Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

On 29 October 1948, al-Dawayima was one of several Palestinian villages targeted as part of a military campaign initiated by the newly established State of Israel aimed at the dispossession and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. Over the course of the day, Israeli forces from the 89th Battalion entered al-Dawayima, destroying homes and infrastructure and forcibly displacing its population.

Survivors have recounted the systematic massacres of civilians—men, women, children, and the elderly—across multiple locations in and around the village, including the village mosque during Friday prayers, the threshing floor of the local market, and outside the Tur al-Zagh cave, where many had fled as the attacks unfolded.

Nakba as a strategy

These events were part of the Nakba (‘catastrophe’ in Arabic), the historical period between 1947 and 1949 during which over five hundred Palestinian villages were depopulated, and their residents killed or displaced in a deliberate Zionist effort to establish a Jewish-majority state. This strategy included widespread massacres, forced expulsions, and the systematic destruction of villages, cultural heritage, and agricultural lands to prevent the return of refugees. By the time the State of Israel was established on 14 May 1948, half of the total number of native Palestinians had already been forcibly expelled from their homes.

This investigation understands the Nakba not only as a historical event, but as a strategy. In Palestine, the Nakba is an ongoing settler-colonial process aimed at systematically erasing the Palestinian people and their indigenous landscape—a process that has entailed exponentially more militarised, surveillant, technological, and destructive Israeli practices employed against Palestinians.

As such, the 1948 depopulation and destruction of al-Dawayima and the massacre of its Palestinian inhabitants should not be read as an isolated incident but rather as part of a long continuum, from which we may derive vital historical context for understanding Israel’s ongoing settler-colonial genocidal campaign in the country.

The attack on al-Dawayima

Days before the occupation of al-Dawayima, other nearby Palestinian villages had been occupied and their Palestinian residents expelled: Bayt Jibrin was occupied on 23 October 1948 and Qubayba on 24 October. Displaced families from these villages sought refuge in al-Dawayima.

In the afternoon of 29 October, Israeli forces attacked al-Dawayima, invading the village from three directions at once. Some of the village’s inhabitants fled to the west in the direction of Gaza, and others eastward toward what is now the occupied West Bank, many later continuing to Amman in Jordan.

Survivors have recounted systematic massacres of between 70 and 450 men, women, children, and the elderly across multiple locations in and around the village—with one of the largest massacres taking place outside a cave called Tur al-Zagh, where many had fled as the attacks unfolded.

Palestinian survivors called it ‘another Deir Yassin,’1 while Israeli ministers later admitted to their soldiers committing ‘Nazi-like acts’2 during the attacks. Ten days after the invasion, on 8 November 1948, Belgian and French personnel, acting as observers on behalf of the UN, were taken to al-Dawayima by Israeli liaison officers. They wrote in their report:

‘I noticed about 15 places where houses were still smoking after having been burnt and the roofs were caved in through the fire. Later or while passing some of these houses there were quite a few that gave a peculiar smell as if bones were burning but I couldn’t see anything through the caving of the roofs. These were burnt to get the vermin out so they said.’

On that same day, a letter was sent by an Israeli soldier named S. Kaplan to the editor of the Israeli Al-Hamishmar newspaper calling for an investigation into the massacre in al-Dawayima. Kaplan wrote:

‘There was no battle and no resistance….

The first soldiers [to enter the village] killed from 80 to 100 [male] Arabs, women and children.

They killed the children by smashing their skulls with sticks. There was not a home without its dead.

Arab men and women who remained in the village were shut into houses without food or water.

One soldier boasted that he had raped an Arab woman and then shot her.

[…] cultured, polite commanders… turned into base murderers, and not in the heat and passion of battle but in a system of expulsion and destruction. The fewer Arabs that will remain, the better.’

After its depopulation, the village was systematically looted, and its cultural heritage destroyed.3

Scope of Study

In collaboration with the Palestine Land Society, Forensic Architecture analysed cartographic and photographic evidence, written testimonies, and archival documents concerning the spatial layout of al-Dawayima before and after the 1948 invasion, with the aim of:

- locating and outlining the original village structures and roads;

- identifying the likely location of one of the major massacres near the cave of Tur al-Zagh;

- and identifying the likely location of the kiln where the bodies of those massacred were later buried.

We conducted ‘situated testimony’ interviews with living witnesses and survivors of the Tur al-Zagh massacre, Abu Bassam and Umm Nasser, who were ten and around three years old, respectively, at the time.

