the historical boundaries of the burial site. In this area, where no visible surface mounds were observed, three subsurface anomalies were detected which exhibited characteristics similar to those of the graves marked with sand mounds.

The findings of our GPR surveys highlight the urgent need for a full survey of the burial ground, as well as its protection. Despite the site’s significance, Namibian and German authorities do little to support descendant communities, who care for these graves just as the camp’s prisoners themselves once did. Four times a year, the Swakopmund Genocide Museum organises volunteer efforts to rebuild these mounds.