Methodologies

Forums

Exhibitions

This investigation was launched on 14 May 2025 in collaboration with the Palestine Film Festival, with a screening followed by a conversation between Salman Abu Sitta and Eyal Weizman. Watch the conversation:

In the weeks leading up to the termination of the British Mandate in Palestine on 15 May 1948, the Zionist paramilitary militia known as the Haganah attacked and occupied Palestinian villages across the western Naqab desert, expelling the villages’ inhabitants.

Many of those inhabitants became refugees in their own lands, seeking refuge in the Gaza Strip. Thereafter, Israel began to establish Jewish agrarian settlements, surrounding the Strip and the 200,000 refugees living there. All traces of Palestinian inhabitation in the ‘envelope’ around Gaza were destroyed, and Palestinians continued to be denied the right to return to their lands.

Much of the infrastructure put in place following the 1948 Nakba – roads, barriers, and buffer zones – are still legible in the system of ‘spatial control’ imposed on Gaza during the genocide that began in 2023.

On the night of 13-14 May 1948, mere hours before the declaration of the formation of the State of Israel, the village of al-Ma’in (also known as Ma’in Abu Sitta, or the Abu Sitta Spring), was occupied by the Haganah, the main Zionist paramilitary organisation that operated in the British Mandate for Palestine. The population of the village was subsequently expelled, and most buildings were destroyed.

Located on a shallow hill overlooking Khan Younis and the southern Gaza coastline, al-Ma’in was at that time home to the Abu Sitta family, Bedouin Palestinians affiliated to the Tarabin tribe which at that time inhabited the area linking Gaza and northern Sinai. Al-Ma’in was the birthplace of Salman Abu Sitta (b. 1937), the foremost chronicler of the ongoing Nakba and an advocate for the Palestinian right of return. From his home in Kuwait, and from the offices of the Palestine Land Society in Beirut and London, Salman has dedicated his life to compiling a comprehensive Atlas of Palestine. His research on the history of his hometown was published in his memoir Mapping my Return.

FA had previously worked with Salman to locate a mass grave in the Palestinian village of al-Dawayima, on the western slopes of the Hebron Mountains. For this investigation, Salman and FA researchers digitally reconstructed the village of al-Ma’in and the events of 13-14 May 1948 within an immersive 3D environment, using our bespoke interviewing technique of ‘situated testimony’.

The collaborative process of modelling and reconstruction sought to bring together Salman’s memories and knowledge with satellite imagery and other archival material, as well as aerial images taken by the Israeli air force in the decade after the village’s occupation, to better understand the history of the settlements built over his family’s land after their displacement.

‘I want to know more about the people who took my land, who are they? Why did they dig and scrape the seven roads, how did they build their landscape on our ruins? Why did they build new roads different from ours? How did they select the location of the new kibbutz? What are the first installations they made?’ — Salman Abu Sitta