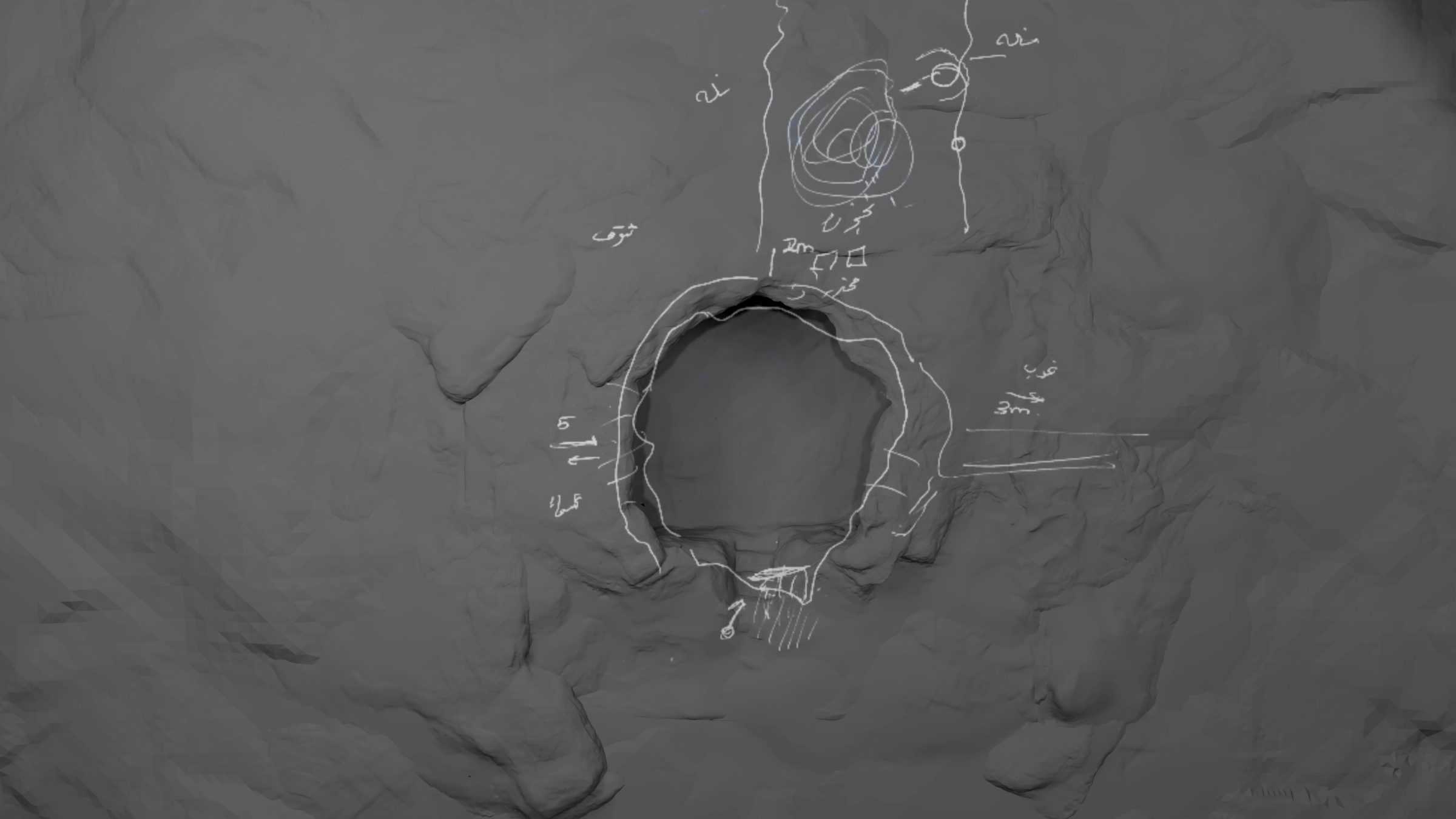

The witnesses provided invaluable details about the incident and the layout of the village, creating drawings and clay models to aid our modelled reconstruction of the village and the cave of Tur al-Zagh, a place long erased from the contemporary landscape.

All that remains

Following its invasion in 1948, al-Dawayima was flattened to make way for a new settlement.

By 1965, Israeli forces replaced the initial, more temporary structures with more permanent ones, designed for Israeli-Jewish settlement expansion. By 1969, the land was scraped and scarred once more to prepare the terrain for further settlement construction.

Aerial images dated from 1945 to the present show the evolution of the settlement on al-Dawayima lands.

Today, the likely sites identified by our research are buried under the Israeli settlement Bnei Dekalin, as is the kiln where the remains of the victims may have been left.

Alongside the vivid memory of its surviving inhabitants, what remains of al-Dawayima today is a shrine to Sheikh Ali, outside of the village, along with traces of the walls of original Palestinian agricultural plots, and the ruins of a few homes.

