Commissioned By

Additional Funding

Collaborators

- Working Group Four Faces of Omarska

- ScanLAB Projects

- Grupa Spomenik

Methodologies

Forums

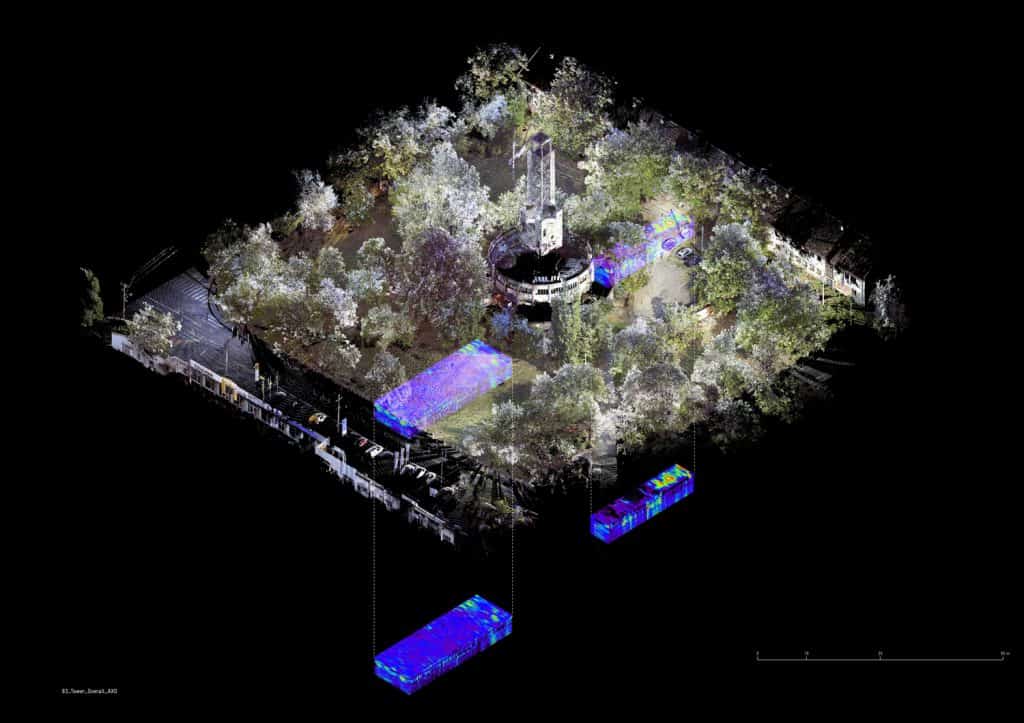

Staro Sajmište (‘the Old Fairgrounds’), on the outskirts of Belgrade, was inaugurated in 1938 as the site of an international exhibition. A series of pavilions, each representing a state or company, was built around a central tower.

At the end of 1941, following the Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia, the fairgrounds reopened as the Semlin concentration camp. Jews and Roma were systematically murdered at the site, many by the first use of vehicle-mounted gas chambers, known as Gaswagen. The camp also held communists and resistance fighters.

The logic of visibility that had dictated the initial layout of the exhibition site was well-suited to the panoptic requirements of the concentration camp. In fact, no major structural transformation was necessary, except for a high fence that was erected around the compound.

Over several generations following the war, the complex became artists’ studios and workshops. The fence was taken down. Some of the abandoned structures were occupied by a Roma community that included survivors of Nazi persecution and their descendants.

Years later, it was proposed that the site be transformed again, into a Holocaust memorial centre and museum. As a candidate country for admission to the EU, Serbia is required to support ‘the adequate commemoration of the Holocaust sites on its territory’. The transformation would turn the site back into a site of exhibition, and the fence would be erected once more—this time, to protect the museum.

These plans, however, required the displacement of the site’s inhabitants, including the Roma communities who were themselves victims of the Nazis. The first evictions began in the summer of 2013.

It is an unacceptable contradiction that a Holocaust memorial should be built on forcefully-cleared ground. In partnership with ScanLab, Grupa Spomenik and the forensic archaeologist Caroline Sturdy Colls, Forensic Architecture (FA) conducted surveys of the site both above and below ground, in an attempt to protect the existing homes, and in the belief that commemoration should not necessarily contradict ongoing inhabitation.

On 5 October 2013, we convened a public forum inside one of Staro Sajmište’s most infamous structures—the former German pavilion, which had served as accommodation for the camp’s inmates during World War II.

There, we publicly presented our archaeological report, leading a discussion about the future of the site.