Al-Ma’in in 1945

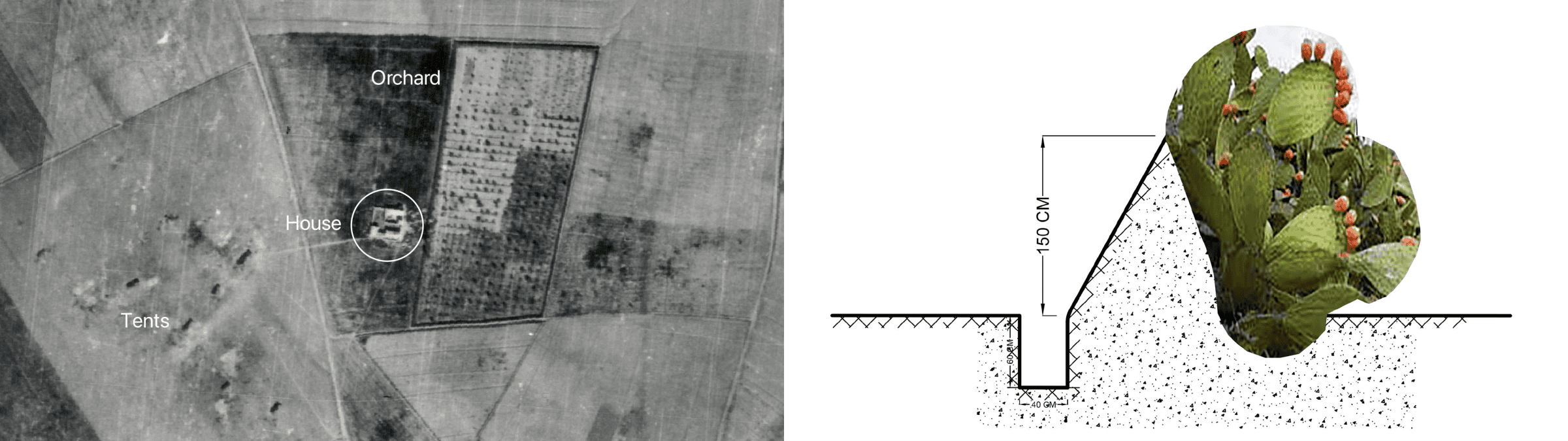

The first time al-Ma’in was photographed from the sky was on 28 January 1945, during a Royal Air Force (RAF) aerial survey of Palestine. Aerial photographs offer an incomplete picture of a landscape: on an aerial image of an agrarian landscape, a blurry darker spot could be a pile of hay, an earth mound, or the opening of a water hole. A change in tone on the surface can be a pedestrian route or a water canal. Thanks to Salman’s expertise, and lived experience of the landscape, we were able to identify and distinguish features of the terrain captured in those aerial photographs.

The centre of al-Ma’in is east of Wadi Farha (or al Wadi Ma’in), the southernmost tributary of Wadi Gaza, a seasonal stream which flows into the Mediterranean Sea on the coast of what is today the Gaza Strip. From the centre of the village, seven routes fan out in all directions: west to Khan Younis, northwest to Deir al-Balah and Gaza, and east to Beersheba.

This crossroads was the heart of the settlement. Around it were clusters of structures including a bayarah – a deep well surrounded by an orchard of palm trees and a vegetable garden.

The Abu Sitta family was first to bring agricultural mechanisation to the area: in the late 1920s or early 1930s, Salman’s father, Sheikh Hussein Abu Sitta, and his cousin Ahmed Ibreisha Abu Sitta, bought a diesel-operated motorised water pump from Jaffa and installed it over the well, replacing the previous camel-powered operation. In the early 1940s, they installed a motorised flour mill with four silos, which FA researchers modelled based on Salman’s memory. In the 1940s, after seeing benefits from the motorised well and the mill, the family bought a tractor to help with the harvest, though they got rid of it when they realised it trimmed the stalks too high, wasting precious crops.

The family’s adoption of agricultural modernisation – including the use of concrete, tractors and diesel engines during the period of the British Mandate – contradicts the Zionist narrative that these modern practices were introduced to the area by Israeli settlers only after the Nakba.

Also in the vicinity of the crossroads were two small shops, owned by traders from Khan Younis. One was killed on 14 May 1948, when the village was occupied by the Haganah.

East of the crossroads was a school constructed by Sheikh Hussein Abu Sitta, at his expense, in the 1920s. An aerial photograph from 1945 does not yet show the second school building, constructed in 1947, just a year before the Nakba.

The nearby house of Sheikh Hussein was a walled complex with rooms around a central courtyard. The rooms included a large apartment building, storage rooms, and a cattle shed. From the house, small routes lead towards the well, the school, and a large walled orchard also bounded by a cactus fence. At the northwestern end of the orchard was a hidden passage, a long, low ditch, that led to Wadi al-Ma’in.