Methodology

Methodology

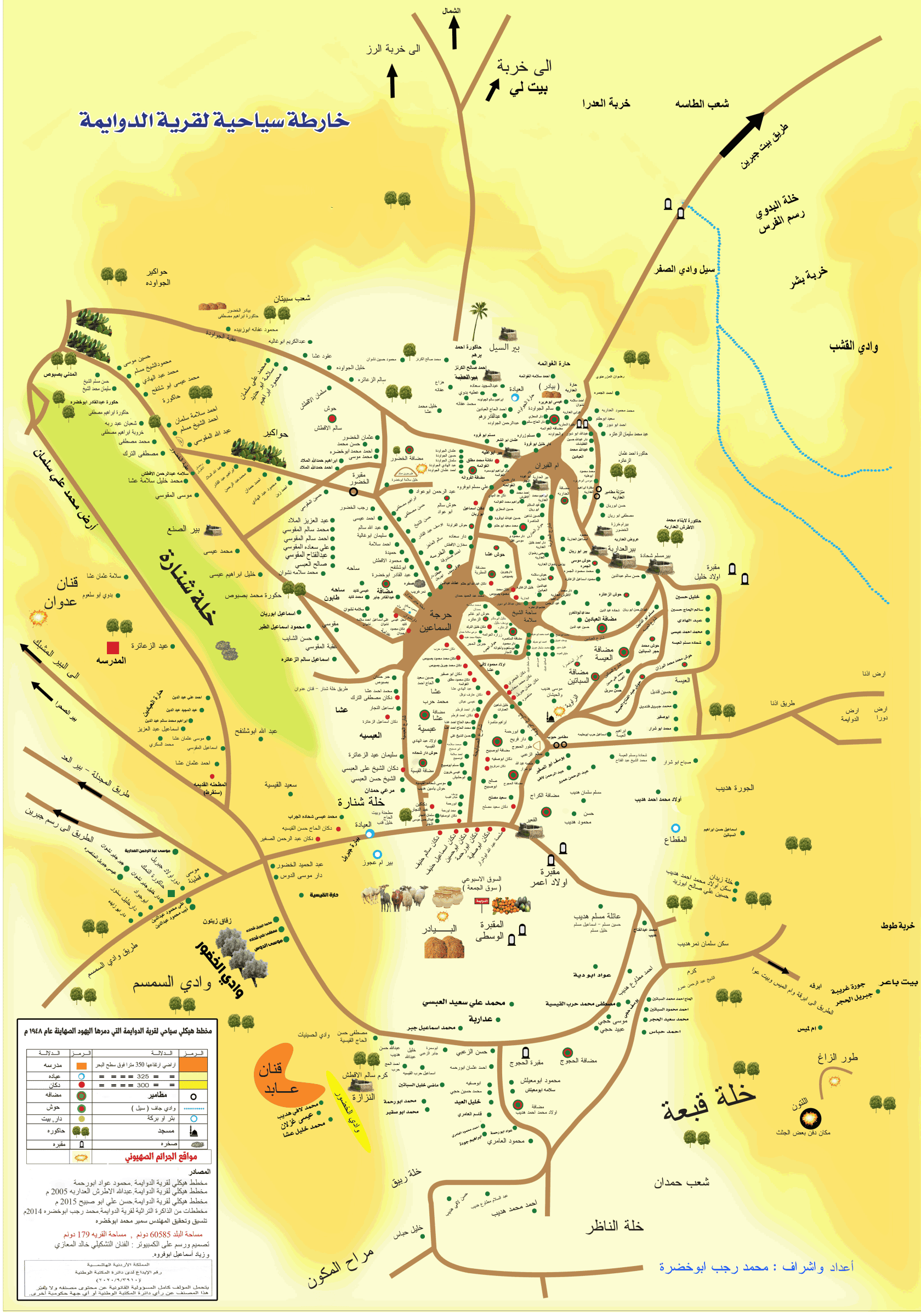

Key to our investigation were multiple ‘memory maps’ produced by an Amman-based researcher from al-Dawayima, Mohammad Rajab Abu Khudra, known as ‘Abu Yasser’. A ‘memory map’ is a type of map drawn from memory that sketches out the main structure and layout of a village or comparable environment, produced by its former inhabitant as part of the process of delivering testimony. Abu Yasser spent over two decades meeting with survivors of the al-Dawayima massacres, creating and collecting many such ‘memory maps’ of the village based on their recollections.

Like any cartographic image that relies on a person’s perspective and recollection of traumatic events, memory maps are often imprecise and inconsistent in the specific landmarks and abstract sites they highlight in a village based on the individual’s experience of that space. At the same time, memory maps also surface as an invaluable resource for understanding how a particular space was felt and experienced by its inhabitants. For instance, a memory map may not necessarily identify all of the roads of a particular village, but might instead emphasize its main roads or the routes most commonly taken by its inhabitants. From a methodological perspective, in trying to piece together both the structure and infrastructure of a destroyed village, a memory map, though visually limited compared to a standard map, can nevertheless often better communicate how that village was lived in and, by extension, how it existed at a particular moment in time.

In the case of al-Dawayima, by putting Abu Yasser’s memory maps in conversation with the archival and testimonial materials we gathered, we have located for the first time the possible sites of Tur al-Zagh, and the likely sites of the kiln (latoun) that served as a mass grave for the bodies of those Palestinian residents killed by Israeli soldiers.

Patchwork landscape

Abu Yasser’s ‘memory maps’ capture the village as it once was, providing intimate details that guided the direction of our investigation.

By cross-referencing these maps with aerial photographs taken by the British Mandate Royal Air Force in 1945, we were able to gradually piece together the social and physical fabric of al-Dawayima, locating the village’s central square, its school, roads and wells, the revered local shrine known as the Salama shrine, the al-Zawiya mosque, the old mill, al-Jroun’s threshing floor where the Friday market once thrived, and the homes of both the former and new Mukhtar.

By analysing shadows in the aerial photographs, we could estimate the height of village structures, which in turn allowed us to position each survivor’s testimony within the reconstructed landscape.

Locating Tur al-Zagh

Tur al-Zagh, named after the ‘al-Zagh’ crow (or jackbird) native to the area, was a key site in survivors’ memories of the 1948 attack.

The precise location of Tur al-Zagh has been lost to memory. As a farming community, nomenclature for sites of importance in al-Dawayima were based on the topography of the village and its surrounding landscape. Some witnesses have referred to the location of one of the major massacres as ‘Erak’ al-Zagh, meaning a fertile and well-watered area, but most witnesses and documents refer to the site of this massacre as ‘Tur’ al-Zagh: a cave located by a hill.

As our investigation took shape, it became clear that the cave was a persistent point of reference across the testimonies of survivors, and a point of connection by which individual accounts might be woven together.

Abu Bassam was ten years old when the invasion took place and was a direct witness to the massacre at Tur al-Zagh. Fearing for their lives, three generations of his family fled their home, first seeking shelter along a nearby mountain called Qanan Abed before fleeing onward in the direction of Tur Al-Zagh.