Methodology

Methodology

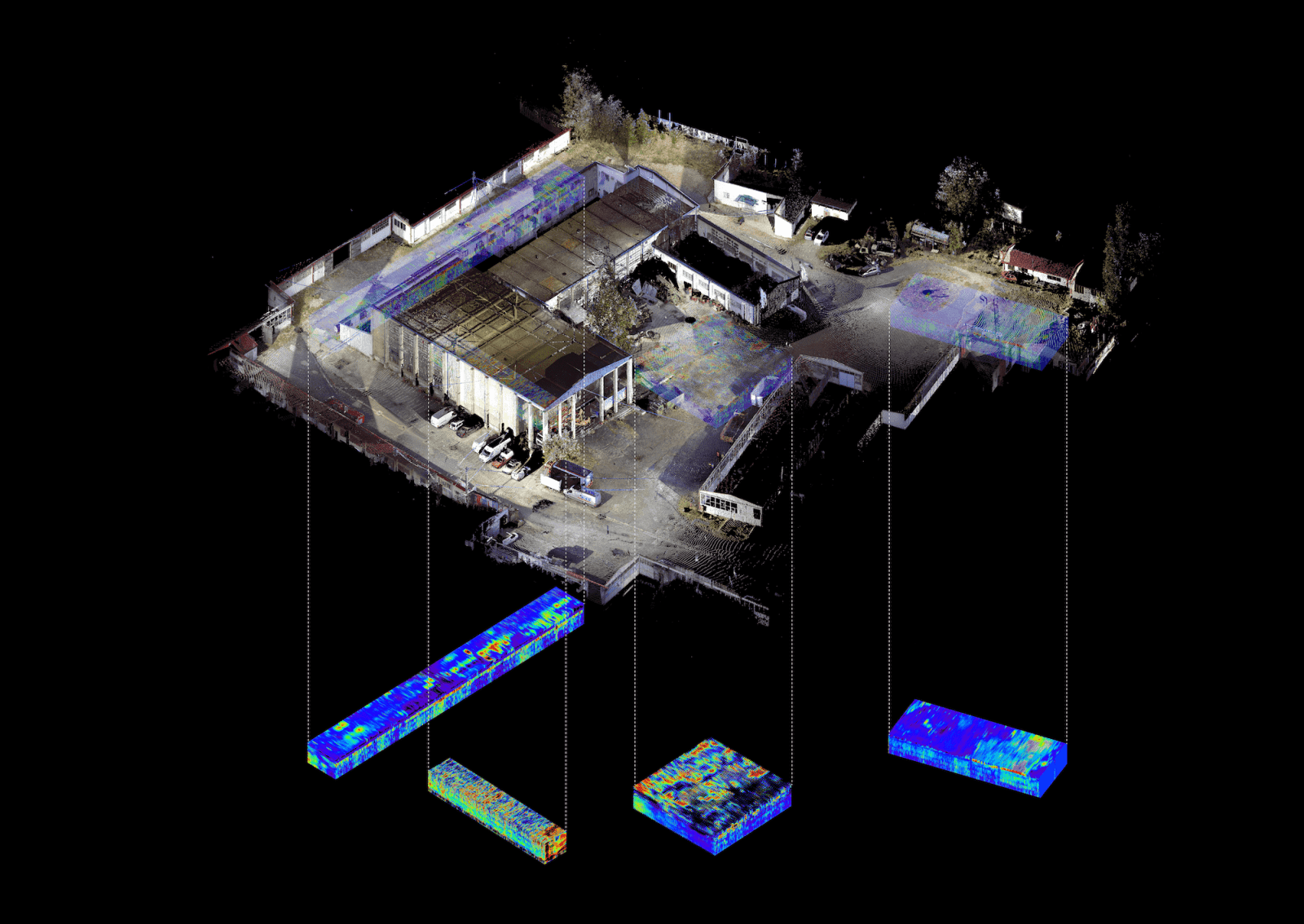

In the spring of 2012, FA collaborated with forensic archaeologist Caroline Sturdy Colls and the Belgrade-based Monument Group in undertaking a study of the remnants of the site, above and below ground.

Sturdy Colls had previously developed a method of ‘non-invasive’ archaeology involving the use of remote sensing and ground- penetrating radar (GPR), an instrument that transmits pulses into the ground to a depth of up to 15m to detect minute differences in densities. In the fuzzy 3D model of the subsoil produced by this technique, one can identify irregularities in soil structure that indicate buried objects, as well as voids.

Subterranean objects do not have sharp, clear borders, however—they are made visible only as a gradual increase in the density of the medium of the earth, and a result their identification often depends on probabilities and interpretation. Objects can only be confirmed once they have been excavated and cleaned of extraneous debris; their borders are reestablished, but much information is lost, contrary to the aim of the study.

FA also worked with London-based laser-scanning practice ScanLAB, who recorded the architecture aboveground. ScanLAB’s work produces measurable photographic spaces which can be navigated as a digital 3D environment.

The combination of aboveground and underground scanning resulted in an archaeological report that presented the site as a process of ongoing transformations, additions, and alterations.