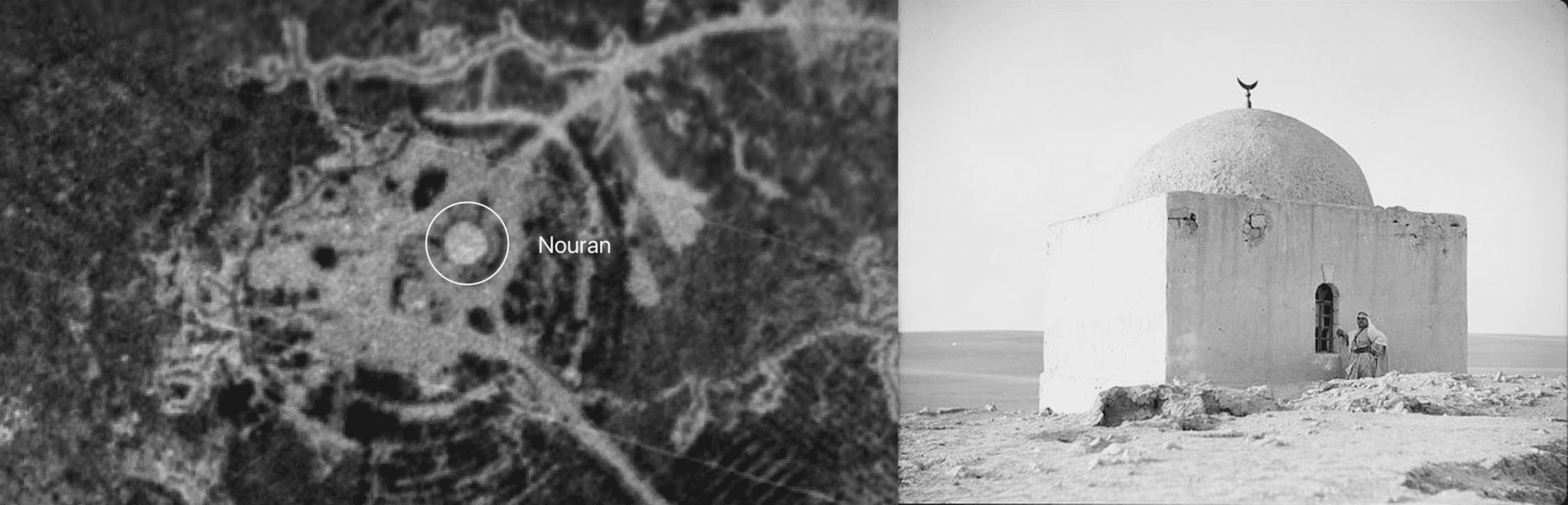

Maqam Nouran, also known as Sheikh Nouran, was a shrine built on a hilltop at the southeastern edge of al-Ma’in. It held deep cultural and spiritual significance locally; local women would visit the maqam to seek blessing, if they were trying to conceive.

Agricultural Clockwork

Cultivation around the seven main routes was arranged like clockwork. A few hundred metres from the centre of the crossroads were the stone houses or beikas, which functioned as a hub for each branch of the Abu Sitta family. Near each set of stone houses was a large rectangular orchard. These orchards were planted in the 1930s; their presence was a sign of wealth.

Further away from the centre, the fields became larger. The Abu Sitta family cultivated 60,000 dunams of land – nearly 15,000 acres – three-quarters of which were wheat and barley.

To understand the logic of agriculture in the area, FA spoke to agricultural expert Mohammed Abu Jayyab. Abu Jayyab’s family is from a village north of Gaza, and he grew up in the Gaza refugee camp of al-Maghazi on the southern banks of Wadi Gaza.

Mohammed’s familiarity with the land, the soil, and local cultivation practices enabled FA researchers to analyse the 1945 aerial images.

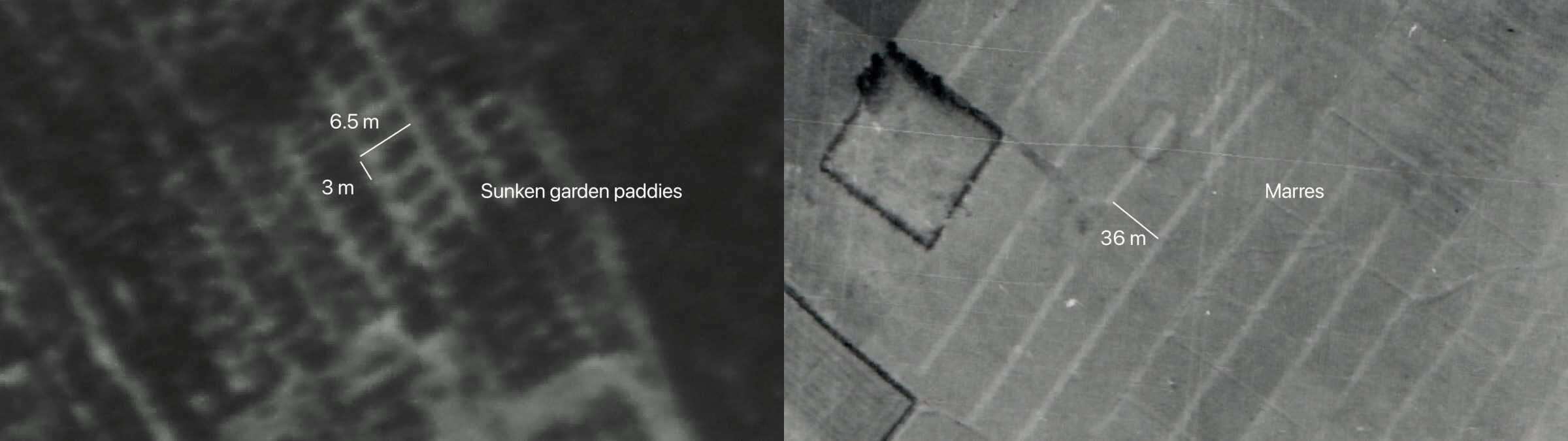

Behind the bayarah, Mohammed identified a grid of sunken gardens that functioned as vegetable beds — yet another sign of modern cultivation systems. Fields were divided into sections, roughly 40 metres wide. Mohammed estimated that at least half the fields were barley.