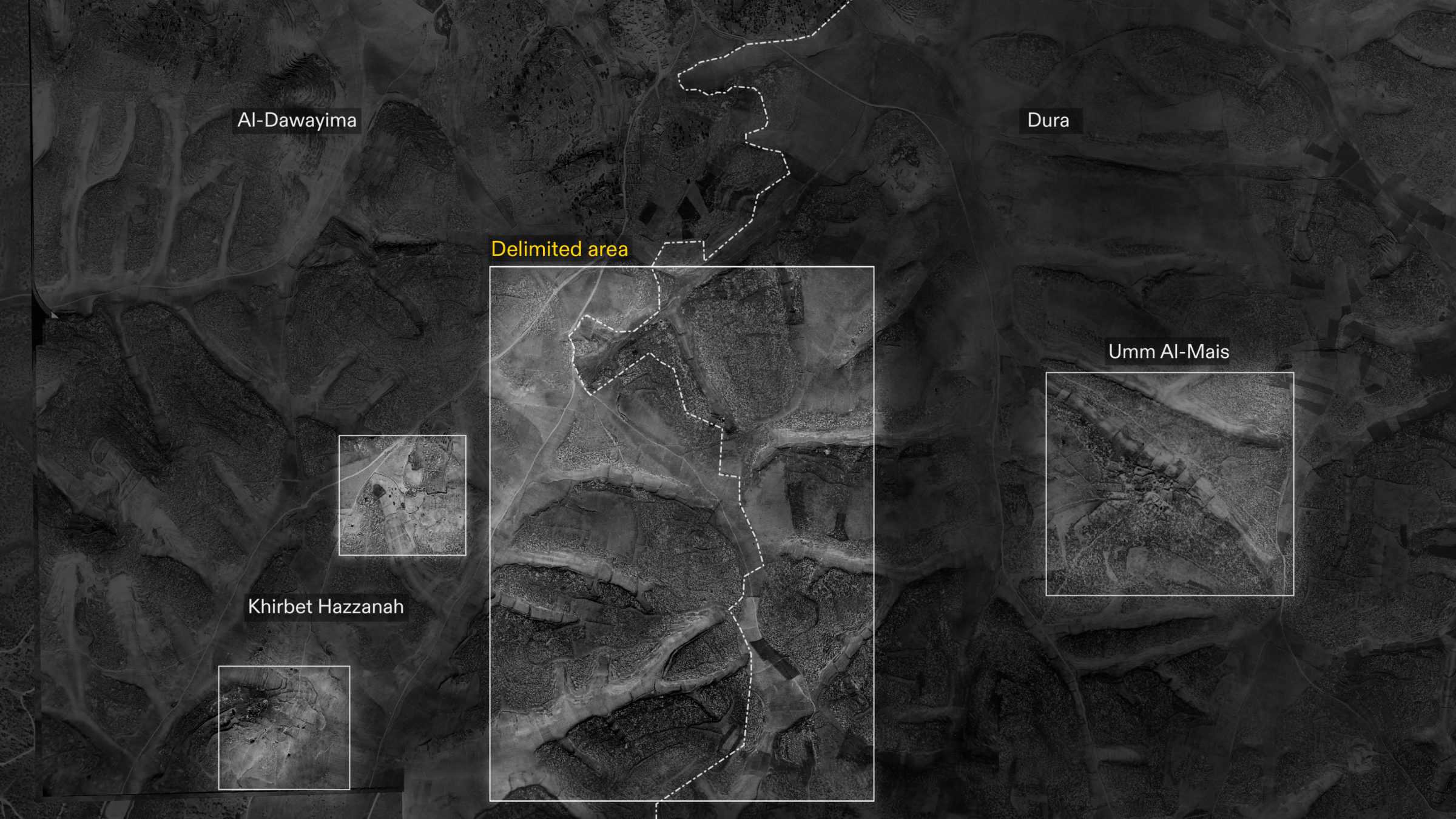

We used our 3D model of the village as a mnemonic device to help survivors retrace their steps. Referring to our model and a series of personal sketches, Abu Bassam was able to identify various markers to help us situate Tur al-Zagh. These markers allowed us to delimit the area to the south-east of the village, while understanding the trajectory of his journey from Qanan Abed helped us further narrow down the possible site of Tur al-Zagh within this area.

Abu Bassam also corroborated the testimonies of other Palestinian witnesses, who asserted that there was an old latoun—a pit or kiln—nearby, where the bodies of those killed were taken after the massacre.

