Date of Incident

Location

Publication Date

Methodologies

Forums

This is an ongoing project. Share your footage with us here.

Our data is public; we’ve only redacted video evidence that is not already widely shared. View the data here.

The ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests that have swept the US since May 2020, in the wake of the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black Americans, constitute one of the largest uprisings against systemic racism in policing in the US in a generation.

But this popular movement has itself been met with widespread and egregious police brutality. And more than ever before, evidence of that violence has been captured in videos and images.

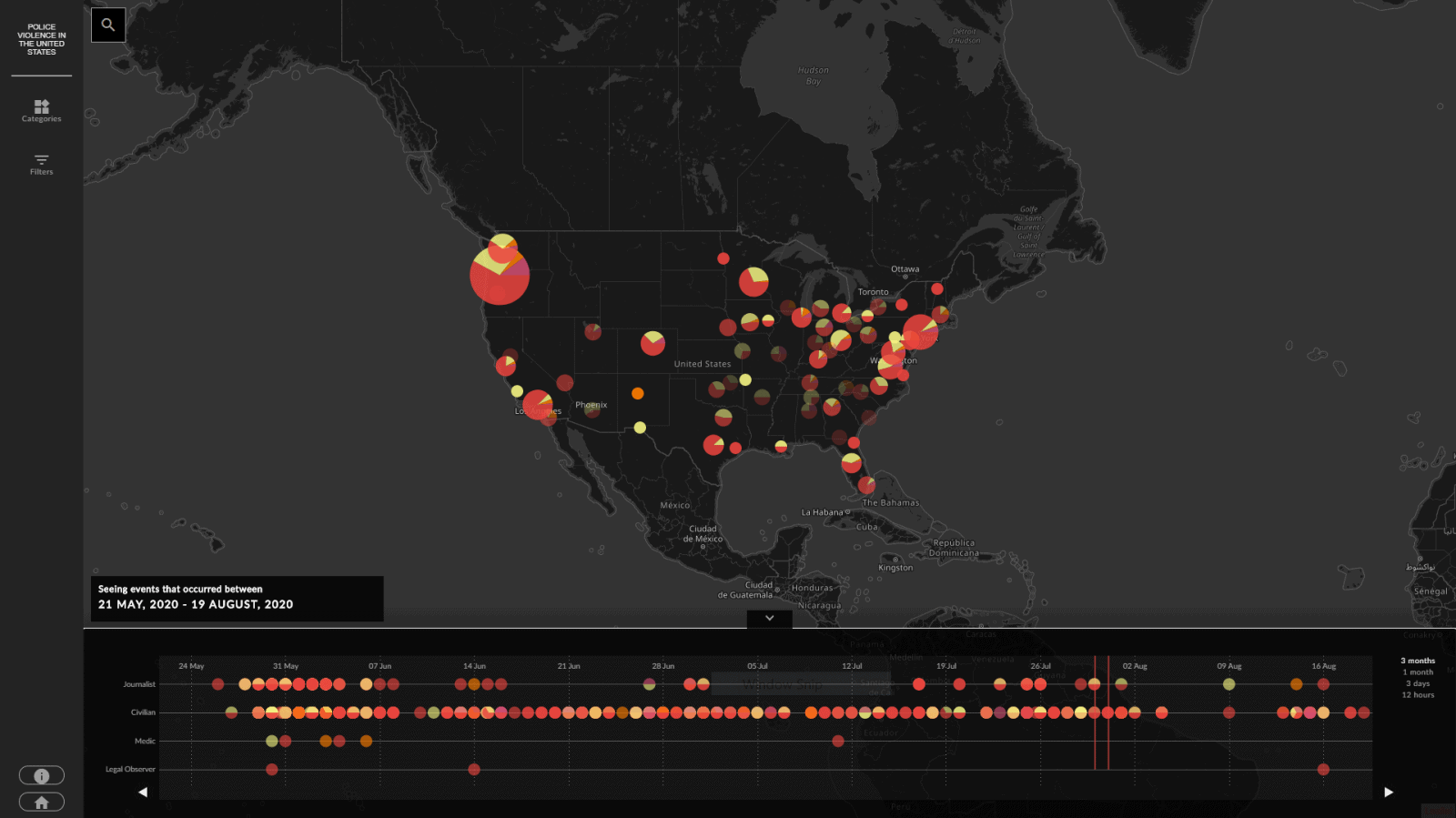

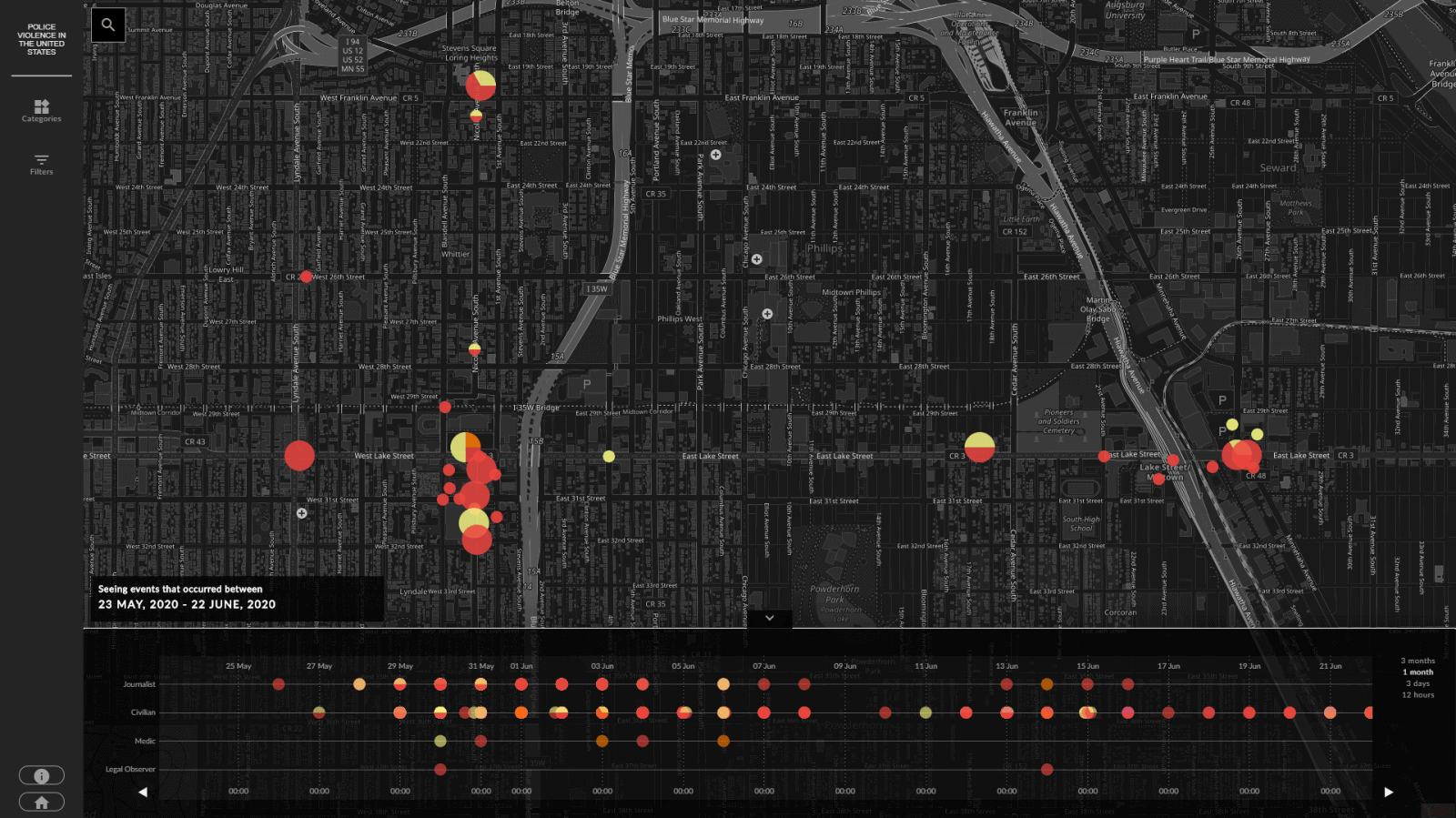

Together with Bellingcat, FA has geolocated and verified over a thousand incidents of police violence, analysed them according to multiple categories, and presented the resulting data in an interactive cartographic platform.

Out of the data emerges a picture of officers and departments engaging in widespread and systemic violence toward civilian protesters, journalists, medics, and legal observers.

That violence has entailed continuous and grievous breaches of codes of conduct, the dangerous use of so-called ‘less-lethal’ munitions, reckless deployment of toxic chemical agents, and persistent disregard for constitutional and humanitarian norms.

The data reveals patterns and trends across months of violence, including the use of tactics such as ‘kettling’, and interactions between officers and members of far-right hate groups and militias.

This research is already supporting prospective legal action, independent monitoring, reporting, and advocacy, as well as movement demands for accountability and abolition.

Update

01.12.2020

01.12.2020

Researcher Imani Jacqueline Brown presents our findings to a session hosted by the UN’s Working Group of Experts on Peoples of African Descent (WGEPAD), part of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Watch her presentation here (from 5m40). Read her statement, with references, here.