Al-Ma’in was on the southernmost edge of the Wadi Gaza basin, at the intersection of distinct environmental conditions suitable for growing wheat and barley. By 28 January 1945, when the RAF’s aerial images of al-Ma’in were taken, the wheat and barley would have grown to about a foot high, enough to form the ground cover that would render the field dark. Lighter patches were likely fields left fallow.

The Destruction of al-Ma’in

The village of al-Ma’in was known for its revolutionary spirit as much as its strategic significance. Salman’s father, brothers, and cousin were famous leaders of Arab resistance to Zionist colonisation. His cousin, Abdullah Abu Sitta led a revolt against British rule between 1936 and 1939 in the Beersheba district, and coordinated with the Muslim Brotherhood on the defence of the area from 1947, until the Egyptian Army entered Palestine on 15 May 1948. After the Nakba, he formed part of the Fedayeen resistance in Gaza.

The settlers and Zionist militias in the areas called al Ma’in the ‘outpost’ and referred to its inhabitants as a ‘gang’. A Haganah soldier named Arye Aharoni recalled the excitement upon receiving orders to attack al-Ma’in:

‘Who in the battalion did not speak of it? This is the seat of Abdallah Abu Sitta, the organiser of the Negev gangs; the man whose reputation spread fear around him, that every Bedouin person has respect and awe to.’

On 13 May 1948, around 10pm, the Zionist militia approached ‘Khirbet Ma’in’, riding off-road vehicles onto which they had welded armoured plates. (The British and the Zionists referred to many Palestinian villages as khirbet, or ‘ruins’; they assumed that their inhabitants had not built the structures there, but rather settled around ancient ruins).

‘On the near horizon’, Salman writes in his memoirs, ‘we saw the headlights of twenty-four armoured vehicles approaching us. A monster with forty-eight eyes faced us, with the ominous roar of its engines’. The Haganah attacked at dawn on 14 May. Coming from the east, they first encountered the school. From the school’s rooftop, villagers fought to defend their land. There were between ten and fifteen local riflemen in al-Ma’in, armed mostly with World War I-era rifles. They were soon overwhelmed.

At the northeast corner of Salman’s father’s orchard, there was a gap in the cactus fence through which ran a ditch created by rain. It led to the beginning of the al-Ma’in Wadi. Understanding that the village was lost, many residents escaped into the Wadi.

‘Women and children ran in a northerly direction. Mothers tried to locate their children in the darkness. They tried hurriedly to pick up things their children needed: milk, blankets, and the like. In the background, the threatening lights, the hail of bullets tracing arcs in the sky, the hurried confusion, the agonising cries, and the shouts for a missing child heightened our fear of impending death. My mother led my sister and me in the darkness.’ — Salman Abu Sitta

Salman recounted his flight through the Wadi as FA researchers modelled what he was describing. As he looked back on al-Ma’in, he recalled seeing pillars of smoke on the horizon. An Israeli soldier described what they found in al-Ma’in:

‘We went to Abu Sitta’s house and were struck: in the heart of the desert, unbelievable richness: fancy furnishing, an abundance of oriental and European clothes, radio, a truck, a decorated silver Bedouin sword, a large and significant archive of documents and photographs, letters from the Emir Abdallah and Hassan Bana, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt; a lawyer certificate of one of the family members, Shakespear’s Othello in original version, near the Quran. The excitement knew no bounds when we found the weapon storage. W-e-a-p-o-n-s… We were delighted.’

The White Horse

The first military-agrarian kibbutz built over the lands of Al-Ma’in was called Nirim, which means ‘ploughed fields’ in Hebrew. The Nirim kibbutz group had previously settled in an area near the border with Egypt, but in April 1949, they sought a new location within the vast tracts of land that had become available following the expulsion of the indigenous Palestinian population. That month, they decided to settle where fields of wheat and barley had been planted by the former inhabitants of the area, shortly before they were expelled. These were the fields of Ma’in Abu Sitta.

There was one building left standing a few hundred metres south of the central crossroads of al-Ma’in – a concrete structure which the settlers called the ‘White House’. Around the structure, the settlers pitched their tents and a few prefabricated huts. They harvested the Abu Sittas’ fields. The group were trained, and armed, and would shoot at any Palestinians that crossed the ceasefire line to the west.