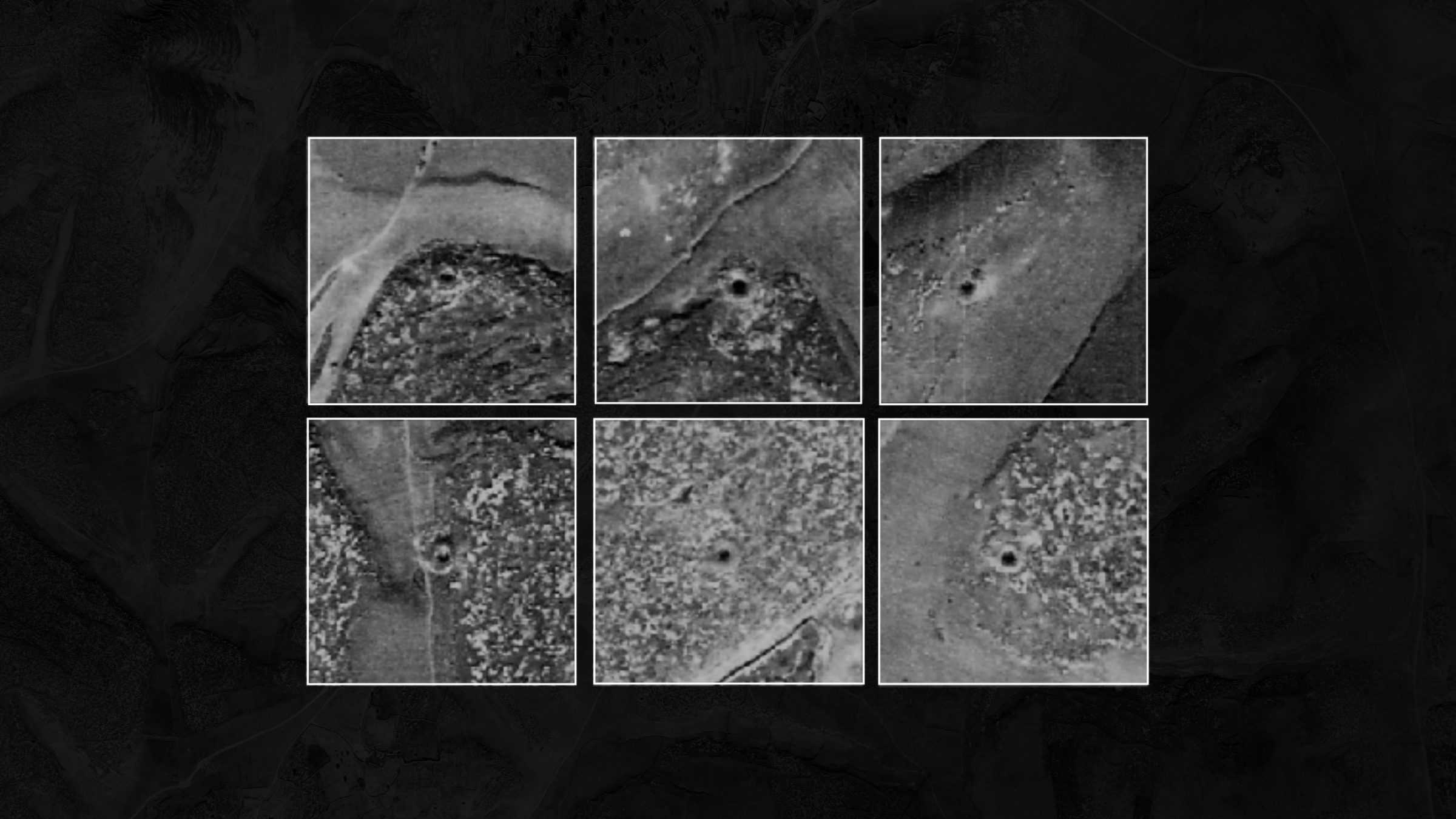

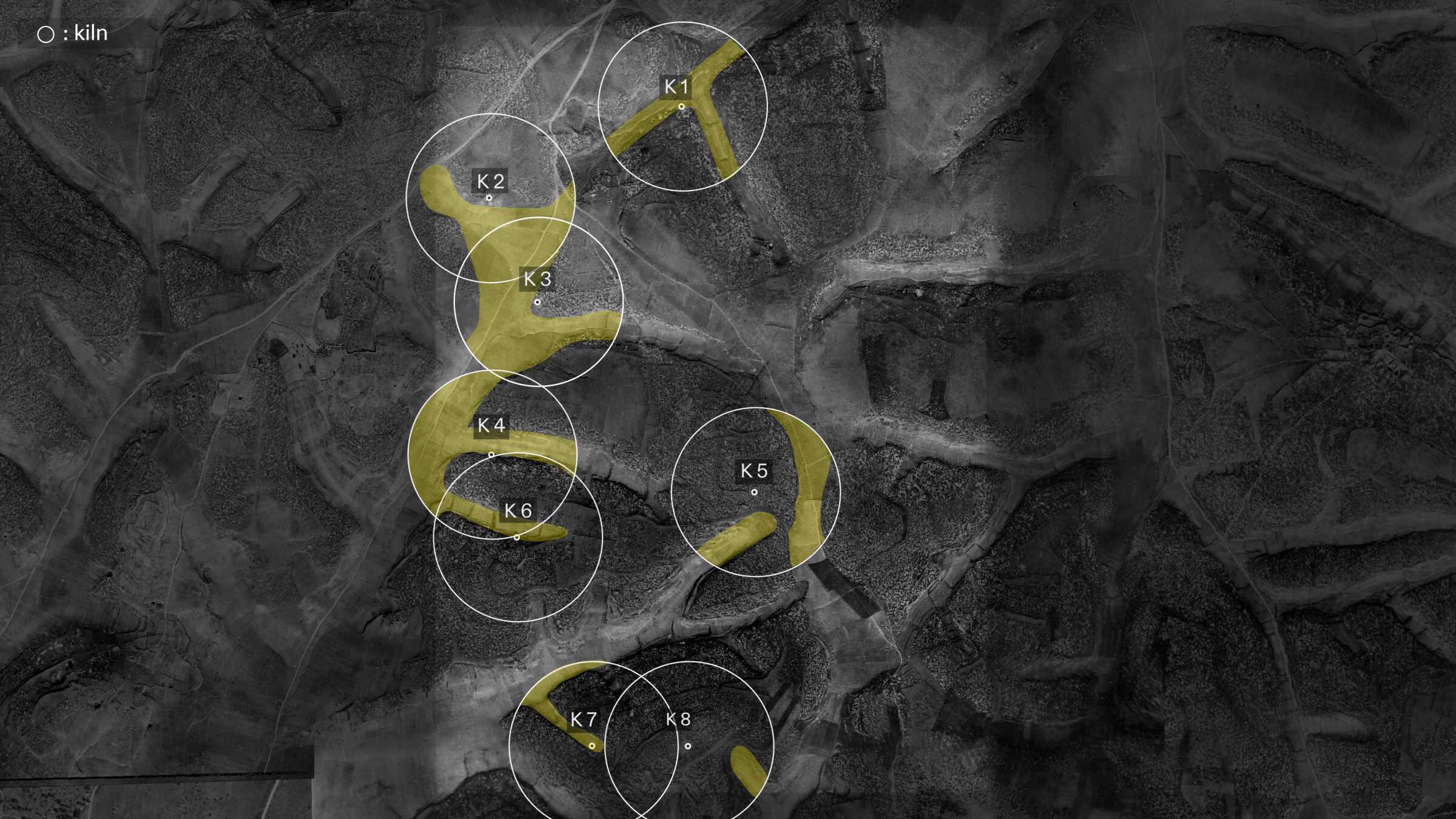

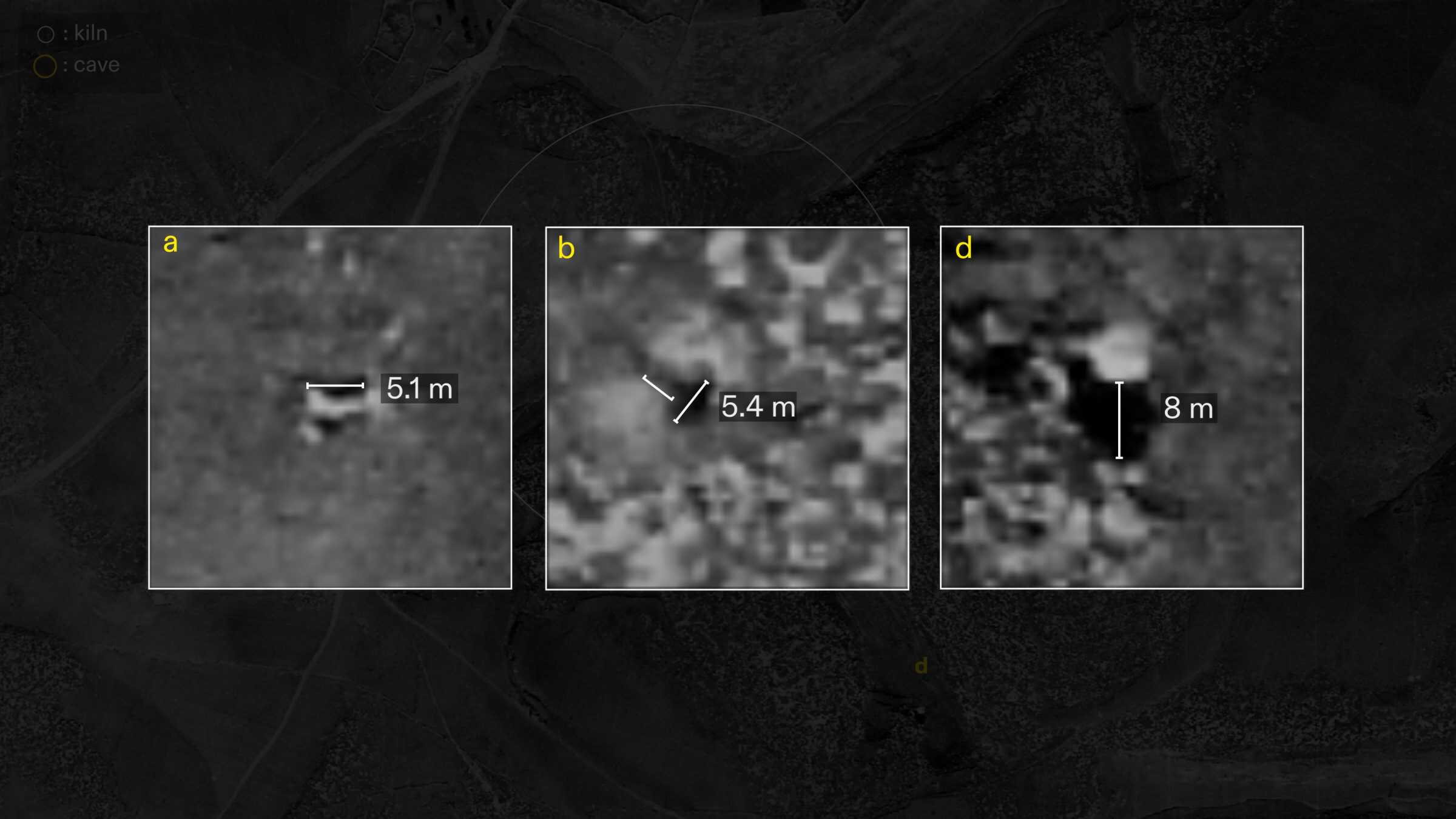

The kiln served as a key landmark. Viewed from above, lime kilns have a consistent visual signature. A British Mandate map from 1938 gives the location of various kilns in the areas surrounding the village, which then allowed us to identify them in an aerial photograph from 1945.