Methodology

Methodology

We consider a video or image to be within the scope of the archive if it directly depicts or, in certain cases, otherwise evidence violence or serious misconduct by law enforcement agents. The data is according to certain behaviours identifiable in those videos, including (but not limited to):

– The use of kinetic impact projectiles

– Arrests and intimidating behaviour by officers

– Apparent ‘double standards’ in the way that officers behaved toward white and black protesters, including interactions between officers and members of far-right hate groups

– Policing tactics such as ‘kettling’, which subject civilians to risk of harm, or prevent civilians from complying with curfews or other instructions

– Destruction or confiscation of property by officers

We geolocated images and videos based on visual clues within the frame, and contextual clues from open sources, and determined the incident date by referencing corroborating information from open sources. Then we looked for trends and themes in the data, connecting out to other open source data such as hundreds of curfew orders issued throughout May and June 2020.

Re-sharing and amplifying video material from protest contexts can have a range of positive and negative consequences for the authors and subjects of that material. Our experience, as well as discussions with a range of stakeholders, has also taught us that there is no single ‘best practice’ when it comes to handling and sharing open source image data in light of that densely overlapping network of concerns, benefits, and potential consequences.

In order to take a cautious approach toward those consequences, and mitigate any potential risk, we present the data through text-based descriptions and tags, and only provide the source URL for a datapoint when it has met certain criteria, including being already been widely shared. For more about our process and ethical praxis, read a short mission statement for the project, drafted for potential partners and outreach efforts.