The settlers stayed in the ‘White House’ for nine months, as the beginnings of a permanent settlement were constructed nearby; by January 1950, they had moved into the new kibbutz Nirim. It was located 3km north of the ‘White House’, at the top of a sandstone hill, an area of fields belonging to Salman’s father.

Before and After

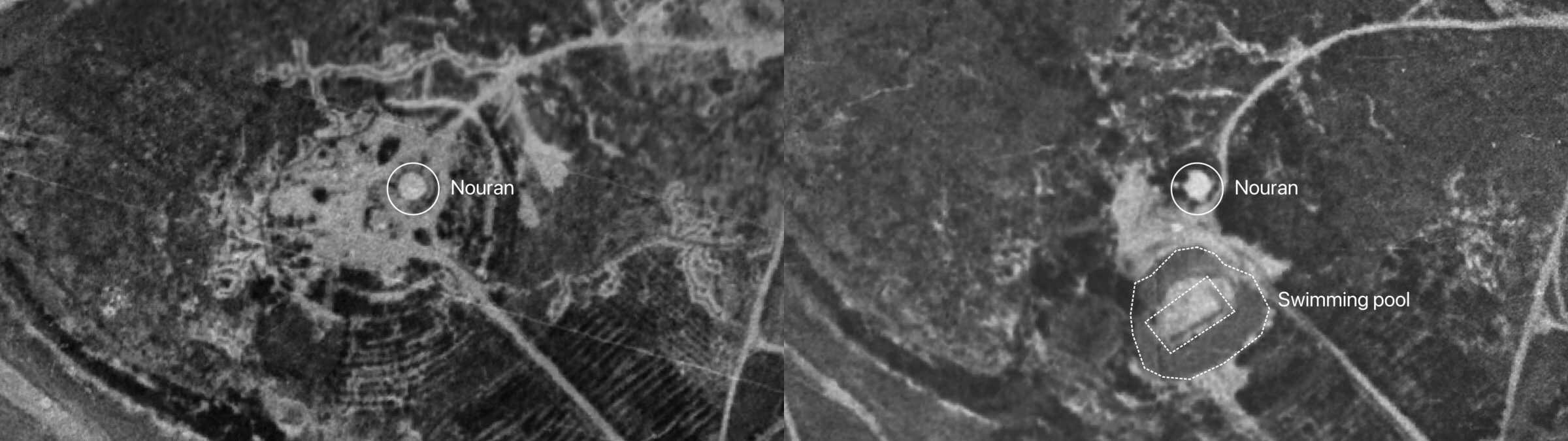

Comparisons between aerial images taken by the RAF in 1945, and by the Israeli air force in 1956, provide a new perspective on the erasure of the village of Ma’in Abu Sitta. Over those nine years, the entire landscape had been transformed. Only Wadi al-Ma’in connects the two images. The central crossroads was gone, though a few of its routes remained. New roads crossed the landscape, along which four new Kibbutz settlements were located.

In the 1956 image, the Abu Sittas’ well is visible, though the grass around it has grown high, testifying to its lack of use. The building around the well, the engine, and the silos are gone. The large courtyard house of Salman’s uncle, Ibreisha Abu Sitta, is visible only as a ruin.

Later aerial images, from the 1950s to the 1970s, reveal the ongoing process of consolidation of the kibbutz infrastructure.

Photographs of Nirim from the 1950s show that the first elements to be built were fortifications, and only when the perimeter was secured were the ‘softer’ functions of the settlement put in place.

At the bottom of each of the guard towers is a trench that proceeds through to the residential areas, and from there into the interior of the settlement, where the infirmary, secretariat, dining hall, washrooms, nursery, and other buildings were located.

The rear flank of the kibbutz are the farm buildings, the industrial zone, the steel workshop, and the car garage. The settlements built on Abu Sitta’s lands were fortified frontier settlements, part of a ‘living wall’ Israel constructed to surround Gaza, blurring the distinction between the civilian and security functions of these frontier settlements.

This blurring would later prove lethal; four of the settlements built on Abu Sitta lands were attacked on 7 October 2023.

The 2023 Genocide

Since October 2023, the Israeli army took over the site of the White House, and a nearby military base served as a point of departure for raids into Khan Younis and its surroundings.

FA’s research since October 2023 has revealed more than a dozen similar ‘raid routes’ into Gaza, which the Israeli military has used during its genocidal military campaign.

As in al-Ma’in, many of these routes follow paths originally walked by the indigenous Palestinian communities of the region.