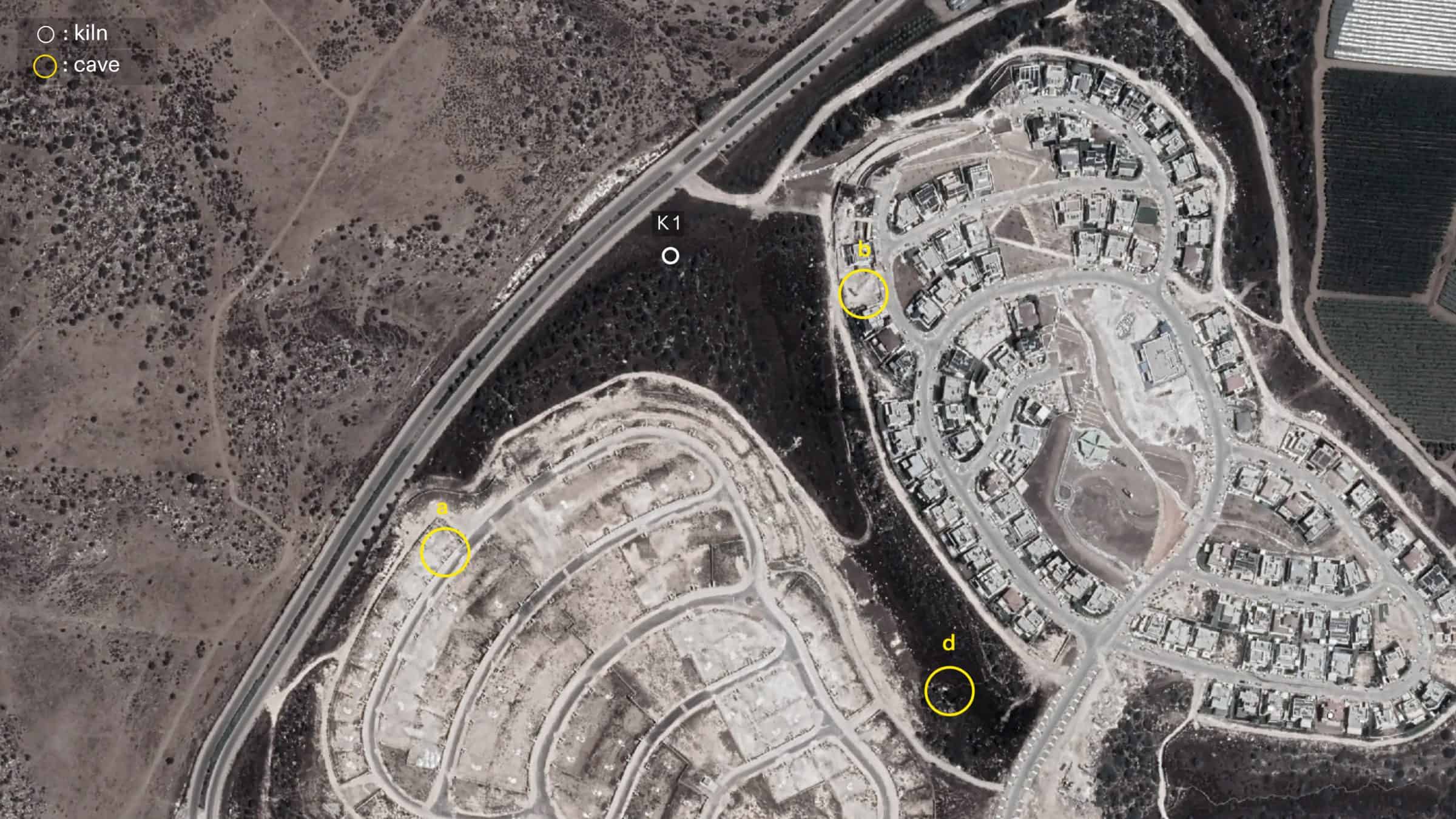

Within the delimited area established, we located eight kilns. Given that many testimonies suggested there was a lime kiln near the site of the massacre, we searched for the cave in the area around the lime kilns identified.

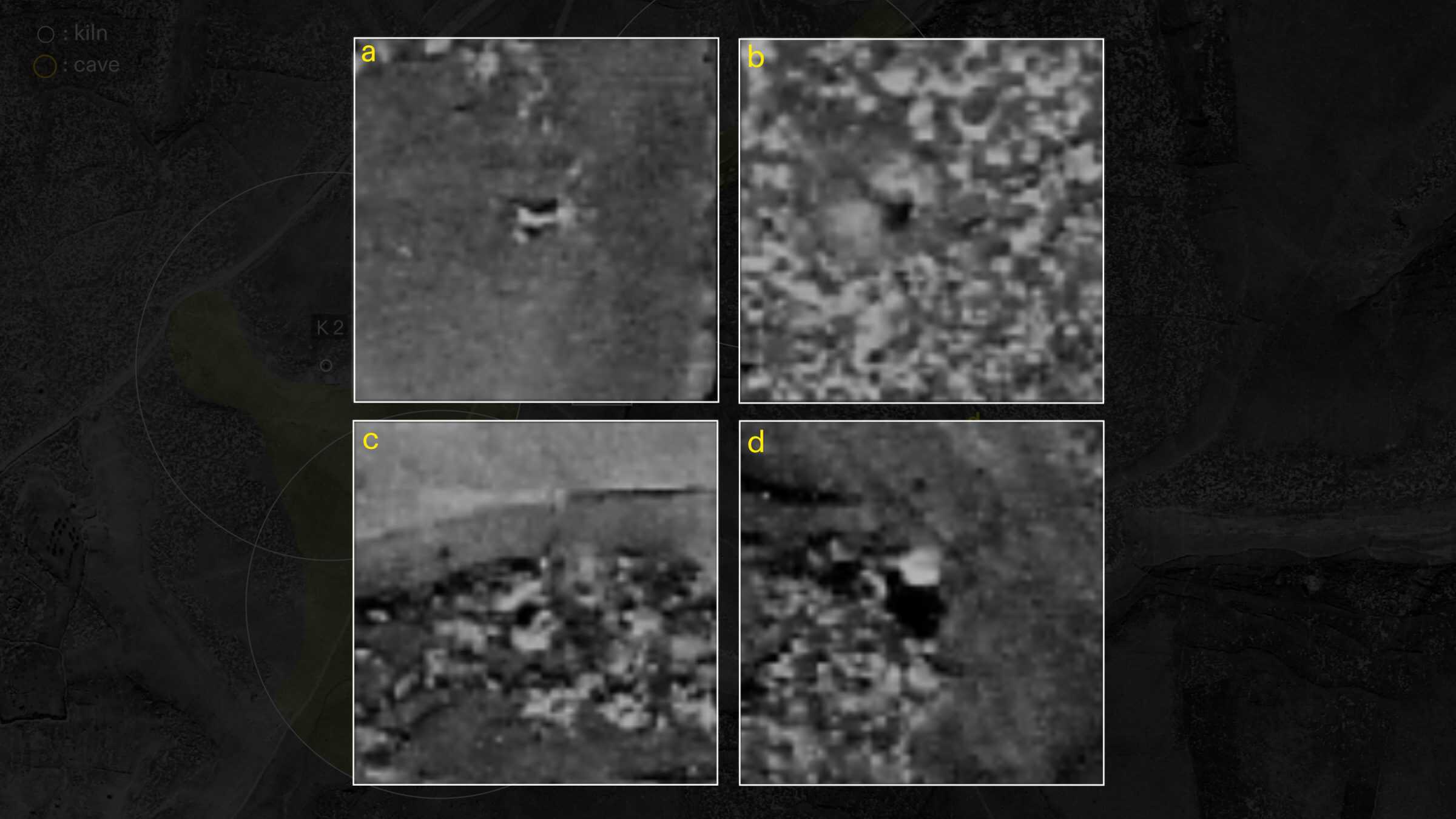

Near kilns 1, 2, and 3 we found the likely visual signatures of four caves: A, B, C, and D.

Importantly, Abu Bassam also described to us that from Tur al-Zagh, they could see the area of the house of the old Mukhtar. Drawing on this observation, we used our 3D model to corroborate these four caves as the potential locations of Tur al-Zagh.

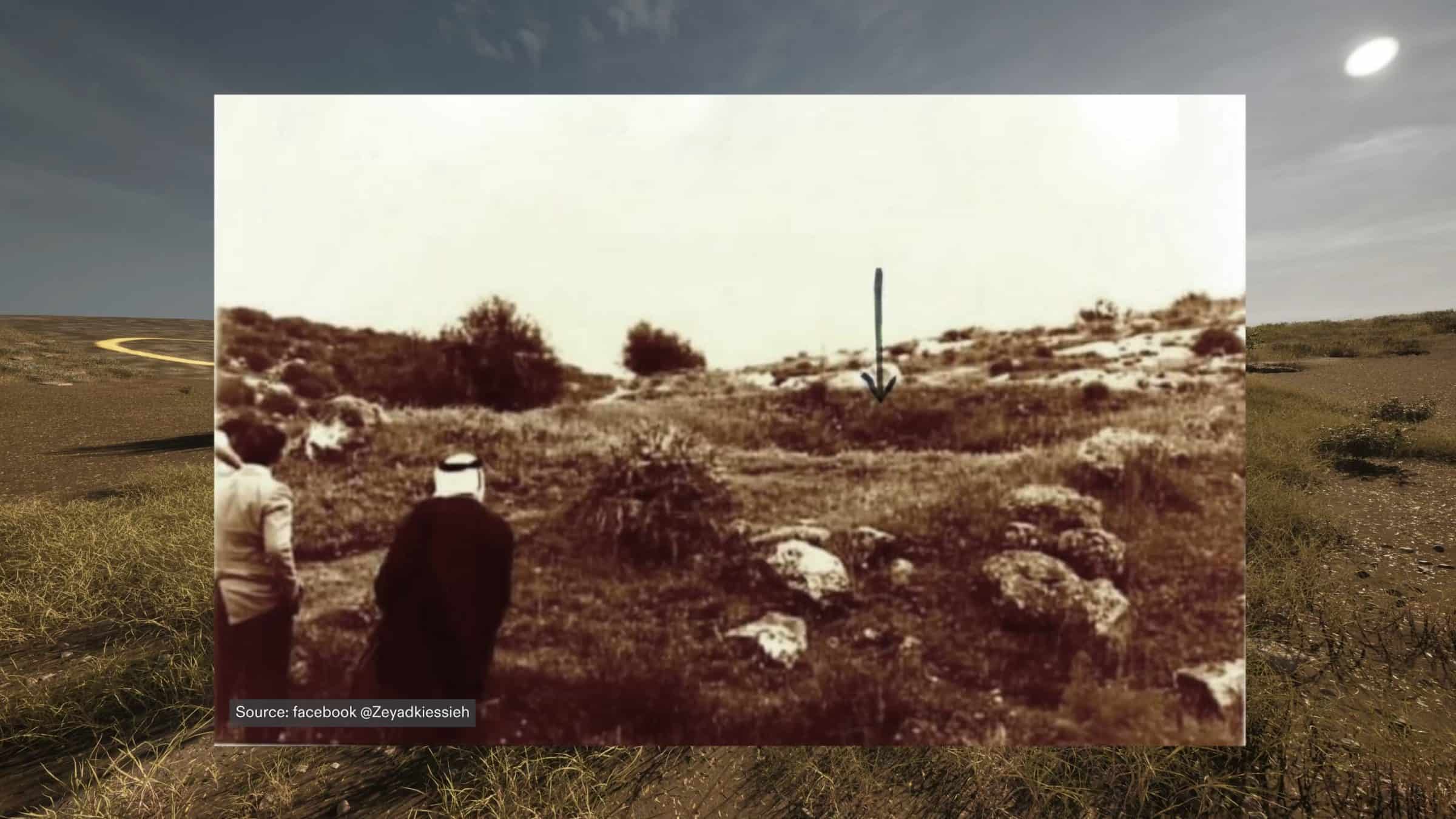

Finally, one additional piece of data allowed us to narrow down the potential sites: we obtained a 1984 photo of a kiln which was identified by the new Mukhtar of al-Dawayima in a 1984 interview to an Israeli journalist for the newspaper Hadashot as the site where the bodies were buried.

When photo-matched within our 3D model, this image only corresponds to the location of Kiln 1, suggesting that this kiln is most likely to be the site where the bodies were buried, and that therefore one of these three caves—Caves A, B and D, which are closest to Kiln 1—is the most likely site of the massacre.

Reconstructing Tur al-Zagh

Survivor accounts of the number of residents killed vary from approximately 50 to 100, including men, women and children. Based on Abu Bassam’s childhood memories of the cave, we modeled Tur al-Zagh in 3D in order to better understand its size and the potential scale of the massacre.

He described to us a cave with an entrance five metres wide, and four or five steps leading downward into a space ten metres wide and 3 metres high.

Our reconstruction suggests that the cave’s dimensions, as described by Abu Bassam, could hold between 80 and 100 people.

We also compared these specifications to our three potential caves, and both Cave A and B match these dimensions. Additionally, the visual signature of Cave B from the aerial images suggests the presence of steps leading into the cave, making it a more likely site of the massacre.

References

1Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004: 298, footnote 629.

2Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004: 488.

3According to testimony of former Palmach soldier, Zvi Steklov, collected by Zochrot in 2013, Israeli forces blew up the al-Dawayima village mosque with the aim of looting and retrieving its minaret after its forced depopulation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EeC8LSJHNhM